CHAPTER 10 Lateral Approach to Hip Arthroscopy

Introduction

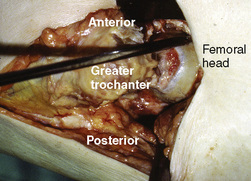

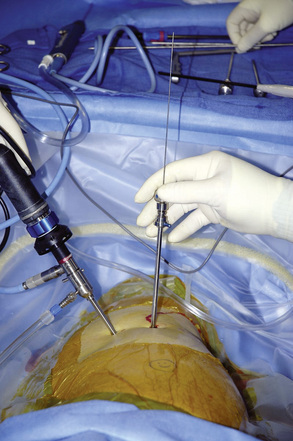

Hip arthroscopy was first performed in our practice with the use of the supine approach on a fracture table for distraction. During our early experiences, problems of getting into the hip joint and complications such as the scuffing of articular cartilage, poor maneuverability, and the inability to achieve the result before extensive extravasation made the procedure difficult. Specific instruments were not developed, and distraction parameters were not established. As a result, the procedure was not predictable for entering the intra-articular space that is now known as the central compartment. In 1931, Burman was the first to use an arthroscope in the hip in a cadaveric study. However, he was unable to enter the central compartment, even with distraction. Our associate James M. Glick, MD, performed 11 procedures between 1977 and 1982, and he had difficulty getting in on two occasions. Because of our experience with the lateral decubitus positioning in total hip replacements, the idea of approaching hip arthroscopy in a similar way was developed. We dissected a cadaver hip to determine the most direct access to the intra-articular space, and we then described the anterior–peritrochanteric and posterior–peritrochanteric trochanteric portals (Figure 10-1); these have subsequently been referred to as the anterolateral and posterolateral portals. In 1986, distraction was introduced by Erikkson with the use of a fracture table to facilitate entry into the central compartment. We developed a rope-and-pulley system with weights as we used for shoulder arthroscopy as our first hip distractor (Figure 10-2). The first patient in whom we performed arthroscopy with the lateral approach was a massively obese woman with hip pain in whom Dr. Glick had previously performed arthroscopy without success in the supine position. In the lateral decubitus position, the obese portions of her thigh drooped down to expose a prominent greater trochanter. The neurovascular structures are safely away from the portals, and the surgeon is very familiar with their location; these portals offer a direct shot into the femoroacetabular joint. Many of the surgeons interested in hip arthroscopy at that time adopted the technique and continue to use it today.

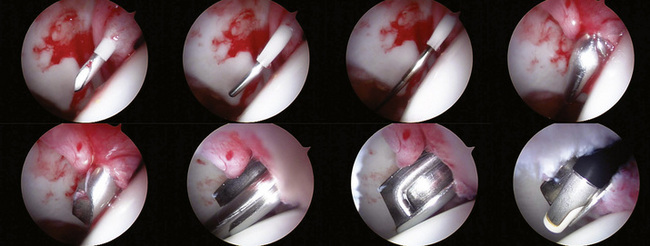

The major advancements in getting into the central compartment were a result of distraction and the use of Nitinol wire cannulated trochars (Figure 10-3). Later, the development of longer arthroscopes, slotted (half-pipe) cannulas, and curved and flexible instruments allowed for advanced techniques that have followed a similar path as those used for knee and shoulder arthroscopy.

Indications

Surgical technique

Patient Positioning

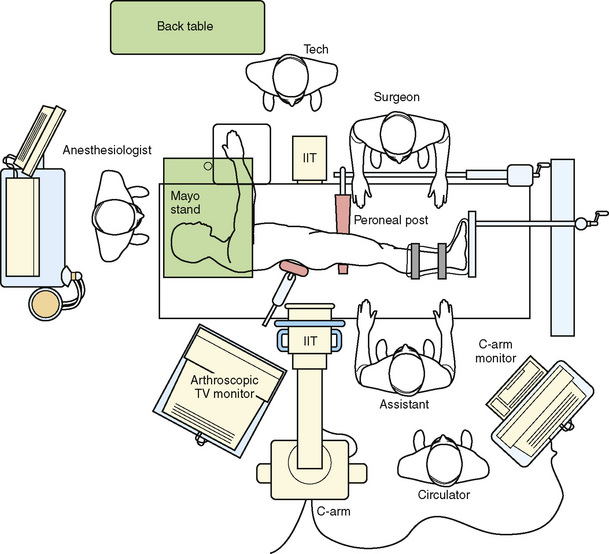

The patient is placed on a well-padded operating room table in the lateral decubitus position (Figure 10-4). An axillary roll is positioned, and hip positioners are used to support the pelvis. By preventing the pelvis from rolling back on the perineal post, the risk of pudendal neuropraxias may be reduced.

We typically drape with split sheets, and we use a large plastic pouch to catch fluids.

Distraction

For optimal viewing and safe surgery, at least 1.2 cm of distraction is required before the femoroacetabular joint (central compartment) is entered. Three commercially available distractors for the lateral approach are available from Mizuho OSI (Union City, CA 94587-1234), Innomed, Inc. (Savannah, GA, 31404), and Smith & Nephew. The Mizuho OSI and the Smith & Nephew distractors have the advantage in that hip mobility is adjustable during surgery (Figure 10-5).

The perineal post should have padding of at least 9 cm in diameter, and it should be positioned eccentrically over the pubic symphysis, with little to no compression to the downside thigh (Figure 10-6).

Operating room setup

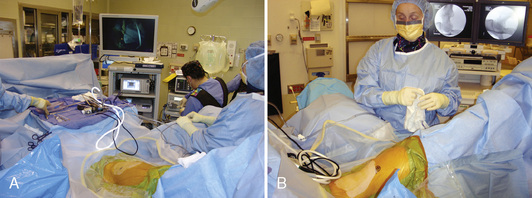

The Tower

The arthroscopic tower with the monitor and instrument boxes should be placed posterior and slightly cephalad adjacent to the C-arm for optimal viewing of all the settings by the surgeon. The cords from the tower are brought onto the Mayo stand and organized for the surgeon to easily reach for the shaver and wands. It is more efficient and safe for the Mayo stand to act as neutral ground that only one person accesses to avoid accidental glove punctures or lacerations (Figure 10-7, A and B).

The procedure

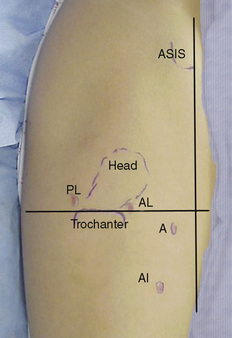

The portals for the lateral approach are nearly identical to the supine approach, except the anterior portal is located approximately 2 cm lateral to the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) line. As a result, the anterior portal courses in an intermuscular plane between the sartorius and the tensor fascia lata (Figure 10-8).

If it is difficult to advance into the joint, suspect that the wire is going through the labrum. In such instances, it is best to start over and to reposition the needle to avoid labral avulsions or tears. In some cases, with stiff hips, the anterior capsule is very thick and very difficult to penetrate. In that situation, it is best to begin with the posterolateral portal or to gently cut the capsule with a long Beaver blade through the arthroscopic sheath before advancing into the joint. Entry into the joint should always be controlled to avoid damaging the labrum or scuffing the cartilage. However, pushing a cannula through the anterior hip capsule is difficult and requires a lot of force as compared with any other joint in the body (Figure 10-9).

Introduce a 30-degree arthroscope, and visually sweep the joint under air or fluid. Next, create the anterior and posterolateral portals with the use of the same technique and with the added benefit of viewing the entry of the needle, the Nitinol wire, and the instruments under direct vision to prevent injury to the cartilage and the labrum. We feel that this approach is much safer and that iatrogenic injury is reduced. When creating the anterior portal, take care to only incise the skin superficially to avoid the laceration of a branch of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve. Spreading through the subcutaneous tissue with a clamp is also advised for this portal (Figure 10-10).

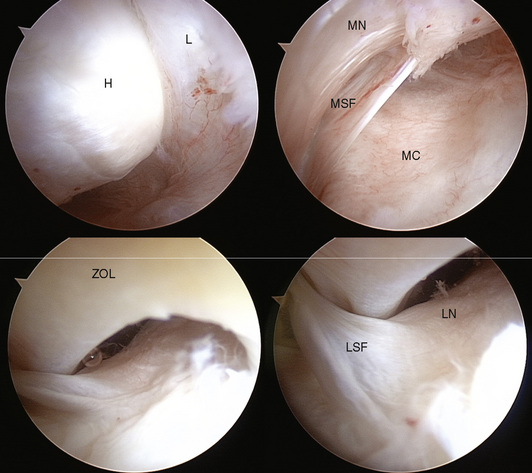

The visual sweep and anatomy

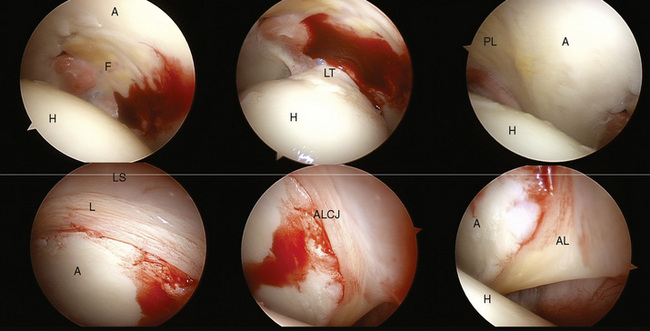

The acetabulum and its structures are viewed first. Initially, the femoral head cannot be entirely viewed with the hip distracted. However the hidden portions will be observed when the peripheral compartment is inspected later during the procedure (Figure 10-11).

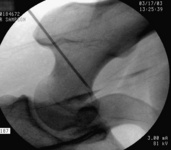

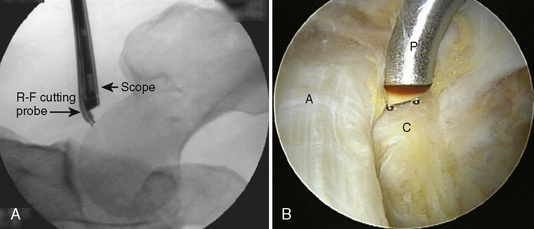

With the hip in slight flexion and neutral rotation, the 17-gauge needle is inserted through the anterolateral portal along the femoral neck toward the head–neck junction. While this procedure is observed under fluoroscopy, a small pop is felt as the needle passes through the capsule, and the effusion dribbles out of the needle (Figure 10-12). A Nitinol wire is passed and bounced off of the medial capsule to confirm that it is intra-articular. The arthroscopic sheath is advanced over the wire, and then the anterior, medial, inferior, and posterior peripheral spaces can be viewed.

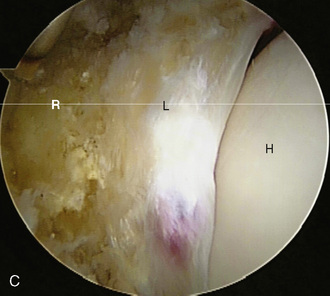

As the scope is withdrawn, rotate it, and then advance it anterior medial and inferior to appreciate the reflection of the iliopsoas tendon on the capsule. The tendinous bulge on the capsule is usually opposite the inferior synovial fold at the head–neck junction; it should not be mistaken for the zona orbicularis. Flexing the hip will relax the capsule for a larger field of view, and this improves the mobility of the scope and the operative instruments (Figure 10-13). An anteroinferior portal may be created at the level of the femoral neck midway between the head–neck junction and the lesser trochanter for both the arthroscope and the operative instruments. A far anteroinferior portal may be used at the level of the lesser trochanter for iliopsoas release.

Technical Pearls

Annotated references and suggested readings

Burman M.S. Arthroscopy or the direct visualization of joints: an experimental cadaver study. J Bone Joint Surg.. 1931;13:5-9.

Byrd J.W., Chern K.Y. Traction versus distension for distraction of the joint during hip arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 1997;13(3):346-349.

This study shows that distention may facilitate distraction but the degree is variable..

Byrd J.W. Hip arthroscopy utilizing the supine position. Arthroscopy. 1994;10(3):275-280.

Byrd J.W., Pappas J.N., Pedley M.J. Hip arthroscopy: an anatomic study of portal placement and relationship to the extra-articular structures. Arthroscopy. 1995;11(4):418-423.

Eriksson E., Arvidsson I., Arvidsson H. Diagnostic and operative arthroscopy of the hip. Orthopedics. 1986;9(2):169-176.

Farjo L.A., Glick J.M., Sampson T.G. Hip arthroscopy for acetabular labral tears. Arthroscopy. 1999;15(2):132-137.

JM Glick., TG Sampson., RB Gordon., et al. Hip arthroscopy by the lateral approach. Arthroscopy. 1987;3(1):4-12.

Glick J.M., Sampson T.G. Hip arthroscopy by the lateral approach. In: McGinty J.B., editor. Operative arthroscopy. Philadelphia and New York: Lippincott-Raven; 1996:1079-1090.

Griffin D.R., Villar R.N. Complications of arthroscopy of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br.. 1999;81(4):604-606.

Ilizaliturri V.Jr, Villalobos F.Jr, Chaidez P., et al. Internal snapping hip syndrome: treatment by endoscopic release of the iliopsoas tendon. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(11):1375-1380.

Sampson T.G., Glick J.M. Indications and surgical treatment of hip pathology. In: McGinty J.B., editor. Operative arthroscopy. Philadelphia and New York: Lippincott-Raven; 1996:1067-1078.

Sampson T.G. Complications of hip arthroscopy. Clin Sports Med.. 2001;20(4):831-835.

Sampson T.G. Arthroscopic iliopsoas release for coxa saltans interna (snapping hip syndrome). In: Byrd J.W., editor. Operative hip arthroscopy. New York: Springer; 2005:189-194.

Sampson T. Hip morphology and its relationship to pathology: dysplasia to impingement. Operative Techniques in Sports Medicine. 2005;13(1):37-45.

Sampson T.G. The lateral approach. In: Byrd J.W., editor. Operative hip arthroscopy. New York: Springer; 2005:129-144.

Sampson T.G. Arthroscopic treatment of femoroacetabular impingement: a proposed technique with clinical experience. Instr Course Lect.. 2006;55:337-346.

Thomas Byrd J.W. Indications and contraindications. 2nd edition. Operative hip arthroscopy, 2005. Springer

Villar R. Hip arthroscopy. J Bone Joint Surg Br.. 1995;77(4):517-518.