CHAPTER 3 Laparoscopy

History

Examination of the body cavities using instrumentation has been practised by clinicians over many centuries. Most of the early techniques involved inspection of the bladder and urethra (Bozzini 1805). Light sources were introduced initially with alcohol flames (Desmoreaux 1865), and subsequently the incandescent light bulb. The first inspection of the peritoneal cavity was through the posterior fornix in the early 20th Century (von Ott 1901). Examination of other cavities was described soon afterwards (Jacobaeus 1910), with carbon dioxide used for insufflation more than a decade later (Zollikoffer 1924). The first diagnosis of an ectopic pregnancy followed (Hope 1937), as did female sterilizations. Veress first reported the spring-loaded insufflation needle as a technique for introducing a pneumothorax in patients with tuberculosis (Veress 1938).

Further advances were relatively slow with few clinicians inspired by the new techniques. The first description of sterilization in English was not until 25 years later (Steptoe 1967). Few therapeutic procedures were performed laparoscopically, although the technique gained widespread support for diagnosis.

The revolution in therapeutic techniques probably started with the report of the first laparoscopic hysterectomy (Reich et al 1989) and, with advances in instrumentation, light sources and camera systems, continued apace throughout the 1990s. However, a few practitioners attempted procedures that were beyond either their surgical training or ability, and responsible bodies rapidly concluded that regulation was required. The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) established its training guidelines in 1994 with certification for those trained to perform at different levels. This has been repeatedly modified to bring the UK training into line with practice in other European countries.

Theatre Set-Up

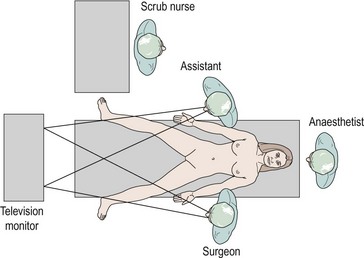

The authors believe that the television screen should be placed between the patient’s legs if the camera is inserted at the umbilicus. Figure 3.1 demonstrates that the view displayed on the screen is in the same direction in which the patient is lying and the surgeon operating. Many experienced surgeons place the television screen directly in front of themselves and behind the assistant. Under these circumstances, the surgeon is operating in a different direction to which he or she is looking; not only is this uncomfortable and ergonomically disadvantageous, but all images have to be transposed through 90 degrees, adding to the difficulties of hand–eye coordination. The additional advantage of placing the monitor between the patient’s legs is that only one screen is required.

The scrub nurse should stand in a consistent position, and instrumentation such as bipolar diathermy, scissors, graspers and suction irrigation should be placed reliably within easy reach of the surgeon. The scrub nurse should be within sight of the television screen, enabling anticipation of the next instrument required. A protective bar placed across the table prevents the assistant’s arm from resting on the upper part of the patient and potentially dislodging the endotracheal tube (Figure 3.2).

Equipment

The following items are essential.

Trocars

Many different types of trocar are available, which vary in size, length and design of the tip (Figure 3.3). The 12 mm, 10 mm and 5 mm trocars are used most commonly in gynaecological surgery. When performing complicated surgery, there can be many changes of instrument down any individual port. For this reason, the trocars have to be able to grip the abdominal wall, and there are various designs to facilitate this. Some of the more modern trocars have a type of ‘fish scale’, whilst others utilize a screw thread which can grip more effectively but increases the diameter of the incision. The trocar tip can be conical, pyramidal or a single flat blade in design. They create different sized and shaped incisions in the fascia, with the single flat blade and conical dilating tip producing the smallest defect. Optical trocars have a blunt clear dome-shaped tip housing a crescent-shaped blade. They allow a controlled sharp dissection of the abdominal wall layers under direct vision. These trocars can be inserted prior to insufflation and may be useful in obese patients with thick abdominal walls. Trocars may be disposable or reusable. Many laparoscopic surgeons have been persuaded to use disposable trocars because of their constantly sharp tips, the so-called safety devices to retract the tip when through the full thickness of the abdominal wall and to avoid contamination between patients. However, most surgical units find the cost of disposable trocars prohibitive for use with every case.

Camera system

Modern camera systems are an essential part of the laparoscopic surgeon’s equipment. There are few surgeons around the world who continue to operate by looking directly down the eyepiece of the laparoscope, even for minor diagnostic procedures. There is a clear advantage in being able to project the image on to a television screen that is visible to all members of the surgical team. Together with the ergonomic advantages of not having to stoop over the patient, this means that camera systems are now commonplace. The image seen through the eyepiece of the laparoscope is converted into electrical signals by a charge-coupled device housed in the camera head. These electrical signals are then processed by the camera control facility which is, in turn, connected to the television monitor. Cameras may contain one or three charge-coupled devices, each of which is colour specific, recording only one of the three primary colours. Most modern camera systems enable collection of digital images which are projected on to a digital monitor, although hybrid set-ups can co-exist. Some camera heads incorporate remote buttons to allow the operator to control various features of the imaging system, such as taking prints, operating the video recorder or white balancing. Some cameras are autoclavable but the majority of surgeons will place the camera system inside a sterile plastic sheath before connecting to the laparoscope (Figure 3.4).

Operating instruments

There are innumerable types of operating instruments, and individual surgeons will have their own preferences. Essentially, the instruments can be divided into the jaws, the shaft and the handles. Jaws have been designed which mimic all the instrumentation available for open surgery, plus many others. Examples are shown in Figure 3.5. The shafts may be of 10, 5 or 3 mm diameter and may or may not contain a diathermy attachment. For non-disposable instrumentation, it is often the shaft that is the most difficult part of the instrument to keep clean and maintain. Handles come in a variety of ergonomic designs, according to surgeon preference. Handles may be ratcheted or non-ratcheted in a variety of ways. Most non-disposable instruments have a detachable handle in order to convert an instrument into one with or without a ratchet. Surgeons have their favourite graspers and, as with most situations, it is more important to be familiar with an instrument and to know its limitations than it is to have a wide variety of instrumentation that is less familiar.

Port Entry

A variety of techniques have been described for insufflation in order to allow the surgeon to view the pelvic and abdominal contents through the laparoscope. A great deal of discussion has occurred, particularly in medicolegal circles, regarding which is the safest technique. Complication rates for laparoscopy are so low that individual surgeons are unlikely to be able to evaluate the various entry techniques in their own practice. However, the number of laparoscopies performed is so high that the overall effect of an inferior technique could be significant for a number of patients around the country each year. Traditionally, gynaecologists are familiar with the closed technique, having performed many diagnostic laparoscopies in their training. General surgeons perform fewer laparoscopies, and these are usually for major procedures. They are usually more familiar with the open technique. Each technique has its persuasive advocates basing their arguments on a combination of scientific evidence and personal bias. Methods of port entry were examined by a recent Cochrane review which concluded that there was no evidence that one method was superior (Ahmad et al 2008).

Site of entry

At the umbilicus, the abdominal wall is at its thinnest. A subumbilical incision is preferred by some clinicians, but there appears to be no logic to this. If the umbilicus is to be used, there is little point in inserting either the Veress needle or primary trocar at a point where the abdominal wall has expanded. In addition, an intraumbilical incision is cosmetically superior (Figure 3.6). The left upper quadrant of the peritoneal cavity is where the fewest intraperitoneal adhesions occur. For this reason, Palmer suggested the ninth intercostal space as an insertion point for insufflation and brief inspection of the peritoneal cavity. A number of clinicians utilize this entry point when they suspect that periumbilical adhesions may be present.

Closed laparoscopy

A vertical incision is made intraumbilically, with the angle of the Veress needle insertion varying according to the body mass index (BMI) of the patient, from 45 degrees in non-obese women to 90 degrees in obese women (Figure 3.7). Most clinicians stabilize the anterior abdominal wall by grasping it with the left hand, while the right hand inserts the Veress needle. Experienced laparoscopists can feel the Veress needle pass through the layers of the anterior abdominal wall, and will usually be able to tell whether the Veress needle is correctly positioned. At this point, a number of techniques have been described to assist in demonstrating that the Veress needle is correctly positioned. A syringe can be used to aspirate from the Veress needle to identify visceral contents. Alternatively, a droplet of water or saline can be placed on the end of the Veress needle and the negative intra-abdominal pressure causes this to be sucked in. A syringe placed on the end of the Veress needle and containing water or saline, but without its plunger, will usually allow the solution to drip into the peritoneal cavity if correctly positioned. Once insufflation is commenced, the filling pressure can be observed and uniform distension of the abdominal cavity can be determined by percussion. In particular, the area over the liver becomes resonant to percussion when pneumoperitoneum is created. ‘Waggling’ of the Veress needle from side to side should be avoided as this can enlarge a 1.6 mm puncture injury to an injury of up to 1 cm in viscera or blood vessels.

It is important to create pneumoperitoneum of a set pressure rather than volume. The size of the intraperitoneal cavity varies greatly between individuals. The purpose of insufflation is to provide a cushion between the anterior abdominal wall and the important underlying structures when the primary trocar is inserted. Phillips et al (1999) demonstrated that an intraperitoneal pressure of 25 mmHg was necessary in order to maintain the gas bubble during insertion of the primary trocar. It is extremely important that this pressure is then reduced to 15 mmHg or less for the rest of the operation. Ventilation difficulties are not encountered at this initial filling pressure, as the patient is flat and the pressure of this level is only maintained for a short period of time.

Direct entry

Direct trocar insertion without pneumoperitoneum using an optical trocar can be employed but there is insufficient evidence to suggest any benefit over the open or closed techniques (Ahmad et al 2008). A disadvantage of this technique is that any inadvertent visceral perforation is guaranteed to be of significant size, unlike damage caused by the Veress needle. Direct entry is increasingly employed in the morbidly obese undergoing gastric bypass surgery.

Open laparoscopy

The Hasson entry technique was first described in 1971 (Hasson 1971). A vertical incision is placed intraumbilically and the various layers of the abdominal wall are incised using two Langenbeck retractors on either side to assist with visualization. Once the rectus sheath is incised, a suture is inserted on either side of the incision into the sheath. The peritoneum is opened, a blunt Hasson cannula is inserted directly into the peritoneal cavity and insufflation is commenced. A seal is usually created utilizing the sutures in the rectus sheath and tightening around a cone attached to the Hasson cannula.

Comparison of complications

A vast number of laparoscopies using the closed technique have been performed over many years. A collection of over 350,000 procedures has calculated the risk of bowel damage to be 0.4/1000 and the risk of major vessel injury to be 0.2/1000. The most common bowel injury is to the transverse colon, while the most common vascular injury is to the right common iliac artery (Clements 1995).

There are no comparable data on such a large number of patients for open laparoscopy. One rationale of the Hasson technique is to identify intraperitoneal and bowel adhesions at entry into the peritoneal cavity, thus avoiding blind insertion of a trocar into a visceral structure, but this was not supported by a recent Cochrane review (Ahmad et al 2008). More logically, the Hasson technique avoids major vessel damage. Population-based studies are an inappropriate way of comparing the two techniques, as many clinicians only use the open laparoscopy approach if they think there is a danger of intraperitoneal adhesions. They are therefore selecting a high-risk group of patients on which to perform this technique. Studies that have been published with large numbers suggest that bowel damage in the open laparoscopy group is equivalent to that in the closed laparoscopy group (Chapron et al 1998).

Advocates of the open laparoscopy approach maintain that the time taken to achieve pneumoperitoneum is equivalent to that of the closed laparoscopy approach (Pickersgill et al 1999).

Ten percent of patients will have intra-abdominal adhesions, with 5% having severe adhesions containing bowel around the umbilicus. Ninety-two percent of these patients with severe adhesions will have had a previous laparotomy, with the vast majority following midline incisions (Garry 2000). Although not all visceral perforations caused by laparoscopy are the result of negligence, it would seem prudent for clinicians to take previous midline laparotomies into consideration when performing a laparoscopy. It is important that those advocates of closed laparoscopy are able to perform open laparoscopy when their own technique fails. There is currently no conclusive proof that one technique is safer than the other, and a huge randomized controlled trial would be necessary to detect small safety differences between the two techniques.

Teaching and Learning

Many trainers have recognized the value of simulating exercises in the training of laparoscopic surgeons, so laboratories have been established to teach and assess practical skills in a variety of centres around the country. Hand–eye coordination exercises are now widespread and many are quite imaginative. Computer simulations play an increasing part in the training of laparoscopic surgeons. Exercises based on surgical procedures are available through the i-sim® system (www.isurgicals.com). Simulators have been shown to improve surgical performance whilst learning a new technique (Aggarwal et al 2006). It is perfectly logical to assume that, in the future, surgeons will have to demonstrate their competence on these virtual reality systems before being allowed to operate on patients. Reproducible tests of dextrous ability can be used as part of the assessment process when determining which candidate should be appointed to a particular specialty post.

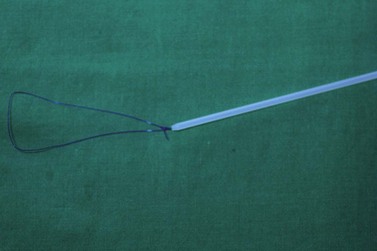

Pre-tied sutures

The endo-loop is a simple technique for applying a suture to a pedicle, pushing down a pre-tied knot (Figure 3.8). These pre-tied sutures employ a Roeder knot and are extremely useful either as a time-saving device or for less-experienced laparoscopic surgeons.

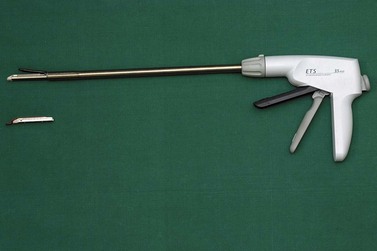

Stapling

Mechanical stapling devices have helped to revolutionize laparoscopic surgery and encouraged a generation of surgeons to utilize these precision instruments (Figures 3.9 and 3.10). The device usually inserts three lines of carefully arranged titanium staples, either side of a knife tract, which allows the tissue to be divided when the staples are fired. It is an extremely efficient and rapid instrument, but its major disadvantage is its diameter which requires a 12 mm port. They do need to be applied with great care, and the surgeon needs to ensure that only the desired tissue is secured within the jaws of the device. In the use of this instrument, the surgeon has to be particularly aware that the view on the monitor is only provided in two dimensions. The tips of the stapling device must be visualized before firing.

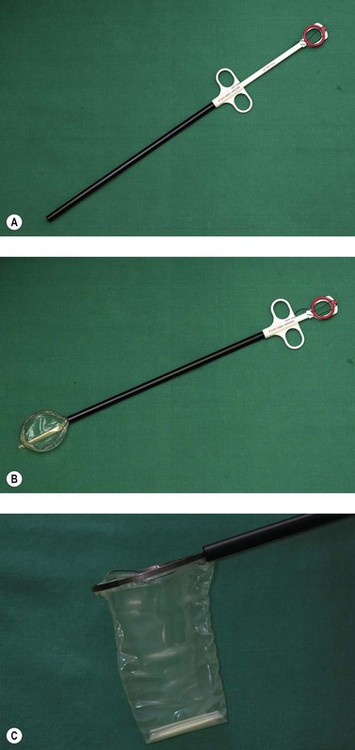

Specimen removal

Many laparoscopic operations are initially straightforward, such as an oophorectomy for a large ovarian cyst. Very often, the most difficult part of the procedure is actually removing the specimen without increasing the size of the incisions in the abdominal wall. A number of devices have been employed in order to make this extraction easier. The most commonly used specimen retrieval system utilizes a bag such as the Endo-catch bag in Figure 3.11. The bag comes pre-folded and springs open once inserted into the abdominal cavity, allowing the specimen to be inserted. The edges of the bag are brought to the surface and the specimen removed without spilling its contents into the peritoneal cavity. A large cyst can be deflated extracorporeally for easy removal.

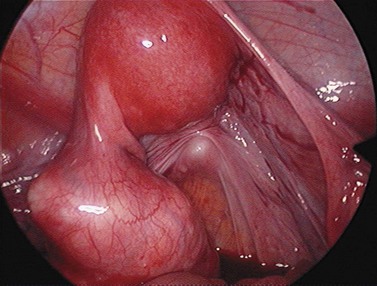

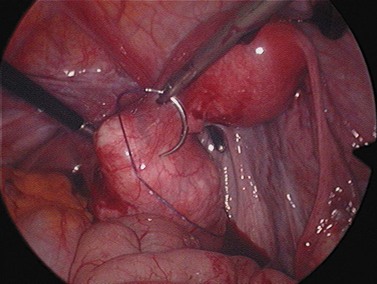

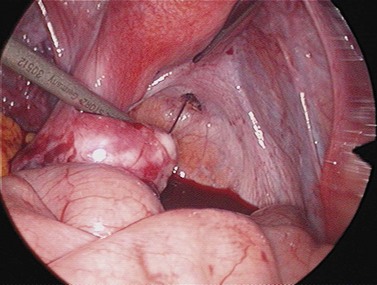

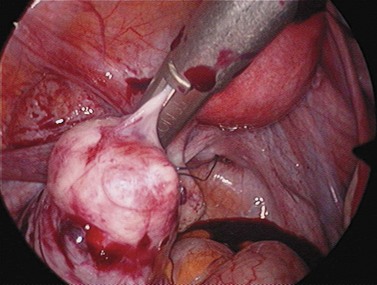

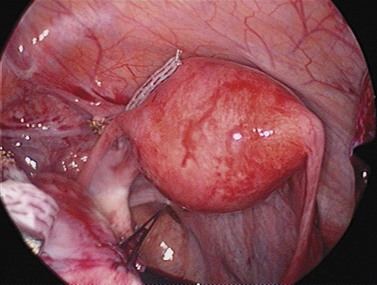

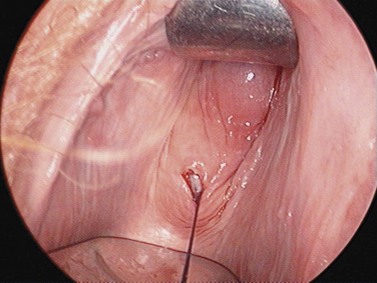

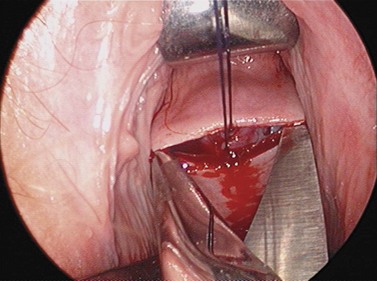

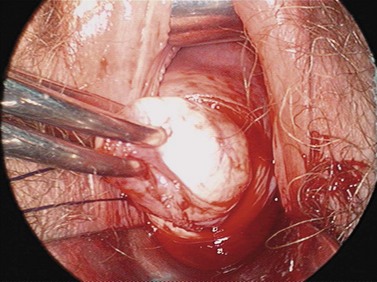

For larger cysts and more solid structures, such as fibroids, alternative methods of specimen removal may be necessary. A posterior colpotomy can be extended with ease to 4 or 5 cm diameter without increasing discomfort or recovery time for the patient. Large-volume specimen bags can be inserted through the posterior fornix and wrapped around large ovarian cysts or fibroids. The neck of the bag can be brought through the incision in the posterior fornix, and the specimen either morcellated or deflated through a much larger incision than is required for the abdominal ports. Figures 3.12–3.20 demonstrate the removal of a 7 cm pedunculated fibroid using a posterior colpotomy. Initially, the fibroid is fixed with a suture to avoid it being displaced into the upper abdomen under the influence of gravity once it is disconnected from the uterus (Figures 3.13–3.14). A straightforward Endo-GIA staple disconnects the fibroid from the uterus and the fibroid is brought down to the posterior colpotomy by pulling on the suture (Figures 3.15–3.17). Transvaginally, the posterior colpotomy is extended and the fibroid morcellated to remove the specimen (Figures 3.18 and 3.19). The posterior colpotomy is repaired either vaginally or laparoscopically with precision.

Energy sources

Many energy sources are available for use with laparoscopic instruments. Bipolar and monopolar diathermy are widely available and reliable. The use of lasers is covered elsewhere in this text (see Chapter 4). Newer methods of tissue division and vessel sealing include the Harmonic Scalpel® and the Ligasure® system. Progress in this area of technology has allowed many diagnostic laparoscopies to be converted into effective therapeutic treatment.

Gasless laparoscopy

It is possible to operate within the peritoneal cavity without distending it using carbon dioxide (Chin et al 1993, Wood et al 1994). A rigid mechanical support is required in order to elevate the anterior abdominal wall so that the viscera can be identified. The advantages of gasless laparoscopy are the avoidance of insufflators causing possible gas emboli, and the use of simpler trocars. However, most gasless laparoscopy techniques require extra portals in order to insert the mechanical device for visualization. It is not a technique that has become widespread.

Robotic techniques

Robots were first used in humans to carry out a transurethral resection of the prostate in 1991 at Imperial College, London (Davies et al 1997). The controls of modern robots have an intuitive ease of use, and complex manoeuvres such as suturing can be easily mastered. Physiological movement can be digitally subtracted from the camera signal to give a still image on the screen; for example, cardiac pulsation can be dampened down. The surgeon can be remote from the patient, even in another continent. In an era of consumer-driven health care, there is increasing demand for the most up-to-date equipment. Disadvantages of the robot include limited haptic feedback so the operator is unable to gauge the force applied to the tissue. The robot is an expensive and complex piece of equipment requiring careful maintenance, and in the event of a malfunction, the surgeon must be prepared to complete the operation either laparoscopically or as an open procedure. Operations performed robotically include radical prostatectomy, beating heart bypass grafts and radical hysterectomy.

Complications of Laparoscopy

The complications associated with port entry have been mentioned earlier in this chapter, and this is generally the most dangerous time for the patient. However, laparoscopic surgery can have many of the same complications as open surgery, depending on the complexity of any procedure. A list of possible complications is seen in Box 3.1.

Uses of Laparoscopy

Therapeutic

If a therapeutic laparoscopic procedure can be performed with ease and without putting the patient in increased danger, there is no question about its efficacy. Clinicians would agree that a diagnostic laparotomy is unnecessary, has a long recovery period and significant minor morbidity. It is therefore logical to extend this principle into the area of therapeutics. There are many procedures that are clearly better performed laparoscopically, and these should be made available to all patients. It is the responsibility of health authorities, hospital administration and local clinicians to ensure that this logical and sensible approach is available for their patients. Examples of procedures that should normally be performed laparoscopically are given in Box 3.2.

The frequently quoted paper from Dicker et al (1982), where one-third of hysterectomies were performed vaginally, demonstrates a faster recovery time and lower minor morbidity rate by this route. Major morbidity was infrequent in both groups, but considerably higher in the vaginal hysterectomy group. It seems logical that an easy vaginal hysterectomy would have minimal major complications and provide the patient with the shortest recovery period. However, as the procedure becomes more difficult, the possibility of major complications increases. Judging when to dismiss the advantages of shorter recovery and look for the lower major morbidity rate is an issue that has not been standardized.

It is most desirable to perform a vaginal hysterectomy under the easiest circumstances, but when the procedure is extremely difficult, an abdominal hysterectomy is preferable. At some point between these two extremes, the lines cross. Laparoscopic hysterectomy was introduced in an attempt to make some of the more difficult vaginal hysterectomies easier. As a consequence, many patients who would have otherwise had an abdominal hysterectomy were offered a laparoscopic hysterectomy or a laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy. The effects of the route of hysterectomy were examined in 1347 women in the eVALuate study (Garry et al 2004). The trial had two arms; one arm compared abdominal with laparoscopic hysterectomy, and the second underpowered arm compared vaginal and laparoscopic routes. The abdominal arm showed a higher risk of complications including ureteric injuries and conversion to laparotomy with the laparoscopic route, but also less pain and a shorter hospital stay. The vaginal arm showed a longer duration of operation with the laparoscopic route compared with the vaginal route. The trial has been criticized for the low number of laparoscopic hysterectomies performed by each surgeon. The complications may have been higher due to the learning curve of the surgeons. In addition, conversion to open surgery was recorded as a major complication, which may have encouraged surgeons to persist against their better judgement.

KEY POINTS

Aggarwal R, Tully A, Grantcharov T, et al. Virtual reality simulation training can improve technical skills during laparoscopic salpingectomy for ectopic pregnancy. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2006;113:1382-1387.

Ahmad G, Duffy JM, Phillips K, Watson A 2008 Laparoscopic entry techniques. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2.

Audebert AJM. Laparoscopic ovarian surgery and ovarian torsion. In: Sutton C, Diamond MP, editors. Endoscopic Surgery for Gynecologists. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1998.

Bozzini P. Der lichtleiter odere beschreibung einer eingachen vorrichtung und ihrer anwendung zur erleuchung innerer hohlen und zwischeraume deslebenden animaleschen corpses. Weimer: Landes-Industrie-Comptoi; 1805.

Chapron C, Querleu D, Bruhat MA, et al. Surgical complications of diagnostic and operative gynaecological laparoscopy: a series of 29,966 cases. Human Reproduction. 1998;13:867-872.

Chin AK, Moll FH, McColl MB, Reiv H. Mechanical peritoneal retraction as a replacement for carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum. Journal of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists. 1993;1:62-66.

Clements RV. Major vessel injury. Clinical Risk. 1995;1:112-115.

Davies BL, Harris SJ, Arambula-Cosio F, Mei Q, Hibberd RD. The Probot — an active robot for prostate resection. Proceedings of the Institute of Mechanical Engineers, Part H, Jl. Engineering in Medicine. 1997;211:317-326.

Dicker RC, Scally MJ, Greenspan JR, et al. Hysterectomy among women of reproductive age — trends in USA 1970–78. JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association. 1982;248:323-327.

Desmoreaux AJ. De l’endoscopie et de sas applications au diagnostic et au traitment des affections de l’uretre et de la vessie. Paris: Baillière; 1865.

Dingfelder JR. Direct laparoscopic trocar insertion without prior pneumoperitoneum. Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 1978;21:45-47.

Garry R. Towards evidence based laparoscopic entry techniques: clinical problems and dilemmas. Gynaecological Endoscopy. 2000;8:315-326.

Garry R, Fountain J, Mason S, et al. The eVALuate study: two parallel randomised trials, one comparing laparoscopic with abdominal hysterectomy, the other comparing laparoscopic with vaginal hysterectomy. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.). 2004;328:129.

Hasson HM. A modified instrument and method for laparoscopy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1971;110:886-887.

Hope R. The differential diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy in peritoneoscopy. Surgery, Gynecology and Obstetrics. 1937;64:229-234.

Jacobaeus HC. Uber due Moglichkeil die Zystoskopie bei Untersuchlung seroser Hohlungen anzerwerden. Munchener Medizinische Wochenschrift. 1910;57:2090-2092.

Phillips G, Garry R, Kumar C, Reich H. How much gas is required for initial insufflation at laparoscopy? Gynaecological Endoscopy. 1999;8:369-374.

Pickersgill A, Slade RJ, Falconer GF, Attwood S. Open laparoscopy: the way forward. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1999;106:1116-1119.

Reich H, DeCaprio J, McGlynn F. Laparoscopic hysterectomy. Journal of Gynecologic Surgery. 1989;5:213-216.

Steptoe PC. Laparoscopy in Gynaecology. Edinburgh: E&S Livingstone; 1967.

Sutton CJG, Ewen SP, Whitelaw N, Haines P. Prospective, randomised, double-blind controlled trial of laser laparoscopy in the treatment of pelvic pain associated with minimal, mild, and moderate endometriosis. Fertility and Sterility. 1994;62:696-700.

Veress J. Neues instrument fur ausfuhrung von brust-oder brachpunktionen und pneumothoraxbehandlung. Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift. 1938;104:1480-1481.

von Ott D. Ventroscopic illumination of the abdominal cavity in pregnancy. Zhurnal Akrestierstova I Zhenskikh Boloznei. 1901;15:7-8.

Wood G, Maher P, Hill D. Current states of laparoscopic associated hysterectomy. Gynaecological Endoscopy. 1994;3:75-84.

Yao M, Tulandi T. Current status of surgical and nonsurgical management of ectopic pregnancy. Fertility and Sterility. 1997;67:421-433.

Zollikoffer R. Zur Laparoskopie. Schwizerische Medizinische Wochenschrift. 1924;15:264-265.