7

Iris and Pupils

Relative Afferent Pupillary Defect

Mesodermal Dysgenesis Syndromes

Trauma

Definition

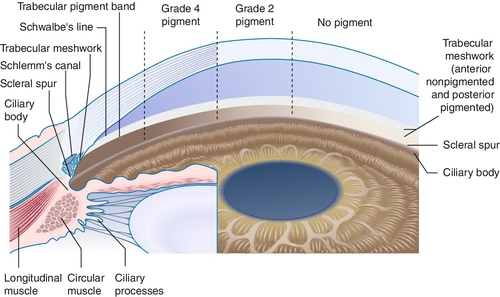

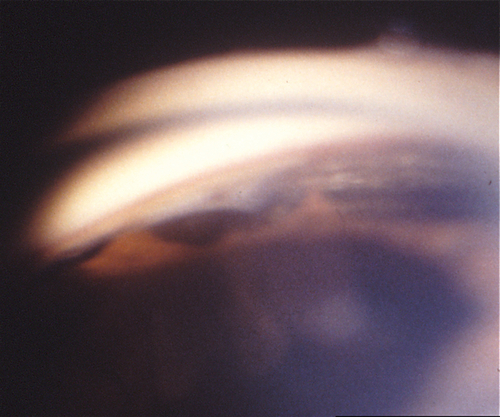

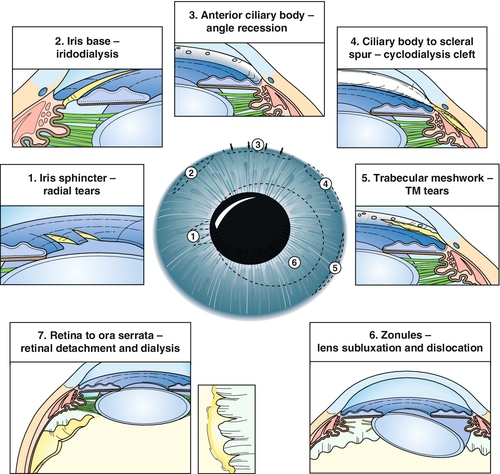

Angle Recession

Tear in ciliary body between longitudinal and circular muscle fibers. Appears as broad blue-gray band (ciliary body) on gonioscopy; associated with hyphema at time of injury. If more than two-thirds of the angle is involved, 10% develop glaucoma from scarring of angle structures.

Cyclodialysis

Disinsertion of ciliary body from scleral spur. Appears as broad white band (sclera) on gonioscopy; associated with hyphema at time of injury; may develop hypotony.

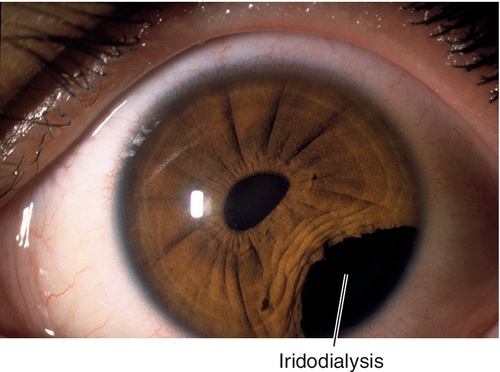

Iridodialysis

Disinsertion of iris root from ciliary body. Appears as peripheral iris hole; associated with hyphema at time of injury.

Sphincter Tears

Small radial iris tears at pupillary margin. May be associated with hyphema at time of injury; may result in permanent pupil dilation (traumatic mydriasis) and anisocoria.

Symptoms

Pain, photophobia, red eye; may have decreased vision, monocular diplopia or polyopia.

Signs

Normal or decreased visual acuity, conjunctival injection, subconjunctival hemorrhage, anterior chamber cells and flare, hyphema, unusually deep anterior chamber, iris tears, abnormal pupil, angle tears, iridodonesis, increased or decreased intraocular pressure; may have other signs of ocular trauma including lid or orbital trauma, dislocated lens, phacodonesis, cataract, vitreous hemorrhage, commotio retinae, retinal tear or detachment, choroidal rupture, or traumatic optic neuropathy; may have signs of glaucoma with increased intraocular pressure, optic nerve cupping, nerve fiber layer defects, and visual field defects.

Differential Diagnosis

See above, distinguish by careful gonioscopy; also, surgical iridectomy or iridotomy, iris coloboma, essential iris atrophy, Reiger’s anomaly.

Evaluation

• Check the angle with gonioscopy and rule out retinal tears or detachment with scleral depression if the globe is intact and there is no hyphema.

• B-scan ultrasonography if unable to visualize the fundus. Consider ultrasound biomicroscopy to evaluate angle structures and localize the injury.

• Rule out open globe and intraocular foreign body (see Chapter 4).

Prognosis

Depends on amount of damage; poor when associated with angle recession glaucoma or chronic hypotony.

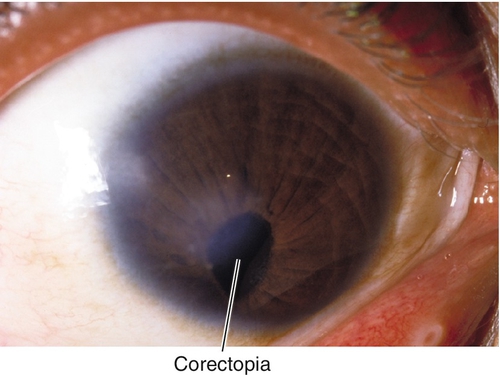

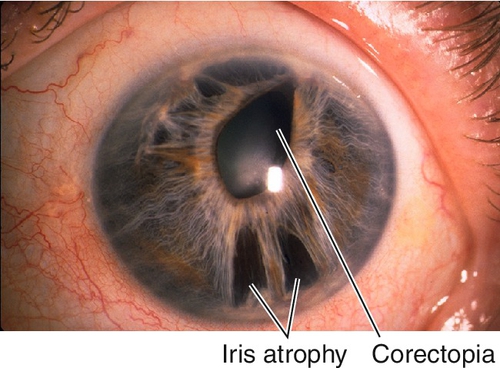

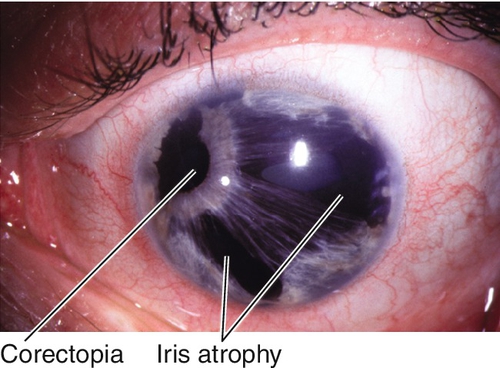

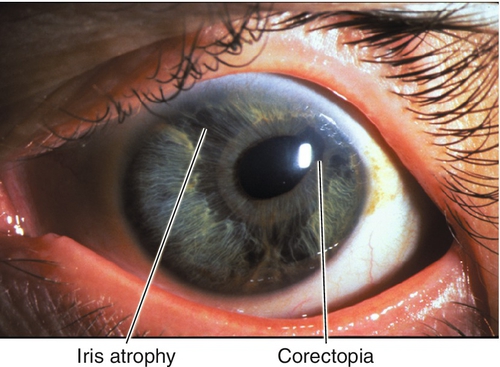

Corectopia

Definition

Displaced, ectopic, or irregular pupil.

Etiology

Mesodermal dysgenesis syndromes, iridocorneal endothelial (ICE) syndromes, chronic uveitis, trauma, postoperative, ectopia lentis et pupillae (corectopia associated with lens subluxation).

Symptoms

Asymptomatic; may have glare or decreased vision.

Signs

Normal or decreased visual acuity; distorted, malpositioned pupil.

Evaluation

• Rule out open globe (peaked pupil after trauma, see Chapter 4).

Prognosis

Depends on etiology and degree of malposition (distance from visual axis). Usually benign if mild, isolated, and nonprogressive (i.e., postoperative). However, if associated with other findings or progressive, visual loss can occur.

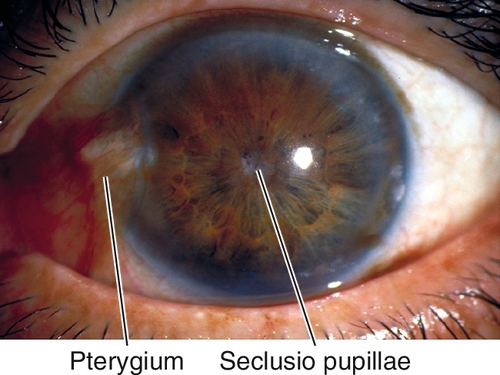

Seclusio Pupillae

Definition

Posterior synechiae (iris adhesions to the lens) at the pupillary border for 360°.

Etiology

Inflammation (anterior uveitis, see Chapter 6).

Symptoms

Asymptomatic; may have pain, red eye, and decreased vision.

Signs

Normal or decreased visual acuity, posterior synechiae, poor or irregular pupil dilation, increased intraocular pressure, acute or chronic signs of iritis, including anterior chamber cells and flare, keratic precipitates, iris atrophy, iris nodules, cataract, and cystoid macular edema.

Differential Diagnosis

Occlusio pupillae (fibrotic membrane across the pupil), persistent pupillary membrane.

Evaluation

• Consider anterior uveitis workup (see Chapter 6).

Prognosis

Depends on etiology; poor if glaucoma has developed.

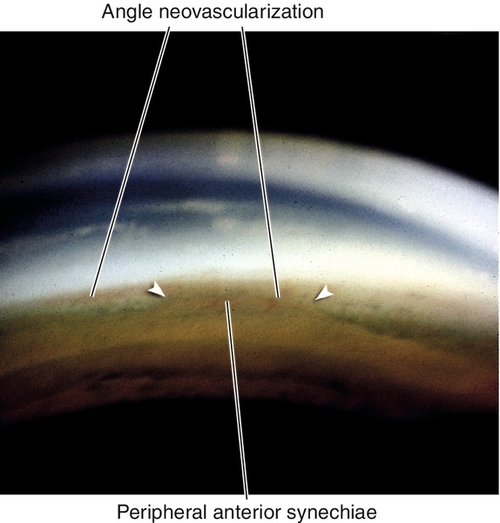

Peripheral Anterior Synechiae

Definition

Peripheral iris adhesions to the cornea or angle structures; extensive peripheral anterior synechiae can cause increased intraocular pressure and angle-closure glaucoma.

Etiology

Peripheral iridocorneal apposition due to previous pupillary block, flat or shallow anterior chamber, or inflammation.

Symptoms

Asymptomatic; may have symptoms of angle-closure glaucoma (see Chapter 6).

Signs

Iris adhesions to Schwalbe’s line and cornea; may have signs of angle-closure glaucoma with increased intraocular pressure, optic nerve cupping, nerve fiber layer defects, and visual field defects.

Differential Diagnosis

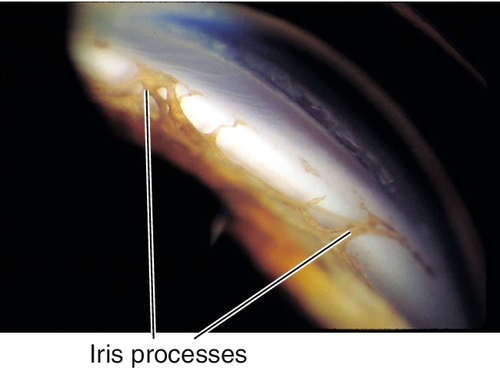

Iris processes (mesodermal dysgenesis syndromes [see below]).

Evaluation

• Check visual fields in patients with elevated intraocular pressure or optic nerve cupping to rule out glaucoma.

Prognosis

Usually good; depends on extent of synechial angle closure and intraocular pressure control.

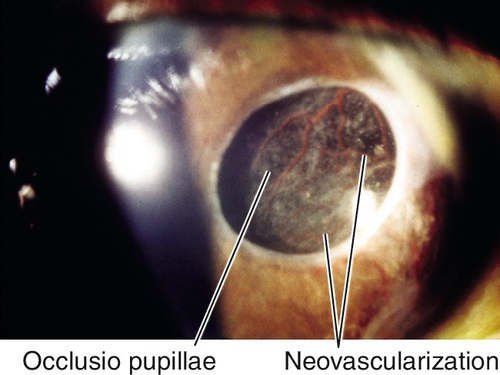

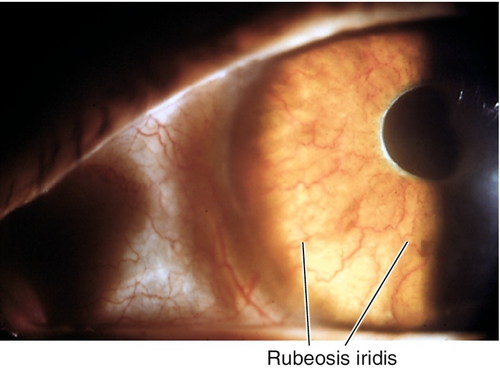

Rubeosis Iridis

Definition

Neovascularization of the iris and angle.

Etiology

Ocular ischemia; most commonly occurs with proliferative diabetic retinopathy, central retinal vein occlusion, and carotid occlusive disease; also associated with anterior segment ischemia, chronic retinal detachment, tumors, sickle cell retinopathy, chronic inflammation, and other rarer causes.

Symptoms

Can be asymptomatic if no angle involvement; angle involvement may lead to neovascular glaucoma (see below) with decreased vision or other symptoms of angle-closure glaucoma (see Chapter 6).

Signs

Normal or decreased visual acuity, abnormal blood vessels on iris and angle, particularly at pupillary margin and around iridectomies; may have spontaneous hyphema, or retinal lesions; may have signs of angle-closure glaucoma with increased intraocular pressure, optic nerve cupping, nerve fiber layer defects, and visual field defects.

Differential Diagnosis

See above.

Evaluation

• Check visual fields in patients with elevated intraocular pressure or optic nerve cupping to rule out glaucoma.

• Consider fluorescein angiogram to narrow differential diagnosis and determine cause of ocular ischemia if not apparent on direct examination.

• Consider medical consultation for systemic diseases including duplex and Doppler scans of carotid arteries to rule out carotid occlusive disease.

Prognosis

Poor; the rubeotic vessels may regress with appropriate therapy, but most causes of neovascularization are chronic progressive diseases.

Neovascular Glaucoma

Definition

A form of secondary angle-closure glaucoma in which neovascularization of the iris and angle causes occlusion of the trabecular meshwork.

Etiology

Any cause of rubeosis iridis (see above).

Symptoms

Decreased vision and symptoms of angle-closure glaucoma (see Chapter 6).

Signs

Decreased visual acuity; abnormal blood vessels on iris and angle, particularly at pupillary margin and around iridectomies; increased intraocular pressure, optic nerve cupping, nerve fiber layer defects, and visual field defects; may have corneal edema, spontaneous hyphema, or retinal lesions.

Differential Diagnosis

As for rubeosis iridis (see above), and other forms of secondary angle-closure glaucoma (see Chapter 6).

Evaluation

• Check visual fields.

• Consider fluorescein angiogram to narrow differential diagnosis and determine cause of ocular ischemia if not apparent on direct examination.

• Consider medical consultation for systemic diseases, including duplex and Doppler scans of carotid arteries to rule out carotid occlusive disease.

Prognosis

Poor; the rubeotic vessels may regress with appropriate therapy, but most causes of neovascularization are chronic progressive diseases.

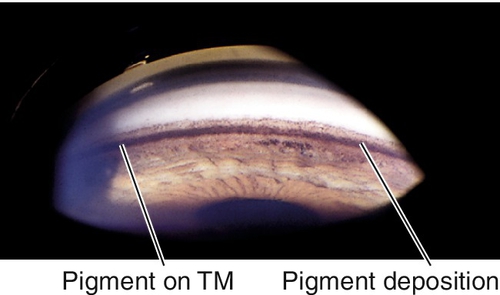

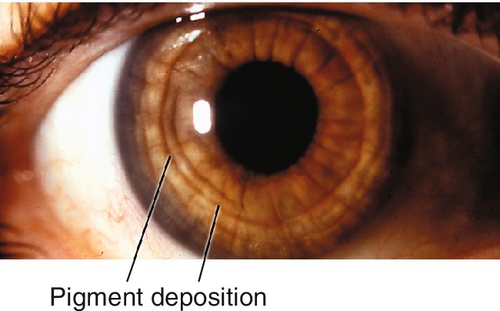

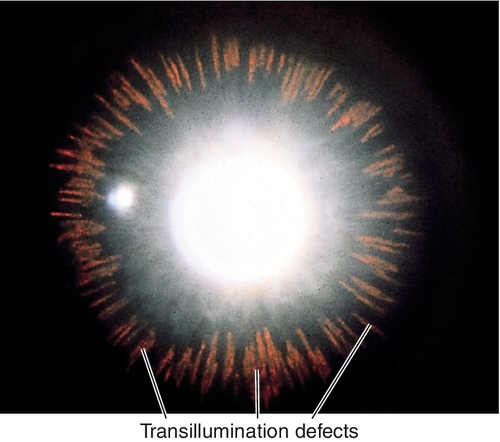

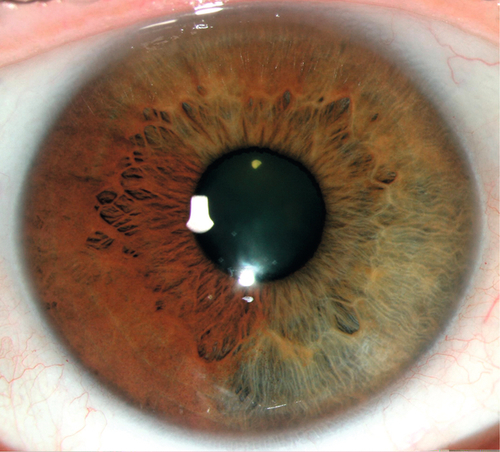

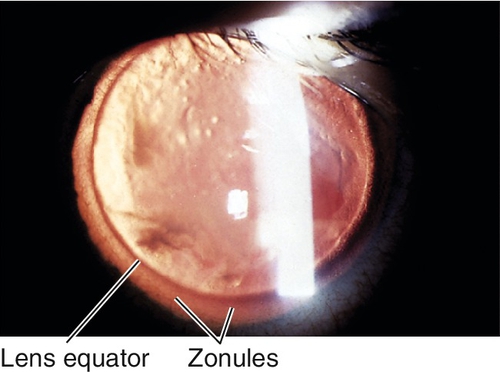

Pigment Dispersion Syndrome

Definition

Liberation of pigment from the iris with subsequent accumulation on anterior segment structures.

Etiology

Chafing of posterior iris surface on zonules produces pigment dispersion.

Epidemiology

More common in 20- to 50-year-old Caucasian men and in patients with myopia; affected women are usually older; associated with lattice degeneration in 20% of cases and retinal detachment in up to 5% of cases; 25–50% develop pigmentary glaucoma. Mapped to chromosome 7q35-q36 (GPDS1 gene).

Symptoms

Asymptomatic; exercise or pupil dilation can cause pigment release with acute elevation of intraocular pressure and symptoms including halos around lights and blurred vision.

Signs

Radial, midperipheral, iris transillumination defects, pigment on corneal endothelium (Krukenberg spindle), posterior bowing of midperipheral iris, dark pigment band overlying trabecular meshwork, pigment in iris furrows and on anterior lens capsule; may have signs of glaucoma with increased intraocular pressure, optic nerve cupping, nerve fiber layer defects, and visual field defects (see below); may have pigmented anterior chamber cells, especially following pupil dilation.

Differential Diagnosis

Uveitis, albinism, pseudoexfoliation syndrome, iris atrophy.

Evaluation

• Check visual fields in patients with elevated intraocular pressure or optic nerve cupping to rule out glaucoma.

Prognosis

Usually good; poorer if pigmentary glaucoma develops.

Pigmentary Glaucoma

Definition

A form of secondary open-angle glaucoma caused by pigment liberated from the posterior iris surface (i.e., a sequela of uncontrolled increased intraocular pressure in pigment dispersion syndrome).

Epidemiology

Develops in 25% to 50% of patients with pigment dispersion syndrome; same associations as in pigment dispersion syndrome (see above). Mapped to chromosome 7q35-q36.

Mechanism

Obstruction of the trabecular meshwork by dispersed pigment and pigment-laden macrophages.

Symptoms

Asymptomatic; may have decreased vision or constricted visual fields in late stages; exercise or pupil dilation can cause pigment release with acute elevation of intraocular pressure and symptoms including halos around lights and blurred vision.

Signs

Normal or decreased visual acuity, large fluctuations in intraocular pressure (especially with exercise); similar ocular signs as in pigment dispersion syndrome (see above), optic nerve cupping, nerve fiber layer defects, and visual field defects.

Differential Diagnosis

Primary open-angle glaucoma, other forms of secondary open-angle glaucoma.

Evaluation

• Check visual fields.

• Stereo optic nerve photos are useful for comparison at subsequent evaluations.

Prognosis

Poorer than primary open-angle glaucoma.

Iris Heterochromia

Definition

Heterochromia Iridis

Unilateral; single iris with two colors (iris bicolor).

Heterochromia Iridum

Bilateral; irises are different colors (e.g., one blue, one brown).

Etiology

Congenital

Hypochromic (involved eye lighter)

Congenital Horner’s syndrome, Waardenburg’s syndrome, Hirschsprung’s disease, Perry–Romberg hemifacial atrophy.

Hyperchromic (involved eye darker)

Ocular or oculodermal melanocytosis, iris pigment epithelium hamartoma.

Acquired

Hypochromic

Acquired Horner’s syndrome, juvenile xanthogranuloma, metastatic carcinoma, Fuchs’ heterochromic iridocyclitis, stromal atrophy (glaucoma or inflammation).

Hyperchromic

Siderosis, hemosiderosis, chalcosis, medication (topical prostaglandin analogues for glaucoma), iris nevus or melanoma, iridocorneal endothelial syndrome, iris neovascularization.

Symptoms

Usually asymptomatic; depends on etiology.

Signs

Iris heterochromia; blepharoptosis, miosis, and anhidrosis in Horner’s syndrome; white forelock, premature graying, leucism (cutaneous hypopigmentation), facial anomalies, dystopia canthorum, and deafness in Waardenburg’s syndrome; skin, scleral, and choroidal pigmentation in ocular or oculodermal melanocytosis; anterior chamber cells and flare, keratic precipitates, and increased intraocular pressure in uveitis, siderosis, and chalcosis; may have intraocular foreign body (siderosis, chalcosis), old hemorrhage (hemosiderosis), or tumor.

Differential Diagnosis

See above.

Evaluation

• Consider B-scan ultrasonography if unable to visualize the fundus.

• Consider orbital computed tomography (CT) scan or radiographs to rule out intraocular foreign bodies.

• Consider electroretinogram (ERG) to evaluate retinal function in siderosis, hemosiderosis, and chalcosis.

• Consider medical consultation.

Prognosis

Depends on etiology.

Anisocoria

Definition

Inequality in the size of the pupils.

Etiology

Greater Anisocoria in Dark (Abnormal Pupil is Smaller)

Horner’s syndrome, Argyll Robertson pupil, iritis, pharmacologic (miotic agent, narcotic, insecticide).

Greater Anisocoria in Light (Abnormal Pupil is Larger)

Adie’s tonic pupil, cranial nerve (CN) III palsy, Hutchinson’s pupil (uncal herniation with CN III entrapment in a comatose patient), pharmacologic (mydriatic, cycloplegic, cocaine, hallucinogen), iris damage (traumatic, ischemic, surgical, or Urrets–Zavalia syndrome).

Anisocoria Equal in Light and Dark

Physiologic (difference in pupil size ≤ 1 mm, and proportion of pupil areas is constant in all lighting).

Epidemiology

Up to 20% of population has physiologic anisocoria; may fluctuate, be intermittent, and even reverse.

Symptoms

Asymptomatic; may have glare, pain, photophobia, diplopia, or blurred vision, depending on etiology.

Signs

Involved pupil may be larger or smaller, round or irregular, reactive or nonreactive; may constrict to accommodation but not to light (light-near dissociation; found in Adie’s tonic pupil and Argyll Robertson pupil); may have ptosis and limitation of extraocular movements (CN III palsy); may have other signs depending on etiology.

Evaluation

• Gonioscopy and tonometry in traumatic cases to assess associated angle structure damage.

• Greater anisocoria in dark (abnormal pupil is smaller): Pharmacologic pupil testing (Note: testing must be performed before cornea has been manipulated; i.e., before any drops, applanation, or other tests have been performed; otherwise the test may be invalid):

(2) Topical hydroxyamphetamine 1% (Paredrine): Equal dilation = central or preganglionic Horner’s syndrome; asymmetric dilation = postganglionic Horner’s syndrome.

Note: tests cannot be performed on the same day or will be invalid.

• Greater anisocoria in light (abnormal pupil is larger): Pharmacologic pupil testing:

(2) Topical pilocarpine 1%: Constricts = CN III palsy; no constriction = pharmacologic dilation.

• Lab tests: Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test and fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) test for syphilis (Argyll Robertson pupil).

• Lumbar puncture for VDRL, FTA-ABS, total protein, and cell counts to rule out neurosyphilis (Argyll Robertson pupil).

• Consider head, neck, or chest CT scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to rule out masses and vascular anomalies (Horner’s syndrome, CN III palsy).

• May require medical consultation.

Prognosis

Often benign; depends on etiology.

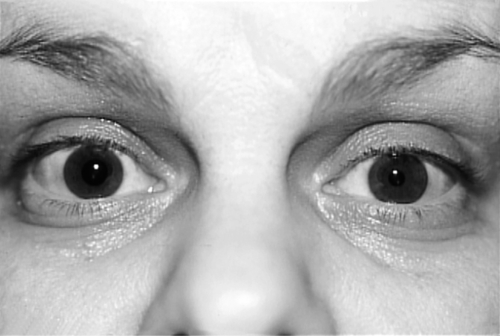

Adie’s Tonic Pupil

Definition

Idiopathic, benign form of internal ophthalmoplegia.

Etiology

Denervation hypersensitivity due to a lesion in the ciliary ganglion or short posterior ciliary nerves with receptor upregulation.

Epidemiology

Usually occurs in 20–40-year-old women (90%); 80% unilateral (may become bilateral over time).

Symptoms

Asymptomatic; may have blurred near vision and photophobia.

Signs

In the acute stage, anisocoria is greater in light than dark, dilated pupil with poor light response, segmental palsy with vermiform (worm-like) movements, slow or tonic near response (constriction and redilation), poor accommodation, light-near dissociation; 70% have decreased deep tendon reflexes (Adie’s syndrome). In the chronic stage, the pupil often becomes small and poorly reactive. Similar pupillary findings may be associated with systemic autonomic dysfunction (Riley–Day syndrome).

Differential Diagnosis

Iris ischemia or trauma, pupil-involving partial CN III palsy (almost always has oculomotor signs), botulism, and any cause of light-near dissociation (unilateral total afferent visual loss, Argyll Robertson pupil, dorsal midbrain syndrome, aberrant regeneration of CN III, diabetes mellitus, amyloidosis, sarcoidosis).

Evaluation

• Pharmacologic pupil testing: Topical pilocarpine 0.1% or methacholine 2.5% (see Anisocoria section). Adie’s tonic pupil constricts (normal does not) due to cholinergic supersensitivity; false-positive test result may occur in CN III palsy. (If recent onset, no response to dilute pilocarpine may be seen.)

Prognosis

Good; accommodative paresis is usually temporary (months).

Argyll Robertson Pupil

Definition

Small, irregular pupil that reacts briskly to near (accommodation), but not to light; usually bilateral and asymmetric.

Etiology

Associated with tertiary syphilis; thought to be due to damage to central pupillary pathways from the retina to the Edinger–Westphal nucleus in the midbrain.

Symptoms

Asymptomatic.

Signs

Miotic, irregular pupils, light-near dissociation (no reaction to light but normal near response [accommodation]), poor dilation; may have anisocoria (usually greater in dark than light), may have stigmata of congenital syphilis (e.g., Hutchinson’s triad, fundus changes, skeletal deformities).

Differential Diagnosis

Argyll Robertson-like pupils occur in diabetes mellitus (particularly after panretinal photocoagulation due to damage to the long ciliary nerves), alcoholism, multiple sclerosis, sarcoidosis.

Evaluation

• Lab tests: VDRL, FTA-ABS.

• Lumbar puncture for VDRL, FTA-ABS, total protein, and cell counts to rule out neurosyphilis.

• Medical consultation.

Prognosis

Pupil abnormality itself is benign; poor for untreated tertiary syphilis.

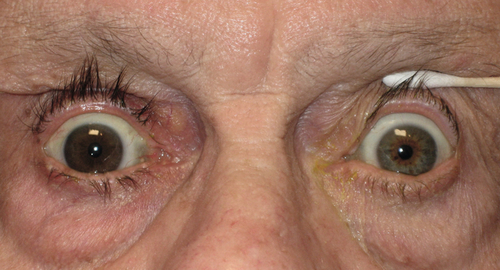

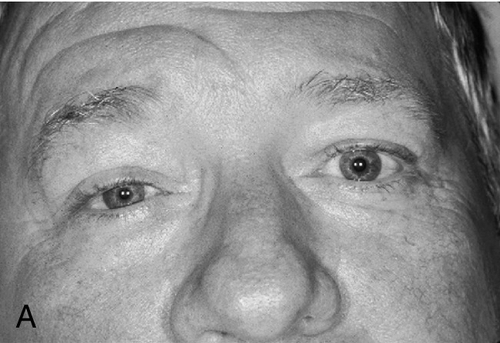

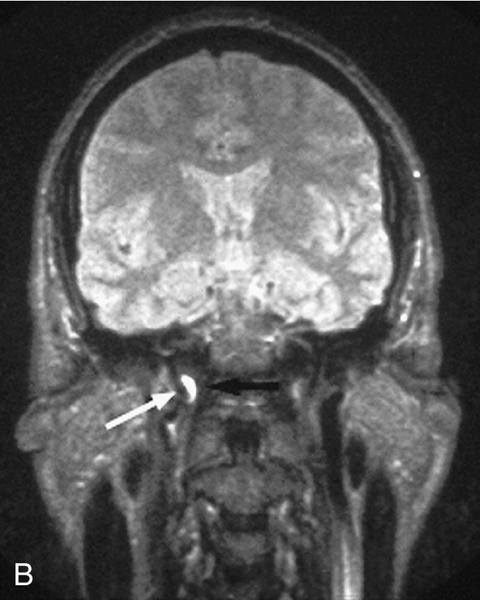

Horner’s Syndrome

Definition

Group of findings that occurs in oculosympathetic paresis. Sympathetic damage may occur anywhere along the three-neuron pathway:

Central (First-Order Neuron)

Hypothalamus to ciliospinal center of Budge (C8–T2).

Preganglionic (Second-Order Neuron)

Spinal cord to superior cervical ganglion.

Postganglionic (Third-Order Neuron)

Along carotid artery to CN V and VI to orbit and finally to iris dilator muscle.

Etiology

Failure of sympathetic nervous system to dilate affected pupil and to stimulate Müller’s muscle in the upper eyelid and smooth muscle fibers of the lower eyelid.

Central

Cerebrovascular accident, neck trauma, tumor, demyelinating disease (rarely causes isolated Horner’s syndrome).

Preganglionic

Pancoast’s tumor, mediastinal mass, cervical rib, neck trauma, abscess, thyroid tumor, after thyroid or neck surgery.

Postganglionic

Neck lesion, head trauma, migraine, cavernous sinus lesion, carotid dissection, carotid–cavernous fistula, internal carotid artery aneurysm, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, vascular disease, infections (complicated otitis media). Congenital Horner’s syndrome is usually due to birth trauma (brachial plexus injury during delivery).

Symptoms

Asymptomatic; may have droopy eyelid, blurred vision, pain (especially with vascular postganglionic etiologies), and other symptoms depending on site and cause of lesion (central usually has other neurologic deficits). Initially, ipsilateral nasal stuffiness may occur.

Signs

Triad of mild (1–2 mm) ptosis, miosis, and anhidrosis (anhidrosis usually indicates preganglionic lesion), anisocoria greater in dark than light (abnormal pupil is smaller and dilates poorly in the dark), upside-down ptosis (lower lid elevation), decreased intraocular pressure (1–2 mmHg lower in the involved eye), in congenital cases heterochromia iridum (iris on involved side is lighter). Initially, ipsilateral conjunctival hyperemia; may have CN VI palsy (localizes the lesion to the cavernous sinus).

Evaluation

• Pharmacologic pupil testing (Note: Testing must be performed before cornea has been manipulated; i.e., before any drops, applanation, or other tests have been performed; otherwise the test result will be invalid):

(2) Topical hydroxyamphetamine 1% (Paredrine): Distinguishes between preganglionic (first-order and second-order neurons) and postganglionic (third-order neuron) lesions (pupil in patient with central or preganglionic Horner’s syndrome dilates equal to normal pupil; pupil in postganglionic Horner’s syndrome does not dilate as well); this test does not determine whether a preganglionic lesion affects the first-order or second-order neuron.

Note: Tests cannot be performed on the same day or will be invalid.

• In an infant with Horner’s syndrome, consider evaluation for neuroblastoma with an MRI of the sympathetic chain from the hypothalamus down to the upper thoracic area and back up the neck to the cavernous sinus and orbit. If positive, additional workup includes checking urine for vanillylmandelic acid and homovanillic acid and further imaging of the abdomen.

• Patients with a central or preganglionic Horner’s syndrome may have neck pain, shoulder pain, or abnormal taste in the mouth or other neurological signs, and should have an MRI of the sympathetic chain.

• Smokers should have a chest radiograph to rule out Pancoast’s tumor.

Prognosis

Depends on etiology; postganglionic lesions are usually benign; most isolated Horner’s syndrome without other findings are benign; preganglionic and central lesions are usually more serious.

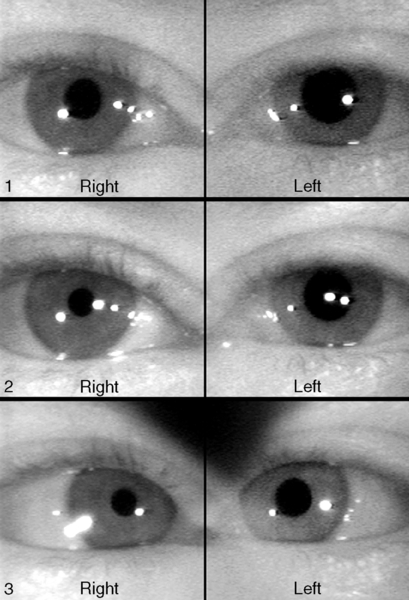

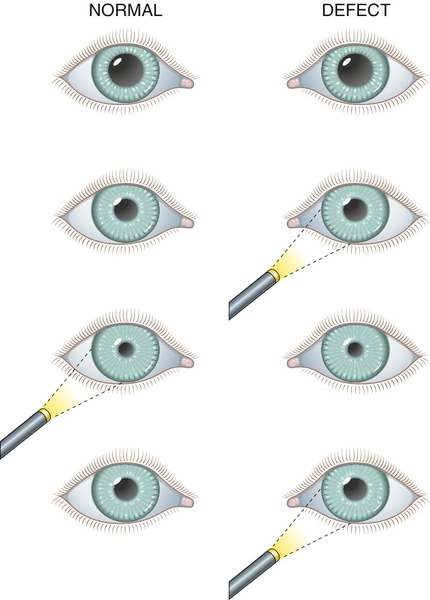

Relative Afferent Pupillary Defect (Marcus Gunn Pupil)

Definition

During the swinging flashlight test (see below), pupillary dilation of the affected eye occurs when the light is on it owing to the relatively lower amount of light perceived by the affected eye compared with the contralateral eye. In other words, the pupil of the affected eye constricts more from the consensual response when the light is on the contralateral eye than from the response from direct light.

Etiology

Asymmetric optic nerve disease or widespread retinal damage; most common causes include any optic neuropathy, optic neuritis, central retinal vein or artery occlusion, and retinal detachment. A mild relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD) may rarely occur with a dense ocular media opacity, including vitreous hemorrhage and cataract (occasionally, a cataract may cause a contralateral RAPD because of light scatter to more retinal area); a very small RAPD may occur with amblyopia; optic tract lesions can cause a contralateral RAPD (due to more nasal crossing fibers in the chiasm).

Symptoms

Decreased vision, dyschromatopsia, diminished sense of brightness.

Signs

RAPD, decreased visual acuity, color vision, and contrast sensitivity; red desaturation; visual field defect; may have swollen or pale optic nerve, or retinal findings. A “reverse” RAPD can be detected even in an eye that is nonreactive because the contralateral eye will constrict more from response to direct light than from the consensual response when the light is on the affected eye.

Differential Diagnosis

Hippus (benign, rhythmic, variation in pupil size; more common in younger individuals).

Evaluation

• Swinging flashlight test: Bright light is shined into one eye and then rapidly into the other in an alternating fashion; positive test result is when the pupil that the light is shined into dilates instead of constricts. When the pupil of the involved eye is nonreactive or nonfunctional, observe the fellow, normal eye for a “reverse” RAPD (dilation when light is on nonreactive eye, constriction when light is shined on reactive eye).

• Grading system with neutral density filters or 1+ to 4+ scale.

Prognosis

Depends on etiology.

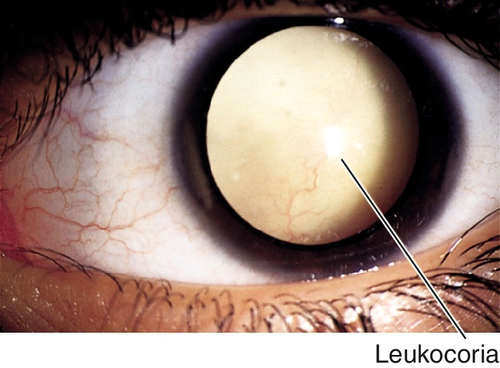

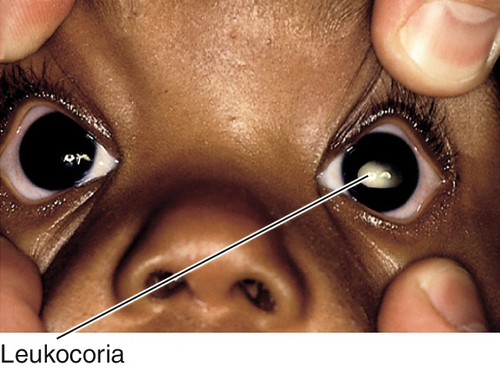

Leukocoria

Definition

Variety of disorders that cause the pupil to appear white; usually noted in infancy or early childhood.

Symptoms

Decreased vision; may notice white pupil, eye turn, or abnormal size of eye.

Signs

Leukocoria, decreased visual acuity; may have RAPD, nystagmus, strabismus, buphthalmos, microphthalmos, anterior chamber cells and flare, increased intraocular pressure, cataract, vitritis, retinal detachment, tumor, or other retinal findings; may have systemic findings.

Differential Diagnosis

Cataract, retinoblastoma, retinopathy of prematurity, persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous, Coats’ disease, toxocariasis, toxoplasmosis, retinal /choroidal /optic nerve coloboma, myelinated nerve fibers, Norrie’s disease, retinal dysplasia, cyclitic membrane, retinal detachment, incontinentia pigmenti, retinoschisis, and medulloepithelioma.

Evaluation

• B-scan ultrasonography to evaluate retrolenticular area, vitreous, and retina if unable to visualize the fundus.

• Consider orbital radiograph, and head and orbital CT scans or MRI to rule out foreign body.

• Pediatric consultation.

Prognosis

Usually poor in the pediatric population; good with surgery if due to a mature white cataract in an adult.

Congenital Anomalies

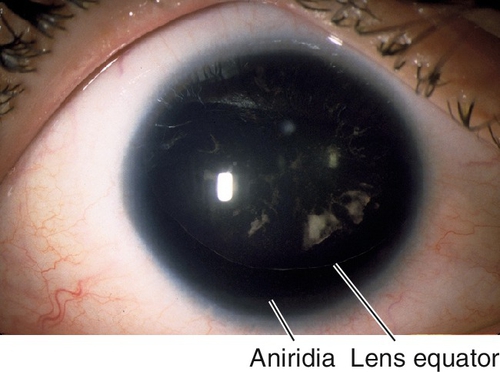

Aniridia

Absence of the iris, except for a small, hypoplastic remnant or stump. Patients also have photophobia, nystagmus, glare, decreased visual acuity, amblyopia, and strabismus; associated with glaucoma in 28–50%, lens opacities in 50–85%, ectopia lentis, corneal pannus, and foveal hypoplasia. Occurs in 1 : 100,000 births; mapped to chromosome 11p. Three forms:

AN 1 (Autosomal Dominant)

Eighty-five percent of cases; only ocular findings.

AN 2

Thirteen percent of cases; includes Miller’s syndrome with both aniridia and Wilms’ tumor, and WAGR (Wilms’ tumor, aniridia, genitourinary abnormalities, and mental retardation). Sporadic, but mapped to chromosome 11p (PAX6 gene).

AN 3 (Autosomal Recessive)

Two percent of cases; associated with mental retardation and cerebellar ataxia (Gillespie’s syndrome); do not develop Wilms’ tumor.

• May require treatment of increased intraocular pressure (see Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma section in Chapter 11).

• May require cyclocryotherapy or glaucoma filtering surgery if medical treatment fails.

• Lensectomy if visually significant cataract develops; consider use of artificial iris segments.

• Consider painted contact lens to decrease photophobia or glare.

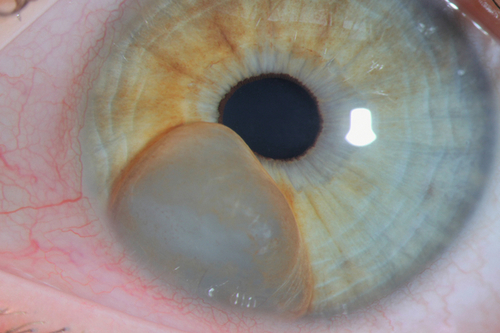

Figure 7-23 Aniridia with entire cataractous lens visible; the inferior edge of the lens is visible.

Coloboma

Iris sector defect due to incomplete closure of the embryonic fissure. Usually located inferiorly; may have other colobomata (lid, lens, retina, choroid, optic nerve); associated with multiple genetic syndromes, including trisomy 22 (cat-eye syndrome), trisomy 18, trisomy 13, and chromosome 18 deletion.

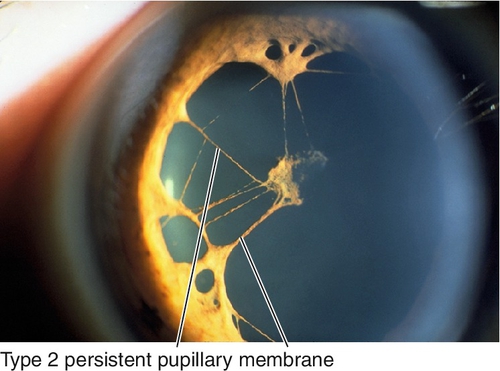

Persistent Pupillary Membrane

Benign, embryonic, mesodermal remnants (tunica vasculosa lentis) that appear as thin iris strands bridging the pupil. Most common ocular congenital anomaly; occurs in up to 80% of dark eyes and 35% of light eyes. Two types:

Type 1

Attached only to the iris.

Type 2

Iridolenticular adhesions.

• If iris strands cross visual axis and are affecting vision, consider Nd : YAG (neodymium : yttrium–aluminum–garnet) laser treatment.

Plateau Iris (Configuration or Syndrome)

Atypical iris configuration (flat contour with steep insertion due to anteriorly rotated ciliary processes; anterior chamber is deep centrally and shallow peripherally). Familial, more common in young, myopic women; 5–8% develop angle-closure glaucoma (plateau iris syndrome) (see Chapter 6).

• May require treatment of increased intraocular pressure (see Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma section in Chapter 11).

• Consider miotic agents (pilocarpine 1% qid) or iridoplasty.

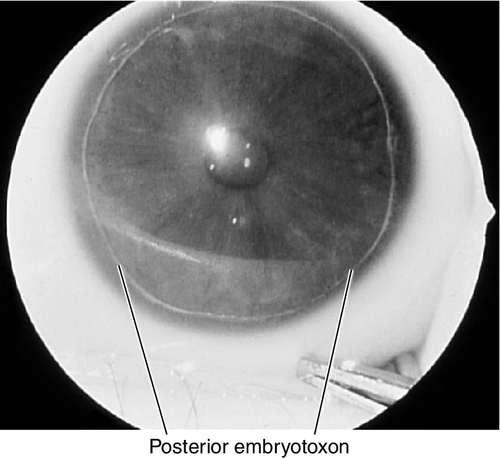

Mesodermal Dysgenesis Syndromes

Definition

Group of bilateral, congenital, hereditary disorders involving anterior segment structures. Originally thought to be due to faulty cleavage of angle structures and, therefore, termed angle-cleavage syndromes.

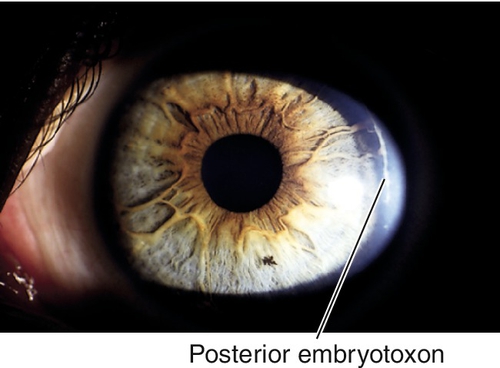

Axenfeld’s Anomaly

Posterior embryotoxon (anteriorly displaced Schwalbe’s line that appears as a prominent, white, corneal line anterior to the limbus; occurs in 15% of normal individuals) and prominent iris processes; associated with secondary glaucoma in 50% of patients. Mapped to chromosome 4q25 (PITX2 gene), 6p25 (FOXC1 gene), 13q14 (RIEG2 gene).

Alagille’s Syndrome

Axenfeld’s anomaly and pigmentary retinopathy, corectopia, esotropia, and systemic abnormalities, including absent deep tendon reflexes, abnormal facies, pulmonic valvar stenosis, peripheral arterial stenosis, and skeletal abnormalities. Abnormal electroretinogram and electro-oculogram. Mapped to chromosome 20p12 (mutation in the JAG1 gene, a NOTCH receptor ligand).

Rieger’s Anomaly

Axenfeld’s anomaly and iris hypoplasia with holes; associated with secondary glaucoma in 50% of patients. Mapped to chromosome 4q25 (PITX2 gene), 6p25 (FOXC1 gene), 13q14 (RIEG2 gene).

Rieger’s Syndrome

Combination of Rieger’s anomaly with mental retardation and systemic abnormalities, including dental, craniofacial, genitourinary, and skeletal problems. Mapped to chromosome 4q25 (PITX2 gene), 6p25 (FOXC1 gene), 13q14 (RIEG2 gene).

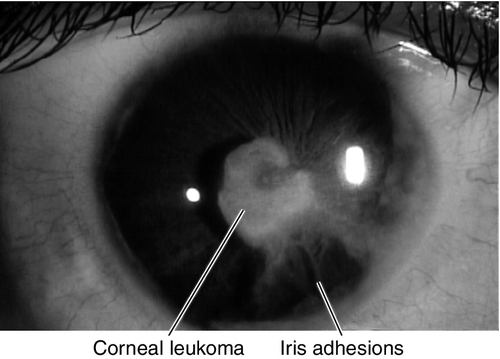

Peters’ Anomaly

Corneal leukoma (white opacity due to central defect in Descemet’s membrane and absence of endothelium) and iris adhesions with or without cataract. Usually sporadic; 80% bilateral; associated with secondary glaucoma in 50% of patients, congenital cardiac defects, cleft lip or palate, craniofacial dysplasia, and skeletal abnormalities. Mapped to chromosome 11p (PAX6 gene).

Symptoms

Asymptomatic; may have decreased vision or iris abnormalities or a white spot on eye.

Signs

Normal or decreased visual acuity, iris and cornea lesions (see above); may have systemic abnormalities and signs of glaucoma, including increased intraocular pressure, optic nerve cupping, and visual field defects.

Differential Diagnosis

Iridocorneal endothelial syndromes, posterior polymorphous dystrophy, aniridia, coloboma, ectopia lentis et pupillae, iridodialysis, iridoschisis, trauma, corneal ulcer, hydrops.

Evaluation

• Check visual fields in patients with elevated intraocular pressure or optic nerve cupping to rule out glaucoma.

• B-scan ultrasonography in Peters’ anomaly if unable to visualize the fundus.

Prognosis

Poor for Peters’ anomaly or when associated with glaucoma; otherwise fair.

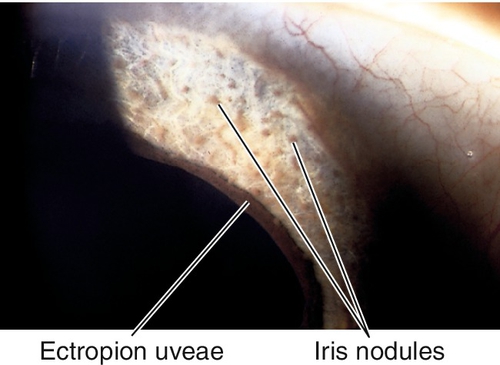

Iridocorneal Endothelial Syndromes

Definition

Unilateral, nonhereditary, slowly progressive abnormality of the corneal endothelium causing a spectrum of diseases with features including corneal edema, iris distortion, and secondary angle-closure glaucoma.

Essential Iris Atrophy (Progressive Iris Atrophy)

Iris atrophy with holes and corectopia, ectropion uveae, and focal stromal effacement.

Chandler’s Syndrome

Variant of essential iris atrophy with mild or no iris changes, corneal edema common, intraocular pressure may not be elevated.

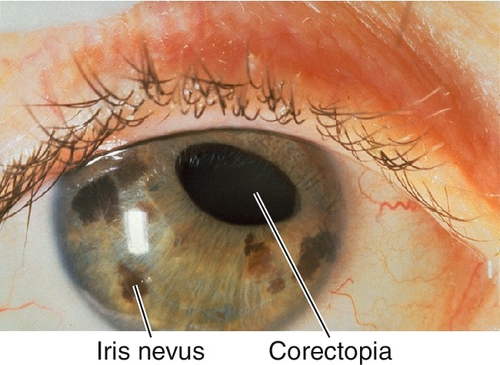

Iris Nevus (Cogan–Reese) Syndrome

Pigmented iris nodules, flattening of iris stroma, pupil abnormalities, and ectropion uveae.

Figure 7-35 Iris nevus (Cogan–Reese) syndrome demonstrating iris nevi, iris atrophy, and corectopia.

Mechanism

Altered, abnormal corneal endothelium proliferates across the angle and onto the iris, forming a membrane that obstructs the trabecular meshwork, distorts the iris, and may form nodules by contracting around the iris stroma.

Epidemiology

Mostly young or middle-aged women; increased risk of secondary angle-closure glaucoma.

Symptoms

Asymptomatic; may have decreased vision, glare, monocular diplopia or polyopia; may notice iris changes.

Signs

Normal or decreased visual acuity, beaten metal appearance of corneal endothelium, corneal edema, increased intraocular pressure, peripheral anterior synechiae, iris changes (see above).

Differential Diagnosis

Posterior polymorphous dystrophy, mesodermal dysgenesis syndromes, Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy, iris nevi or melanoma, aniridia, iridodialysis, iridoschisis, trauma.

Evaluation

• Check visual fields in patients with elevated intraocular pressure or optic nerve cupping to rule out glaucoma.

Prognosis

Chronic, progressive process; poor when associated with glaucoma. Essential iris atrophy and iris nevus syndrome may have worse glaucoma than Chandler’s syndrome.

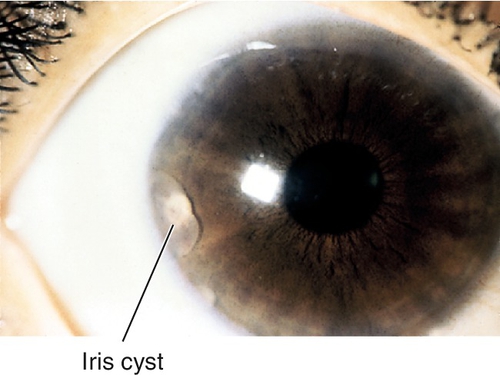

Tumors

Cyst

Can be primary (more common; usually peripheral from stroma or iris pigment epithelium) or secondary (usually due to ingrowth of surface epithelium after trauma or surgery); may cause segmental elevation of iris and angle-closure; rarely detaches and becomes free-floating in anterior chamber; may also form at pupillary margin from long-term use of strong miotic medications. Complications include distortion of pupil, occlusion of visual axis, and secondary glaucoma.

• May require treatment of increased intraocular pressure (see Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma section in Chapter 11).

• Consider surgical excision if vision is affected or secondary glaucoma exists.

Nevus

Single or multiple, flat, pigmented, benign lesions. Pigment spots or freckles occur in 50% of population; rare before 12 years of age. Nevus differentiated from malignant melanoma by size (< 3 mm in diameter), thickness (< 1 mm thick), and the absence of vascularity, ectropion uveae, secondary cataract, secondary glaucoma, and signs of growth.

• Follow for increased intraocular pressure.

• Consider iris fluorescein angiogram to differentiate between nevus and malignant melanoma: nevus has filigree filling pattern that becomes hyperfluorescent early and leaks late or is angiographically silent; malignant melanoma has irregular vessels that fill late.

Nodules

Collections of cells on the iris surface. Several different types:

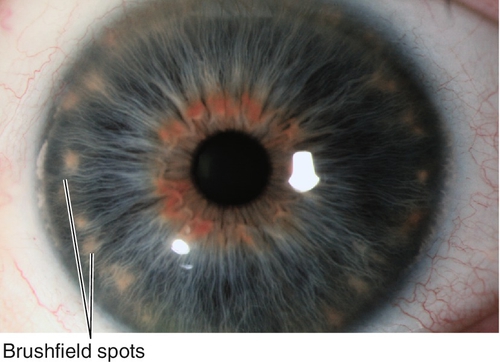

Brushfield Spots

Ring of small, white-gray, peripheral iris spots associated with Down’s syndrome; occurs in 24% of normal individuals (Kunkmann Wolffian bodies).

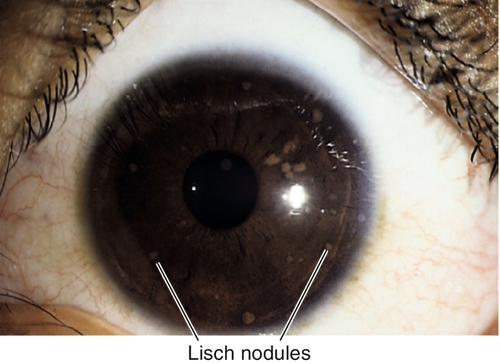

Lisch Nodules

Bilateral, lightly pigmented, gelatinous, melanocytic hamartomas found in 92% of patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1) by age 10; very rare in NF-2; usually involve inferior half of iris; do not involve iris stroma.

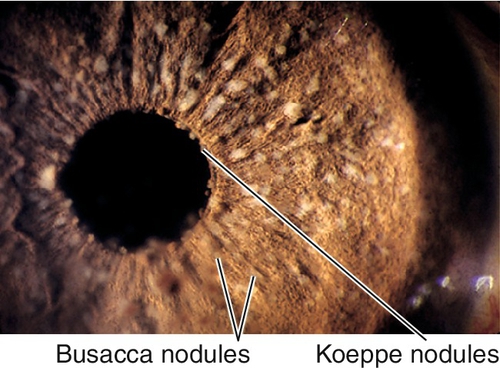

Inflammatory Nodules

Composed of monocytes and inflammatory debris; occurs in granulomatous uveitis. Three types:

Berlin nodules

Nodules in anterior chamber angle.

Busacca nodules

Nodules on anterior iris surface.

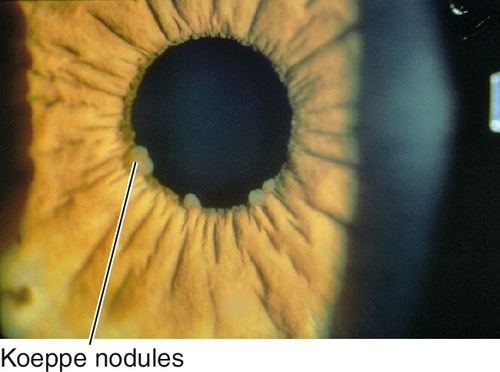

Koeppe nodules

Nodules at pupillary border.

Figure 7-42 Busacca and Koeppe nodules are small, lightly colored collections of inflammatory cells.

Iris Pigment Epithelium Tumors

Very rare tumors of the iris pigment epithelium (adenoma or adenocarcinoma); appear as darkly pigmented, friable nodules.

Juvenile Xanthogranuloma

Yellow iris lesions composed of histiocytes; may bleed, causing spontaneous hyphema.

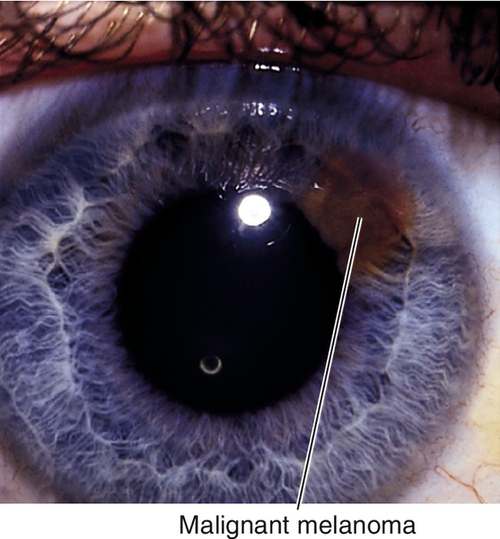

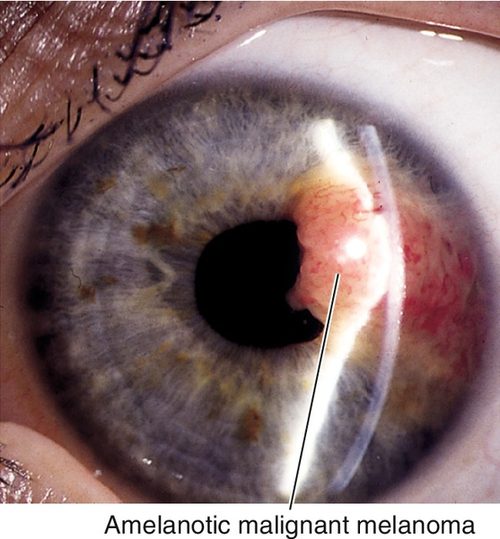

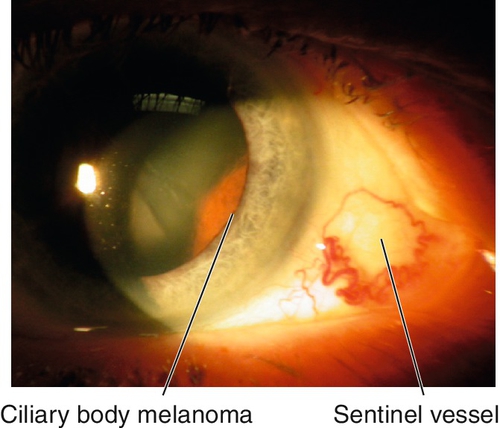

Malignant Melanoma

Dark or amelanotic (pigmentation variable), elevated lesion that usually involves inferior iris and replaces the iris stroma. May be diffuse (associated with heterochromia and secondary glaucoma), tapioca (dark tapioca appearance), ring-shaped, or localized; some have feeder vessels; may involve angle structures; may cause sectoral cataract, hyphema, or secondary glaucoma. One to three percent of all malignant melanomas of the uveal tract involve the iris. Predilection for Caucasians and patients with light irides, rare in African-Americans; many patients have history of nevus that undergoes growth. Prognosis good; 4% mortality.

• Consider B-scan ultrasonography or ultrasound biomicroscopy to rule out ciliary body involvement.

• Treatment with chemotherapy, radiation, surgical excision, and enucleation; should be performed by a tumor specialist.

• May require treatment of increased intraocular pressure (see Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma section in Chapter 11); glaucoma filtering surgery is not recommended.

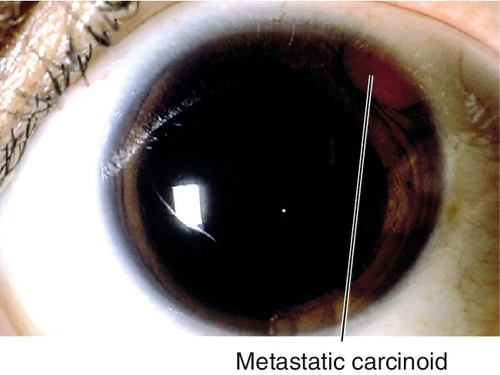

Metastatic Tumors

Rare; usually amelanotic, and from primary carcinoma of the breast, lung, or prostate; often found after primary lesion is discovered.

• May require treatment of increased intraocular pressure (see Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma section in Chapter 11); glaucoma filtering surgery is not recommended.