201 Introduction to Oncologic Emergencies

• Fever in a neutropenic patient with cancer is assumed to be a life-threatening infection; antibiotic therapy must be started immediately.

• Hypercalcemia is common in malignant disease and is often missed. Presenting symptoms may include weakness, vomiting, and mental status changes.

• Tumor lysis syndrome causes acute renal failure, hyperkalemia, hyperphosphatemia, and hypocalcemia; it is a rare but life-threatening complication of chemotherapy.

• Adrenal insufficiency and pericardial tamponade are causes of hypotension.

• Pleural effusions commonly cause dyspnea in the oncology patient. However, always exclude life-threatening causes of dyspnea (e.g., pulmonary embolism, pneumonia, pericardial tamponade) in this patient population.

Epidemiology

As the population ages, cancer prevalence is expected to increase.1 In 2010, the United States population had more than 1.5 million new cancer diagnoses and more than 569,000 cancer deaths.2 The American Cancer Society estimated that the number of new cancer cases will double from 2000 to 2050.1 At the same time, aggressive treatment strategies, whether involving surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation, are helping oncology patients to live longer and at times overcome their cancer. In fact, U.S. cancer death rates decreased by 1% per year from 2001 through 2006.2 Since the 1970s, the 5-year survival rate for all cancers has increased from 50% to 68% in the United States.2 Declines in cancer deaths are the result of many factors, including better screening, early detection strategies, public health risk reduction programs, and improved medical and surgical treatment. Emergency physicians (EPs) are routinely called on to recognize and treat emergency complications of cancer and cancer therapies. Interventions that the EP makes to keep a patient alive acutely may allow the patient’s chemotherapy or radiation therapy to work for an overall cure. Today, oncology patients treated in the emergency department (ED) are increasingly more likely to survive to hospital discharge, even if they are admitted to an intensive care unit.3

Isolation and Infectious Control Issues

Each year, approximately 1.9 million nosocomial infections occur in U.S. hospitals, and approximately 88,000 patients die.4 Immunocompromised patients with cancer, especially neutropenic patients and bone marrow transplant recipients, are at increased risk for these infections. At-risk patients should be identified on ED arrival and should not be allowed to spend a significant amount of time in waiting rooms or busy ED hallways, where they can be exposed to infections from other patients. Ideally, bone marrow transplant recipients and potentially neutropenic patients should be placed in single rooms with positive air pressure at 12 or more air exchanges per hour. Positive air pressure decreases the number of infectious particles that enter a patient’s room. If such a room is unavailable, the next best option is to place the patient in an individual room with the door closed. Patients with a potential airborne illness (e.g., tuberculosis) are the exception; they should be placed in a negative pressure room to protect other patients and the ED staff.

Fever

![]() Facts and Formulas

Facts and Formulas

Neutropenic Fever Defined

Fever: Temperature ≥ 38.3° C once or ≥38.0° C for >1 hour

Neutropenia: Absolute neutrophil count < 500/mm3 or <1000/mm3 with a predicted decline to <500/mm3

Epidemiology

Neutropenic fever is the most common emergency indication for hospital admission among oncology patients. The in-hospital mortality rate in patients with neutropenic fever is approximately 9.5%, and it increases if the patient has any associated comorbidities.5 Patients with neutropenic fever have a mean (median) length of stay of 11.5 (6) days, at a mean cost of more than $19,000 per case.5

Treatment

Empiric, broad-spectrum antibiotics should be started as early as possible for patients in the ED who have neutropenic fever. Antibiotics should not be delayed while awaiting confirmation of the neutropenia but rather should be started on all febrile patients at high risk (e.g., recent chemotherapy).6 Additionally, antibiotics should not be delayed while the EP looks for an infectious source. An obvious source is very often not identifiable in the ED. Rapid antibiotic administration is the likely reason for substantial mortality reductions among bacteremic patients with cancer. With the incorporation of this early antibiotic strategy, a large European research group found an overall mortality decrease from 21% to 7% over a 16-year period.7

Single-agent intravenous antibiotics regimens are currently recommended for hemodynamically stable patients whose medical condition is uncomplicated.6,8 Potential monotherapy regimens include cefepime, piperacillin-tazobactam, or a carbapenem (e.g., imipenem-cilastatin, meropenem).6,8 Double coverage with an aminoglycoside (e.g., gentamicin, tobramycin) or a fluoroquinolone (e.g., levofloxacin) should be considered if antibiotic resistance is strongly suspected, if the patient is in shock, or if this approach is needed to manage other complications. Vancomycin should not be started empirically for neutropenic fever.6,8 No significant difference in morbidity or mortality was found in a meta-analysis of 13 randomized control trials when a standard neutropenic antibiotic regimen was compared with the same regimen plus a glycopeptide (e.g., vancomycin).9 However, one should consider starting vancomycin if the infection is suspected to originate from an indwelling central venous catheter, a soft tissue infection, or hospital-associated pneumonia or if the patient is in septic shock.6,8 A lower threshold for adding vancomycin should be used if the institution has a high rate of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) or resistant viridans streptococcal strains.

Granulocyte colony-stimulating factors (G-CSFs) are used by oncologists with certain chemotherapy regimens to decrease the incidence of neutropenic episodes. Current guidelines recommend the prophylactic administration of a G-CSF with chemotherapy to patients who, based on age, past medical history, chemotherapy toxicity, and tumor characteristics, have a greater than 20% chance of developing febrile neutropenia.8,10 This G-CSF prophylaxis regimen with chemotherapy has been shown to be effective; for example, in patients with small cell lung cancer, it decreases the incidence, duration, and severity of neutropenic fever.11 Commonly used G-CSFs for prophylaxis are daily injections of filgrastim or lenograstim or a once per chemotherapy cycle injection of pegfilgrastim. Adverse side effects of G-CSF use include bone, joint and musculoskeletal pain and flulike symptoms.12

The use of a G-CSF in the acute setting of neutropenic fever is controversial. A meta-analysis of 13 studies with 1518 patients found that patients with neutropenic fever who were treated with G-CSFs had shorter hospitalizations and neutrophil recovery times but only a marginally significant benefit in infection-related mortality and no significant benefit in overall mortality.12 Because the effects of G-CSFs on mortality are not clear and because these agents are very expensive, a G-CSF should not be given routinely in the ED for neutropenic fever. Rather, until more convincing evidence exists, G-CSFs should be given only after discussion with the patient’s oncologist and considered only for patients who are at high risk for infectious complications or who have prognostic factors predictive of a poor outcome.10,13

Follow-Up and Next Steps

Nearly all patients with neutropenic fever require admission. Outpatient management could be considered for carefully selected low-risk patients within a well-designed institutional protocol and in concert with the patient’s oncologist. Certain decision rules have attempted to determine which neutropenic patients are at low risk for complications and therefore could be eligible for outpatient treatment with oral antibiotics. The most commonly cited decision rule for assessing low-risk patients is the Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC) index score6,8 (Table 201.1). In its initial validation study, the MASCC index score was found to have a positive predictive value of 91%, a specificity of 68%, and a sensitivity of 71%.14 The MASCC decision rule is likely best applied to select patients who can quickly undergo conversion to oral antibiotics as inpatients and, in the absence of early complications, be targeted for early hospital discharge. If the patient is discharged, an oral antibiotic regimen is prescribed; ideally, the patient is observed taking the first dose in the ED. The two most common regimens used are a quinolone alone (e.g., ciprofloxacin) or a quinolone plus amoxicillin-clavulanate.15

Table 201.1 Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer Index Score for Identifying Low-Risk Patients at Neutropenic Fever

| BURDEN OF ILLNESS* | SCORE |

|---|---|

| No or mild symptoms/moderate symptoms* | 5/3 |

| No hypotension | 5 |

| No chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 4 |

| Solid tumor or no previous fungal infection | 4 |

| No dehydration | 3 |

| Outpatient status† | 3 |

| Age < 60 yr | 2 |

| Add together points to obtain score (maximum score, 26) | |

| Risk of complication: high risk < 21; low risk ≥ 21 | |

* Burden of illness: 5 for no or mild, 3 for moderate, 0 for severe.

† Outpatient status means onset of fever as an outpatient.

From Klastersky J, Paesmans M, Rubenstein EB, Boyer M. The Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer Risk Index: a multinational scoring system for identifying low-risk febrile neutropenic cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 2000;18:3038-51.

Infectious Causes of Fever Unique to the Patient with Cancer

Neutropenic Enterocolitis (Typhlitis)

Typhlitis (neutropenic enterocolitis) is an inflammatory process of the ileum and colon that affects neutropenic patients. Typhlitis is most commonly associated with acute leukemia, but it can be seen with other malignant conditions. Typhlitis usually occurs in patients undergoing chemotherapy, although it occasionally occurs in patients who are not. Presenting clinical symptoms may include fever, lower abdominal pain, and diarrhea, which can be bloody or watery. Other potential symptoms include abdominal distention and nausea or vomiting. On physical examination, the patient’s abdomen may be generally tender, or the tenderness may be localized to the right lower quadrant. CT scan can make the diagnosis and rule out other potentially dangerous abdominal processes (e.g., appendicitis, diverticulitis). Typical CT scan findings of typhlitis are diffuse submucosal thickening of the affected bowel wall, generally the terminal ileum or ascending colon. Other CT scan findings may include paracolonic fluid and gas in the bowel wall. Uncomplicated cases should be treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics (covering aerobic and anaerobic pathogens, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa), bowel rest, and supportive care. Patients who present with perforation, obstruction, bleeding, or gangrenous bowel require prompt surgical consultation. The mortality rate of typhlitis is quite high; in one case series, six of nine patients died of sepsis.16

Fungal Infections

Fungal infections increasingly are the likely source of the infection when neutropenic patients with cancer have persistent fevers despite ongoing broad-spectrum antibiotics. Candida albicans is the most common fungal pathogen in these cases, but aspergillosis, cryptococcus, and other fungal infections can occur. In oncology patients with neutropenic fever, invasive candidiasis and aspergillosis are associated with high mortality rates (36.7% and 39.2%, respectively).5 Patients with leukemia, in particular, have increasing incidences of fungal infections, especially with Candida species. Empiric antifungal therapy should be considered in neutropenic patients with persistent fever despite 4 to 7 days of antibiotic therapy.8

Electrolyte Disturbances in the Oncology Patient

Tumor Lysis Syndrome

Perspective

Tumor lysis syndrome (TLS) is the constellation of metabolic abnormalities that occur in response to the rapid destruction of malignant cells, generally from the initiation of chemotherapy (Table 201.2). The sudden death of many malignant cells results in the release into the bloodstream of their intracellular contents, and this causes sudden increases in potassium, phosphorus, and uric acid levels. TLS is generally predictable. It usually occurs with the initiation of chemotherapy in a patient with newly diagnosed cancer. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (especially Burkitt lymphoma) are the most common cancers associated with TLS.17 Less commonly, TLS occurs in other leukemias, in multiple myeloma, or after the treatment of some solid tumors such as breast and lung cancer. When initiating chemotherapy, oncologists generally take measures to prevent TLS in at-risk patients by pretreatment with aggressive hydration, diuresis, and allopurinol (in an attempt to decrease uric acid formation). Rarely, TLS develops spontaneously. When it does, it is usually in the setting of relapsing or newly diagnosed (but untreated) cancer.

Table 201.2 Tumor Lysis Syndrome: Electrolyte Disturbances and Treatment

| DISTURBANCE | TREATMENT |

|---|---|

| Hyperkalemia | Sodium polystyrene sulfonate, regular insulin and glucose, calcium gluconate; if severe: dialysis |

| Hyperphosphatemia | Aluminum hydroxide; if severe: dialysis |

| Hypocalcemia | Calcium gluconate (only if symptomatic) |

| Uremia | IV hydration; IV rasburicase (recombinant urate oxidase) |

| Renal failure | Dialysis |

IV, Intravenous.

Treatment

Hyperkalemia and hyperphosphatemia should be promptly treated. Only symptomatic hypocalcemia should be treated because infusing calcium into a hyperphosphatemic patient increases the risk of calcium phosphate formation and deposition throughout the body, including in the renal tubules. In clinically significant TLS (e.g., renal dysfunction, hyperuricemia), rasburicase, a recombinant form of urate oxidase, can be used. Urate oxidase is an enzyme (not found in humans) that converts uric acid to allantoin, which is 5 to 10 times more water soluble than uric acid. The recommended rasburicase dose is 0.1 to 0.2 mg/kg/day intravenously in 50 mL of normal saline solution over 30 minutes.17 Rasburicase is contraindicated in patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. Allopurinol, which has been traditionally used in the prevention and treatment of TLS, works by decreasing uric acid production through competitive inhibition of the enzyme xanthine oxidase, which turns xanthine into uric acid. Once uric acid is present, allopurinol’s effect is limited; therefore, allopurinol is not very useful in the acute treatment of TLS.17 Finally, when renal failure develops and becomes severe (e.g., uncontrolled hyperkalemia, uncontrolled hypertension, fluid overload), emergency hemodialysis is indicated.

Controversy exists regarding the practice of urine alkalinization, which consists of adding sodium bicarbonate to intravenous fluids in an effort to help excrete uric acid. The theory is that alkalinization (with a goal of achieving a urine pH of 7 to 7.5) decreases uric acid precipitation in the renal tubules and increases uric acid excretion in the form of urate. Although a sodium bicarbonate infusion may help to eliminate uric acid, it may also worsen hypocalcemia and increase phosphate and calcium precipitation, potentially in the heart and kidneys, and therefore worsen renal function. Because hydration alone may achieve adequate uric acid excretion, routine urine alkalinization is not currently recommended.17

Hypercalcemia

Epidemiology

Hypercalcemia is the most common metabolic abnormality found in patients with cancer. At some point in their illness, at least 10% to 30% of patients with cancer develop hypercalcemia.18 Unfortunately, the diagnosis is frequently missed and left untreated because the symptoms are nonspecific and are often attributed to other causes (e.g., chemotherapy, infection). Hypercalcemia is most commonly found in breast and lung cancer, but it also occurs in multiple myeloma, leukemias, lymphomas, and cancers of the head, neck, kidney, and gastrointestinal tract.18

Treatment

Correcting hypercalcemia not only improves symptoms, but it also may decrease the risk of death during hospitalization.19 For initial treatment of significant hypercalcemia, aggressive intravenous hydration with normal saline solution should be started. Hypercalcemic patients may be significantly volume depleted and require intravenous fluids. Saline hydration dilutes the calcium concentration, promotes urinary excretion of calcium, and treats dehydration. Patients with severe hypercalcemia should be placed on continuous cardiac monitoring, and their urine output should be closely monitored (with a Foley catheter if necessary).

In addition to saline hydration, a bisphosphonate should be considered (e.g., pamidronate, zoledronic). Bisphosphonates work by inhibiting osteoclastic activity through prevention of osteoclast attachment to bone and interference with osteoclast recruitment; this process decreases bone reabsorption. Pamidronate, the most commonly used bisphosphonate, can be administered at 60 mg intravenously over 2 to 24 hours for moderate hypercalcemia and at 90 mg over 2 to 24 hours for severe hypercalcemia. Another bisphosphonate, zoledronic acid, 4 mg intravenously, may be more effective.20

Hypotension

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

The causes of hypotension or shock in an oncology patient in the ED vary to some degree from those seen in the general ED population (Box 201.1). Common causes of hypotension and shock, such as sepsis and hypovolemia (e.g., secondary to gastrointestinal losses or bleeding), are also common in the oncology patient. Severe dehydration is a particular problem because many cancers or cancer treatments make oral intake very difficult and may cause vomiting or diarrhea. Certain clinical entities such as pericardial tamponade and adrenal insufficiency appear with increased frequency in this patient population. Cardiac tamponade is discussed in Chapter 202, but the EP must always consider this disorder in any patient with cancer who presents with hypotension, shock, or dyspnea. Some causes of hypotension are unique to the patient with cancer, such as myocardial dysfunction from a chemotherapeutic agent (e.g., doxorubicin). Because oncology patients are immunocompromised at baseline, they may require more intensive management and may suffer a worse outcome if hypotension is not addressed promptly.

Adrenal Insufficiency

Pathophysiology

In the oncology patient, adrenal insufficiency is most commonly a result of previous treatment with high-dose steroids used in chemotherapy protocols. Many patients with cancer may have subclinical or mild adrenal insufficiency that is not asymptomatic until a significant stress (e.g., infection, dehydration) develops. Adrenal insufficiency can be primary if the adrenal glands are destroyed in some way (e.g., hemorrhage, infarction) or secondary if dysfunction of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis causes a deficiency of adrenocorticotropic hormone. Previous exogenous steroid use is a secondary cause. Metastatic infiltration of the adrenal glands is not uncommon because of the adrenal’s rich blood supply; however, metastatic infiltration rarely causes adrenal insufficiency. In one study, only 4.3% (20 of 464) of patients with metastasis to the adrenal glands on CT scan had or developed symptomatic adrenal insufficiency before they died.21 Metastasis to the adrenal glands is most common in lung cancer, gastrointestinal malignant disease (stomach, esophagus, liver, pancreas, and bile duct), lymphoma, kidney cancer, and breast cancer.21

Diagnostic Testing

According to consensus guidelines, adrenal insufficiency (in the setting of critical illness) can be diagnosed with either a random total cortisol level of less than 10 mcg/dL or by cortisol level nonresponse (less than 9 mcg/dL) to the 250-mcg short corticotropin-stimulation test.22 The short corticotropin-stimulation test can be performed by administering 250 mcg of cosyntropin intravenously after a baseline cortisol level is obtained. The cortisol level is repeated 30 and 60 minutes later. If the patient has adrenal insufficiency, the cortisol level response will be less than 9 mcg/dL (the difference between the baseline level and the highest response).23 In an effort to increase the sensitivity of detecting adrenal insufficiency, the corticotropin-stimulation test with 1 mcg was studied, but further outcome data are needed.24 If etomidate, which selectively inhibits 11-β-hydroxylase, is used in the ED course (specifically in the previous 4 hours), it may interfere with the cortisol response to corticotrophin. This may give a false-positive result to the corticotropin-stimulation test and the clinician may falsely conclude that the patient is adrenally suppressed.25

Myocardial Dysfunction Secondary to Chemotherapy

As in the general population, the most common cause of cardiac dysfunction or cardiogenic shock in the oncology population is coronary artery disease. Oncology patients, like any other patient who presents in congestive heart failure or cardiogenic shock, must be evaluated for myocardial infarction. However, a few chemotherapeutic agents, most notably the anthracyclines, can cause cardiomyopathies and congestive heart failure (Table 201.3). A newer drug, trastuzumab (Herceptin), which is a recombinant monoclonal antibody used in the treatment of breast cancer, has been associated with reductions in left ventricular ejection fraction and episodes of congestive heart failure.26

| AGENT OR DRUG CLASS | TOXICITY |

|---|---|

| Anthracyclines (e.g., doxorubicin, daunorubicin, epirubicin, idarubicin) |

Myocardial cell death, fibrosis, left ventricular dysfunction, CHF |

| Mitoxantrone (drug class: anthracenedione) | Cardiomyopathy similar to that caused by anthracyclines |

| 5-Fluorouracil | Coronary vasospasm or ischemia |

| Cyclophosphamide | Acute hemorrhagic myopericarditis |

| Trastuzumab (Herceptin) | Decrease in left ventricular ejection fraction, CHF |

| Taxanes (paclitaxel, docetaxel)* | Dysrhythmias (atrial or ventricular), bradycardia |

| Radiation therapy (to lung, breast, or mediastinum) | Coronary artery disease, chronic pericarditis, valvular disease, dysrhythmias |

CHF, Congestive heart failure.

Dyspnea and Airway Issues in the Oncology Patient

Malignant Pleural Effusions

Treatment

Thoracentesis should be performed for highly symptomatic patients. Removing pleural fluid may provide instant relief; however, some patients may not respond. Unfortunately, the reaccumulation rate after thoracentesis alone is nearly 100% at 1 month.27 Traditionally, a blind approach was incorporated. Bedside ultrasound scanning makes this procedure much simpler and safer. If thoracentesis is performed for the first presentation of pleural effusion, the fluid should be sent for cytologic study because it may prove useful diagnostically. In general, unless a pleural effusion must be tapped for diagnostic purposes or to provide symptomatic relief, no need exists to tap the effusion in the ED. A chest radiograph should be performed at the completion of the procedure, to ensure that pneumothorax has not developed. More definitive treatment of the pleural effusion should be coordinated by the patient’s oncologist and will be tailored based on the patient’s prognosis, severity of symptoms, and type of malignant disease. Multiple treatment options exist, including supplemental oxygen, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, chemical pleurodesis, and long-term indwelling pleural catheter placement.

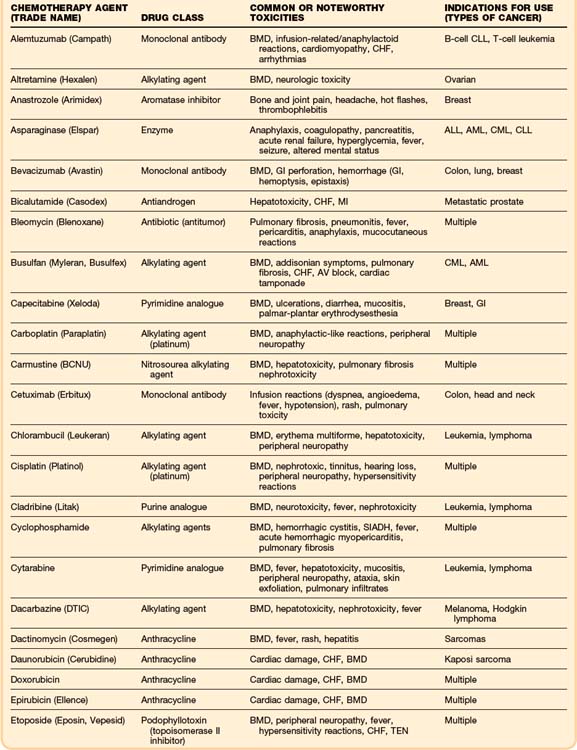

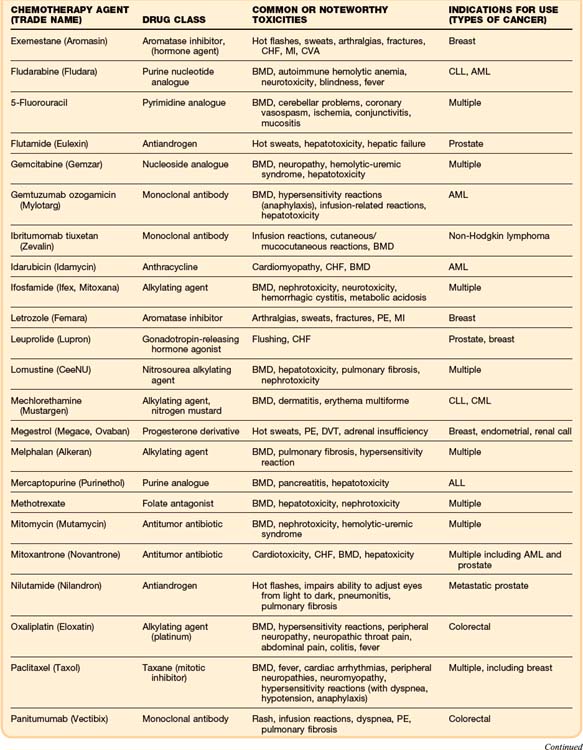

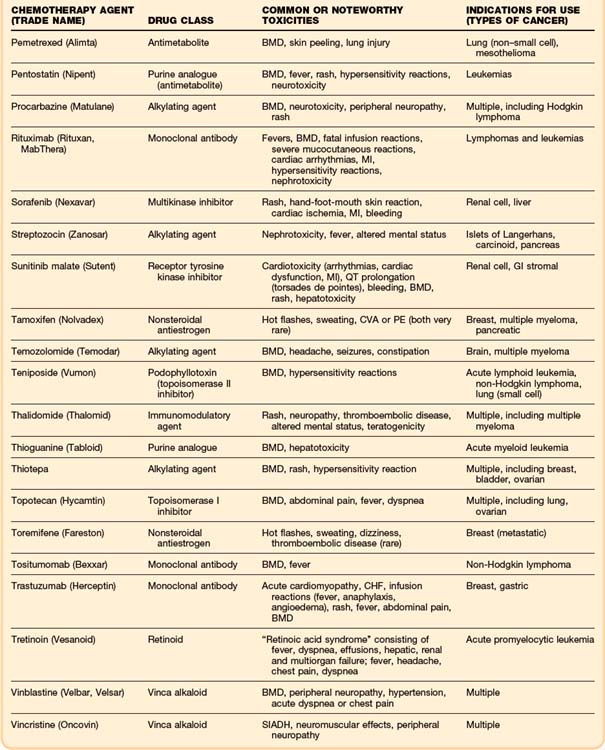

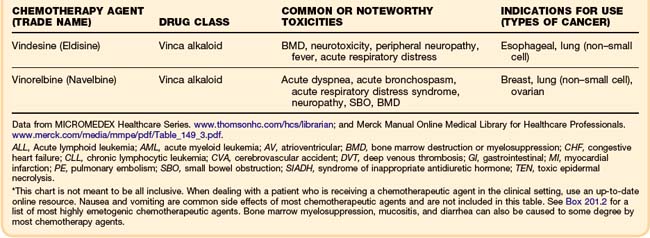

Emergency Side Effects of Oncology Treatment

Although some chemotherapeutic agents have unique side effects (Table 201.4), a few side effects are more universal. Bone marrow depression is a very common side effect of most agents. Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and mucositis are also quite common. The severity of these symptoms varies, depending on the particular chemotherapy agent.

Global Issues

Pain

Pain in the oncology patient may represent an acute process, the progression of disease, or inadequate outpatient treatment. In a survey of physicians directly involved in cancer care (oncologists, hematologists, surgeons, and radiation therapists), 86% believed that most of their patients with cancer-related pain were being undermedicated, and 76% reported performing poor pain assessments for their patients.28 After potentially dangerous or reversible causes of pain have been ruled out and the patient’s pain is under control, usually in response to high doses of intravenous narcotics, a plan for outpatient pain control should be created with the patient and in consultation with the patient’s oncologist. Oncologists tend to use an escalating approach to outpatient pain management, starting with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, then weaker opioids (e.g., codeine), and finally stronger opioids (e.g., morphine, fentanyl). Some physicians question this escalating approach, especially in advanced cancer, and instead start with small doses of stronger opioids and titrate upward as needed. Because the pain in patients with cancer is ongoing, pain medication with longer half-lives or continuous action, such as very-long-acting oral opioids or a transdermal opiate patch, is preferred. Additional short-acting medications should be provided for breakthrough pain; breakthrough dosing often needs to be 10% to 20% of the patient’s 24-hour total opiate dose. A new or escalating-dose opioid prescription should be accompanied by a prescription for a laxative because constipation is the most common side effect of opioid therapy.

Nausea and Vomiting

Nausea and vomiting, of all the side effects of chemotherapy, are often considered the worst adverse effects. Occasionally, nausea and vomiting can be severe enough to cause patients to discontinue their treatment. Poor antiemetic control with previous chemotherapy, female sex, low alcohol intake, and younger age are all associated with a higher risk of emesis after chemotherapy.29 In an effort to reduce the risk of emesis and to increase the tolerability of the treatment, chemotherapy regimens usually include an antiemetic drug. Chemotherapeutic agents with the highest emetogenic potential are listed in Box 201.2.30

Box 201.2

Chemotherapeutic Agents with the Highest Emetogenic Potential*

From Schwartzberg L, Szabo S, Gilmore J, et al. Likelihood of a subsequent chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) event in patients receiving low, moderately or highly emetogenic chemotherapy (LEC/MEC/HEC). Curr Med Res Opin 2011;27:837-45.

Mucositis

Pathophysiology

Mucositis is inflammation and ulceration of the mucous membranes, and it occurs in up to 58% of patients with cancer, depending on their diagnosis.31 Mucositis most commonly manifests in the mouth, but it can occur anywhere in the gastrointestinal, genitourinary, or respiratory tracts. Because mucositis is a breakdown of the normal integrity of mucous membranes, it is associated with an increased risk of infection. Oral mucositis is a side effect of chemotherapy or radiation, or it can result from certain cancers, such as oral cancers and leukemia. Patients obtaining either radiation for head and neck cancers or chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil, anthracyclines, or irinotecan and patients who are bone marrow transplant recipients have high rates of mucositis (Fig. 201.1).

Treatment

Patients who present to the ED with oral mucositis should be given proper pain control, which may include the use of opiates. Any secondary infections, such as oral candidiasis or herpes simplex, should be treated. A bland, soft diet is recommended, as well as ice chips or other cold products to keep the oral mucosa moist. Special attention to oral hygiene is essential for at-risk patients with cancer, including the use of a soft toothbrush, frequent saline or baking soda rinses, prophylactic anticandidal rinses (e.g., nystatin), and adequate general nutrition. Optimal mucositis treatment is still in question and requires further research. Protocols vary at different institutions. A 2010 Cochrane systematic review did not find any high-level evidence-based treatment options.32 Although not an ED option, low-level laser therapy was the only potentially useful intervention found in two or more clinical trials.32

Coiffier B, Altman A, Pui CH, et al. Guidelines for the management of pediatric and adult tumor lysis syndrome: an evidence-based review. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2767–2778.

Freifeld AG, Bow EJ, Sepkowitz KA, et al. Executive summary: clinical practice guideline for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer. 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:427–431.

Santarpia L, Koch CA, Sarlis NJ. Hypercalcemia in cancer patients: pathobiology and management. Horm Metab Res. 2010;42:153–164.

Tam CS, O’Reilly M, Andresen D, et al. Use of empiric antimicrobial therapy in neutropenic fever. Intern Med J. 2011;41:90–101.

1 Edwards BK, Howe HL, Ries LA, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1973-1999, featuring implications of age and aging on US cancer burden. Cancer. 2002;94:2766–2792.

2 Kris MG, Benowitz SI, Adams S, et al. Clinical cancer advances 2010: annual report on progress against cancer from the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:5327–5347.

3 McGrath S, Chatterjee F, Whiteley C, Osterman M. ICU and 6-month outcome of oncology patients in the intensive care unit. Q J Med. 2010;103:397–403.

4 Weinstein RA. Nosocomial infection update. Emerg Infect Dis. 1998;4:416–420.

5 Kuderer NM, Dale DC, Crawford J, et al. Mortality, morbidity, and cost associated with febrile neutropenia in adult cancer patients. Cancer. 2006;106:2258–2266.

6 Tam CS, O’Reilly M, Andresen D, et al. Use of empiric antimicrobial therapy in neutropenic fever. Intern Med J. 2011;41:90–101.

7 Viscoli C, Castagnola E. Planned progressive antimicrobial therapy in neutropenic patients. Br J Haematol. 1998;102:879–888.

8 Freifeld AG, Bow EJ, Sepkowitz KA, et al. Executive summary: clinical practice guideline for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer. 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:427–431.

9 Paul M, Borok S, Fraser A, et al. Additional anti–gram-positive antibiotic treatment for febrile neutropenic cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 3, 2005. CD003914

10 Smith TJ, Khatcheressian J, Lyman GH, et al. 2006 Update on recommendations for the use of white blood cell growth factors: an evidence-based clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3187–3205.

11 Crawford J, Ozer H, Stoller R. Reduction by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor of fever and neutropenia induced by chemotherapy in patients with small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:164–170.

12 Clark O, Djulbegovic B, Dale DC, et al. Treatment with colony-stimulating factors improves clinical outcomes in patients with established febrile neutropenia: a meta-analysis of the randomized clinical trials [abstract 689]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2003;22:172.

13 Aapro M, Crawford J, Kamioner D. Prophylaxis of chemotherapy-induced febrile neutropenia with granulocyte colony-stimulating factors: where are we now? Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:529–541.

14 Klastersky J, Paesmans M, Rubenstein EB, Boyer M. The Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer Risk Index: a multinational scoring system for identifying low-risk febrile neutropenic cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3038–3051.

15 Vidal L, Paul M, Ben Dor I, et al. Oral versus intravenous antibiotic treatment for febrile neutropenia in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;54:29–37.

16 Hsu TF, Huang HH, Yen DH, et al. ED presentation of neutropenic enterocolitis in adult patients with acute leukemia. Am J Emerg Med. 2004;22:276–279.

17 Coiffier B, Altman A, Pui CH, et al. Guidelines for the management of pediatric and adult tumor lysis syndrome: an evidence-based review. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2767–2778.

18 Santarpia L, Koch CA, Sarlis NJ. Hypercalcemia in cancer patients: pathobiology and management. Horm Metab Res. 2010;42:153–164.

19 Lamy O, Jenzer-Closuit A, Burckhardt P. Hypercalcemia of malignancy: an undiagnosed and undertreated disease. J Intern Med. 2001;250:73–79.

20 Major P, Lortholary A, Hon J, et al. Zoledronic acid is superior to pamidronate in the treatment of hypercalcemia of malignancy: a pooled analysis of two randomized, controlled clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:558–567.

21 Lam KY, Lo CY. Metastatic tumours of the adrenal glands: a 30-year experience in a teaching hospital. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2002;56:95–101.

22 Marik PE, Pastores SM, Annane D, et al. Recommendations for the diagnosis and management of corticosteroid insufficiency in critically ill adult patients: consensus statements from an international task force by the American College of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:1937–1949.

23 Annane D, Sebille V, Charpentier C, et al. Effect of treatment with low doses of hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone on mortality in patients with septic shock. JAMA. 2002;288:862–871.

24 Siraux V, De Backer D, Yalavatti G, et al. Relative adrenal insufficiency in patients with septic shock: comparison of low-dose and conventional corticotropin tests. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:2479–2486.

25 Schenarts CL, Burton JH, Riker RR, et al. Adrenocortical dysfunction following etomidate induction in emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8:1–7.

26 Murray S. Trastuzumab (Herceptin) and HER2-positive breast cancer. CMAJ. 2006;174:36–37.

27 Antunes G, Neville DuffyJ, et al. BTS guidelines for the management of malignant pleural effusions. Thorax. 2003;58(suppl 2):ii29–ii38.

28 Von Roenn JH, Cleeland CS, Gonin R, et al. Physician attitudes and practice in cancer pain management: a survey from the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:121–126.

29 Hesketh PJ. Defining the emetogenicity of cancer chemotherapy regimens: relevance to clinical practice. Oncologist. 1999;4:191–196.

30 Schwartzberg L, Szabo S, Gilmore J, et al. Likelihood of a subsequent chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) event in patients receiving low, moderately or highly emetogenic chemotherapy (LEC/MEC/HEC). Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27:837–845.

31 Sonis ST, Elting LS, Keefe D, et al. Perspectives on cancer therapy–induced mucosal injury: pathogenesis, measurement, epidemiology, and consequences for patients. Cancer. 2004;100:1995–2025.

32 Clarkson JE, Worthington HV, Furness S, et al. Interventions for treating oral mucositis for patients with cancer receiving treatment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 12, 2010. CD000978