Chapter 50 Laparoscopic Management of Adnexal Masses

INTRODUCTION

Laparoscopic management of an adnexal mass was first reported more than 30 years ago. During the past decade, laparoscopy has become the dominant management technique for the majority of adnexal masses. Curiously, laparoscopy was accepted as a better approach than laparotomy for adnexal masses with little supporting experimental evidence. This is similar to the widespread acceptance of laparoscopic cholecystectomy, despite a randomized, blinded trial that concluded that the open technique was superior.1

ADNEXAL MASSES: DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS AND BIOLOGY

Extra-ovarian Adnexal Masses

Although the ovary is the most common origin of an adnexal mass, the source can also be the fallopian tubes, the uterus, and even bowel. From any of these organs, a mass can result from hypertrophy, neoplasm, or infection. In a study of 656 women with persistent adnexal masses, 9% were found to originate outside the ovary.2 For this reason, the differential diagnosis of an adnexal mass should always include both ovarian and extraovarian sources (Table 50-1).

| Ectopic pregnancy |

| Hydrosalpinx |

| Tubo-ovarian abscess |

| Paraovarian cyst |

| Peritoneal inclusion cyst |

| Leiomyoma |

| Fallopian tube neoplasm |

| Bowel abscess or neoplasm |

Ovarian Tumors

Functional Ovarian Cysts

Despite the fact that these physiologic or functional cysts often resolve spontaneously over time, more than 30% of laparoscopies performed to evaluate and manage adnexal masses ultimately find a functional or simple ovarian cyst.3

In some cases, hemorrhage into a functional cyst at the time of ovulation can result in ovarian enlargement and persistent pain. Ultrasonography in these cases will reveal a characteristic complex cyst partially filled with areas of high echodensity. The sudden occurrence of symptoms near midcycle and the spontaneous resolution of the cyst over weeks to months differentiate a hemorrhagic corpus luteal cyst from endometriomas or other more ominous lesions.

Endometriomas

Endometriomas often pose a difficult management challenge. The most likely cause of endometriosis is retrograde menstruation, as first proposed by Sampson in 1927. Patients with this disease are believed to have some other deficiency, because retrograde flow of endometrial cells occurs in 90% of women, but most of them never develop endometriosis.4

Several clinical risk factors have been identified that increase the risk that any ovarian mass will be a malignant neoplasm. One of the most important is age. Before age 15, many ovarian tumors are malignant.5 In woman between ages 20 and 45, only the minority of ovarian tumors will be malignant. The risk increases with age thereafter, such that an ovarian tumor discovered in a woman between ages 60 and 69 is 12 times more likely to be malignant than a tumor in a woman between ages 20 and 29.6 Other important risk factors for malignant tumors include a positive family history and nulliparity.

SPECIFIC OVARIAN NEOPLASMS

Epithelial Cell Tumors

Serous and mucinous tumors are the most common ovarian epithelial cell tumors, and the majority are benign (Table 50-3). The fact that they are mostly benign allows a laparoscopic approach.

| Type | Percent of Tumor Type |

|---|---|

| Serous | |

| Benign | 60% |

| Borderline | 15% |

| Malignant | 25% |

| Mucinous | |

| Benign | 80% |

| Borderline | 10% |

| Malignant | 10% |

| Teratoma | |

| Benign | 96% |

| Malignant | 4% |

From Cotran RS, Kumar V, Collins T, Robbins SL: Robbins Pathologic Basis of Disease. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1999.

Serous

Malignant serous cystadenocarcinomas are the most common ovarian malignancies, accounting for almost 50% of all malignant ovarian tumors. They are the fifth most common cancer in women in the United States. These tumors usually occur in women between ages 40 and 65 and are bilateral in 65% of cases.

Germ Cell Tumors

Chemical Peritonitis

A unique management concern regarding benign cystic teratomas is that untreated intraperitoneal spill of their sebaceous contents can result in chemical peritonitis. Clinically, patients present with postoperative fever and ileus, and can develop peritoneal granulomas, adhesions, and even a perihepatic mass.7,8

The risk of chemical peritonitis has two implications for the laparoscopic surgeon. First, if a cyst punctured during laparoscopy is found to contain sebaceous material, a cystectomy or oophorectomy should immediately be performed. Leaving behind a leaking teratoma can lead to serious consequences. Second, when a dermoid cyst is removed laparoscopically, cyst rupture (reported to occur in approximately half the cases) must be appropriately treated with copious irrigation (i.e., 2 to 5L) until no oily material can be seen floating on the fluid surface.9–11 Subsequent peritonitis has not been reported using this approach after spillage from a mature cystic teratoma.

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION OF AN OVARIAN MASS

The most important diagnostic questions to be answered before surgery are (1) What is the origin of the mass? and (2) Is it benign or malignant? Although bimanual pelvic examination is the time-honored method of screening for pelvic masses, this technique has marked limitations for evaluating adnexa, especially in the presence of obesity, uterine enlargement, or abdominal scarring.12 History, physical examination, and ultrasonography can usually determine the origin of an adnexal mass.

For ovarian masses, a combination of pelvic examination, ultrasonography, and serum CA-125 level is the best way to determine the risk of malignancy.12–14 Certain ultrasonographic characteristics have been found to be strongly associated with malignancy (see Chapter 30). Ovarian tumors are more likely to be malignant if ultrasonography reveals them to be multiloculated, septated, mixed cystic and solid, bilateral, or associated with ascites.15 However, almost two thirds of multilocular and solid tumors will be benign.16,17

Combining serum CA-125 with these ultrasound criteria has been used in women who are postmenopausal as the risk of malignancy index.15 Other investigators have found color flow Doppler ultrasonography to be helpful, because an ovarian lesion is more likely to be malignant if a solid element of the mass demonstrates central blood flow.18

Multiple preoperative assessment models have been developed for adnexal masses.16–28 A significant limitation of many of these models is that they were developed and validated on the same population. Mol and colleagues tested the external validity of most of these models and found that although they could be of value in preoperative assessment, their diagnostic performance was not as good as reported in their original publications.27

None of the externally validated likelihood ratios are sufficiently great as to be diagnostically conclusive.27 Likelihood ratios are the likelihood that a given test result would be expected in a patient with the target disorder compared to the likelihood that that same result would be expected in a patient without the target disorder. Although likelihood ratios may not be as familiar a concept as sensitivity and specificity, they are calculated from these values and are a more logical means of understanding diagnostic value. Pretest probability can be multiplied by the likelihood ratio of a given test to render the post-test probability. Likelihood ratio values can be positive (rule in a diagnosis) or negative (rule out a diagnosis).

What is curious about these models is the relative consistency of the likelihood ratio results and that additional information, such as age and menopausal status, does not dramatically alter the likelihood ratio results between the studies. Unfortunately, these models have significant rates of false-negative and false-positive results, regardless of the criteria and cutoff values used. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the Society of Gynecologic Oncologists (SGO) have jointly published guidelines that help determine when a women with a newly diagnosed pelvic mass should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist (Table 50-4).29 This conservative model accurately predicts which women with ovarian masses are at low risk of malignancy, with a negative predictive value of 92% for premenopausal and 91% for postmenopausal women.30 However, the women at highest risk according to this model will often be found to have a benign lesion, with a positive predictive value of 34% for premenopausal and 60% for postmenopausal women.

Table 50-4 Society of Gynecologic Oncologists and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Referral Guidelines for a Newly Diagnosed Pelvic Mass*

* Women with pelvic masses who meet these criteria should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist.

From ACOG: The role of the generalist obstetrician-gynecologist in the early delection of ovarian cancer. ACOG Committee Opinion no. 280, December 2002. Obstet Gynecol 100:1413–1416, 2002.

SURGICAL APPROACH

Laparoscopy versus Laparotomy

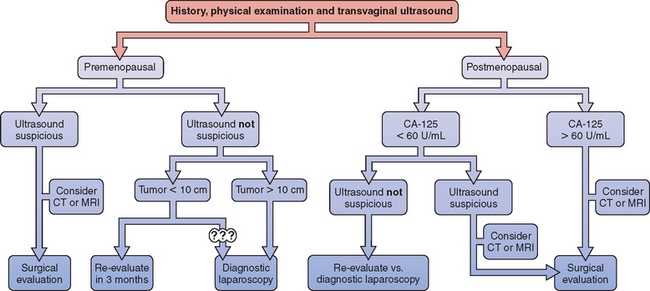

A useful approach for the woman presenting with a pelvic mass has been proposed, which places each patient into one of three risk categories for having a malignancy: low, intermediate, and high (Fig. 50-1).22 A woman at low risk can be observed for 3 months or evaluated with diagnostic laparoscopy according to the patient’s preference. A woman at intermediate risk can be evaluated with diagnostic laparoscopy. Laparoscopic treatment of the mass is appropriate in the absence of surgical evidence of malignancy. Women at high (10% or greater) risk of malignancy should be evaluated surgically, most commonly via laparotomy. In select circumstances, laparoscopy can be used for surgical evaluation, assuming that the laparoscopist has both the appropriate experience and gynecologic oncologist backup.

Intraoperative Tumor Rupture

Intraoperative rupture of some ovarian cysts that are later found to be malignant is unavoidable, regardless of the preoperative criteria or surgical approached used. One study of 32 patients found an overall rate of tumor rupture of 25% for laparoscopy compared to 9% for laparotomy.31 This occurrence appears to worsen the patient’s prognosis, although there are conflicting data. Although some studies have found no impact of intraoperative tumor rupture on subsequent survival,32–34 others have shown decreased survival.35–38

The only prospective assessment of the impact of intraoperative tumor rupture found a significantly lower survival rate for women with stage I ovarian carcinoma after rupture, although not as low as for women whose tumor ruptured spontaneously before surgery.38 The greatest impact of intraoperative rupture was for serous tumors, where the 9-year survival rate declined from 86% to 50%. Furthermore, many oncologists will recommend chemotherapy after an intraoperative spill of a well-differentiated stage I a cancer that usually would not have received such treatment. Certainly, spillage of cyst contents into the peritoneal cavity should be avoided when ovarian malignancy is a possibility.

Surgical Staging

Regardless of the surgical approach used to treat an ovarian malignancy, adequate surgical staging is imperative (Table 50-5). One study of 100 women with ovarian cancer referred to a gynecologic oncologist after surgical diagnosis found that only 25% had adequate staging.39 More than 30% were ultimately found to have more advanced stage disease than reported based on the initial surgery.

One factor that contributes to inadequate staging at the initial surgery is the discordance between intraoperative frozen section and subsequent diagnosis based on permanent section. Making a diagnosis of borderline malignancy is especially difficult on frozen section. Several studies have documented a greater than 5% discordance between these two techniques.40,41

The problem is that patients erroneously determined intraoperatively to have benign disease based on frozen section are unlikely to be adequately staged. In light of the inherent inaccuracy associated with frozen section, surgeons should consider staging patients with suspicious ovarian masses even if the interoperative diagnosis is benign. Moreover, surgeons should discuss intraoperative diagnostic limitations with their patients before surgery, irrespective of approach.

LAPAROSCOPY APPROACH FOR OVARIAN MASSES

Laparoscopic management of properly selected ovarian masses has become a standard part of modern obstetrics and gynecology.3 In one study of 396 women who underwent laparoscopy for a low-risk adnexal mass, only 2% of patients were ultimately found to have a malignancy.3 This low rate is related both to a low prevalence of malignancy among women with ovarian cysts in a general population and the efficacy of preoperative diagnostic testing. Because the possibility of a malignancy can never be eliminated preoperatively in patients with an ovarian mass, consideration should be given to obtaining consent for an open staging procedure in patients with a suspicious mass.

Laparoscopic Oophorectomy

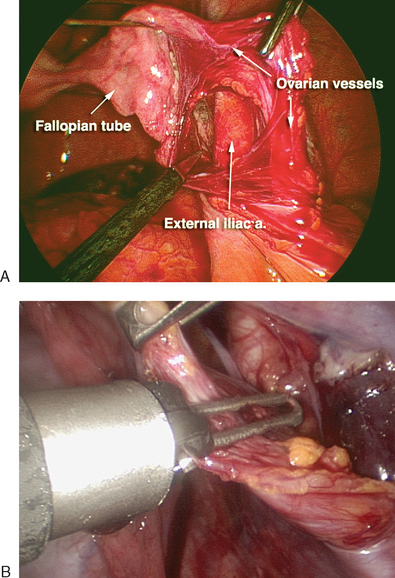

The first step in a laparoscopic oophorectomy is to identify the ureter. If the ureter can be clearly identified transperitoneally by its peristalsis and found to be safely beneath the level of the infundibulopelvic ligament, oophorectomy can be performed without opening the pelvic sidewall peritoneum. However, in cases where the ureter cannot be seen because of obesity, adhesions, or thickened peritoneum, the pelvic sidewall peritoneum should be opened. The infundibulopelvic ligament is put on tension and the peritoneum is opened to identify the ureter. The ovarian vessels are skeletonized and occluded using one of a variety of techniques: bipolar cautery, ultrasonic scalpel, a stapling device, or an endoligature (Fig. 50-2). Careful dissection using scissors or one of these power sources is then used to isolate and occlude the utero-ovarian ligament, thereby separating the ovary and tube from their attachments. The dissection bed should be inspected for hemostasis before removal of the ovary from the peritoneal cavity. At the conclusion of laparoscopy, the hemostasis of all vascular pedicles should be reevaluated as the intra-abdominal insufflation pressure is decreased.

Laparoscopic Ovarian Cystectomy

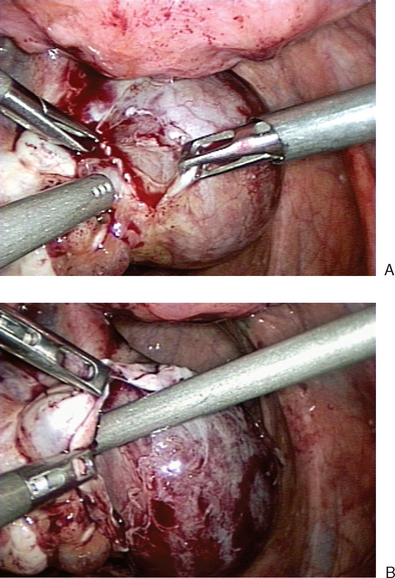

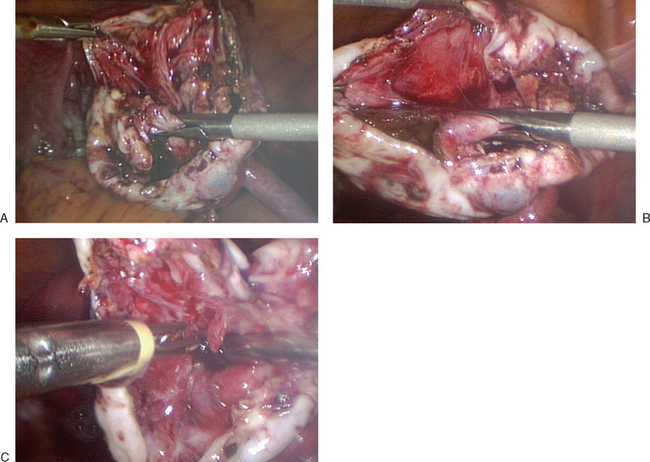

Once a defect is made, the ovarian tissue is bluntly separated from the cyst wall (Fig. 50-3A). The ovarian cortex is held with a grasper and gently peeled away from the underlying cyst (see Fig. 50-3B). This can be facilitated with aid of water dissection from the laparoscopic suction–irrigator. In areas where connections between the cortex and cyst wall do not separate easily, sharp dissection should be used to avoid cyst rupture and spill.

Removal of the Ovary or Cyst from the Peritoneal Cavity

Once the ovary or a cyst has been excised, the next challenge is to remove the specimen from the peritoneal cavity without spilling any cyst fluid into the peritoneal cavity. The ideal approach is to place the entire specimen intact into a retrieval bag for extraction.

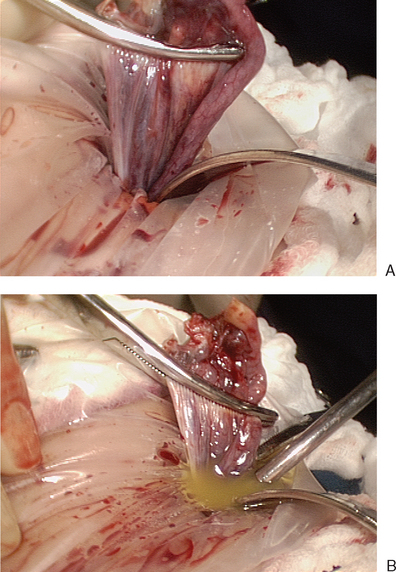

Cyst Aspiration and Morcellation in the Bag

After the specimen is placed into the retrieval bag, the opening of the bag is drawn up into one of the port sleeves. A 10-mm suprapubic or lateral port is usually used, but the umbilical port can also be used if the laparoscope is first placed through an alternative port. The selected incision is encircled with absorbent material to prevent inadvertent fluid contamination of the subcutaneous tissue during specimen extraction. The port sleeve containing the bag opening is removed from the abdominal wall, thus delivering the bag opening through the trocar incision (Figure 50-4).

Large Cysts

Intraperitoneal aspiration of a large ovarian cyst can be performed with either a laparoscopic aspiration needle or the suction– irrigation cannulae placed directly through the abdominal wall. Intraperitoneal spillage can be minimized (but not completely prevented) by placing a pursestring suture around the aspiration site before puncture or by placing an endoligature over the drainage site after cyst decompression. After the ovarian cyst has been decompressed, it can be removed from the abdomen.

Laparoscopic Endometrioma Resection

The edge of the cyst wall is separated from the ovarian tissue and is stripped using a combination of blunt and sharp dissection (Fig. 50-5A and B). Bleeding is common from the dissection bed, and bipolar cautery can be used to cauterize bleeding sites (see Fig. 50-5C). Excessive use of cautery can cause ovarian damage. The cyst wall is then placed in an endoscopic retrieval bag and extracted through a port incision.

CONCLUSION

1 Majeed AW, Troy G, Nicholl JP, et al. Randomised, prospective, single-blind comparison of laparoscopic versus small-incision cholecystectomy. Lancet. 1996;347:989-994.

2 Guerriero S, Alcazar JL, Ajossa S, et al. Comparison of conventional color Doppler imaging and power Doppler imaging for the diagnosis of ovarian cancer: Results of a European study. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;83:299-304.

3 Havrilesky LJ, Peterson BL, Dryden DK, et al. Predictors of clinical outcomes in the laparoscopic management of adnexal masses. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:243-251.

4 Attaran M, Falcone T, Goldberg J. Endometriosis: Still tough to diagnose and treat. Cleve Clin J Med. 2002;69:647-653.

5 Norris HJ, Jensen RD. Relative frequency of ovarian neoplasms in children and adolescents. Cancer. 1972;30:713-719.

6 Koonings PP, Campbell K, Mishell DRJr., Grimes DA. Relative frequency of primary ovarian neoplasms: A 10-year review. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;74:921-926.

7 Huss M, Lafay-Pillet MC, Lecuru F, et al. [Granulomatous peritonitis after laparoscopic surgery of an ovarian dermoid cyst. Diagnosis, management, prevention: A case report]. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 1996;25:365-372.

8 Chen L, Nelson SD, Berek JS. Recurrent mature cystic teratoma presenting as a perihepatic mass. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94:856.

9 Lin P, Falcone T, Tulandi T. Excision of ovarian dermoid cyst by laparoscopy and by laparotomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173:769-771.

10 Nezhat CR, Kalyoncu S, Nezhat CH, et al. Laparoscopic management of ovarian dermoid cysts: Ten years’ experience. JSLS. 1999;3:179-184.

11 Templeman CL, Hertweck SP, Scheetz JP, et al. The management of mature cystic teratomas in children and adolescents: A retrospective analysis. Hum Reprod. 2000;15:2669-2672.

12 Padilla LA, Radosevich DM, Milad MP. Accuracy of the pelvic examination in detecting adnexal masses. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:593-598.

13 Schutter EM, Kenemans P, Sohn C, et al. Diagnostic value of pelvic examination, ultrasound, and serum CA 125 in postmenopausal women with a pelvic mass. An international multicenter study. Cancer. 1994;74:1398-1406.

14 Guerriero S, Mallarini G, Ajossa S, et al. Transvaginal ultrasound and computed tomography combined with clinical parameters and CA-125 determinations in the differential diagnosis of persistent ovarian cysts in premenopausal women. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1997;9:339-343.

15 Andersen ES, Knudsen A, Rix P, Johansen B. Risk of malignancy index in the preoperative evaluation of patients with adnexal masses. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;90:109-112.

16 Finkler NJ, Benacerraf B, Lavin PT, et al. Comparison of serum CA 125, clinical impression, and ultrasound in the preoperative evaluation of ovarian masses. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;72:659-664.

17 Granberg S, Wikland M, Jansson I. Macroscopic characterization of ovarian tumors and the relation to the histological diagnosis: Criteria to be used for ultrasound evaluation. Gynecol Oncol. 1989;35:139-144.

18 Guerriero S, Ajossa S, Garau N, et al. Ultrasonography and color Doppler-based triage for adnexal masses to provide the most appropriate surgical approach. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:401-406.

19 Davies AP, Jacobs I, Woolas R, et al. The adnexal mass: Benign or malignant? Evaluation of a risk of malignancy index. BJOG. 1993;100:927-931.

20 Strigini FA, Gadducci A, Del Bravo B, et al. Differential diagnosis of adnexal masses with transvaginal sonography, color flow imaging, and serum CA 125 assay in pre- and postmenopausal women. Gynecol Oncol. 1996;61:68-72.

21 Predanic M, Vlahos N, Pennisi JA, et al. Color and pulsed Doppler sonography, gray-scale imaging, and serum CA 125 in the assessment of adnexal disease. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88:283-288.

22 Roman LD, Muderspach LI, Stein SM, et al. Pelvic examination, tumor marker level, and gray-scale and Doppler sonography in the prediction of pelvic cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:493-500.

23 Alcazar JL, Jurado M. Using a logistic model to predict malignancy of adnexal masses based on menopausal status, ultrasound morphology, and color Doppler findings. Gynecol Oncol. 1998;69:146-150.

24 Guerriero S, Ajossa S, Risalvato A, et al. Diagnosis of adnexal malignancies by using color Doppler energy imaging as a secondary test in persistent masses. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1998;11:277-282.

25 Alcazar JL, Errasti T, Zornoza A, et al. Transvaginal color Doppler ultrasonography and CA-125 in suspicious adnexal masses. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1999;66:255-261.

26 Kobal B, Rakar S, Ribic-Pucelj M, et al. Pretreatment evaluation of adnexal tumors predicting ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 1999;9:481-486.

27 Mol BW, Boll D, De Kanter M, et al. Distinguishing the benign and malignant adnexal mass: An external validation of prognostic models. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;80:162-167.

28 Mancuso A, De Vivo A, Triolo O, Irato S. The role of transvaginal ultrasonography and serum CA 125 assay combined with age and hormonal state in the differential diagnosis of pelvic masses. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2004;25:207-210.

29 ACOG. The role of the generalist obstetrician-gynecologist in the early detection of ovarian cancer. ACOG Committee Opinion no. 280, December 2002. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:1413-1416.

30 Im SS, Gordon AN, Buttin BM, et al. Validation of referral guidelines for women with pelvic masses. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:35-41.

31 Gal D, Lind L, Lovecchio JL, Kohn N. Comparative study of laparoscopy vs. laparotomy for adnexal surgery: Efficacy, safety, and cyst rupture. J Gynecol Surg. 1995;11:153-158.

32 Vergote I, De Brabanter J, Fyles A, et al. Prognostic importance of degree of differentiation and cyst rupture in stage I invasive epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Lancet. 2001;357:176-182.

33 Sainz de la Cuesta R, Goff BA, Fuller AFJr, et al. Prognostic importance of intraoperative rupture of malignant ovarian epithelial neoplasms. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84:1-7.

34 Kodama S, Tanaka K, Tokunaga A, et al. Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors in patients with ovarian cancer stage I and II. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1997;56:147-153.

35 Dembo AJ, Davy M, Stenwig AE, et al. Prognostic factors in patients with stage I epithelial ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:263-273.

36 Ahmed FY, Wiltshaw E, A’Hern RP, et al. Natural history and prognosis of untreated stage I epithelial ovarian carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:2968-2975.

37 Sjovall K, Nilsson B, Einhorn N. Different types of rupture of the tumor capsule and the impact on survival in early ovarian carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 1994;4:333-336.

38 Mizuno M, Kikkawa F, Shibata K, et al. Long-term prognosis of stage I ovarian carcinoma. Prognostic importance of intraoperative rupture. Oncology. 2003;65:29-36.

39 Young RC, Decker DG, Wharton JT, et al. Staging laparotomy in early ovarian cancer. JAMA. 1983;250:3072-3076.

40 Rose PG, Rubin RB, Nelson BE, et al. Accuracy of frozen-section (intraoperative consultation) diagnosis of ovarian tumors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171:823-826.

41 Boriboonhirunsarn D, Sermboon A. Accuracy of frozen section in the diagnosis of malignant ovarian tumor. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2004;30:394-399.

42 Cotran RS, Kumar V, Collins T, Robbins SL. Robbins Pathologic Basis of Disease. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company, 1999.