Chapter 21 Introduction: Comorbid Disorders and Special Populations

Comorbid Conditions

Over the years, a large number of disorders or other conditions have been suggested to be associated with restless legs syndrome (RLS) (see Chapter 16, Box 16-2). The evidence for some is stronger than that for others, but these associations indicate that many different medical specialists need to be concerned about RLS (Table 21-1). Many of these conditions share an association with depleted iron stores—iron deficiency and anemia, kidney failure, pregnancy, rheumatoid arthritis—but others cannot yet be explained on the basis of a single pathophysiologic diathesis. An intriguing question, now that specific genetic variants associated with RLS have been reported (see Chapter 8), is whether these same variants will be associated with increased risk of RLS in these comorbid conditions.

TABLE 21-1 Specialties Important for Comorbid Restless Legs Syndrome

| Specialty | Disorder or Condition |

|---|---|

| Neurology | Neuropathy |

| Radiculopathy | |

| Parkinson’s disease | |

| Hematology | Anemia |

| Iron deficiency | |

| Nephrology | Renal failure |

| Obstetrics/gynecology | Pregnancy |

| Rheumatology | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| Sjögren’s syndrome | |

| Scleroderma | |

| Fibromyalgia | |

| Psychiatry | Depression |

| Neuroleptic therapy | |

| Antidepressant therapy | |

| Pediatrics | Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder “growing pains” |

| Endocrinology | Diabetes |

| Thyroid disorders | |

| Gastroenterology | Gastric resection |

| Malabsorption | |

| Gastrointestinal cancer with blood loss |

Polyneuropathies and Other Lower Motor Neuron Diseases

Ondo and Jankovic1 reported that 15 of 41 patients with RLS had electrodiagnostic evidence of polyneuropathy or radiculopathy, although only 7 of these 15 patients showed clinical signs of neuropathy. In an early systematic study, Rutkove and colleagues2 studied a consecutive series of patients with polyneuropathy and documented only a 5% frequency of RLS, which is similar to what is found in the general population. Studies have found a greater frequency of RLS in diabetic neuropathy and polyneuropathy (see Chapter 27). RLS may also be particularly prevalent in certain types of neuropathies, such as cryoglobulinemic or familial amyloid polyneuropathy. Newer studies have more decisively implicated the polyneuropathies and diabetic neuropathy as associated with RLS. Gemignani anc coworkers3 in a series of 44 consecutive patients with Charcot-Marie-Tooth (CMT) disease found RLS in 10 of 27 CMT type 2 patients (37%) with prominent sensory symptoms and in none of the patients with CMT type 1, suggesting a role for sensory (afferent) input in the pathogenesis of RLS. Certain studies found morphological evidence of subtle nerve damage. Sural nerve biopsy4 findings in 7 of 8 patients with primary RLS were consistent with an axonal neuropathy, and skin punch biopsy5 in the legs documented evidence of subclinical small fiber neuropathy in 8 of 22 patients (36%) with primary RLS. There may be other explanations for these subtle morphological changes, such as age-related changes in the sural and skin nerves and trauma caused by vigorous rubbing of the legs, resulting from an urge to move and rub to get relief from the discomforting urge to do so. It is not clear why some patients with polyneuropathy or lumbosacral radiculopathy develop symptoms of RLS, whereas many patients with polyneuropathies or other lower motor neuron disorders do not develop RLS. Sometimes motor neuron disease has been mistaken for RLS, but the diffuse fasciculations, muscle weakness, wasting, and presence of upper motor neuron manifestations should simplify the differentiation.

Anemia and Restless Legs Syndrome

There have been isolated reports of iron, cobalamin (vitamin B12), and folate deficiency causing secondary RLS. The strongest evidence is for iron deficiency. Ekbom,6 in his original description, mentioned iron deficiency with low serum iron in 25% of his cases. Nordlander7 in 1953 reported resolution of RLS symptoms in over 90% of subjects after intravenous iron infusion. The iron deficiency theory for RLS was revived after a long hiatus by O’Keefe and colleagues8 in 1994, who reported low iron, measured by serum ferritin levels in RLS patients. Subsequent elegant studies by the Johns Hopkins group of investigators9–15 firmly established the role of iron in its pathogenesis and therapy (see Chapters 9, 10, and 34). Iron is needed as a cofactor for tyrosine hydroxylase, the rate-limiting enzyme in the synthesis of dopamine; therefore, iron deficiency may interfere with the normal production of dopamine. Furthermore, the D2 receptor is an iron-containing protein and hence, iron deficiency may impair the normal function of D2 receptors. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)14 study of the brain and limited pathological15 findings in RLS patients clearly established brain iron acquisition and storage problem deficiencies in the substantia nigra of these patients. The appearance of RLS symptoms after multiple blood donations16,17 associated with iron deficiency anemia, low serum hemoglobin and ferritin levels, and improvement after iron supplementation also clearly supports the role of iron deficiency in the pathogenesis of RLS. Reports of failure18,19 to find a significant difference in serum iron indices or hemoglobin between patients with RLS and control subjects with renal failure and pregnancy as well as a single report20 of a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial of iron supplementation failing to show any significant difference in RLS symptoms with treatment point to the incompleteness of the iron deficiency theory. RLS appears to be a heterogeneous syndrome with several subtypes associated with different neurobiological mechanisms.

End-Stage Renal Disease and Hemodialysis

There is an increased prevalence of RLS (20% to 50% or even higher) with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) on dialysis18,21–24 (see Chapter 25). RLS in ESRD and idiopathic RLS are clinically or therapeutically quite similar. Whether the risk factor is comorbidity with ESRD or dialysis or both is not known, but most of the reports of RLS are in patients on hemodialysis. There are reports of increased mortality and morbidity in RLS patients on dialysis.21,25–27 No conclusive biochemical risk factors are specifically associated with RLS except for low iron status as a predictor of poor outcome. Report of disappearance of RLS after kidney transplantation28 suggests that some unknown biochemical or other factors are causing the ESRD RLS symptoms.

Pregnancy and Restless Legs Syndrome

Ekbom6 in his original description of RLS reported higher prevalence of RLS symptoms in pregnant women. Subsequent epidemiologic studies (not a population survey) found that approximately 19% to 27% of pregnant women have RLS symptoms, most prominently in the last trimester of pregnancy29–31 (see Chapter 23). In some pregnant women with previously diagnosed RLS symptoms, the symptoms worsened during pregnancy, but in the majority, symptoms appeared for the first time during pregnancy with subsequent resolution of symptoms around the time of delivery. In a small minority, symptoms persisted after delivery suggesting that pregnancy might trigger RLS in those who are genetically predisposed to develop RLS. Long-term follow-up studies of pregnant RLS patients to determine the natural history of this subtype of RLS are not available. Using a structured clinical interview and IRLSSG diagnostic criteria Manconi and colleagues31 studied 642 pregnant women at the time of delivery and one, three, and six months after delivery. They noted a 26.6% prevalence of RLS amongst these women with resolution of symptoms after delivery. In a previous study, Lee and coworkers19 gave a figure of 23% of pregnant women with RLS. These authors found reduced serum ferritin at preconception and low folate levels both during preconception and pregnancy. In a survey of 300 RLS patients, Winkelmann and associates32 noted worsening of the previous RLS symptoms or the onset of RLS symptoms for the first time during pregnancy in both familial and sporadic RLS but more frequently in the familial than sporadic patients. Several factors have been postulated to be responsible for the exacerbation or occurrence of RLS symptoms during pregnancy, such as iron and folate deficiencies, hormonal changes (e.g., increased levels of estrogen, progesterone, prolactin) and mechanical factors causing lower limb vascular congestion.

Rheumatoid Arthritis and Restless Legs Syndrome

There are two reports33,34 of increased prevalence of RLS in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (25% to 30%). In contrast, Banno and colleagues,35 in their questionnaire survey of 218 patients with a diagnosis of RLS, and Ondo and colleagues,36 measuring rheumatologic serologies in 68 RLS patients, did not find increased prevalence of RLS in rheumatoid arthritis.

Restless Legs Syndrome and Parkinson’s Disease

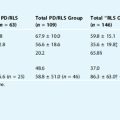

The prevalence studies of RLS in Parkinson’s disease (PD) are few and somewhat contradictory (see Chapter 26). Earlier reports of RLS in PD may have been cases of akathisia in PD. From pharmacologic and neuroimaging points of view, there is a link between RLS and PD. Both PD and RLS patients benefit from dopaminergic treatment, although RLS patients need much less dopaminergic medication than PD patients. Neuroimaging studies of the brain (positron emission tomography and single-photon emission computed tomography) show a mild striatal dysfunction in RLS37–39 in contrast to severe nigrostriatal degeneration in PD. Special MRI study14 of the brain in RLS shows evidence of decreased iron storage in the substantia nigra of RLS patients, whereas PD patients have increased iron. Limited neuropathological studies15 suggest no dopaminergic neuronal degeneration in RLS and, therefore, neuronal dysfunction or degeneration in diencephalospinal dopamine system may be important in RLS pathophysiology.

Earlier reports by Ekbom,40 Strang,41 and Lang and Johnson42 showed no increased prevalence rate of RLS in PD. A study by Tan and coworkers43 confirmed these earlier observations. On the other hand, Ondo and associates44 found a prevalence of 20.8% in the PD population in their clinic in Houston, Texas, and Krishnan and associates.45 in a case-control study noted increased prevalence of RLS in a PD population in New Delhi, India. It should be noted, however, that there is no good epidemiologic study comparing a large number of age- and sex-matched control subjects and PD patients to show the prevalence of PD in RLS and in RLS patients who later developed PD.

Pulmonary Disease, Restless Legs Syndrome, and Sleep Apnea

Spillane46 described RLS in eight patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). I noted an association between RLS and sleep apnea in three COPD patients.47 Schönbrunn and coworkers48 also mentioned an association between RLS and sleep apnea. These three studies, however, were conducted before the Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group (IRLSSG) criteria were established for the clinical diagnosis of RLS. In a study by Lakshminarayanan and colleagues49 in 60 sequentially studied patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) diagnosed by polysomnography (respiratory disturbance index of more than 10), the authors found a prevalence of RLS in 8.3% of their patients. This figure is, however, not dissimilar to the prevalence figure for RLS, although spouses serving as age-matched control subjects showed a prevalence figure of 2.5%. Delgado Rodrigues and coworkers50 observed improvements in sleep apnea and RLS symptoms in 17 patients with coexistent RLS and OSAS following nasal continuous positive airway pressure titration. It is possible that chronic hypoxemia caused by COPD and nocturnal hypoxemia caused by OSAS played roles in the pathogenesis of RLS in these patients. The association of RLS, COPD, and OSAS remains uncertain until good epidemiologic studies in the general population are performed.

Drugs and Restless Legs Syndrome

In scattered case reports and anecdotally, several antidepressants (e.g., tricyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs]), neuroleptics, dopamine antagonists, antihistamines (mostly H1 antagonists), and lithium have been shown to cause or worsen RLS symptoms51,52 (see also Chapter 28). Berger53 noted a 27% prevalence of RLS in a highly selective population in a single practice who were treated with tricyclic antipressants and SSRIs. He further observed that 75% of RLS patients had a history of regular intake of nonopioid analgesics and he suggested that the intake of analgesics enhanced the risk for RLS. Leutgeb and Martus54 previously also reported a prevalence rate of 27% in a selective population with anxiety and affective disorders on antidepressant medications who had previously taken analgesics including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs). These authors postulated that neither antidepressants nor neuroleptics, but nonopioid analgesics seemed to be a major risk factor of RLS. The role of antidepressant medications causing or exaggerating RLS symptoms, thus, remains controversial. In a report after a retrospective chart review of 200 consecutive patients referred to their sleep disorder center for evaluation of sleep-onset insomnia, Brown and colleagues55 concluded that there was no statistical association between RLS and antidepressant medications.

Other Miscellaneous Conditions Associated With Restless Legs Syndrome

There are some scattered case reports of RLS associated with varicose veins, thrombophlebitis, hyperthyroidism,56 hypothyroidism,56,57 hyperparathyroidism,58 meralgia paresthetica,59 saphenous nerve entrapment,60 multiple sclerosis, myelopathies, Isaac syndrome, stiff-man syndrome, and hyperekplexia.51 Reports of RLS in patients with cancer or following gastric surgery may have been secondary to anemia and/or polyneuropathy.51

1. Ondo W, Jankovic J. Restless legs syndrome: Clinicoetiologic correlates. Neurology. 1996;47:1435-1441.

2. Rutkove SB, Matheson JK, Logigian EL. Restless legs syndrome in patients with polyneuropathy. Muscle Nerve. 1996;19:670-672.

3. Gemignani F, Marbini A, Di Giovanni G, et al. Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2 with restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 1999;52:1064-1066.

4. Iannaccone S, Zucconi M, Marchettini P, et al. Evidence of peripheral axonal neuropathy in primary restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord. 1995;10:2-9.

5. Polydefkis M, Allen RP, Hauer P, et al. Subclinical sensory neuropathy in late-onset restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 2000;55:1115-1121.

6. Ekbom KA. Restless legs: A clinical study. Acta Med Scand Suppl. 1945;158:1-123.

7. Nordlander NB. Therapy in restless legs. Acta Med Scand. 1953;145:453-457.

8. O’Keeffe ST, Gavin K, Lavan JN. Iron status and restless legs syndrome in the elderly. Age Ageing. 1994;23:200-203.

9. Sun ER, Chen CA, Ho G, et al. Iron and the restless legs syndrome. Sleep. 1998;21:371-377.

10. Allen RP, Earley CJ. Restless legs syndrome: A review of clinical and pathophysiologic features. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;18:128-147.

11. Allen R. Dopamine and iron in the pathophysiology of restless legs syndrome (RLS). Sleep Med. 2004;5:385-391.

12. Earley CJ, Heckler D, Allen RP. The treatment of restless legs syndrome with intravenous iron dextran. Sleep Med. 2004;5:231-235.

13. Earley CJ, Connor JR, Beard JL, et al. Ferritin levels in the cerebrospinal fluid and restless legs syndrome: Effects of different clinical phenotypes. Sleep. 2005;28:1069-1075.

14. Allen RP, Barker PB, Wehrl F, et al. MRI measurement of brain iron in patients with restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 2001;56:263-265.

15. Connor JR, Boyer PJ, Menzies SL, et al. Neuropathological examination suggests impaired brain iron acquisition in restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 2003;61:304-309.

16. Silber MH, Richardson JW. Multiple blood donations associated with iron deficiency in patients with restless legs syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78:52-54.

17. Ulfberg J, Nystrom B. Restless legs syndrome in blood donors. Sleep Med. 2004;5:115-118.

18. Collado-Seidel V, Kohnen R, Samtleben W, et al. Clinical and biochemical findings in uremic patients with and without restless legs syndrome. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;31:324-328.

19. Lee KA, Zaffke ME, Baratte-Beebe K. Restless legs syndrome and sleep disturbance during pregnancy: The role of folate and iron. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2001;10:335-341.

20. Davis BJ, Rajput A, Rajput ML, et al. A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of iron in restless legs syndrome. Eur Neurol. 2000;43:70-75.

21. Winkelman JW, Chertow GM, Lazarus JM. Restless legs syndrome in end-stage renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 1996;28:372-378.

22. Siddiqui S, Kavanagh D, Traynor J, et al. risk factors for restless legs syndrome in dialysis patients. Nephron Clin Pract. 2005;101:c155-c160.

23. Hui DS, Wong TY, Ko FW, et al. Prevalence of sleep disturbances in Chinese patients with end-stage renal failure on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;36:783-788.

24. Kutner N, Bliwise D. Restless legs complaint in African-American and Caucasian hemodialysis patients. Sleep Med. 2002;3:497-500.

25. Unruh ML, Levey AS, D’Ambrosio C, et al. Restless legs symptoms among incident dialysis patients: Association with lower quality of life and shorter survival. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:900-909.

26. Kalantar-Zadeh K, McAllister CJ, Lehn RS, et al. A low serum iron level is a predictor of poor outcome in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:671-684.

27. Kalanter-Zadeh K, Regidor DL, McAllister CJ, et al. Time-dependent association between indices of iron store and mortality in hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005.

28. Winkelmann J, Stautner A, Samtleben W, et al. Long-term course of restless legs syndrome in dialysis patients after kidney transplantation. Mov Disord. 2002;17:1072-1076.

29. Goodman JD, Brodie C, Ayida GA. Restless leg syndrome in pregnancy. BMJ. 1988;297:1101-1102.

30. Suzuki K, Ohida T, Sone T, et al. The prevalence of restless legs syndrome among pregnant women in Japan and the relationship between restless legs syndrome and sleep problems. Sleep. 2003;26:673-677.

31. Manconi M, Govoni V, De Vito A, et al. Pregnancy as a risk factor for restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2004;5:305-308.

32. Winkelmann J, Wetter TC, Collado-Seidel V, et al. Clinical characteristics and frequency of the hereditary restless legs syndrome in a population of 300 patients. Sleep. 2000;23:591-594.

33. Salih AM, Gray RE, Mills KR, et al. A clinical, serological and neurophysiological study of restless legs syndrome in rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1994;33:60-63.

34. Reynolds G, Blake DR, Pall HS, et al. Restless legs syndrome and rheumatioid arthritis. Br Med J Clin Res Ed. 1986;292:659-660.

35. Banno K, Delaive K, Walld R, et al. Restless legs syndrome in 218 patients: Associated disorders. Sleep Med. 2000;1:221-229.

36. Ondo W, Tan EK, Mansoor J. Rheumatologic serologies in secondary restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord. 2000;15:321-323.

37. Ruottinen HM, Partinen M, Hublin C, et al. An FDOPA PET study in patients with periodic limb movement disorder and restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 2000;54:502-504.

38. Turjanski N, Lees AJ, Brooks DJ. Striatal dopaminergic function in restless legs syndrome: 18F-dopa and 11C-raclopride PET studies. Neurology. 1999;52:932-937.

39. Michaud M, Soucy JP, Chabli A, et al. SPECT imaging of striatal pre- and postsynaptic dopaminergic status in restless legs syndrome with periodic leg movements in sleep. J Neurol. 2002;249:164-170.

40. Ekbom KA. Restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 1960;10:868-873.

41. Strang PR. The symptoms of restless legs. Med J Aust. 1967;1:1211-1213.

42. Lang AE, Johnson K. Akathisia in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 1987;37:477-481.

43. Tan EK, Lum SY, Wong MC. Restless legs syndrome in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Sci. 2002;196:33-36.

44. Ondo WG, Vuong KD, Jankovic J. Exploring the relationship between Parkinson disease and restless legs syndrome. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:421-424.

45. Krishnan PR, Bhatia M, Behari M. Restless legs syndrome in Parkinson’s disease: A case-controlled study. Mov Disord. 2003;18:181-185.

46. Spillane JD. Restless legs syndrome in chronic pulmonary disease. Br Med J. 1970;4:796-798.

47. Chokroverty S, Sachdeo R. Restless limb-myoclonus sleep apnea syndrome [abstract]. Ann Neurol. 1984;16:124A.

48. Schönbrunn E, Riemann D, Hohagen F, Berger M. Restless legs and sleep apnea syndrome—random coincidence or causal relation? Nervenarzt. 1990;61:306-311.

49. Lakshminarayanan S, Paramasivan KD, Walters AS, et al. Clinically significant but unsuspected restless legs syndrome in patients with sleep apnea. Mov Disord. 2005;20:501-503.

50. Delgado Rodrigues RN, Alvim de Abreu E Silva, Rodrigues AA, Pratesi R, Krieger J. Outcome of restless legs severity after continuous positive air pressure (CPAP) treatment in patients affected by the association of RLS and obstructive sleep apneas. Sleep Med. 2006;7:235-239.

51. Hening W, Allen R, Walters A, et al. Motor functions and dysfunctions of sleep. In: Chokroverty S, editor. Sleep Disorders Medicine: Basic Science, Technical Considerations and Clinical Aspects. Boston: Butterworth; 1999:441-507.

52. Lesage S, Hening WA. The restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder: A review of management. Semin Neurol. 2004;24:249-259.

53. Berger K. Non-opioid analgesics and the risk of restless legs syndrome—A spurious association? Sleep Med. 2003;4:351-352.

54. Leutgeb U, Martus P. Regular intake of non-opioid analgesics is associated with an increased risk of restless legs syndrome in patients maintained on antidepressants. Eur J Med Res. 2002;7:368-378.

55. Brown LK, Dedrick DL, Doggett JW, et al. Antidepressant medication use and restless legs syndrome in patients presenting with insomnia. Sleep Med. 2005;6:443-450.

56. Tan EK, Ho SC, Eng P, et al. Restless legs symptoms in thyroid disorders. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2004;10:149-151.

57. Bon E, Rolland Y, Laroche M, et al. Hypothyroidism on Colchimax revealed by restless legs syndrome. Rev Rheum Engl Ed. 1996;63:304.

58. Lim LL, Dinner D, Tham KW, et al. Restless legs syndrome associated with primary hyperparathyroidism. Sleep Med. 2005;6:283-285.

59. Ekbom KA. Restless legs. JAMA. 1946;131:481.

60. Lewis F. The role of the saphenous nerve in insomnia: a proposed etiology of restless legs syndrome. Med Hypotheses. 1991;34:331-333.