Intraoperative patient positioning

Commonly used positions

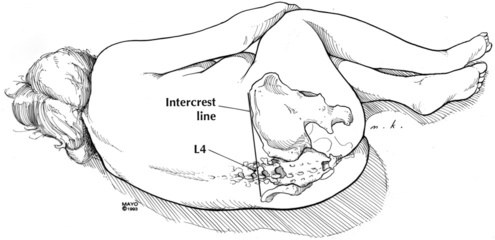

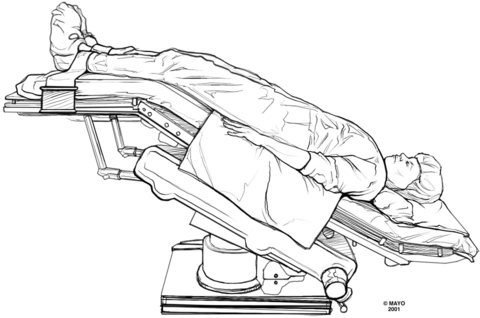

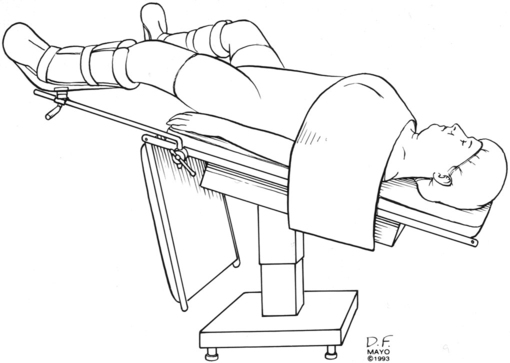

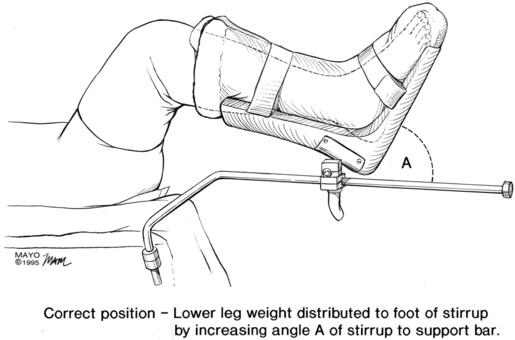

The basic patient positions for surgery are supine, prone, and lateral, with the head down (Trendelenburg position) (Figure 243-1) or head up (reverse Trendelenburg). Most other positions are variations on these basic ones. Lithotomy (supine) with the legs elevated and flexed (Figure 243-2), jackknife (prone and flexed), lateral decubitus (Figure 243-3), beach chair, and sitting are commonly used positioning terms.

Complications resulting from incorrect positioning

Problems related to the trendelenburg position

A steep Trendelenburg position is increasingly being used for laparoscopic procedures, especially for urologic and gynecologic procedures, and can cause occasional difficulties (Figure 243-4). Venous engorgement of the face can be impressive, sometimes resulting in marked conjunctival edema. Airway edema can also result, although this is rarely a problem that delays extubation.

Problems related to the sitting position

The sitting position also has associated risks but also many unique benefits. The primary risks are of venous air embolism (Chapter 137) and cerebral ischemia. When intraarterial cannulas are placed to measure blood pressure when the patient is in the sitting position, placing the transducer at the level of the external auditory meatus is considered the gold standard by many to measure cerebral perfusion pressure.

Problems related to head positioning

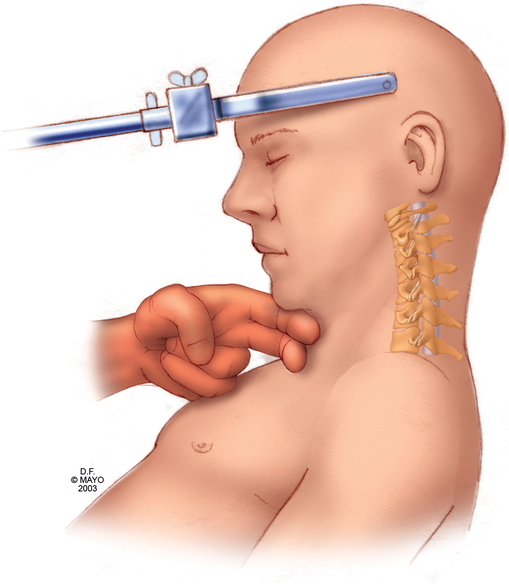

For many operations involving the cranial nerve or ear, nose, or throat, the patient’s head is turned to the side to some degree. Degenerative disease of the cerebral vertebrae or vascular impingement when the head is turned may limit the degree to which the patient’s head can be turned. Only rarely will such a patient have somatosensory evoked potentials monitored to detect spinal cord compromise. The best way to determine the degree of cervical movement that the patient can tolerate is to place the patient in the desired position while awake and check the range of motion carefully before inducing anesthesia. The head should not be flexed to the point where there is less than 2 fingerbreadths of space between the bone of the chin and the sternal notch; quadriplegia may result (Figure 243-5). Age should be considered when positioning the patient with the head turned, flexed, or extended. The cervical and vascular degeneration that contribute to problems can begin in middle age and are nearly always present by the seventh decade of life.

Some have suggested that prolonged prone cases should be performed with the patient’s head pinned in a headrest to remove the risk of pressure on the eye (Figure 243-6) and to attenuate the possibility of injury. To decrease the risk of blindness in patients in the prone position, some have suggested that, in addition to avoiding pressure on the eyes, a mean arterial pressure of at least 65 mm Hg and a hemoglobin concentration of at least 9 g/dL should be maintained. Other risks in this position include corneal abrasion and injury to the lips, nose, and ears. Flexion of the neck in patients with severe rheumatoid arthritis may sublux the odontoid process, which can narrow the cervical spinal canal.

Correct positioning

Upper extremity positioning

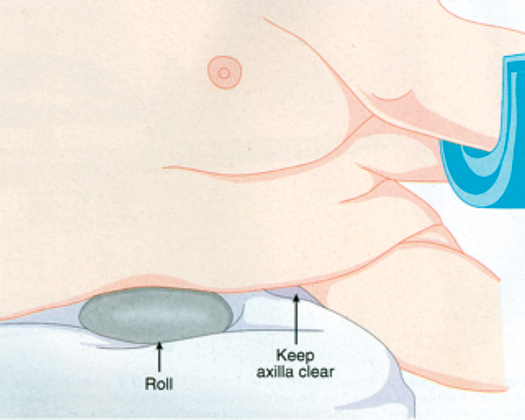

When patients are in the prone position, one or both arms are placed on arm boards in the “surrender” position. In some cases, the arms are tucked beneath the arched frame; in others, both arms are placed at the patient’s sides. Risks to the arms include pressure on or stretching of the brachial plexus and pressure on the ulnar nerve. The brachial plexus can often be palpated at the axilla, and the shoulder can be maneuvered so as to ensure that the plexus is not under tension or pressure. For the lateral position, the use of an axillary roll is important to protect the brachial plexus (Figure 243-7).