Chapter 6 Island Pedicle Flaps

A majority of skin cancers are located on the face. Although there are many treatment options for non-melanoma skin cancers, the surgical treatment of cutaneous neoplasia remains the gold standard of care. Skin cancer continues to show increasing prevalence in the United States.1–3 It is important, therefore, that the dermatologic surgeon understand the various reconstructive options available for surgical defects. The majority of such wounds encountered by dermatologists are created during the extirpation of skin cancers, and these skin and soft tissue wounds of the face may present significant challenges to the physician. The reconstructive choices for any particular defect may vary considerably in technical difficulty, operative morbidity, and final result. The reconstructive option that preserves or restores anatomic function and provides pleasing final cosmesis will always prove superior.

Once the surgeon has successfully removed the skin cancer, efforts may then be directed to reconstruction. The potential for functional compromise must be carefully considered. If function has been preserved during tumor removal, it must be maintained during the surgical reconstruction. If function has been lost, it must be restored. The surgical defect is critically analyzed. The missing tissue is identified and characterized. The cosmetic units involved with the wound are defined. As previously described elsewhere, the face is subdivided into cosmetic subunits.4–8 Repairs, at times, may yield improved results when subunits are defined and repaired individually instead of relying upon a single flap or graft to repair a surgical defect that traverses more than one cosmetic subunit. The aesthetic limitations of second intention healing often restrict its use on the face. Although second intention healing has been shown to provide excellent postoperative results in certain areas of the face,9 the majority of surgical wounds on the face are better suited for surgical reconstruction. Whereas those areas with concave topography (the alar groove, inner canthus and concha, for example) typically yield good results with second intention healing, wounds in other areas such as the convex malar cheek or nasal dorsum show inferior results without appropriately performed operative repairs. The predictable postoperative contraction of granulating surgical wounds may present significant risk of anatomic distortion if the wound is close to the mobile eyelid margin, ala, or lip. Moreover, this postoperative contraction seen with second intention healing may fail to effectively restore contour. Such shadowed contour deformities typically provide poor cosmetic end results. For these reasons, only a small proportion of facial surgical wounds heal better with neglect than with reconstructive procedures.

FLAP DESIGN AND CONSIDERATIONS

Many variables must be considered when examining a surgical defect and considering reconstructive options. The effective restoration of soft tissue contours improves results by reducing the visual impact of the reconstructive scars. Closure options for soft tissue defects include primary closure (side-to-side repair), split- or full-thickness skin grafts, and local or distant skin flaps. For smaller and less complex defects in areas with adequate regional tissue laxity, primary closure may often be a suitable repair choice. To achieve good cosmetic results with primary closure, the surgeon must recognize the limitations of adjacent tissue reservoirs. The mobility of nearby facial structures and their tolerance for movement must be determined prior to initiating the surgical repair. Primary closure is principally used for smaller surgical defects of relatively low complexity. When the defect is too large to rely upon local tissue laxity to close the wound in a side-by-side fashion, a skin graft or flap may be considered. Both full- and split-thickness skin grafts may be used to repair cutaneous wounds in a wide variety of locations, and the uses of skin grafts are discussed elsewhere in this text. Although skin grafts, at times, may provide excellent final cosmetic results, they suffer from several limitations. To achieve excellence in cutaneous reconstruction, the surgeon must replace the missing tissue with tissue of identical or nearly identical character. When compared to the recipient site, the donor site’s skin should have a similar amount of sun damage, sebaceous glands, terminal hair, etc. Because skin grafts are usually harvested from sites not adjacent to the surgical defect, the harvested skin’s character is often dissimilar to that of the missing skin. Moreover, to ensure the survival of a full-thickness skin graft, all of the subcutaneous fat and portions of the dermis must be removed from the graft prior to its placement. The graft, therefore, may lack sufficient volume to adequately fill the surgical wound. For these reasons, flap repairs are best suited for many wounds on the face.

The flap repair of soft tissue defects is unsurpassed in its ability to provide functional preservation, contour restoration, and overall cosmetically appropriate reconstruction. A cutaneous flap is defined as a mobile attached unit of skin and soft tissue with its associated blood supply. Flaps are used extensively to repair a wide variety of soft tissue defects following skin cancer surgery in all anatomic locations. Flaps are widely used because they can often overcome many of the pitfalls seen with alternative repair options. Cutaneous flap surgery is safe10 and reproducible. Although cutaneous flaps may yield excellent results, flaps are not without the potential for some surgical risks and operative complications. It is important that the cutaneous surgeon have a firm knowledge of relevant anatomy, flap physiology, and flap design to maximize the opportunity for success. The nuances of proper surgical technique prove to significantly influence operative outcomes. Care must be extended to flap choice, flap design, incision and flap harvesting, and suture technique.

Cutaneous flaps are typically classified based upon one of two systems: either the type of principle movement (rotation, transposition, advancement, or interpolation) or blood supply (random or axial patterned).11 Because the majority of flaps performed by dermatologists are random pattern cutaneous flaps, skin flaps are more commonly classified on the basis of movement. Random pattern flaps of varied design are supplied by the richly anastomotic dermal vasculature, and they lack the axial pattern flaps’ larger caliber, named vessels in their bases. When the flaps are properly designed and executed, the abundant vascular supply of the dermis affords random patterned flaps optimum chances for survival.

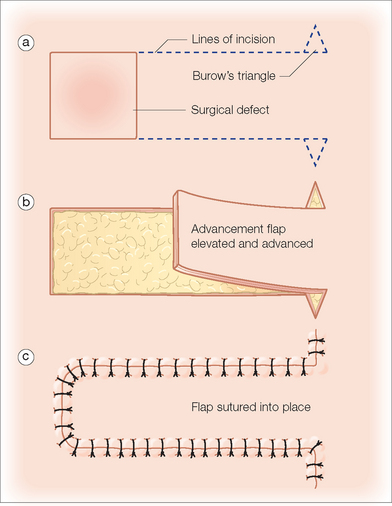

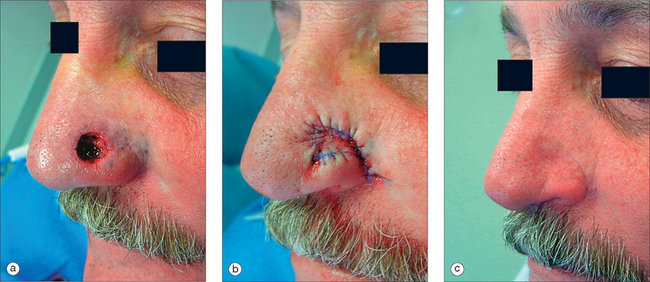

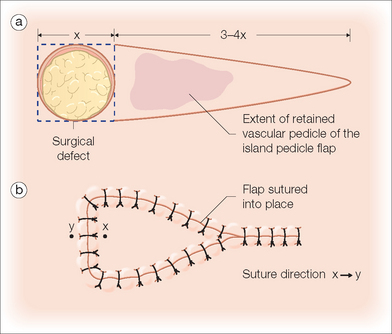

The subcutaneous island pedicle flap (also called a V–Y advancement flap) is a random pattern cutaneous flap that is a useful method of repairing small to medium-sized facial wounds.12–28 The classical advancement flap recruits contiguous tissue to repair an adjacent defect by creating a flap elevated to its base after two parallel incisions are made (Figure 6.1). The traditional advancement flap, in this regard, is limited by the mechanics of the flap’s design. With the simple advancement flap, a length:width ratio of less than 3:1 must usually be followed to ensure the perfusion of the distal portion of the elevated flap. Advancement flaps designed with length:width ratios exceeding 3:1 or flaps inseted under significantly elevated wound closure tensions may be subject to inordinately high risks of distal ischemic necrosis. The IPF has surmounted this pitfall, which has, at times, limited the usefulness and success of the advancement flap. The IPF is designed so that a nutrient vascular pedicle closer to the flap’s leading edge is retained in order to provide an increased and more predictable vascular supply. The preserved central vascular pedicle significantly improves the perfusion of the flap’s anterior margin and eliminates the relative ischemia at the leading edge of the longer traditional advancement flap. Because it has an abundantly perfused central pedicle, the IPF can tolerate longer incisions and increased closure tensions than the classical advancement flap. The careful identification and preservation of a nutrient vascular pedicle in the IPF is therefore critical for the success of the flap. The classic design of the subcutaneous island pedicle flap is best used to repair defects of the upper cutaneous lip, anterior or mid-nasal ala, and brow (Figures 6.2–6.4).12,16,19,20,22,26 The flap may also be used to effectively repair defects of the nasal dorsum, cheek, forehead, or concha (the flip-flop flap).24,25,27,28 Modifications including a buried island pedicle flap and transposition island flap may expand the utility of the flap and may be used to repair defects of the medial canthus, lateral ala, and other sites.

In the classic design of the IPF (Figure 6.5), the preserved nutrient vascular pedicle is directly underneath the central portion of the mobile flap. Variations of the IPF with the vascular pedicle relocated to a lateral margin, a de-epithelealized distal flap, and a flap with bi-level muscular pedicles have been previously described.12,15,21,24,29 However, in the author’s opinion, none of these modifications can surpass the predictably reproducible results seen with the classic design of the island pedicle flap with a central vascular pedicle.

TECHNIQUE

The proper design and execution of the island pedicle flap is obviously critical to achieving reproducible aesthetic results with minimal operative risk. Once a defect has been selected for repair with an island pedicle flap, operative consent is obtained from the patient. Routine prepping, draping, and infiltration with a local anesthetic then follow. The flap is designed as a V–Y tissue advancement. Although usually depicted as an isosceles triangle with straight edges, the flap’s long axes may be curved to place the resultant incision lines along the borders of the facial cosmetic units (for example, curvilinear incisions in the melolabial fold and along the vermilion border for an IPF used in upper lip reconstruction).

The island pedicle flap has a robust central vascular pedicle that consists of dermis, subcutaneous tissue, and underlying facial musculature. This pedicle nourishes the flap with a predictable vascular support rewarded to few other random pattern cutaneous flaps. Although categorically a random pattern cutaneous flap, the IPF has a blood supply more abundant and predictable than that of many other flap reconstructive options. This improved vascular support may be beneficial in patients with increased risks of tissue ischemia (smokers, patients with prior exposure to radiation therapy, etc). Moreover, the limited amount of required undermining and tissue mobilization associated with the proper use of the IPF may make this flap an excellent choice in patients taking anticoagulants or those with bleeding diatheses. When compared to a rotation or advancement flap used to repair similarly sized defects, the IPF typically requires less undermining, which may yield a lower risk of postoperative bleeding complications.30,31

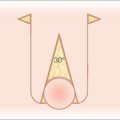

Following adequate tumor extirpation, the defect to be repaired with the island pedicle flap is thoroughly analyzed. The flap produces the best results when harvested from within the same cosmetic unit as the surgical wound. This, however, is not an absolute requisite for flap success. The flap is classically designed as an isosceles triangle adjacent to the primary defect (Figure 6.5). The length of the triangle is typically 3–4 times the width of the surgical defect. The apex of the triangle’s long sides is an angle of approximately 30°. After the flap is designed, the circular surgical defect is converted to a square and the beveled dermis is removed if the wound has resulted from a Mohs extirpation.32 It is the opinion of the author that a squared-off island flap inserted into a squared-off surgical defect has less of a chance of elevation (trapdooring) and resultant failure of contour restoration than a rounded flap placed into a rounded defect (Figure 6.6). The phenomenon of trapdooring is poorly understood. As a flap contracts in the postoperative period, circumferential movement of incipient scar tissue may force the flap to become elevated above the surrounding skin. Although, this elevation may prove aesthetically displeasing, it can usually be corrected with massage, intralesional corticosteroids, and simple observation, thereby avoiding the need for additional operative procedures. Despite previously published recommendations to oversize the flap, the best surgical results are obtained when the flap is slightly undersized.32,33 For that reason, the width of the properly designed IPF is slightly smaller than the width of the primary surgical defect. Although this minimal undersizing requires some degree of secondary tissue movement from around the borders of the primary surgical defect, this undersizing reduces the risk of postoperative flap protuberance. Oversizing or equivalent sizing the island flap to the defect simply stuffs too much flap into the surgical defect, and the flap, when cicatricial forces begin to contract, decompresses anteriorly, producing an unsightly, redundant flap that will detract from the typical aesthetic success seen with the IPF.

After the flap has been designed with attention to anatomic boundaries and flap geometry, the flap is sharply incised. The margins of the flap’s donor area are then undermined to facilitate flap advancement and donor site closure. It is important to recognize the degree of secondary tissue movement that will be required in all cases in order to avoid unwanted anatomic distortion. The primary defect’s peripheral margins are also undermined at an identical depth. Undermining the island pedicle flap itself presents the most risky portion of the reconstruction. If inadequate undermining is done, the flap will prove difficult to mobilize and thus may require excessive tensions for closure. These inappropriately elevated tensions increase the risk of flap ischemia and produce associated anatomic distortion. Conversely, if the flap is undermined without careful attention to the preservation of the central vascular pedicle, insufficient vascular supply may fail to nourish the nascent flap. Although facial flaps may have a greater and more predictable vascularity than similarly designed flaps in other locations, the facial island pedicle flap must still be executed with careful attention to surgical detail. A central pedicle of 40–50% of the flap’s area is typically adequate to ensure the flap’s survival. A significant restriction to the linear advancement of the flap may originate at the narrow apex (tail) of the flap. The apex of the flap may be incised and elevated to increase the forward sliding motion of the flap. This undermining and elevation of the flap’s tail greatly improve the flap’s mobility, but they should be limited to the exact extent necessary to advance the flap. Increasing the extent of undermining reduces the size of the nutrient vascular pedicle and therefore increases the risk of ischemic flap necrosis. The advancing margin of the flap is also undermined several millimeters, principally to assist with accurate wound edge reapproximation. This small amount of undermining also significantly improves flap movement, particularly when the tail of the flap has also been liberated from its underlying attachments.

After undermining of the recipient site, donor site, and the anterior and posterior margins of the flap, the flap and surrounding skin are elevated and hemostasis is achieved. After achieving adequate hemostasis, the flap is advanced in a V–Y manner to fill the surgical defect. The initial suture (the key stitch) is placed at the midpoint of the flap’s anterior margin to a corresponding point along the opposite margin of the primary surgical defect. This suture is placed with particular care to ensure that the flap is carefully aligned to minimize the risk of subsequent anatomic distortion. Suture technique is critical to achieve operative success. To compensate for the inevitable wound contraction seen in the postoperative period, the flap must be sutured into place with care. Buried vertical mattress sutures of absorbable material are placed in the mid-dermis. If placed correctly, each successively placed buried suture will lower the central portion of the slightly undersized island pedicle flap. At the completion of the buried suture placement, the center of the flap should be depressed 2–3 mm below the surrounding skin. This slight flap recession is important to provide a well-contoured flap after wound healing has been completed, as the flap will inevitably rise to a small extent as wound contraction occurs at the flap’s bed in the early postoperative period.33 The author has never observed a recessed flap that failed to eventually elevate to a proper position.

The classically designed island pedicle flap is a hearty flap that may be used to repair a wide variety of facial defects with elegance and minimal procedural morbidity. The flap repairs wounds with skin of excellent color and textural match. The advancement island pedicle flap should be viewed as an ideal reconstructive choice for soft tissue defects of the cutaneous lip, eyebrow, and medial cheek. Although previous authors have championed the flap as a viable reconstruction choice for distal nasal defects, the flap may prove problematic on the lower nose if the mobility of the nasal skin is limited or misjudged.15 In such a case, prominent nasal distortion may result after inadequate flap advancement because a reliance on secondary tissue movement to close the primary surgical defect is required. For small to medium-sized distal nasal wounds, alternative reconstructive choices (the bilobed and other flaps) may prove to be superior selections.

MODIFICATIONS

When preoperative assessment predicates that a central pedicle may limit the flap’s movement, lateral pedicles may be used to increase flap movement and maintain adequate flap perfusion. This design modification may prove to be important in certain anatomic areas (the temple, for example). Alternative modifications may also increase the usefulness of the IPF. The advancing margin of the island pedicle flap may be de-epithelealized and buried in yet another variation of the flap.24 This removal of the distal flap’s epidermis may provide a soft tissue platform upon which to reconstruct a nasal sill or medial canthus.

A significant variation of the island pedicle flap is the previously described transposition island pedicle flap.21 With this flap design, the flap is modified to recruit tissue from a donor site near to, but not contiguous with, the primary defect. This modification of the IPF’s design may prove to be an ideal solution to the reconstruction of lateral nasal ala or upper nasal dorsum wounds. In both areas, the design of the transposition island flap is similar. The wound’s template is transferred to a nearby reservoir of matching skin (usually located at a distance of 1–1.5 times the diameter of the surgical defect from the wound) (Figure 6.7). The template is then placed over the donor site, and it is confirmed that adequate tissue laxity exists to allow interpolation of the flap. The design of the flap can be conceptually compared to the design of the melolabial interpolation or paramedian forehead flap. However, the epidermis from the proximal portion of the flap (from the flap’s origin to the superior margin of the placed template) is removed with particular attention to ensure that the subcutaneous tissue with its vascular supply is preserved.34 The standing cutaneous deformity distal to the template is then removed. The island flap is then elevated with care to protect the deep, proximal vascular pedicle. The flap is then transposed and inset into the primary surgical defect. The proximal portion of the pedicle, lacking an overlying epidermis, is buried and covered with the repair. The donor site of the flap is then repaired. This one-stage repair of defects that have been traditionally repaired with two-stage flaps may prove useful in certain clinical circumstances such as a patient who is a poor candidate for staged reconstructive efforts or who lives a long distance from the treating physician. However, because the burying of this flap’s pedicle can occasionally cause a significant elevation/deformity near the flap’s pivot point near the medial cheek, this modification of the island pedicle flap is unlikely to entirely replace the more classically designed interpolation flaps that retain a vascular pedicle that is removed in a second surgical procedure performed several weeks after the initial creation of the flap. This fullness near the flap’s pivot point typically subsides with time and with the use of intralesional corticosteroids, but the shadowing and elevation of the medial cheek near the flap’s donor site may prove persistently troubling to the aesthetically demanding patient. Some authors advocate removing subcutaneous tissue and creating a tunnel to lay the pedicle in to reduce the bulking effect.

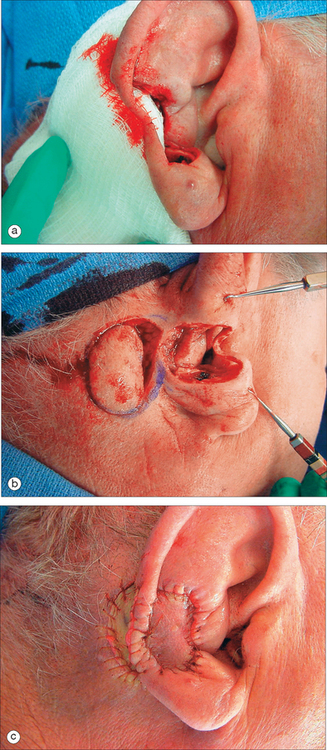

Auricular defects may also represent significant operative challenges. The three-dimensional complexity of the ear and its aesthetic prominence may obviate simpler repair options such as primary closure. Although second intention healing and skin grafting may afford good postoperative results, larger and more significant surgical wounds may require flap closures to achieve aesthetic and functional success. The island pedicle flap has been previously described to serve as a reconstructive method for conchal or scaphoid fossa defects (Figure 6.8).27,28 An appropriate donor site overlying the mastoid is selected. A template of the wound is transferred to this mastoid skin, and an island pedicle flap is incised and elevated as previously described. The flap, with its preserved vascular pedicle, is then passed through a full-thickness defect in the ear. The flap is then inserted into the wound located on the anterior aspect of the ear (the flip-flop flap). The inclusion of musculature in the flap’s base significantly improves the flap’s vascularity. The flap’s donor site may be allowed to granulate or may be repaired with a full-thickness skin graft. Like more traditional island pedicle flaps, this one-stage repair offers excellent postoperative results when used for appropriate surgical defects.

COMPLICATIONS

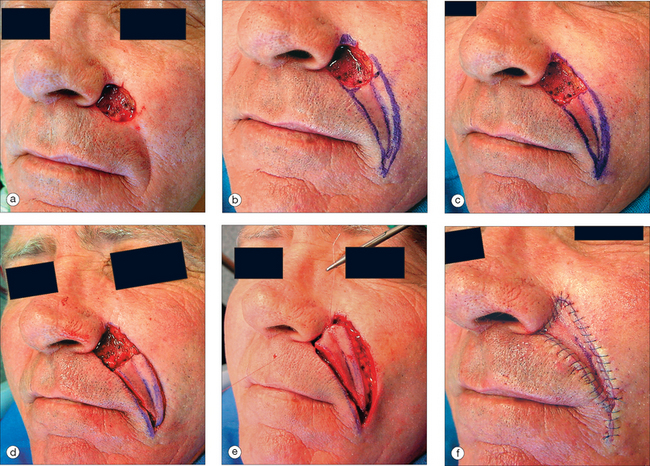

Although an excellent choice for repairing medial cheek defects, the IPF may at times prove problematic. Figure 6.9a shows a moderately sized defect of the medial cheek. Reconstructive choices include repair with one local flap, repair of the individual cosmetic units, secondary intention healing, and skin grafting. In this circumstance, reconstruction of the wound with a local flap will likely yield the best functional and aesthetic results. In this case, an inferior IPF with a central pedicle was incised and advanced to fill the defect with no distortion of the nearby mobile ala, eyelid, or lip (Figure 6.9b). The postoperative result with no additional procedures is seen in Figure 6.9c. The flap has provided effective functional reconstruction but has failed to meet the physician’s and the patient’s cosmetic expectations. The lack of exact contour restoration has limited the success of the flap. The flap’s imperfect initial design was the principal error. Because of the IPF’s inherent bulkiness, the flap must be slightly undersized to compensate for the postoperative flap elevation that inevitably accompanies wound contraction. In this case, the flap was not adequately undersized, and too much flap was “stuffed” into the surgical defect. This has resulted in persistent flap elevation. An improved result would have been obtained by undersizing the flap enough to avoid excessive tissue advanced into the primary surgical wound. Importantly, excessive undersizing of the flap must also be avoided, as too small a flap will rely on secondary tissue movement to close the primary defect. This movement will result in excessive risk of anatomic distortion. A bilateral pedicled flap with the central flap elevated may have increased the effective movement of the flap, leading to lower closure tensions and improved results. In this example, the best result would have likely been achieved with the repair of the individual cosmetic units (a flap to repair the cheek defect and a full-thickness graft to repair the nasal defect). The use of a single flap to fill a defect bridging two cosmetic units should be avoided, if possible. In this case, the oversized flap has elevated with postoperative wound contraction, and the flap has not only provided poor contour restoration but has also softened the distinction of the anatomic border separating the nose and cheek.

1 Athas WF, Hunt WC, Key CR. Changes in nonmelanoma skin cancer incidence between 1977–1978 and 1998–1999 in north central New Mexico. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12:1005-1008.

2 Joseph AK, Mark TL, Mueller C. The period prevalence and costs of treating nonmelanoma skin cancer in patients over 65 years of age covered by Medicare. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:955-959.

3 Harris RR, Griffith K, Moon TE. Trends in the incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancers in southeastern Arizona. 1995–1996. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:528-536.

4 Burget GC, Menick FJ. The subunit principle in nasal reconstruction. Plast Reconst Surg. 1985;76:239-247.

5 Burget GC. Aesthetic restoration of the nose. Clin Plast Surg. 1985;12:463-480.

6 Menick FJ. Reconstruction of the cheek. Plast Reconst Surg. 2001;108:496-503.

7 Menick FJ. Artistry in aesthetic surgery. Aesthetic perception and the subunit principle. Clin Plast Surg. 1987;14:723-735.

8 Thompson S, Menick FJ. Aesthetic facial reconstruction: blending human perception in the facial subunit theory. Plast Surg Nurs. 1994;14:211-216.

9 Zitelli JA. Wound healing by secondary intention. A cosmetic appraisal. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;9:407-415.

10 Cook JL, Perone JB. A prospective evaluation of the incidence of complications associated with Mohs micrographic surgery. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:143-152.

11 Goding GS, Hom DB. Skin flap physiology. In: Baker SR, Swanson NA, editors. Local flaps in facial reconstruction. St. Louis: Mosby; 1995:15-30.

12 Zitelli JA, Brodland DG. A regional approach to reconstruction of the upper lip. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1991;17:143-148.

13 Field L. The subcutaneously bipedicled island flap. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1980;6:454-460.

14 Ono I, Gunji H, Sato M, et al. Use of the oblique island flap in excision of small facial tumors. Plast Reconst Surg. 1993;91:1245-1251.

15 Papadopoulos DJ, Trinei FA. Superiorly based nasalis myocutaneous island pedicle flap with bilevel undermining for nasal tip and supratip reconstruction. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:530-536.

16 Narsete TA. V-Y advancement flap in upper lip reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:2464-2466.

17 Davis WH. Sideburn reconstruction with an arterial V-Y hair bearing scalp flap after excision of basal cell carcinoma. Plast Reconst Surg. 2000;106:94-97.

18 Hatoko M, Kunahara M, Shiba A, et al. Earlobe reconstruction using a subcutaneous island pedicle flap after resection of earlobe keloid. Dermatol Surg. 1998;24:257-261.

19 Kaufman AJ, Grekin RC. Repair of central upper lip (philtral) surgical defects with island pedicle flaps. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:1003-1007.

20 Gardner ES, Goldberg LH. Eyebrow reconstruction with the subcutaneous island pedicle flap. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:921-925.

21 Hairston BR, Nguyen TH. Innovations in the island pedicle flap for cutaneous facial reconstruction. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:378-385.

22 Cazualho lM, Ramos RR, Ivan DA, et al. V-Y advancement flap for the reconstruction of partial and full thickness defects of the upper lip. Scand J Plast Reconst Surg Hand Surg. 2002;36:28-33.

23 Yiomaz M, Menders A, Barutcu A. Submental artery island flap for reconstruction of the lower and mid-face. Ann Surg. 1997;39:30-35.

24 Yildirim S, Aköz T, Akan M, Avci G. Nasolabial V-Y advancement for closures of the midface defects. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:656-658.

25 Guerrerosantos J. Frontalis musculocutaneous island flap for coverage of forehead of defect. Plast Reconst Surg. 2000;105:18-22.

26 Kim KS, Huang JH, Kim DY, et al. Eyebrow island flap for reconstruction of a partial eyebrow defect. Ann Plast Surg. 2002;48:315-317.

27 Humpreys TR, Goldberg LA, Niemer DR. The postauricular (revolving door) island pedicle flap revisited. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:148-150.

28 Fader DJ, Johnson TM. Ear reconstruction utilizing the subcutaneous island pedicle (flip flop) flap. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:94-96.

29 Pontes L, Ribeiro M, Vrancks JS, Guimadaes J. The new bilaterally pedicled V-Y advancement flap for facial reconstruction. Plast Reconst Surg. 2002;109:1870-1874.

30 Field LM. Undermining subcutaneous island flaps. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:20-27.

31 Chan ST. A technique of undermining a V-Y subcutaneous island flap to maximize advancement. Br J Plast Surg. 1988;41:62-67.

32 Otley CC, Roenigk RK. Surgical Pearl: Preparing the defect for an island pedicle flap. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;2:257-258.

33 Cook JL, Yildirim S, Akoz T, Akan M, Avci G. Nasolabial V-Y advancement for closures of the midface defects. Dermatol Surg, 27. 2001:656-658. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:658-660. Commentary on:

34 Park SS. The single-stage forehead flap in nasal reconstruction. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2002;4:32-36.