12

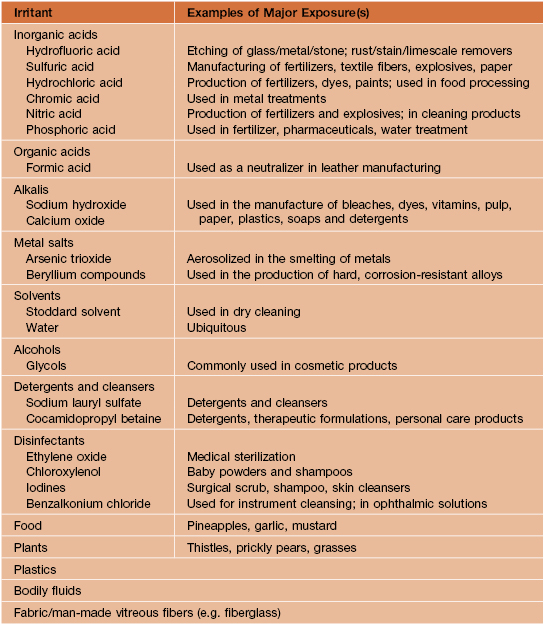

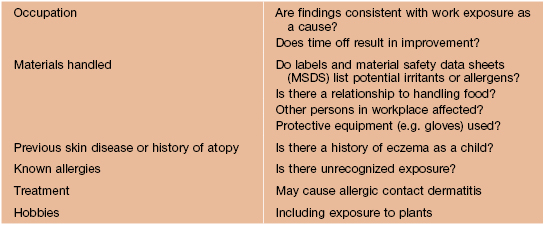

Irritant and Allergic Contact Dermatitis, Occupational Dermatoses, and Dermatoses Due to Plants

Key Points

• Irritant contact dermatitis (ICD).

– Accounts for 80% of all causes of contact dermatitis.

– Secondary to a local toxic effect caused by a topical substance or physical insult.

• Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).

– Accounts for 20% of all causes of contact dermatitis.

– Compared to ICD, more commonly presents with pruritus during the acute phase.

Irritant Contact Dermatitis

• Localized, non-immunologically mediated cutaneous inflammatory reaction (Figs. 12.1–12.4).

Fig. 12.1 Bilateral irritant contact dermatitis of the feet and ankles due to chronic occlusive footwear. Courtesy, David Cohen, MD.

Fig. 12.2 Bilateral irritant contact dermatitis of the palms secondary to repeated contact with paint solvents. Extensive patch testing excluded allergic contact dermatitis in this professional paint and crayon illustrator. Courtesy, Kalman Watsky, MD.

Fig. 12.3 Moderately severe irritant contact dermatitis of the hands due to chronic exposure to disinfecting solutions and antiseptics. The results of patch testing, latex challenge testing, and RAST testing were negative in this practicing dentist. Courtesy, David Cohen, MD.

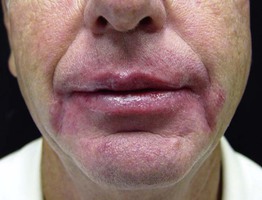

Fig. 12.4 Cheilitis due to irritant contact dermatitis. This patient had the habit of licking his lips and there is involvement of the vermilion and cutaneous lips as well as the perioral region. Courtesy, Jeffrey P. Callen.

• Secondary to a direct toxic effect.

– Chronic – erythema, lichenification, fissures, and scale.

• Commonly affects the hands (see Fig. 13.1); Table 12.1 reviews pertinent questions for when environmental exposures are suspected.

Table 12.1

Points to consider when evaluating hand dermatitis and environmental exposures are suspected.

Courtesy, Peter S. Friedmann, MD.

• A common cause of cheilitis (lip-licking; see Fig. 13.4).

• May be secondary to an occupational exposure (Table 12.2).

– Common causes are soaps and wet work, and less often petroleum products, cutting oils, and coolants.

Allergic Contact Dermatitis

• In contrast to ICD, more commonly presents with pruritus during the acute phase; the chronic phase has significant overlap with ICD (Fig. 12.5).

Fig. 12.5 Allergic contact dermatitis to shoes – acute versus chronic. A Extremely pruritic erythematous papules and papulovesicles appeared within days of wearing new sneakers; note the distribution pattern. B Pebbled and lichenified plaques with both hypo- and hyperpigmentation. The patient had a positive patch test to potassium dichromate. Courtesy, Louis A. Fragola, MD.

• Initially, well demarcated and localized to site of contact with the allergen (Figs. 12.5–12.10).

– Acute – in addition to erythema and edema, vesicobullae and weeping may develop (Fig. 12.7).

– Chronic – often lichenified with scale (Figs. 12.5B and 12.9).

Fig. 12.6 Allergic contact dermatitis. This erythematous plaque with vesiculation developed in a 14-month-old boy following the application of neomycin ointment. Courtesy, Anthony J. Mancini, MD.

Fig. 12.7 Acute allergic contact dermatitis with a prominent component of edema. Obvious edema of the shaft of the penis plus subtle crusts of the glans due to application of tiger balm (contains extracts of several plants, including mint, clove, and Chinese cinnamon). Courtesy, Louis A. Fragola, Jr., MD.

Fig. 12.8 Allergic contact dermatitis due to aloe-containing cream. The degree of involvement on the upper and lower lips is similar, as opposed to actinic cheilitis.

Fig. 12.9 Chronic allergic contact dermatitis due to glutaraldehyde. The patient was an optometrist. Courtesy, Kalman Watsky, MD.

Fig. 12.10 Clinical manifestations of Anacardiaceae dermatitis. Acute poison ivy dermatitis: A Periorbital edema, in addition to crusted and weeping plaques; B Erythematous streaks with linear vesicles; C This distribution pattern is seen in patients who wear gloves. D Patterned erythema with superimposed vesicles and bullae; E ‘Black-spot’ dermatitis: Note the black discoloration in the central portion of the edematous plaques due to plant resin. Other: F Widespread erythema and edema associated with intense pruritus after carrying logs of the poisonwood tree (Metopium toxiferum) of the family Anacardiaceae. G Weed-whacker dermatitis with widespread spotted pattern. A, Courtesy, Jean L Bolognia, MD; B, Courtesy, Joyce Rico, MD. D, Courtesy, Fitzsimons Army Medical Center Dermatology slide teaching library; G, Courtesy Louis A. Fragola, Jr., MD.

• Can have autosensitization with extension beyond original site (see Chapter 11).

• Common allergens are metals, fragrances, preservatives, and topical antibiotics, as well as plants, in particular poison ivy/oak (see below) (Fig. 12.10).

• Common causes of occupational ACD are rubber, nickel, epoxy resin, and aromatic amines.

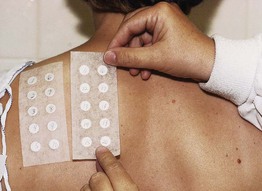

• In patch testing, specific concentrations of allergens are dissolved in petrolatum or water and placed in wells that are then applied to the patient’s back for 48 hours (Figs. 12.11 and 12.12); grading of reactions is performed at two time points (Table 12.3).

Fig. 12.11 Fixing allergens to patient’s back using Scanpor tape. The allergens will remain in place for 48 hours. Courtesy, Christen M. Mowad, MD, and James G. Marks, Jr., MD.

Fig. 12.12 Allergens being marked upon removal of Scanpor tape. Courtesy, Christen M. Mowad, MD, and James G. Marks, Jr., MD.

Table 12.3

International grading system for patch tests.

| +/– | Doubtful reaction, faint macular erythema |

| + | Weak, nonvesicular reaction with erythema, infiltration, and papules |

| ++ | Strong, vesicular reaction with infiltration and papules |

| +++ | Spreading bullous reaction |

| – | Negative reaction |

| IR | Irritant reaction |

Grading is performed at two time points after the patch tests have been in place for 48 hours (then removed; see Fig. 12.12): initially after removal and then 1–7 days later..

• Rx: short term: topical and systemic CS depending on severity; long term: avoidance of allergen(s).

Common Allergens

Metals

• Cross-reactivity not uncommon within each broad category.

• Nickel – found in costume jewelry, snaps on jeans, backs of watches, belt buckles; dimethylglyoxime test (Fig. 12.13) identifies objects that release nickel (can purchase dimethylglyoxime at http://www.drrecommended.com).

Fig. 12.13 Allergic contact dermatitis to nickel. A Excoriated pink plaques due to nickel within the belt buckle. B Facial dermatitis due to nickel within a cellular phone. The latter is demonstrated by a positive dimethylglyoxime test (pink indicator). A, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD; B, Courtesy, Christen M. Mowad, MD, and James G. Marks, Jr., MD.

• Chromate – found in metals, leather, cement.

• Cobalt – used to harden metals; cosmetics, enamel, ceramics, hair dyes, and joint replacements.

• Gold – found in jewelry, dental fillings, and some electronics.

Topical Antibiotics

Fragrances

Other Important Allergens

Topical Corticosteroids

• Can cause ACD in up to 6% of patients.

• If CS allergy is suspected/confirmed, use of a CS from a different class can be considered (see Appendix).

Additional allergens include paraphenylenediamine in temporary tattoos and hair dyes, acrylates in artificial nails, thiuram in rubber and makeup applicators, formaldehyde resin in nail polish, components of adhesives, and blue dyes in textiles.

Systemic Contact Dermatitis

• Systemic exposure to a chemical/allergen to which the patient has had prior sensitization (Table 12.4; Fig. 12.14); e.g. administration of oral diphenhydramine to a patient previously sensitized to the topical formulation.

Table 12.4

Examples of topical allergens that may result in systemic contact dermatitis after systemic exposure.

| Cutaneous Allergen | Systemic Exposure |

| Ethylenediamine hydrochloride | Aminophylline, hydroxyzine/cetirizine |

| Poison ivy | Cashews, mango peel |

| Fragrance (balsam of Peru) | Foods, sodas, mouthwashes, spices |

| Sorbic acid | Preservative in food |

| Nickel and other metal salts | Nickel (and other metal salts) in food |

| Quinolones | Oral antibiotics |

| Neomycin | Streptomycin, kanamycin |

| Thiuram | Disulfiram |

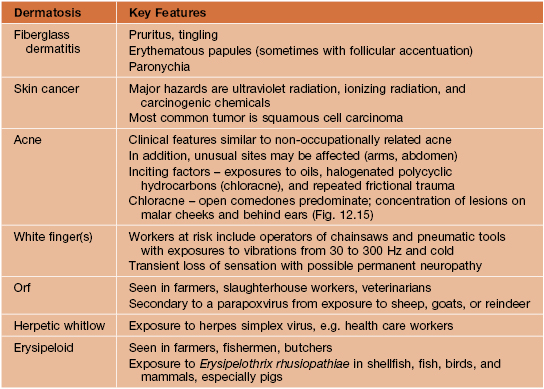

Occupational Dermatoses

• Most commonly an irritant > allergic contact dermatitis.

• Other occupational dermatoses include contact urticaria (see Chapter 14), skin cancer, folliculitis (see Chapter 31), contact leukoderma (see Chapter 54), foreign body reactions, and infections (Table 12.5).

Plant Dermatoses

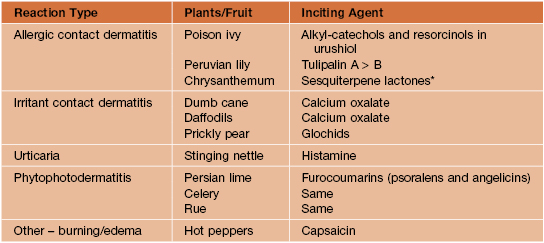

• Plants can cause a variety of skin reactions, including ACD (Fig. 12.10), ICD, urticaria, and phytophotodermatitis (Table 12.6).

Table 12.6

Most common skin reactions to plants.

Some plants can cause more than one reaction; e.g. garlic can cause ACD (diallyldisulfide), ICD, and urticaria.

* Can cause airborne contact dermatitis and positive in chronic actinic dermatitis.

• ACD to plants that contain urushiol.

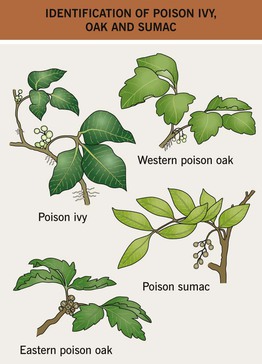

– Commonly secondary to poison ivy, genus Toxicodendron (Fig. 12.16) – compound leaves with three leaflets and flowers/fruits arising from the axillary position; black dots of urushiol often present on leaves.

Fig. 12.16 Characteristic features useful for identifying poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac. With permission from the American Journal of Contact Dermatitis.

– Allergen-containing smoke can cause respiratory tract inflammation, systemic contact dermatitis, and temporary blindness.

– After contact with urushiol, a sensitized person develops erythema, vesicles/bullae, and edema within 2 days; the reaction can last 2 or 3 weeks (Fig. 12.10).

– Erythema, vesicles/bullae, and subsequent hyperpigmentation; often in linear streaks or bizarre configurations; however, hyperpigmentation may be the only clinical finding (Figs. 12.17 and 12.18).

Fig. 12.17 Bullous phase of phytophotodermatitis. There was associated burning but no pruritus, and the linear bullae were replaced by hyperpigmentation. Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

Fig. 12.18 Phytophotodermatitis. Streaky hyperpigmentation due to contact with lime followed by exposure to sunlight. Courtesy, Anthony J. Mancini, MD.

– Commonly secondary to furocoumarins (psoralens and angelicins) in plants, e.g. limes, celery, false Bishop’s weed, and rue (Fig. 12.18).

For further information see Chs. 14, 15, 16 and 17. From Dermatology, Third Edition.