Chapter 153 Juvenile Dermatomyositis

Clinical Manifestations

Rash develops as the first symptom in 50% of cases and appears concomitant with weakness only 25% of the time. Children often exhibit extreme photosensitivity to ultraviolet light exposure with generalized erythema in sun-exposed areas. If seen over the chest and neck, this erythema is known as the “shawl sign.” Erythema is also commonly seen over the knees and elbows. The characteristic heliotrope rash (Fig. 153-1) is a blue-violet discoloration of the eyelids that may be associated with periorbital edema. Facial erythema crossing the nasolabial folds is also common, in contrast to the malar rash without nasolabial involvement typical of systemic lupus erythematosus. Classic Gottron papules (Fig. 153-2) are bright pink or pale, shiny, thickened or atrophic plaques over the proximal interphalangeal joints and distal interphalangeal joints and occasionally on the knees, elbows, small joints of the toes, and ankle malleoli. The rash of JDM is sometimes mistaken for eczema or psoriasis. Rarely, a thickened erythematous and scaly rash develops in children over the palms (known as mechanic’s hands) and soles along the flexor tendons, which is associated with anti-Jo-1 antibodies.

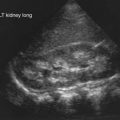

Evidence of small vessel inflammation is often visible in the nail folds and gums as individual capillary loops that are thickened, tortuous, or absent (Fig. 153-3). Telangiectasias may be visible to the naked eye but are more easily visualized under capillaroscopy or with use a magnifier such as an ophthalmoscope. Severe vascular inflammation causes cutaneous ulcers on toes, fingers, axillae, or epicanthal folds.

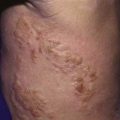

Lipodystrophy and calcinosis (Fig. 153-4) are thought to be associated with longstanding or undertreated disease. Dystrophic deposition of calcium phosphate, hydroxyapatite, or fluoroapatite crystals occurs in subcutaneous plaques or nodules, resulting in painful ulceration of the skin with extrusion of crystals or calcific liquid. Calcinosis is reported in up to 40% of children with JDM, but the prevalence is thought to be lower in children who are treated early and aggressively. In rare instances, an “exoskeleton” of calcium deposition forms, greatly limiting mobility. Lipodystrophy results in progressive loss of subcutaneous and visceral fat, typically over the face and upper body, and may be associated with a metabolic syndrome similar to polycystic ovarian syndrome with insulin resistance, hirsutism, acanthosis, hypertriglyceridemia, and abnormal glucose tolerance. Lipodystrophy may be generalized or localized.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of dermatomyositis requires the presence of characteristic rash as well as at least three signs of muscle inflammation and weakness (Table 153-1). Diagnostic criteria developed in 1975 predate the use of MRI and have not been validated in children. Diagnosis is often delayed because of the insidious nature of disease onset.

Table 153-1 DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR JUVENILE DERMATOMYOSITIS

| Classic rash |

Data from Bohan A, Peter JB: Polymyositis and dermatomyositis (second of two parts), N Engl J Med 292:403–407, 1975.

Laboratory Findings

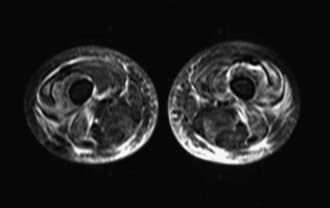

Radiographic studies aid both diagnosis and medical management. MRI using T2-weighted images and fat suppression (Fig. 153-5) identifies active sites of disease, reducing sampling error and increasing the sensitivity of muscle biopsy and electromyography, results of which are nondiagnostic in 20% of instances if the procedures are not directed by MRI. Extensive rash and abnormal MRI findings may be found despite normal serum levels of muscle-derived enzymes. Muscle biopsy often demonstrates evidence of disease activity and chronicity that is not suspected from the levels of the serum enzymes alone.

Bingham A, Mamyrova G, Rother KI. Predictors of acquired lipodystrophy in juvenile-onset dermatomyositis and a gradient of severity. Medicine (Baltimore). 2008;87:70-86.

Feldman BM, Rider LG, Reed AM, et al. Juvenile dermatomyositis and other idiopathic inflammatory myopathies of childhood. Lancet. 2008;371:2201-2212.

Griffin TA, Reed AM. Pathogenesis of myositis in children. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2007;19:487-491.

Gunawardena H, Betteridge ZE, McHugh NJ. Newly identified autoantibodies: relationship to idiopathic inflammatory myopathy subsets and pathogenesis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2008;20:675-680.

Klein R, Rosenbach M, Kim EJ, et al. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitor-associated dermatomyositis. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146(7):780-784.

Lopez de Padilla CM, Vallejo AN, McNallan KT, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells in inflamed muscle of patients with juvenile dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:1658-1668.

Mamyrova G, O’Hanlon TP, Sillers L, et al. Cytokine gene polymorphisms as risk and severity factors for juvenile dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:3941-3950.

Pachman LM, Lipton R, Ramsey-Goldman R, et al. History of infection before the onset of juvenile dermatomyositis: results from the National Institute of Arthritis Muscle and Skin Diseases Research Registry. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53:166-172.

Ravelli A, Trail L, Ferrari C, et al. Long-term outcome and prognostic factors of juvenile dermatomyositis: a multifunctional, multicenter study of 490 patients. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62:63-72.

Reed AM, McNallan K, Wettstein P, et al. Does HLA-dependent chimerism underlie the pathogenesis of juvenile dermatomyositis? J Immunol. 2004;172:5041-5046.

Rider LG, Miller FW. Deciphering the clinical presentations, pathogenesis, and treatment of the idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. JAMA. 2011;305(2):183-190.

Wedderburn LR, McHugh NJ, Chinoy H, et al. HLA class II haplotype and autoantibody associations in children with juvenile dermatomyositis and juvenile dermatomyositis-scleroderma overlap. Rheumatology. 2007;46:1786-1791.