Chapter 17 The Neck

The abundant skin and generous laxity of the neck make it an ideal setting for excellent surgical outcomes. The relaxed skin tension lines of the neck are easily identified, and when a surgical repair is properly aligned, the resulting scar is often almost invisible.

RELEVANT ANATOMY

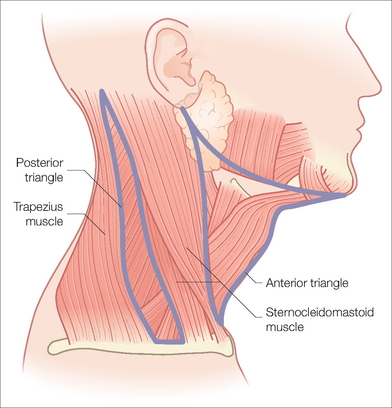

The anterior neck has been divided into anterior and posterior triangles (Figure 17.1). The boundaries of the anterior triangle of the neck are the anterior margin of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, the inferior margin of the mandible, and the midline.

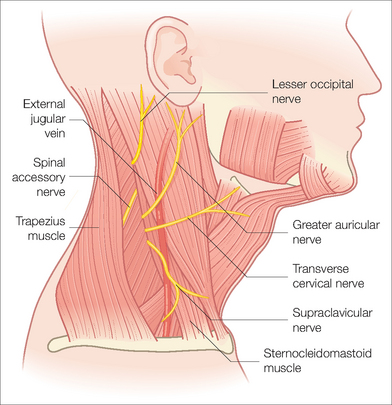

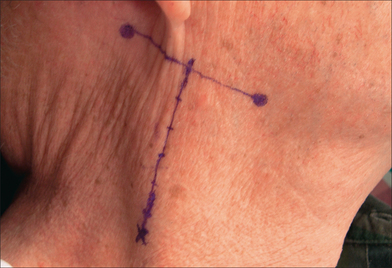

The most important anatomic structure to avoid during cutaneous surgery on the neck is the spinal accessory nerve (cranial nerve XI). This nerve emerges from under the sternocleidomastoid muscle and travels diagonally downward until it dives under the trapezius muscle (Figure 17.2). Because it innervates the trapezius muscle, damage to the spinal accessory nerve will result in winging of the scapula, difficulty in arm abduction, and shoulder pain. Erb’s point is the location where the spinal accessory nerve emerges from under the sternocleidomastoid muscle. It can be located by bisecting a horizontal line that connects the mastoid process and the angle of the mandible, and dropping a perpendicular line 6 cm inferiorly to where it intersects the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (Figure 17.3).

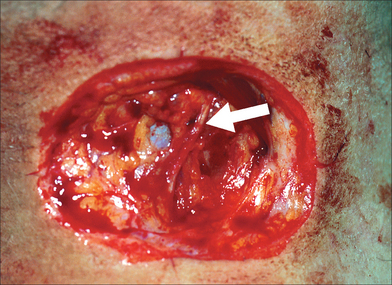

It is surprising how easily the spinal accessory nerve can be reached during surgery. Only the skin, subcutaneous fat, and superficial fascia protect it. In patients with thin skin and minimal adipose tissue, it can be remarkably superficial (Figures 17.4, 17.5).

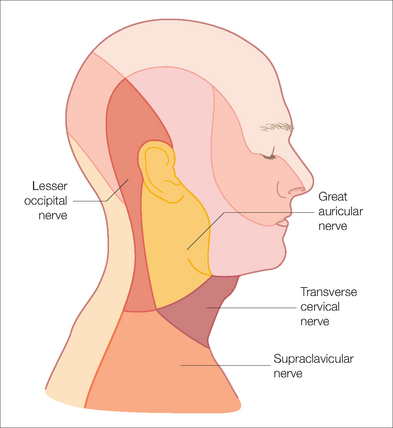

The superficial cervical plexus also emerges near Erb’s point from the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and includes the following sensory nerves: the lesser occipital nerve, the great auricular nerve, the transverse cervical nerve, and the supraclavicular nerve. These nerves provide sensation to an area that begins with the anterior and lateral neck and moves superiorly to include much of the ear and mastoid region (Figure 17.6).

RECONSTRUCTIVE OPTIONS

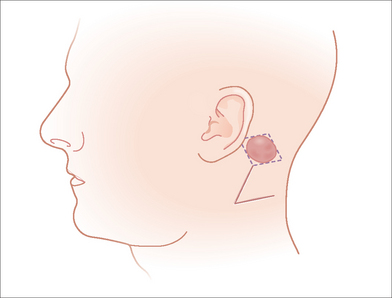

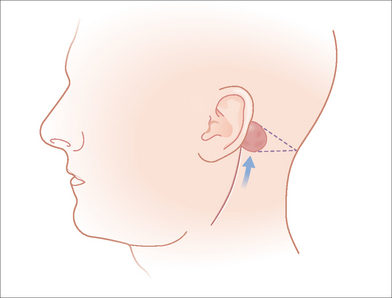

In the following example, a basal cell carcinoma was removed from the right lateral neck. The resulting defect was 11.2 × 5.7 cm2 in size (Figure 17.7), and was closed in a primary fashion (Figure 17.8). The patient is pictured six months later in Figure 17.9.

Because a primary closure is such a great option for surgical defects of the neck, it is rare that a flap or skin graft is required. Of the many flaps that may be available, transposition flaps including rhombic and bilobed flaps may be helpful for recruiting skin and laxity from distant locations. Split-thickness skin grafts and full-thickness skin grafts are also possibilities when the other options for repair are limited. However, the morbidity of a large skin graft and its donor site may outweigh the benefit to the primary defect. Wounds on the neck can also do well when they are allowed to heal by secondary intention.

Most wounds on the posterior neck can be closed primarily along skin tension lines just like on the lateral neck. However, the posterior neck is also a good location for a wound to heal by secondary intention. Even incredibly large wounds on the posterior neck can heal into remarkably thin scars. Some would argue that wounds in this area actually heal better when left to granulate than when closed primarily. The authors have treated several patients with acne keloidalis nuchae or hidradenitis suppurativa with wide excisions, and allowed them to granulate. The results are consistently excellent. Figure 17.10 shows a patient immediately after a wide excision of acne keloidalis nuchae on the posterior neck, and Figure 17.11 shows his final result after healing by secondary intention.

Neck wounds that extend onto the mastoid region can be a challenge to close because the mastoid does not share the same laxity of the neck. This is another region that does remarkably well with secondary intention healing. Pictured in Figure 17.12 is a patient with a large defect of the neck, mastoid, and posterior ear. Figure 17.13 shows the wound healing well at 4 weeks. The healing wound is shown again at 4 weeks from a different angle in Figure 17.14, and it is already possible to see that the final result will be comparable to anything that could have been achieved with a flap or graft. The contracting forces of wound closure worked to the patient’s advantage, shrinking the size of the scar as it pulled the neck skin towards the defect.

Other good options for repairing defects in the mastoid region are the rhombic transposition flap and an advancement flap. Both flaps allow the surgeon to borrow from the laxity of the neck and transfer the tissue onto the mastoid region (see Figures 17.15, 17.16).

Birkby CS, Bernstein G. Surgical anatomy. In: Wheeland RG, editor. Cutaneous surgery. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1994:46-63.

Breisch EA, Greenway HT. Cutaneous surgical anatomy of the head and neck. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1992.

Glenn MJ, Bennett RG, Kelly AP. Acne keloidalis nuchae: treatment with excision and second-intention healing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:243-246.

Gloster HM. Surgical management of extensive cases of acne keloidalis nuchae. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1376-1379.

King RJ, Motta G. Iatrogenic spinal accessory nerve palsy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1983;65:35-37.

Larrabee WF, Makielski KH. Surgical anatomy of the face. New York: Raven Press, 1993.

Mathes SJ, Nahai F. Clinical applications for muscle and musculocutaneous flaps. St Louis, MO: Mosby, 1982.

Moy RL. Atlas of cutaneous facial flaps and grafts. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger, 1990.

Salasche SJ, Bernstein G, Senkarik M. Surgical anatomy of the skin. Norwalk, CT: Appleton and Lange, 1988.

Schusterman MA. Microvascular reconstruction for head and neck cancer defects. In: Georgiade GS, Riefkohl R, Levin LS, editors. Georgiade plastic, maxillofacial and reconstructive surgery. 3rd edn. Philadelphia: Williams and Williams; 1996:529-541.

Seckel BR. Facial danger zones: avoiding nerve injury in facial plastic surgery. St Louis, MO: Quality Medical Publishing, 1994.

Williams PL, Bannister LH, Berry MM, et al. Gray’s anatomy, 38th edn. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1995.