Chapter 34 Iron Treatment

Efficacy of Iron Treatment for Restless Legs Syndrome

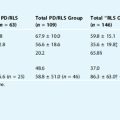

Although there are substantial data implicating a primary role for iron insufficiency in restless legs syndrome (RLS) (see Chapter 10), the actual effectiveness of iron treatment in RLS has been underexplored and relatively limited in its scientific assessment. The routes of administration available for iron therapy are oral, intravenous, and intramuscular. Oral and intravenous treatments have been studied in RLS. Oral iron treatment has all the limitations associated with a gut-blood-barrier physiology (see Chapter 9). There is high absorption (20% to 30%) of iron under severe iron deficient conditions (ferritin <5 μg/L), but absorption drops exponentially with increasing body iron stores: absorption of about 2% with ferritin of 60 to 80 μg/L and absorption of about 1% with ferritin above 100 μg/L. Those studies that have reported a benefit of oral iron treatment in RLS have been open-label design, and patients with low or deficient iron stores had been treated.1,2 There is one randomized, double-blind study of oral iron therapy in RLS.3 In this study, patients received either 130 mg of iron per day or placebo over a 12- to 14-week period. The average baseline serum ferritin levels were about 150 μg/L. Iron treatment showed no benefits and, not surprisingly, the average ferritin did not change. Therefore, the study did not prove that iron was ineffective as a treatment for RLS, only that the route of administration was ineffective in raising the body iron stores.

The limitation imposed by the gut’s restriction on iron absorption can be bypassed by giving iron intravenously. Nordlander4 was the first to demonstrate that multiple, small intravenous doses of iron could bring about marked improvements in RLS symptoms. The range of the total cumulative doses of iron given was approximately 300 to 1000 mg. Twenty-one of 22 patients reported substantial improvements of symptoms. These patients were not anemic before treatment. In another open-label study, 10 nonanemic subjects with idiopathic RLS each received a single, 1000-mg infusion of iron dextran. Seven of 10 subjects reported improvements with 6 of 10 reporting a complete resolution of symptoms.5 Not only did symptoms improve, but also the periodic limb movement rates dropped significantly from baseline values following treatment.

Despite the initial improvements in symptoms, the majority of patients in both studies had, on average, a return of symptoms within 5 to 6 months. Nordlander4 reports giving supplemental intravenous iron treatments to some of those whose symptoms returned, but the outcome of supplemental treatment was not reported. In the study by Earley and colleagues,5 the six subjects who had a complete resolution of the symptoms with the initial 1000-mg treatment were enrolled in a supplemental study to receive a further 450 mg of intravenous iron if their symptoms returned. Of the six individuals, one had no recurrence of symptoms beyond 3 years, whereas the remaining five had symptoms return within 3 to 12 months. Over a 2-year treatment course, as few as one to as many as four separate 450-mg intravenous doses were needed to maintain these patients free of symptoms. Serum ferritin levels were checked at baseline and monthly for the duration of the study. The most significant finding was that the serum ferritin levels dropped faster than predicted. Using the ferritin values as an estimate of body iron stores, the drop in ferritin seen after the infusions suggested that patients were losing iron at rates 2 to 11 times greater than normal. The reason for this rapid iron loss was not clear, but obvious causes such as blood loss or blood donation were not identified. The unexplained iron loss could certainly explain why the large doses of iron did not maintain patients symptom free for longer periods of time.

Another study of intravenous iron treatment of RLS involved a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of intravenous iron dextran given to RLS patients with end-stage renal disease who were on dialysis.6 Eleven subjects received a single 1000-mg intravenous dose of iron dextran and 14 subjects received placebo. The iron treatment group improved significantly with reduced RLS symptoms at weeks 1 and 2 postinfusion, but by week 4, the initial improvements were no longer apparent. Iron metabolism in patients with end-stage renal disease on dialysis is more complicated than that under “normal” renal condition. The relatively short-lived benefits may reflect the rapid iron loss seen under these clinical conditions, and may indicate the need for repeated iron infusions, as found in the other studies mentioned earlier.

Options for Oral and Intravenous Iron Treatments for Restless Legs Syndrome

There are different oral preparations of iron (ferrous sulfate 325 mg [alternately labeled as “65 mg of elemental iron”], ferrous fumarate 200 mg (66 mg of elemental iron), or ferrous gluconate 325 mg [sometimes better tolerated, but it has only 38 mg of elemental iron per pill]). A specific patient may better tolerate one preparation than the others. With iron deficiency anemia, a starting point is 50 to 65 mg of elemental iron, three times a day. Reduced stomach acidity (e.g., by use of medications, calcium, or food) reduces iron absorption. Therefore, oral iron should be ingested on an empty stomach (no food, milk, or any other calcium-containing vitamins) along with a minimum of 100 mg of vitamin C. Serum ferritin and percent transferrin saturation (%sat) should be checked 3 months after initiating treatment and then every 3 to 6 months thereafter, depending on how rapidly the initial serum ferritin level changed. Iron treatment should be stopped if elevated values of %sat or ferritin occur, because some patients with RLS may also have unrecognized hemochromotosis.7

There are three preparations of intravenous iron that are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of iron deficiency anemia. Silverman and Rodgers8 published a comparison of the three parental forms of intravenous iron and a guide to their administration. Iron dextran (INFeD, Imferon, DexFerrum) has been associated with acute anaphylaxis, which appears to be related to the dextran component. Sodium ferric gluconate (Ferrlecit) and iron sucrose (Venofer) do not contain polymerized dextran and have not, to date, been associated with anaphylaxis. When given at the approved dosing schedules, the side effects are relatively uncommon and include drop in blood pressure, headaches, nausea, vomiting, and other gastrointestinal symptoms.

1. O’Keeffe ST, Gavin K, Lavan JN. Iron status and restless legs syndrome in the elderly. Age Ageing. 1994;23:200-203.

2. Ekbom KA. Restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 1960;10:868-873.

3. Davis BJ, Rajput A, Rajput ML, et al. A randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial of iron in restless legs syndrome. Eur Neurol. 2000;43:70-75.

4. Nordlander NB. Therapy in restless legs. Acta Med Scand. 1953;145:453-457.

5. Earley CJ, Heckler D, Horská A, et al. The treatment of restless legs syndrome with intravenous iron dextran. Sleep Med. 2004;5:231-235.

6. Sloand JA, Shelly MA, Feigin A, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of intravenous iron dextran therapy in patients with ESRD and restless legs syndrome. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:663-670.

7. Barton JC, Wooten VD, Acton RT. Hemochromatosis and iron therapy of restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2001;2:249-251.

8. Silverstein SB, Rodgers GM. Parenteral iron therapy options. Am J Hematol. 2004;76:74-78.