CHAPTER 145 Juvenile Nasal Angiofibroma

Juvenile nasal angiofibroma (JNA) is a rare sinonasal tumor that is found almost exclusively in adolescent and young adult males. Frequently, the term juvenile is not included in the name of this tumor because this lesion may occur in adults occasionally, as well as in adolescents. In addition, the term nasopharyngeal is often used instead of “nasal” because angiofibromas that occur elsewhere are a somewhat different lesion with a different history and biologic behavior. Thus, JNA and nasopharyngeal angiofibroma are names for the same lesion. It accounts for less than 0.5% of head and neck neoplasms and is the most common benign tumor of the nasopharynx.1 In a recent national retrospective cohort study conducted over a 22-year period, there were 43 cases of JNA in Denmark for an incidence rate of 0.4 case per million inhabitants per year and 3.7 cases per million males (10 to 24 years old) per year.2 The tumor is thought to arise from the pterygomaxillary fossa in the recess behind the sphenopalatine ganglion at the exit aperture of the pterygoid canal.3 This spot is the trifurcation of the sphenoid process of the palatine bone, the horizontal ala of the vomer, and the root of the pterygoid process of the sphenoid. Histologic serial sections of fetal heads have confirmed the presence of large endothelial-lined spaces in the region of the sphenopalatine foramen and base of the pterygoid plates in both males and females. It is thought that the tumor arises as a connective tissue response to a hamartomatous ectopic nidus of vascular tissue. Although benign histologically, JNAs may be life-threatening because of bleeding and intracranial extension.

Clinical Findings

The tumor typically occurs in males 14 to 25 years of age, although there are reports of it occurring in elderly women.4,5 The most common initial symptoms are epistaxis and unilateral nasal obstruction. The occurrence of other symptoms is primarily dependent on the direction and extent of regional spread. The tumor may spread to the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses, orbit, and intracranial cavity. Symptoms may include proptosis, diplopia, pain and swelling in the cheek, headache, sinusitis, and hearing loss. In comparison, extranasopharyngeal angiofibromas are extremely rare; may arise from sites other than the nasopharynx, most commonly the maxilla but also the ethmoid, nasal cavity, and septum; can affect adult women; are less vascular; and usually have local and less aggressive growth.6

Imaging and Histopathology

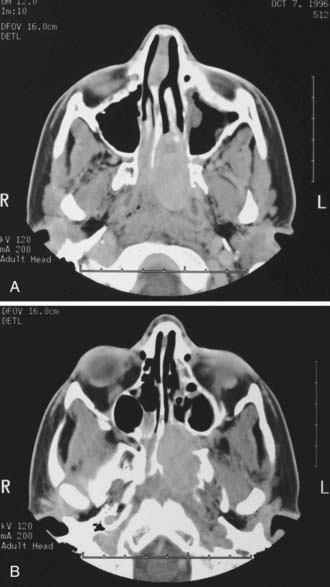

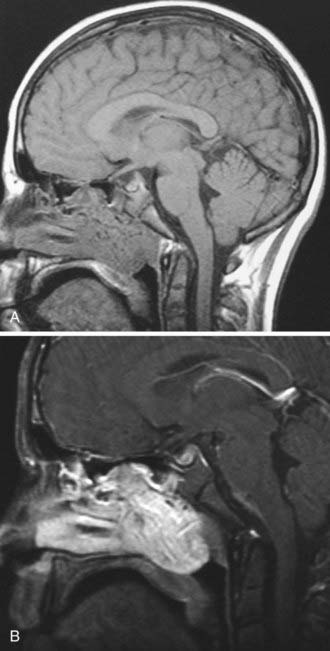

Historically, the most suggestive finding was the antral or Holman-Miller sign: anterior bowing of the posterior wall of the maxillary sinus observed on a submentovertical plain skull radiograph (Waters view). All patients should undergo computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). CT is the preferred modality for the initial evaluation because it precisely defines the bony architecture of the sinonasal tract and skull base and outlines the orbital involvement (Fig. 145-1). MRI better defines the soft tissue planes, especially when the tumor extends beyond the nasopharynx into the infratemporal fossa and when intracranial spread has occurred (Fig. 145-2). Two constant features include (1) a mass in the posterior nasal cavity and pterygopalatine fossa and (2) erosion of bone behind the sphenopalatine foramen extending to the upper medial pterygoid plate.7 The vascular nature of JNAs is seen by the presence of flow voids on MRI. The tumor avidly enhances, and intracranial extensions may be extradural or intradural. The tumor may spread through paths of least resistance. In general, there are five directions of spread: (1) anteriorly to the nasal cavity and sinuses; (2) posteriorly to the pterygoid fossa; (3) laterally to the pterygopalatine (pterygomaxillary) fossa and infratemporal fossa; (4) superiorly into the sphenoid with possible further erosion through the posterior wall to the cavernous sinus; and (5) medially into the orbit through the inferior orbital fissure, backward toward the orbital apex, extension out through the superior orbital fissure, and extension into the cavernous sinus.

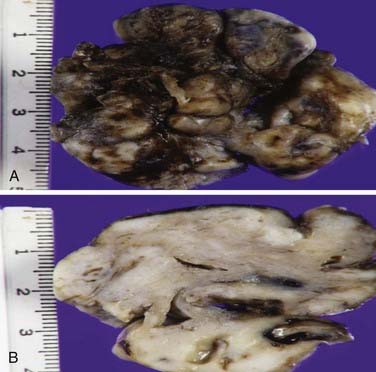

Grossly, this lesion is typically nonpedunculated, well circumscribed, often multilobular, firm and rubbery, and variably pale tan-gray to maroon red (Fig. 145-3A). Focal surface mucosal ulceration is occasionally seen in this otherwise smooth and shiny surfaced lesion. Cut sections are solid to often spongy, depending on vascularity (Fig. 145-3B).

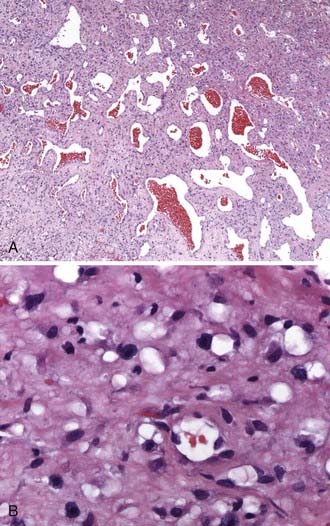

Microscopically, nasal angiofibroma is typically thinly encapsulated with a respiratory-type mucosal lining. Underlying this lining is a histologically benign component with relatively low to moderate cellularity (Fig. 145-4A). Its associated fibrovascular collagenous connective tissue stroma is often superficially loose but becomes dense with increasing depth from the surface mucosa. The density, prominence, and size of the irregular, variably thin-walled vascular elements vary somewhat. Vessels have a simple endothelial lining, generally lack elastin and much mural smooth muscle (especially in the central depths of the tumor, but this also holds true for most of the superficial vessels), vary in shape from staghorn to stellate to slit-like, and are occasionally even inconspicuous (secondary to compression by surrounding stroma). Some, especially more superficial vessels, have thicker walls with more smooth muscle and an arteriolar appearance. The vascular component appears to be most prominent during the early growth phase of tumor development. The cytologically innocuous-appearing stromal fibroblasts and occasional myofibroblasts may demonstrate a perivascular proclivity. These cells vary from spindle to ovoid to stellate appearing. Small nucleoli are often seen in these cells. Foci of myxoid or hyalinizing degenerative change may be observed. Mitotic activity is generally rare, infrequent, or inconspicuous. Mast cells are often plentiful, but inflammatory infiltrates are otherwise usually minor, unless the lesion is recurrent or has been subjected to ancillary therapies (Fig. 145-4B). Obviously, this highly consistent and characteristic histopathology may be altered by preoperative embolization therapy; secondary changes such as a foreign body reaction, tumor necrosis, increased inflammation, and increased nuclear atypia may then be observed. Likewise, some such features (i.e., increased inflammation and nuclear atypia) may be more prominent in recurrent lesions.

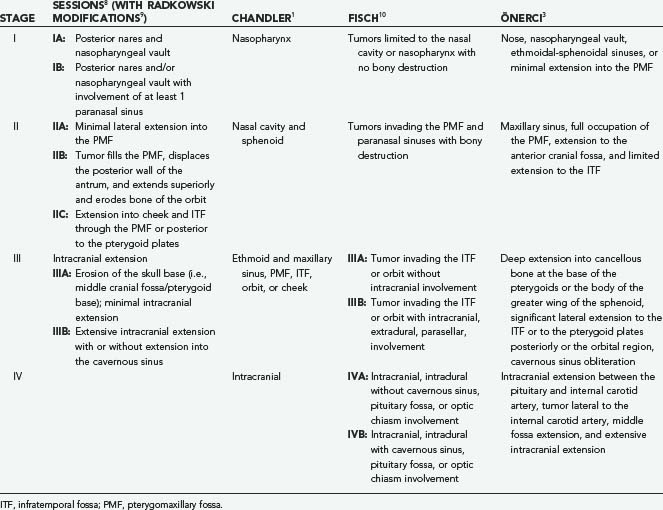

Staging

Numerous staging systems based on tumor extent and spread have been proposed and help facilitate decision making regarding surgical approaches and prognosis (Table 145-1).1,8–11 The Sessions classification was the first, with other authors making modifications to it. For example, Radkowski made a minor change to stage IIC to account for extension posterior to the pterygoid plates in the infratemporal fossa.9 Tumors in this location are in close proximity to the foramen lacerum and thus the carotid artery and make complete surgical excision more difficult. Radkowski also differentiated between minimal (IIIA) and extensive (IIIB) intracranial involvement. Önerci and colleagues developed the most recent classification system to take into account improved radiographic imaging, embolization, and surgical methods, particularly endoscopic techniques.11

Management

Embolization

Diagnostic angiography and embolization should be completed in a single procedure whenever possible. The vast majority of studies have found preoperative embolization to be of benefit in reducing intraoperative blood loss.9,12,13 However, some believe that for Sessions IIB or lower lesions that can be resected with a transnasal, endoscopic approach, there may be no need for preoperative embolization.14,15 Embolization is not without risk. Bradycardia can occasionally occur after injection of the maxillary and ascending pharyngeal arteries; it is usually transient but may require atropine. Other more serious complications include ischemic cranial nerve palsies (e.g., facial nerve), intracranial embolization via external-internal carotid anastomoses, and visual loss.11,16 Furthermore, embolization must be performed selectively to avoid devascularization of structures such as the maxilla if a Le Fort I approach is planned or the temporalis muscle if it is needed for skull base reconstruction. Surgery should commence within 24 to 48 hours of embolization because of the propensity of the tumor for rapid revascularization.

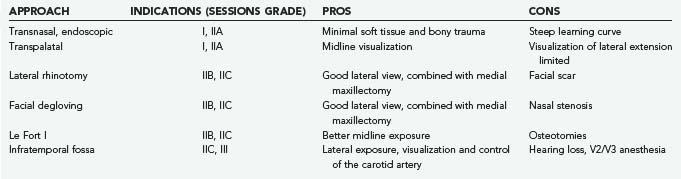

Surgery—Overview

Surgery is the primary treatment modality in the vast majority of patients with de novo and recurrent disease. In general, the surgical approach depends on the tumor stage and the experience of the surgeon. Surgical approaches can be divided into inferior, anterior, and lateral.17 Inferior approaches include the transpalatal and the transoral/transpharyngeal approach with or without splitting of the soft palate. Anterior approaches access the nasal cavity and include open (lateral rhinotomy, midfacial degloving, transfacial approaches) and endoscopic techniques. The infratemporal fossa may be approached laterally through a preauricular subtemporal route. Grant and colleagues summarized the advantages and disadvantages of the most common approaches (Table 145-2).18 Approaches may be combined, depending on the extent of the tumor.

Endoscopic Surgery

The endoscopic technique has become the favored approach for lesions confined to the nasopharynx with minimal lateral extension. Excellent results have been achieved by experienced surgeons. When compared with traditional open techniques, this minimally invasive approach appears to be associated with a lower risk for surgical morbidity, shorter hospital stay, less intraoperative blood loss, and a very low risk for recurrence, between 0% and 7%.19–21 Andrade and associates successfully resected stage I and stage II tumors in 42 patients without preoperative embolization and showed no residual or recurrent disease with follow-up ranging from 5 to 42 months.14 Gupta and coworkers used this endonasal/endoscopic technique in 28 patients with de novo and recurrent disease. All patients had Sessions grade IIB or lower except 1 patient, and in this patient some residual disease was noted postoperatively. All the other patients had no evidence of recurrence at a minimal follow-up of 12 months.22 Similar results have been reported by other authors.15,23–25

Over the past 10 to 15 years, more surgeons have become trained and comfortable with endoscopic techniques, and consequently, the limits of this approach are continuously being challenged and the techniques refined.26 There have been numerous reports of successful extirpation of stage IIIA tumors.27–31 Roger and coauthors reported on 20 patients, including 9 with Radkowski stage IIIA tumors. They were able to resect tumors located in the sphenoid sinus, pterygomaxillary fossa, or infratemporal fossa but did not attempt resection of tumors invading the skull base. At a mean follow-up of 22 months, no patients had recurrent disease and 2 patients had small, asymptomatic residual disease.30 Önerci and coworkers reported on 12 patients, 8 of whom had Radkowski stage IIC and 4 had minimal intracranial disease (IIIA).29 All IIC patients underwent complete excision with no recurrence during the follow-up period. Two stage IIIA patients did have small residual disease in the cavernous sinus that has been stable for 2 years. Naraghi and Kashfi used both transnasal and transoral routes with 0- and 30-degree endoscopes, which provided two-sided access to stage IA-IIB tumors.32 Use of the harmonic scalpel33 and lasers34,35 has aided the surgeon in the endoscopic approach.

Open Surgery—Inferior and Anterior Approaches

Despite the excitement generated for the endoscopic approach, traditional open approaches still have a role, usually with more extensive tumors. The transpalatal approach has been the classic open approach for stage IA-IIA disease.36 However, given the limited lateral exposure and morbidity such as palatal necrosis, dental hypoesthesia, oronasal fistula, and eustachian tube dysfunction, the endoscopic approach has supplanted the transpalatal approach for many surgeons. Transfacial approaches are popular with stage IIA/IIB/IIIA disease. Such approaches include a sublabial Caldwell-Luc operation that may be combined with a midface degloving approach to avoid a facial scar such as with a lateral rhinotomy. Several authors have used the midface degloving approach even with significant tumor burden in the infratemporal fossa.23,37–39 El-Banahawy and associates described an endoscopically assisted midface degloving approach. Fifteen patients with Fisch stage III disease were operated on, and small recurrences were observed in two patients on routine endoscopic examination.39 The recurrences were successfully removed endoscopically with no further sequelae. In fact, Danesi and colleagues thought that MRI may overcall intracranial involvement, that tumor more commonly displaces the dura rather than adhering to or perforating it, that the transfacial degloving approach with its wide surgical field allows the surgeon excellent access to the infratemporal fossa, and that a lateral approach is rarely needed.37,38 Complications of the degloving approach include nasal stenosis and drooping of the nasal tip.18 The lateral rhinotomy provides broad exposure and lateral access, but drawbacks are the visible scar and possible injury to the lacrimal duct, inferior orbital nerve, and inferior eyelid.

The Le Fort I osteotomy is a well-described approach for stage II tumors.36,40 It provides exposure of the anterior nasal cavity, pterygopalatine fossa, and nasopharynx. de Mello-Filho and colleagues used this approach in 19 patients with only one complication, that being malocclusion.40 Over a follow-up period that ranged from 1 to 19 years (mean of 10 years), no recurrence was detected in any patient. A medial maxillotomy swing-type approach is done through a unilateral Le Fort I osteotomy.41 Accurate reduction and fixation of the maxilla are achieved by using miniplates fitted before the osteotomy is performed. Even a minor malocclusion is a significant bother to the patient. Furthermore, the dental hypoesthesia that occurs as a result of the Le Fort osteotomy usually does recover but takes 9 to 12 months. It should not be performed in young patients to avoid issues with impaired midface growth.

Intracranial involvement occurs in 10% to 30% of cases. A lateral skull base approach can be used when there is significant tumor extension into the infratemporal fossa with or without intracranial extension into the middle fossa.10,23,42–44 Tumor within the infratemporal fossa may spread into the middle fossa by way of the foramina lacerum and ovale. The infratemporal approach is quite complex but can be summarized in the following steps: skin incision, temporalis elevation, zygomatic ostectomy, mandibular condylectomy, and middle fossa craniotomy. The craniotomy incorporates a superior portion over the greater sphenoid wing and squamosal temporal bone and an inferior portion that ends at the foramina spinosum and ovale. Bales and coworkers combined the infratemporal fossa approach with a transfacial degloving approach in five patients with stage IIIB disease.45 As stated previously, the temporalis muscle may serve as a major vascularized barrier between the middle cranial fossa and the upper aerodigestive tract. As such, its inferior blood supply from deep branches arising from the internal maxillary artery need to be preserved during preoperative embolization. Complications with this skull base approach include hearing loss, cranial neuropathies such as the facial and trigeminal (V2 and V3) neuropathy, temporomandibular joint dysfunction, cerebrospinal leak, and meningitis.

Residual and recurrent disease is directly related to the extent of the tumor, the approach used, and the experience of the surgical team. Recurrence rates vary and range from 0% to 28%.2,14,15,20,37,45,46 Surgery is usually the mainstay for treatment of recurrences that are resectable. All patients should undergo MRI or CT, or both, postoperatively to evaluate for residual disease. Kania and colleagues found that postoperative contrast-enhanced CT had a sensitivity of 75%, a specificity of 83%, a positive predictive value of 75%, and a negative predictive value of 83% for detection of residual disease.47 Several anatomic areas have been cited as being at high risk for residual tumor and thus recurrence. These areas include extension into cancellous bone at the base of the pterygoid plates, body and greater wing of the sphenoid,3,7 posterior to the pterygoid plates and into the pterygoid muscles,3,9 middle fossa, and cavernous sinus.48,49 However, small areas of residual disease should be monitored by serial imaging because tumor remnants often remain stable or may regress as the patient emerges from puberty.

Radiation Therapy

Conventional external beam radiotherapy is reserved for patients who are poor surgical candidates, refuse surgery, or have a significant intracranial tumor burden that cannot be fully resected or in whom the associated morbidity is unacceptably high. The recommended dose ranges from 35 to 45 Gy. McGahan and associates found a high incidence of tumor recurrence in patients who received 3200 cGy in 200-cGy fractions and thus recommended a total dose of 40 Gy or greater.50 Conversely, high local control and very low recurrence rates have been reported with total doses between 30 and 36 Gy.51 In a series from the University of California at Los Angeles Medical Center, 27 patients received radiation as the primary treatment with doses ranging from 3000 to 5500 cGy.52 Recurrences developed in 4 (15%) of these patients over time periods ranging from 2 to 5 years, and radiation-induced complications occurred in 4 patients: growth retardation, panhypopituitarism, temporal lobe necrosis, cataracts, and radiation-induced keratopathy. Although symptomatic improvement occurs quite rapidly, regression of the tumor after radiation therapy can take on average a year to occur, and patients who continue to have tumor more than 2 years after radiation therapy may have an increased risk for recurrence.53 Experience with stereotactic radiosurgery is limited, but there are reports of using it as an adjuvant treatment to surgery for residual disease in high-risk areas such as the cavernous sinus.54,55 The dose delivered is typically 14 to 16 Gy, which corresponds to the 50% isodose line.

Andrade Andrade NA, Pinto JA, Nobrega Mde O, et al. Exclusively endoscopic surgery for juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;137:492-496.

Danesi Danesi G, Panciera DT, Harvey RJ, et al. Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: evaluation and surgical management of advanced disease. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;138:581-586.

Glad Glad H, Vainer B, Buchwald C, et al. Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibromas in Denmark 1981-2003: diagnosis, incidence, and treatment. Acta Otolaryngol. 2007;127:292-299.

Roche Roche PH, Paris J, Regis J, et al. Management of invasive juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibromas: the role of a multimodality approach. Neurosurgery. 2007;61:768-777.

1 Chandler JR, Goulding R, Moskowitz L, et al. Nasopharyngeal angiofibromas: staging and management. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1984;93:322-329.

2 Glad H, Vainer B, Buchwald C, et al. Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibromas in Denmark 1981-2003: diagnosis, incidence, and treatment. Acta Otolaryngol. 2007;127:292-299.

3 Onerci M, Ogretmenoglu O, Yucel T. Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: a revised staging system. Rhinology. 2006;44:39-45.

4 Patrocinio JA, Patrocinio LG, Borba BH, et al. Nasopharyngeal angiofibroma in an elderly woman. Am J Otolaryngol. 2005;26:198-200.

5 Szymanska A, Korobowicz E, Golabek W. A rare case of nasopharyngeal angiofibroma in an elderly female. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;263:657-660.

6 Windfuhr JP, Remmert S. Extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma: etiology, incidence and management. Acta Otolaryngol. 2004;124:880-889.

7 Lloyd G, Howard D, Lund VJ, et al. Imaging for juvenile angiofibroma. J Laryngol Otol. 2000;114:727-730.

8 Bryan RN, Sessions RB, Horowitz BL. Radiographic management of juvenile angiofibromas. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1981;2:157-166.

9 Radkowski D, McGill T, Healy GB, et al. Angiofibroma. Changes in staging and treatment. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;122:122-129.

10 Fisch U. The infratemporal fossa approach for nasopharyngeal tumors. Laryngoscope. 1983;93:36-44.

11 Önerci M, Gumus K, Cil B, et al. A rare complication of embolization in juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;69:423-428.

12 Li JR, Qian J, Shan XZ, et al. Evaluation of the effectiveness of preoperative embolization in surgery for nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1998;255:430-432.

13 Moulin G, Chagnaud C, Gras R, et al. Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: comparison of blood loss during removal in embolized group versus nonembolized group. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1995;18:158-161.

14 Andrade NA, Pinto JA, Nobrega Mde O, et al. Exclusively endoscopic surgery for juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;137:492-496.

15 Borghei P, Baradaranfar MH, Borghei SH, et al. Transnasal endoscopic resection of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma without preoperative embolization. Ear Nose Throat J. 2006;85:740-743. 746

16 Ikram M, Khan K, Murad M, et al. Facial nerve palsy unusual complication of percutaneous angiography and embolization for juvenile angiofibroma. J Pak Med Assoc. 1999;49:201-202.

17 Paris J, Guelfucci B, Moulin G, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2001;258:120-124.

18 Grant GA, Ellenbogen RG, Manning SC. Diagnosis and management of juvenile angiofibroma. In: Winn HR, editor. Youmans Neurological Surgery, Vol 1. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 2004:1351-1359.

19 Enepekides DJ. Recent advances in the treatment of juvenile angiofibroma. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;12:495-499.

20 Pryor SG, Moore EJ, Kasperbauer JL. Endoscopic versus traditional approaches for excision of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:1201-1207.

21 Yiotakis I, Eleftheriadou A, Davilis D, et al. Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma stages I and II: a comparative study of surgical approaches. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;72:793-800.

22 Gupta AK, Rajiniganth MG, Gupta AK. Endoscopic approach to juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: our experience at a tertiary care centre. J Laryngol Otol. 2008;122:1185-1189.

23 Cansiz H, Guvenc MG, Sekercioglu N. Surgical approaches to juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2006;34:3-8.

24 Nicolai P, Berlucchi M, Tomenzoli D, et al. Endoscopic surgery for juvenile angiofibroma: when and how. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:775-782.

25 Scholtz AW, Appenroth E, Kammen-Jolly K, et al. Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: management and therapy. Laryngoscope. 2001;111:681-687.

26 Mann WJ, Jecker P, Amedee RG. Juvenile angiofibromas: changing surgical concept over the last 20 years. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:291-293.

27 Douglas R, Wormald PJ. Endoscopic surgery for juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: where are the limits? Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;14:1-5.

28 Hofmann T, Bernal-Sprekelsen M, Koele W, et al. Endoscopic resection of juvenile angiofibromas—long term results. Rhinology. 2005;43:282-289.

29 Onerci TM, Yucel OT, Ogretmenoglu O. Endoscopic surgery in treatment of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2003;67:1219-1225.

30 Roger G, Tran Ba Huy P, Froehlich P, et al. Exclusively endoscopic removal of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: trends and limits. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:928-935.

31 Tosun F, Ozer C, Gerek M, et al. Surgical approaches for nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: comparative analysis and current trends. J Craniofac Surg. 2006;17:15-20.

32 Naraghi M, Kashfi A. Endoscopic resection of nasopharyngeal angiofibromas by combined transnasal and transoral routes. Am J Otolaryngol. 2003;24:149-154.

33 Chen MK, Tsai YL, Lee KW, et al. Strictly endoscopic and harmonic scalpel–assisted surgery of nasopharyngeal angiofibromas: eligible for advanced stage tumors. Acta Otolaryngol. 2006;126:1321-1325.

34 Hazarika P, Nayak DR, Balakrishnan R, et al. Endoscopic and KTP laser–assisted surgery for juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Am J Otolaryngol. 2002;23:282-286.

35 Mair EA, Battiata A, Casler JD. Endoscopic laser-assisted excision of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibromas. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:454-459.

36 Hosseini SM, Borghei P, Borghei SH, et al. Angiofibroma: an outcome review of conventional surgical approaches. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;262:807-812.

37 Danesi G, Panciera DT, Harvey RJ, et al. Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: evaluation and surgical management of advanced disease. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;138:581-586.

38 Danesi G, Panizza B, Mazzoni A, et al. Anterior approaches in juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibromas with intracranial extension. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;122:277-283.

39 El-Banhawy OA, Shehab El-Dien Ael H, Amer T. Endoscopic-assisted midfacial degloving approach for type III juvenile angiofibroma. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;68:21-28.

40 de Mello-Filho FV, De Freitas LC, Dos Santos AC, et al. Resection of juvenile angiofibroma using the Le Fort I approach. Am J Otolaryngol. 2004;25:157-161.

41 Dubey SP, Molumi CP. Critical look at the surgical approaches of nasopharyngeal angiofibroma excision and “total maxillary swing” as a possible alternative. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2007;116:723-730.

42 Browne JD, Jacob SL. Temporal approach for resection of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibromas. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:1287-1293.

43 Choi JY, Lee WS. Curative surgery for recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma via the infratemporal fossa approach. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;131:213-216.

44 Donald PJ, Enepikedes D, Boggan J. Giant juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: management by skull-base surgery. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:882-886.

45 Bales C, Kotapka M, Loevner LA, et al. Craniofacial resection of advanced juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:1071-1078.

46 Herman P, Lot G, Chapot R, et al. Long-term follow-up of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibromas: analysis of recurrences. Laryngoscope. 1999;109:140-147.

47 Kania RE, Sauvaget E, Guichard JP, et al. Early postoperative CT scanning for juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: detection of residual disease. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26:82-88.

48 Tyagi I, Syal R, Goyal A. Recurrent and residual juvenile angiofibromas. J Laryngol Otol. 2007;121:460-467.

49 Tyagi I, Syal R, Goyal A. Staging and surgical approaches in large juvenile angiofibroma—study of 95 cases. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;70:1619-1627.

50 McGahan RA, Durrance FY, Parke RBJr, et al. The treatment of advanced juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1989;17:1067-1072.

51 McAfee WJ, Morris CG, Amdur RJ, et al. Definitive radiotherapy for juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2006;29:168-170.

52 Lee JT, Chen P, Safa A, et al. The role of radiation in the treatment of advanced juvenile angiofibroma. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:1213-1220.

53 Reddy KA, Mendenhall WM, Amdur RJ, et al. Long-term results of radiation therapy for juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Am J Otolaryngol. 2001;22:172-175.

54 Dare AO, Gibbons KJ, Proulx GM, et al. Resection followed by radiosurgery for advanced juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: report of two cases. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:1207-1211.

55 Roche PH, Paris J, Regis J, et al. Management of invasive juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibromas: the role of a multimodality approach. Neurosurgery. 2007;61:768-777.