Intravenous Regional Anesthesia*

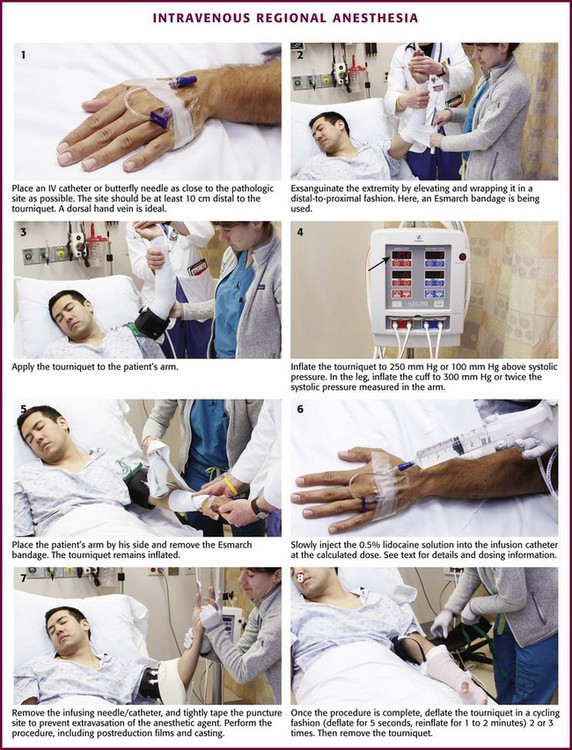

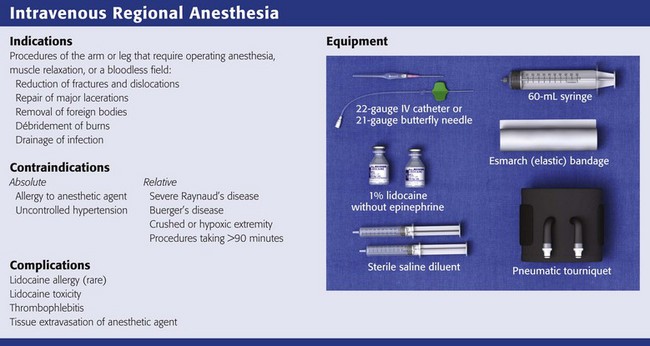

Review Box 32-1 Intravenous regional anesthesia: indications, contraindications, complications, and equipment. A double cuff tourniquet is shown. Not shown is a device required to provide continuous cuff pressure (see Fig. 32-2). Do not use a standard blood pressure cuff.

Clinical use of intravenous regional anesthesia (IVRA) has been well established as a safe,1–3 quick, and effective alternative to general anesthesia in selected cases requiring surgical manipulation of the upper and lower extremities. Though historically relegated to the operating room, the procedure is readily applicable to outpatient use. Because of its reliability, safety, and ease of use, it is now commonly used in the emergency department (ED) and clinic. In the ED, the technique provides quick and complete anesthesia, muscle relaxation, and a bloodless operating field. The procedure is free from the troublesome side effects associated with other regional blocks, such as the axillary block. The procedure is easily mastered and has a very low failure rate; consistently good results can be expected. Although not a standard requirement of ED personnel, this technique can be safely used by trained ED clinicians, including physician’s assistants and nurse practitioners, and does not have to be administered by an anesthesiologist.3 The first practical use of analgesia associated with the intravenous (IV) injection of a local anesthetic agent was described by August Gustav Bier in 1908.4 Colbern has since proposed the eponym Bier block.5 Although the procedure has been in existence for many years, the need for special equipment and a safe anesthetic agent limited its use. However, the Bier block has now gained wide acceptance as a safe and effective procedure, and several papers extol its virtues.6–9 Even though complications do exist, no reported fatalities directly attributable to use of the Bier block with lidocaine have been reported. In this chapter the techniques and complications are discussed according to their application in the ED.

Indications and Contraindications

Indications for IVRA include any procedure on the arm or leg that requires operating anesthesia, muscle relaxation, or a bloodless field, such as reduction of fractures and dislocations, repair of major lacerations, removal of foreign bodies, débridement of burns, and drainage of infection (Fig. 32-1). IVRA is commonly used for extremity surgery, such as carpal tunnel surgery or tendon repair. The procedure may be carried out on any patient of any age who is able to cooperate with the clinician.

Equipment

The equipment required for IVRA consists of the following:

• 1% lidocaine (Xylocaine),* without epinephrine, to be diluted to a 0.5% solution (note: 1% lidocaine = 10 mg/mL; hence 1 mL of 1% lidocaine = 10 mg)

• Clonidine, a parenteral opioid such as fentanyl, or ketorolac if used as additives

• Sterile saline solution as a diluent

• 50-mL syringe/18-gauge needle

• Pneumatic tourniquet (single or double cuff) such as the Zimmer A.T.S. 2000 Automatic Tourniquet System (Fig. 32-2) (Note: Do not use a standard blood pressure cuff.)

• IV catheters (20 or 22 gauge) or a 21-gauge butterfly needle

• Elastic bandage/Webril padding

• 500 mL of 5% dextrose in water (D5W) and IV extension tubing (optional)

Procedure

While the patient is being prepared, keep the lidocaine solution ready, but withhold it until the injured extremity is exsanguinated and the cuff is in place and inflated, as discussed later. The standard dose of lidocaine for the arm is 3 mg/kg. Inject it as a 0.5% solution (1% lidocaine mixed with equal parts sterile saline in a 50-mL syringe). Hence, for a 70-kg patient, infuse 210 mg of lidocaine (21 mL of 1% lidocaine) mixed with 21 mL of saline for a total volume in the infusing syringe of 42 mL of 0.5% lidocaine. Farrell and coworkers described a procedure termed the minidose Bier block in which 1.5 mg/kg of lidocaine is used and reported a 95% success rate.10 This lower dose may decrease the incidence of central nervous system side effects and is more desirable in the ED setting. Additional lidocaine may be infused if the initial dose is inadequate. Lidocaine with epinephrine should not be used. Plain lidocaine is also available as a 0.5% solution and can therefore be used directly to avoid diluting the stronger solution. Some prefer preservative-free lidocaine, but most clinicians use standard lidocaine with preservatives.

Premix the anesthetic and saline solution in the syringe. Inflate the tourniquet and place a plastic catheter or a metal butterfly needle in a superficial vein as close to the pathologic site as possible, and securely tape it in place (Fig. 32-3, step 1). It is usually desirable to use a vein on the dorsum of the hand, but importantly, the injection site should be at least 10 cm distal to the tourniquet to avoid injection of anesthetic proximal to or under the tourniquet. Keep the hub on the catheter to avoid backbleeding, or attach the syringe to the butterfly tubing. This catheter will be the route of injection of the anesthetic agent. Anesthesia from a fingertip-to-elbow direction seems to occur irrespective of the site of infusion of the anesthetic, but selecting an injection location near the site of pathology may provide more rapid anesthesia at a lower dosage.

Deflate the tourniquet used to obtain IV access, and exsanguinate the extremity so that when the anesthetic agent is injected, it will fill the drained vascular system. Exsanguination may be accomplished by either of two methods. Simple elevation of the extremity for a few minutes may be adequate, but wrapping the extremity in a distal-to-proximal direction with an elastic or Esmarch bandage, while being careful to not dislodge the infusion needle, significantly enhances exsanguination (see Fig. 32-3, step 2). Wrapping may be painful, so this step can be eliminated if it causes too much anxiety for the patient. If the wrapping procedure is not done, the extremity should be elevated for at least 3 minutes. During the wrapping procedure, care must be taken to not dislodge or infiltrate the infusion catheter.

With the extremity still elevated or wrapped, the tourniquet is inflated to 250 mm Hg (or 100 mm Hg above systolic pressure), the arm is placed by the patient’s side, and the elastic exsanguination bandage is removed (see Fig. 32-3, steps 3 to 5). In a child the tourniquet is inflated to 50 mm Hg above systolic pressure. In elderly obese patients with calcified peripheral vessels, arterial occlusion may not be achieved safely.11 In the leg, cuff pressure of 300 mm Hg or approximately twice the systolic pressure measured in the arms is suggested.

With the tourniquet now inflated, slowly inject the 0.5% lidocaine solution into the infusion catheter at the calculated dose (see Fig. 32-3, step 6). Note that the solution is placed in the arm in which the circulation is blocked, not in the precautionary keep-open IV line on the unaffected side. At this point, blotchy areas of erythema may appear on the skin. This is not an adverse reaction to the anesthetic agent but merely the result of residual blood being displaced from the vascular compartment, and it heralds success of the procedure.

In 3 to 5 minutes, the patient will experience paresthesia or warmth beginning in the fingertips and traveling proximally, with final anesthesia occurring above the elbow, to the level of the tourniquet. Complete anesthesia ensues in 10 to 20 minutes, followed by muscle relaxation. Note that adequate analgesia may exist even if the patient can still sense touch and position and has some motor function. If the “minidose” technique (initial dose of 1.5 mg/kg of lidocaine) does not provide adequate anesthesia, infuse an additional 0.5 to 1 mg/kg of diluted lidocaine at this time. As an example, for a 70-kg patient, an additional 0.5 mg/kg of lidocaine equals 35 mg lidocaine (3.5 mL of 1% lidocaine), and when the 1% lidocaine is diluted equally with saline, the final volume of the additional 0.5% lidocaine is 7 mL. Additional lidocaine was required in 7% of cases in one series in which the minidose regimen was used.10 The clinician should be patient, however, and wait a full 15 minutes before infusing additional lidocaine. Alternatively, if analgesia is slow or inadequate, an extra 10 to 20 mL of saline solution may be injected to supplement the total volume of solution to enhance the effect. Do not exceed a 3-mg/kg total dose of lidocaine. For obese patients, a maximum of 300 mg of lidocaine is suggested for the arm and no more than 400 mg for the leg. Data for very obese patients do not exist. Next, withdraw the infusing needle and tightly tape the puncture site to prevent extravasation of the anesthetic agent. Perform the surgical procedure or manipulation, including postreduction x-ray films and casting or bandaging (see Fig. 32-3, step 7).

Sensation returns quickly when the tourniquet is removed, and in 5 to 10 minutes the extremity returns to its pre-anesthetic level of sensation and function. Many patients describe a transient intense tingling sensation after cuff deflation. If the procedure takes longer than 20 or 30 minutes, many patients complain of pain from the tourniquet because it is not inflated over an anesthetized area. Use of a double-cuff tourniquet may alleviate the problem of pain under the cuff. A wide tourniquet cuff (14 cm) is less painful than a narrow tourniquet (7 cm) when the cuff is inflated 10 mm Hg above loss the of arterial pulse.12 The reason for pain under the tourniquet is unknown, but this can be a limiting factor because most patients begin to feel significant discomfort after 30 minutes if only a single cuff is used. Tourniquet pain can be significantly reduced and tourniquet time extended by adding ketorolac to the lidocaine anesthetic (see later).

After 45 to 60 minutes of observation, the patient may be discharged (Box 32-1). Observation time depends on the use of other medications, procedural difficulties, and overall assessment of the patient. There are no standard or specific postprocedure instructions, but precautions similar to those given for conscious sedation are reasonable. Driving is best prohibited for 6 to 8 hours, and the patient should leave with a responsible adult. Delayed complications from lidocaine have not been reported.

Mechanism of Action

Some of the anesthesia is undoubtedly related to the ischemia produced by the tourniquet, but most of the anesthesia is secondary to the anesthetic agent itself. Although the exact mechanism by which anesthesia is produced is unknown, the site of action of the anesthetic may be at sensory nerve endings, neuromuscular junctions, or major nerve trunks.13 Contrast-enhanced studies have demonstrated that the anesthetic agent does not diffuse throughout the entire arm, yet anesthesia of the entire limb is obtained. For example, when the anesthetic agent is injected into the elbow and kept in that region with both distal and proximal tourniquets, anesthesia of the entire arm develops.14 Evidence indicates that the local anesthetic does not simply diffuse from the venous system into tissue but travels via vascular channels directly inside the nerve. Regardless of where the anesthetic is infused, the fingertips are the first area to experience anesthesia, thus suggesting that the core of the nerve is in contact with the anesthetic agent initially. After release of the tourniquet, a considerable amount of the drug still remains in the injected limb for at least 1 hour.15 This would suggest that at least a portion of the anesthetic leaves the vascular compartment and becomes fixed in tissue.

Procedural Points

Use of 0.5% plain lidocaine at a dose of 1.5 to 3 mg/kg is preferred for the upper extremity. A similar dose may be used in the leg if a calf tourniquet is used. For procedures in the leg, using a thigh cuff, 150 mL of 0.25% lidocaine (375 mg) has been used. The greater volume can augment drug distribution in the larger lower extremity. Other agents have been used without demonstrable advantage and are not recommended.16 Bupivacaine (Marcaine, Sensorcaine) is contraindicated because of the potential for serious cardiovascular and neurologic complications.17,18

Some authors have suggested the use of IV ketorolac (60 mg) or clonidine (0.15 mg if the IV preparation is available) in addition to the lidocaine.19,20 These additives are mixed with the lidocaine and injected into the operative arm. Both have been shown to be safe, and they decrease the need for postoperative analgesics and antiemetics. Tourniquet time is prolonged with these agents since pain under the tourniquet is the main reason for discontinuing the procedure. Opiates have not been found to be helpful when added to the lidocaine but may be given at a distant site (such as via the IV infusion in the opposite arm) for general pain control.

Dunbar and Mazze showed that patients with IVRA actually had significantly lower plasma lidocaine concentrations than did those with an axillary block or lumbar epidural anesthesia for similar procedures.8 Peak plasma concentrations are reached 2 to 3 minutes after deflation of the tourniquet, and side effects are minimal if the deflation is cycled after the surgical procedure. The plasma half-life of lidocaine is approximately 60 seconds (see the excellent detailed discussion of pharmacokinetics by Covino21), but the drug demonstrates a theoretical three-compartment model similar to a direct IV infusion once the tourniquet is released.22 Peak blood levels are related to the duration of vascular occlusion and to the concentration of the anesthetic.21,22

Peak plasma lidocaine levels after release of the tourniquet decrease as the time of vascular occlusion (tourniquet time) increases. If the tourniquet is inflated for at least 30 minutes and the deflation-reinflation technique is used when the procedure is finished, the plasma concentration of lidocaine should be approximately 2 to 4 µg/mL, below the 5- to 10-µg/mL level at which dose-related lidocaine reactions occur.8 Tucker and Boas demonstrated a peak plasma lidocaine level of 10.3 µg/mL after a 10-minute period of vascular occlusion,22 as opposed to 2.3 µg/mL if the tourniquet was inflated for 45 minutes.

More dilute solutions of lidocaine are associated with lower peak lidocaine levels. When equal doses of lidocaine are used, peak arterial plasma levels are 40% lower if the 0.5% solution is used than if the 1% solution is used.22 For example, after 10 minutes of vascular occlusion, the peak plasma concentration of lidocaine has been demonstrated to reach 10.3 µg/mL with the 1% solution versus only 5.6 µg/mL when the drug was given under similar circumstances at a 0.5% concentration.22

Site of Injection

Anesthesia is usually achieved no matter where the local anesthetic is injected, but some evidence indicates that the procedure is more successful when the anesthetic is injected distally. Sorbie and Chacho noted the following failure rates associated with specific sites of anesthetic injection23: antecubital fossa, 23%; middle of the forearm or leg, 18%; and hand, wrist, or foot, 4%. In most cases a vein in the dorsum of the hand or foot is used. If local pathology precludes use of the hand, the midforearm or antecubital fossa of the elbow is an acceptable, albeit less desirable alternative as long as the infusion catheter is well below the tourniquet to avoid systemic injection.

Complications

Anesthetic Agent

Serious complications seldom occur if proper attention is paid to technique. True lidocaine allergy is very rare. Other reactions to lidocaine are rare and are usually systemic reactions from high blood levels.8,18,24 High levels may result from miscalculation of dosages, from too rapid release of the tourniquet before the anesthetic has become fixed in tissue (“bolus effect”), or rarely, from advancement of the infusion catheter proximal to the tourniquet, thereby resulting in direct IV infusion.25 To emphasize the safety of this procedure, note that the dose of lidocaine used in the minidose technique is similar to an IV bolus routinely given to patients with significant cardiovascular disease in the presence of ventricular dysrhythmias.

Generally, the central nervous system effects of lidocaine are minor and result in mild reactions such as dizziness, tinnitus, lethargy, headache, or blurred vision. This should not occur in more than 2% to 3% of patients and requires no treatment.8 Transient hypotension and bradycardia may develop but are generally self-limited. Convulsions may occur but are extremely rare.

The most common complication related to the anesthetic agent is rapid systemic vascular infusion, which occurs when a blood pressure cuff explodes or slowly leaks, with consequent loss of anesthesia and high blood levels.26 Similar complications may occur if the cuff is deflated earlier than 20 to 30 minutes after the induction of anesthesia. Both complications are the result of a bolus effect of the anesthetic, similar to an IV injection.

Van Neikerk and Tonkin reported three seizures in a series of 1400 patients.24 Auroy and colleagues reported 23 seizures in 11,229 cases,27 with no cardiac arrest or fatalities, and deemed IVRA safer than general anesthesia or peripheral nerve blocks. Seizures are generally not recurrent and are treated with oxygen and anticonvulsant drugs. Transient cardiovascular reactions, such as bradycardia and hypotension, are possible with large doses of lidocaine. Vasovagal reactions do occur. If resuscitation equipment is available and a precautionary IV line is started in the opposite arm, there should not be any serious sequelae.

One case of cardiac arrest 15 seconds after the use of 200 mg lidocaine has been reported, but the actual clinical scenario may have been a vasovagal reaction rather than a true cardiac arrest.28

Additional Complications

Thrombophlebitis can occur following the IV administration of anesthetics, and the formation of insignificant amounts of methemoglobin with the use of prilocaine hydrochloride (Citanest) has been reported.29 Methemoglobinemia can also theoretically occur with lidocaine but has not been reported. Bupivacaine offers no benefit over lidocaine, has been associated with deaths, and should be avoided.30

An excellent summary of a very favorable experience with IVRA of both the arm and leg in 1900 outpatients is available.31

References

1. Bell, HM, Slater, EM, Harris, WH. Regional anesthesia with intravenous lidocaine. JAMA. 1963;186:544.

2. Holmes, CM. Intravenous regional analgesia: a useful method of producing anesthesia of the limbs. Lancet. 1963;1:245.

3. Bou-Merhi, JS, Gagnon, AR, St Laurent, JY, et al. Intravenous regional anesthesia administered by the operating plastic surgeon: is it safe and effective? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120:1591–1597.

4. Bier, A. Ueber einen neuen weg Localanasthesia an den Gliedmassen zu Erzeugen. Arch Klin Chir. 1908;86:1007.

5. Colbern, EC. Bier block. Anesth Analg. 1970;49:935.

6. Atkinson, PI, Modell, J, Moya, F. Intravenous regional anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 1965;45:313.

7. Colbern, EC. Intravenous regional anesthesia: the perfusion block. Anesth Analg. 1966;45:69.

8. Dunbar, RW, Mazze, RI. Intravenous regional anesthesia: experience with 779 cases. Anesth Analg. 1967;46:806.

9. Roberts, JR. Intravenous regional anesthesia—“Bier block.”. Am Fam Physician. 1978;17:123.

10. Farrell, RG, Swanson, SL, Walter, JR. Safe and effective IV regional anesthesia for use in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1985;14:288.

11. Ogden, PN. Failure of intravenous regional analgesia using a double cuff tourniquet. Anaesthesia. 1984;39:456.

12. Estebe, JP, Naoures, AL, Chemaly, L, et al. Tourniquet pain in a volunteer study: effect of changes in cuff width and pressure. Anaesthesia. 2000;55:21.

13. Raj, PP. Site of action of intravenous regional anesthesia. Reg Anesth. 1979;4:8.

14. Raj, PP, Garcia, CE, Burleson, JW, et al. The site of action of intravenous regional anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 1972;51:776.

15. Evans, CJ, Dewar, JA, Boyes, RN, et al. Residual nerve block following intravenous regional anesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 1974;46:668.

16. Katz, J. Choice of agents for intravenous regional anesthesia. Reg Anesth. 1979;4:10.

17. Albright, GA. Cardiac arrest following regional anesthesia with lidocaine or bupivacaine. Anesthesiology. 1979;51:285.

18. Rosenberg, PH, Kalso, EA, Tuominen, MK, et al. Acute bupivacaine toxicity as a result of venous leakage under the tourniquet cuff during a Bier block. Anesthesiology. 1983;58:95.

19. Reuben, SS, Steinberg, RB, Klatt, JL, et al. Intravenous regional anesthesia using lidocaine and clonidine. Anesthesiology. 1999;91:654.

20. Reuben, SS, Steinberg, RB, Kreitzer, JM, et al. Intravenous regional anesthesia using lidocaine and ketorolac. Anesth Analg. 1995;81:110.

21. Covino, BG. Pharmacokinetics of intravenous regional anesthesia. Reg Anesth. 1979;4:5.

22. Tucker, GT, Boas, RA. Pharmacokinetic aspects of intravenous regional anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 1971;34:538.

23. Sorbie, C, Chacho, PB. Regional anesthesia by the intravenous route. Br Med J. 1965;1:957.

24. Van Niekerk, JP, Tonkin, PA. Intravenous regional analgesia. S Afr Med J. 1966;40:165.

25. Clinical Anesthesia Conference. N Y State J Med. 1966;66:1344.

26. Roberts, JR. Intravenous regional anesthesia. JACEP. 1977;6:261.

27. Auroy, Y, Narchi, P, Messiah, A, et al. Serious complications related to regional anesthesia: results of a prospective survey in France. Anesthesiology. 1997;87:479.

28. Kennedy, BR, Duthie, AM, Parbrook, GD, et al. Intravenous regional anesthesia: an appraisal. Br Med J. 1965;5440:954.

29. Mazze, RI. Methemoglobin concentrations following intravenous regional anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 1968;47:122.

30. Health, ML. Deaths after intravenous regional anesthesia. Br Med J. 1982;285:913.

31. Brown, EM, McGriff, JT, Malinowski, RW. Intravenous regional anesthesia (Bier block). A review of 20 years’ experience. Can J Anaesth. 1989;36:307.