Chapter 102 Intradural Extramedullary Spinal Lesions

Before the advent of microsurgical techniques, surgery of many spinal cord neoplasms consisted primarily of open biopsy and radiation therapy.1–3 Recent technologic advances in neurosurgery and diagnostic imaging have expanded the role for operative treatment of spinal tumors. Although Horsely performed the first successful excision of a spinal tumor in 1887, and Elsberg and Frazier advocated resection of spinal tumors in the early part of the 20th century, consistently acceptable morbidity and mortality were not realized until recently.4–7 MRI has facilitated preoperative localization and surgical planning. The use of intraoperative neurologic monitoring and ultrasound has led to reduced operative morbidity. Advances in microsurgical techniques as well as the development of ultrasonic aspiration and laser technology have established microsurgical removal as the most effective treatment for benign intradural extramedullary tumors.

Incidence and Pathology

Tumors of the spine are anatomically classified by their relationship to the dura mater and spinal cord parenchyma. Intradural tumors can be intramedullary or extramedullary, and extramedullary tumors account for approximately three fourths of all intradural spinal tumors.1,5,8,9 Intradural spinal neoplasms make up approximately 10% of primary central nervous system tumors in adults,1,10 and about two thirds are extramedullary, histologically benign, and well circumscribed. Meningioma, schwannoma, and filum terminale ependymoma are the most common histopathologic lesions in the intradural extramedullary space. Meningiomas and nerve sheath neoplasms account for 80% of extramedullary spinal cord tumors, and filum terminale ependymomas make up 15% of these lesions. The remaining 5% includes paragangliomas, drop metastases, and granulomas, all of which are rare.

Meningiomas

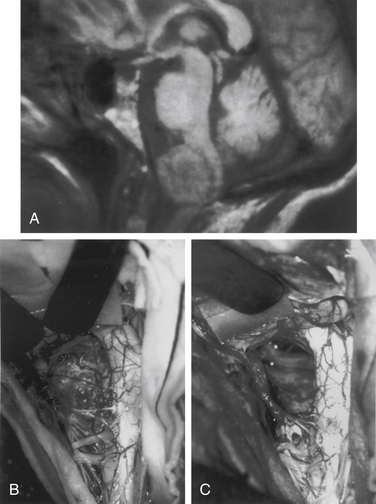

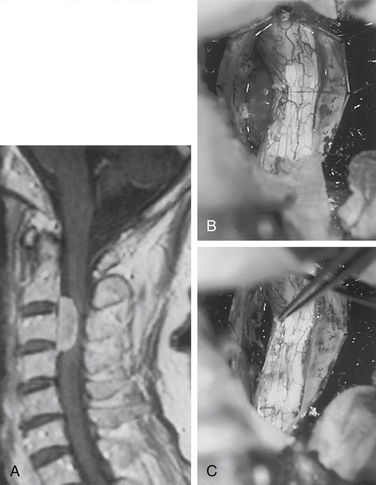

Meningiomas arise from arachnoid cap cells embedded in the dura mater near the nerve root sleeve, reflecting their predominant lateral location and meningeal attachment. Other possible cells of origin include fibroblasts associated with the dura or pia mater, which may account for the occasional ventral or dorsal location of these tumors. Meningiomas occur in all age-groups, but most arise in people between the fifth and seventh decades of life. Women account for 75% to 85% of cases, and about 80% of tumors are thoracic.11–13 The upper cervical spine and foramen magnum are also common sites14 (Fig. 102-1). Here, meningiomas often occupy a ventral or ventrolateral position and may adhere to the vertebral artery near its intradural entry and initial intracranial course. Low cervical and lumbar meningiomas are infrequent. Most spinal meningiomas are entirely intradural; however, about 10% can be both intradural and extradural or entirely extradural.12 Meningiomas are generally solitary, but multiplicity can be observed in patients with neurofibromatosis. The overall incidence of multiplicity in the spine is 1% to 2%.15

Nerve Sheath Tumors: Schwannomas and Neurofibromas

Nerve sheath tumors are categorized as either schwannomas or neurofibromas. Although evidence from tissue culture, electron microscopy, and immunohistochemistry supports a common Schwann cell origin for neurofibromas and schwannomas, the morphologic heterogeneity of neurofibromas suggests participation of additional cell types such as perineural cells and fibroblasts. Neurofibromas and schwannomas merit separate consideration because of distinct demographic, histologic, and biologic characteristics. A schwannoma appears grossly as a smooth, globoid mass that does not produce enlargement of the nerve but is suspended eccentrically from it, sometimes by a discrete attachment. The histologic appearance consists of elongated bipolar cells with fusiform, darkly staining nuclei arranged in compact interlacing fascicles that tend to palisade (Antoni A pattern). A loosely arranged pattern of stellate cells (Antoni B pattern) is less common.10 The histologic appearance of a neurofibroma consists of an abundance of fibrous tissue and the conspicuous presence of nerve fibers within the tumor stroma.16 Grossly, the tumor produces fusiform enlargement of the involved nerve, which makes it impossible to distinguish between them. Multiple neurofibromas establish the diagnosis of neurofibromatosis, but this syndrome should be considered even in patients with solitary involvement.

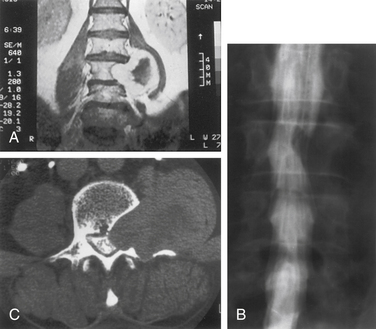

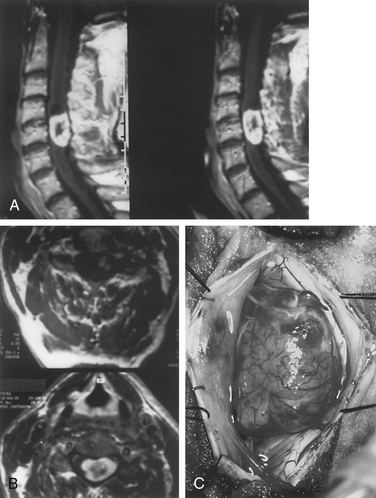

Nerve sheath tumors account for about 25% of intradural spinal cord tumors in adults.12,17 Most are solitary schwannomas occurring throughout the spinal canal. The fourth through sixth decades of life represent the peak incidence of occurrence, and men and women are equally affected. Most nerve sheath tumors arise from a dorsal nerve root. Ventral root tumors are more commonly neurofibromas. Most nerve sheath tumors are entirely intradural, but in 10% to 15% of cases they extend through the dural root sleeve as a dumb-bell–shaped tumor with both intradural and extradural components12 (Fig. 102-2). About 10% of nerve sheath tumors are epidural or paraspinal in location. Intramedullary nerve sheath tumors account for only 1% and are believed to arise from the perivascular nerve sheaths that accompany penetrating spinal cord vessels. Centripetal growth of a nerve sheath tumor can also result in subpial extension, and this occurs most often with plexiform neurofibromas. In these cases, both intramedullary and extramedullary tumor components are apparent. Brachial or lumbar plexus neurofibromas can extend centrally into the intradural space along multiple nerve roots. Conversely, retrograde intraspinal extension of a paraspinal schwannoma usually remains epidural.

About 2.5% of intradural spinal nerve sheath tumors are malignant,18 and at least one half of these occur in patients with neurofibromatosis. Rarely, in children, malignant nerve sheath tumors can be widely disseminated.19 These tumors carry a poor prognosis, and survival is generally less than 1 year. These tumors must be distinguished from the rare cellular schwannoma, which has aggressive histologic features but is associated with a favorable prognosis. Occasionally, malignant melanoma can involve spinal nerve roots and radiographically mimic a neurofibroma.20

Filum Terminale Ependymomas

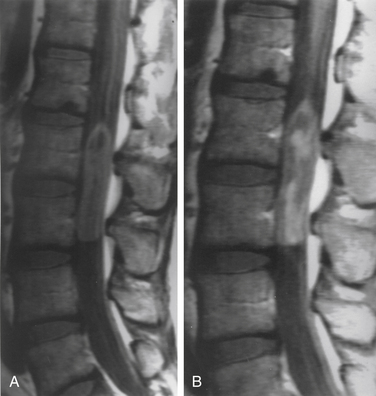

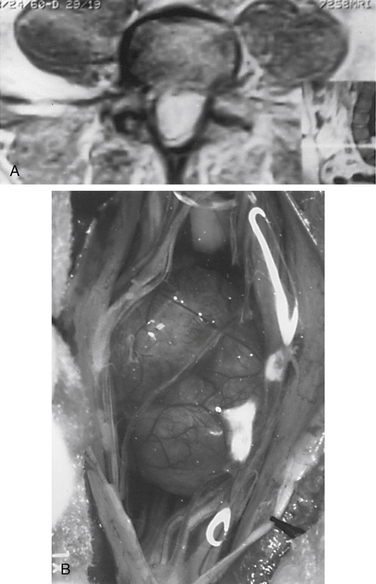

Although filum ependymomas have been classified as intramedullary lesions by virtue of the neuroectodermal derivation of the filum terminale, it is appropriate to consider them with extramedullary tumors from an anatomic and surgical perspective.1,7 About 40% of spinal canal ependymomas arise within the filum terminale1 (Fig. 102-3), most occurring in its proximal intradural portion. Astrocytomas, oligodendrogliomas, and paragangliomas can also originate in the filum but are rare. Filum terminale ependymomas occur throughout life but are most common in the third to fifth decades. Men are slightly more commonly affected. Filum ependymomas and cauda equina nerve sheath tumors occur with about equal frequency in men and women.21,22

Lesions are typically reddish, sausage-shaped growths with moderate vascularity. Although unencapsulated, they are usually well circumscribed and may be covered by arachnoid. They can present with widespread disease, and lesions in the lumbar spine may represent drop metastases from the posterior fossa or other sites. Myxopapillary ependymoma is the most common histologic type encountered. The microscopic appearance consists of a papillary arrangement of cuboidal or columnar tumor cells surrounding a vascularized core of hyalinized and hypocellular connective tissue.10 Nearly all are histologically benign.23 These tumors, however, tend to be more aggressive in people in younger age groups.24

Miscellaneous Pathology

Extramedullary masses can be neoplastic or non-neoplastic. Paragangliomas are rare tumors of neural crest origin arising from the filum terminale or cauda equina.25 They are benign and usually nonfunctioning tumors that histologically resemble extra-adrenal paraganglia. They appear grossly as well-circumscribed vascular tumors and may be clinically and radiographically indistinguishable from filum terminale ependymomas. Identification of dense-core neurosecretory granules on electron microscopy establishes the diagnosis, and complete removal can be accomplished in most cases. Cavernous malformations, hemangioblastomas, and ganglioneuromas may involve an intradural nerve root and appear as extramedullary masses. These lesions can be observed clinically as nerve sheath tumors with early radicular symptoms. Ganglioneuromas may be manifested as dumb-bell–shaped tumors in pediatric patients.

Dermoids, epidermoids, lipomas, teratomas, and neurenteric cysts are inclusion lesions resulting from disordered embryogenesis.26,27 They can occur throughout the spinal canal but are more common in the thoracolumbar and lumbar spine. Intramedullary locations have also been reported. Associated anomalies such as cutaneous lesions, sinus tracts, occult ventral or dorsal rachischisis, and split cord malformations may be present.27,28 Inclusion tumors and cysts are generally seen as masses, but recurrent meningitis, tethered cord syndrome, or congenital deformities may be the predominant clinical finding.

Non-neoplastic lesions may also appear as extramedullary masses, arachnoid cysts being a well-known example. These cysts are most common in the thoracic spine and are usually dorsal to the spinal cord.29 Intraspinal aneurysms are extremely rare. Herniated intervertebral discs have occasionally been reported to rupture through the dura and appear as an intradural extramedullary mass.30

Inflammatory pathologies such as sarcoidosis, tuberculoma, and subdural empyema are rarely seen as intradural mass lesions.30–32 In patients with intrathecal drug delivery systems, especially morphine pumps, intradural granulomas may form around the catheter tip, causing progressive neurologic decline.33

Although spinal carcinomatous meningitis frequently complicates systemic cancer, secondary metastatic mass lesions of the intradural extramedullary compartment are rare. Malignant intracranial neoplasms that oppose the subarachnoid space or ventricles are the most likely intracranial tumors to demonstrate cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) drop metastasis into the spinal subarachnoid space.4 Systemic cancer accesses the subarachnoid space, either through direct dural root sleeve penetration or, more commonly, hematogenously via the choroid plexus.34,35

Clinical Features

Extramedullary spinal cord lesions cause a variety of clinical signs and symptoms, and no particular clinical syndrome is pathognomonic. In general, pain followed by progressive neurologic deficit is the clinical course most often encountered. The classic syndrome historically ascribed to intradural extramedullary tumors consists of progression through segmental, hemicord, and transverse cord dysfunction.36,37 This presentation, however, is rarely observed in current clinical practice and is not specific to extramedullary lesions. Generally, the clinical features of most extramedullary tumors reflect a slow-growing intraspinal mass. Specific manifestations are variable and determined mainly by tumor location. Upper cervical and foramen magnum tumors are often ventral and are frequently accompanied by suboccipital pain, distal arm weakness, and hand intrinsic muscle weakness and atrophy causing clumsiness.14 The etiology of this well-known syndrome is uncertain, but it most likely results from venous insufficiency. Increased intracranial pressure and hydrocephalus can occur rarely with an extramedullary tumor at any level but are more common with upper cervical lesions.38 The mechanism is probably related to elevation of the CSF protein and resulting impaired CSF flow and absorption. Segmental motor weakness and long-tract signs are the hallmarks of low cervical and midcervical tumors. Early signs and symptoms are typically asymmetrical, which reflects the predominantly lateral location of most intradural tumors. Brown-Séquard syndrome, characterized by ipsilateral corticospinal spinal tract and posterior column and contralateral spinothalamic tract dysfunction, is common.

Thoracic tumors frequently produce long-tract signs, and corticospinal tracts are particularly vulnerable. Initial signs of stiffness and early muscle fatigue eventually give way to spasticity. Weakness usually begins distally, particularly with dorsiflexion of the ankle and large toe. Sensory gait ataxia may result from bilateral posterior column compression with dorsal midline tumors. Bowel and bladder functions are not significantly impaired until late in the clinical course. Filum ependymomas are characterized most frequently by back pain and subsequent asymmetrical radiation to both legs. Increased pain on recumbency, an important clinical feature of extramedullary tumors, is most often associated with large cauda equina lesions. Subarachnoid hemorrhage has also been reported as a presenting feature of an extramedullary tumor.39

Imaging Evaluation

Lesion signal abnormalities, CSF capping, and spinal cord or cauda equina displacement identify most extramedullary masses in a technically adequate MRI study.40 The diagnosis of lipoma, neurenteric cysts (dermoid or epidermoid), arachnoid cysts, or vascular pathology can often be established on the basis of imaging characteristics alone. Gadolinium-enhanced images markedly increase the sensitivity of MRI, particularly for small tumors.

Most extramedullary tumors are isointense or slightly hypointense with respect to the spinal cord on T1-weighted images. Nerve sheath tumors are more likely to be hyperintense to the spinal cord than meningiomas on T2-weighted images. Cauda equina tumors usually demonstrate increased signal intensity with respect to CSF on both T1 and T2 pulse sequences. However, small cauda equina tumors are easily overlooked on noncontrast scans.40,41

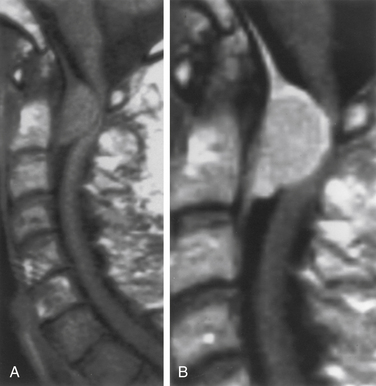

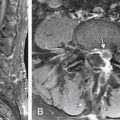

Virtually all extramedullary spinal tumors demonstrate some degree of contrast enhancement. Meningiomas typically exhibit intense uniform enhancement, although nonenhancing calcifications or intratumoral cysts may be seen. Enhancement of the adjacent dura, a “dural tail,” strongly supports the diagnosis of meningioma (Fig. 102-4). Although most nerve sheath tumors and filum ependymomas also demonstrate uniform contrast uptake, heterogeneous enhancement from intratumoral cysts, hemorrhage, or necrosis is frequent (Fig. 102-5).

Currently, myelography and myelo-CT are not often used for the evaluation of intradural pathology. Nevertheless, the spatial resolution of myelo-CT remains superior to that of MRI. For tumors that are closely applied to the surface of the spinal cord and when the MRI is equivocal with respect to an intramedullary or extramedullary location, myelo-CT can sometimes provide better resolution. The intradural or extradural distribution of a paraspinal or dumb-bell–shaped tumor is also better visualized with myelo-CT than with MRI (see Fig. 102-2C).

Management

After clinical and imaging evaluation reveal a lesion that is believed to be a spinal cord tumor, tissue diagnosis is necessary. The surgical objective for most intradural extramedullary spinal cord lesions is gross total removal, and surgical planning must proceed accordingly. Immediately preoperatively, patients are given high-dose glucocorticoids, if spinal cord manipulation is anticipated, and intravenous antibiotics. Mechanical venous thromboembolism prophylaxis and a Foley catheter are used. Most tumors are accessible with the patient in the prone position. For cervical lesions, stabilization of the head and neck in pins is necessary as and aid to microscopic dissection. Adequate exposure is crucial and is dictated by the location and extent of the lesion. Intraoperative monitoring with somatosensory-evoked potentials and motor-evoked potentials should be considered; this monitoring is especially useful with intramedullary extension of tumor. Spontaneous and triggered electromyography can be used to identify nerve roots in filum pathology.42 Such monitoring does not uniformly protect against neural injury, and false-positive alarms are frequent. Surgical decision making must incorporate the patient’s preoperative neurologic status, the likely pathology of the tumor, and technical challenges presented by a particular lesion. Intraoperative ultrasound is often useful in localizing and delineating the extent of the pathology if it is not obvious on inspection. Competent dural closure is essential. Steroids are tapered postoperatively, and early mobilization and rehabilitation are encouraged.

Surgical Considerations

The optimal treatment of intradural extramedullary tumors is surgical excision. For nerve sheath lesions, this can be accomplished in nearly all cases through standard laminectomy.7 Recurrences are rare when gross total removal has been achieved. Most nerve sheath tumors are dorsal or dorsolateral to the spinal cord and are easily seen after opening the dura mater (Fig. 102-6). Ventral tumors may require dentate ligament section to achieve adequate visualization, and lumbar tumors may be covered by the cauda equina or conus medullaris. The nerve roots must be separated to provide adequate visualization.

Laminectomy provides adequate exposure for spinal meningiomas in most cases. Unilateral laminectomy and facetectomy can be used for eccentrically located or ventral tumors. Large ventral tumors can also be approached satisfactorily through standard dorsal exposures because they have already provided the necessary spinal cord retraction. Suture retraction on a divided dentate ligament or on noncritical dorsal nerve roots provides additional ventral exposure. Depression of the paraspinal muscle mass with table-mounted retractors further facilitates ventral access. Alternatively, a costotransversectomy or lateral extracavitary approach can be used for ventral thoracic tumors. The extreme lateral approach is used when there is a significant ventral tumor component above the foramen magnum.43 Resection of ventrally located cervical nerve sheath tumors through a ventral corpectomy approach has also recently been reported.44 Similarly, a thoracoscopic approach to ventral thoracic tumors has also been decribed.45 Both of these techniques have been described via case reports, however, and the reader is cautioned that intradural tumor resection from a ventral approach is technically challenging.

The role of surgery in treating filum terminale ependymomas depends on the size of the tumor and its relationship to the surrounding roots of the cauda equina. Gross total en bloc resection should be attempted whenever possible. This can usually be accomplished for small and moderate-sized tumors that remain well circumscribed within the fibrous coverings of the filum terminale and are easily separated from the cauda equina nerve roots. A portion of uninvolved filum terminale is generally present between the tumor and spinal cord. Amputation of the afferent and efferent filum segments is required for tumor removal. Internal decompression is not used for small and moderate-sized tumors because it can increase the risk of CSF dissemination. Recurrences after successful en bloc resection are rare.

Adjuvant Therapy

The effects of postoperative radiation therapy on spinal meningiomas and nerve sheath tumors have not been extensively studied. Radiation treatment can be considered for subtotally resected lesions that are recurrent and histologically and clinically aggressive. It is probably best to wait until reoperation is complete before instituting therapy. In one series, 3.5% of patients receiving radiation therapy experienced neurologic worsening attributable to the therapy.46

Biologically aggressive filum ependymomas, which are more common in the younger population, demonstrate early tumor recurrence and can be treated with radiation therapy. If significant tumor burden is present after initial surgery, however, as in the case of known CSF dissemination, postoperative radiation therapy is given as a primary adjunct. Postoperative radiation therapy is delayed in situations where piecemeal total or near total removal has been accomplished. In these cases, tumor recurrences can be treated with repeat surgery and followed by radiation therapy. Although the response of spinal cord ependymomas to radiation therapy is unpredictable, there is some evidence that long-term control can be achieved with radiation therapy in some patients.47 This response cannot be predicted individually. Because prior radiation therapy markedly increases the morbidity of future surgical prospects, it is generally delayed in situations where further surgery may be contemplated. The role of stereotactic radiosurgery in the management of inoperable or recurrent tumors is currently being evaluated as well and may be useful in reducing surgical morbidity of tumors adherent to the spinal cord.48,49

Recently, a phase III study was conducted looking at the use of etoposide as salvage chemotherapy in patients with recurrent spinal cord ependymomas. Ten patients were treated, and five achieved stable disease status. However, most of these patients had intramedullary tumors, so these results may not be relevant to the more benign tumors of the cauda equina.50

Operative Technique

Meningiomas

A variety of strategies can be used for removal of spinal meningiomas. Dorsal and dorsolateral lesions are delivered away from the spinal cord with traction on the open dural margins, and circumscribing excision of the dural origin completes the removal. For lateral and ventral tumors, the arachnoid over the exposed portion of the tumor is incised and reflected so that the dissection can proceed directly on the tumor surface (Fig. 102-7). The rostral and caudal tumor poles should be identified. Small cotton pledgets can be placed in the spinal lateral canal gutters on either side of the tumor to minimize blood spillage into the subarachnoid space. The exposed tumor surface is then cauterized to diminish tumor vascularity and to shrink tumor mass. Large tumors are bisected and debulked through a central trough. The tumor segment apposing the spinal cord is then delivered into the resection cavity with gentle traction and surface dissection. The remaining dura-based tumor is amputated from the dural attachment, and the attachment is then extensively coagulated. Alternatively, the dural base can be excised and replaced with a thoracodorsal fascia patch graft. All blood and debris are irrigated from the subarachnoid space with warm saline, and arachnoid adhesions holding the cord in a deformed position are divided. These maneuvers can diminish the risk of postoperative complications such as spinal cord tethering, arachnoiditis, delayed syrinx formation, and hydrocephalus, which occasionally complicate extramedullary tumor removal. Rarely, a spinal meningioma extends through a dural nerve root sleeve and appears as a dumb-bell–shaped tumor. The techniques for removal are similar to those described here for nerve sheath tumors.

Nerve Sheath Tumors

Surgical exposure of nerve sheath tumors depends on the specific anatomy of the lesion. Tumors that are small and strictly intradural can be approached via dorsal laminectomy. Ventrally located tumors may require facetectomy, transthoracic, or far lateral approaches. Once exposure is achieved, a plane of dissection directly on the tumor surface must be identified.

There is usually an arachnoid membrane tightly applied to the tumor surface (see Fig 102-5C). This is the fenestrated arachnoid layer that separately ensheaths each dorsal and ventral nerve root within the subarachnoid space.51 This layer is sharply incised and reflected off the tumor surface. The tumor capsule is cauterized to diminish vascularity and shrink tumor volume. Tumor removal requires identification and division of the proximal and distal nerve root tumor attachments, which may not be immediately apparent with large tumors. Internal decompression with a laser or ultrasonic aspirator is used in such cases. Sacrifice of the nerve rootlets of origin is usually required for tumor removal. Occasionally, some fascicles of the nerve rootlet can be preserved, especially for smaller tumors. It is usually possible, however, to preserve the corresponding intradural nerve root because the fenestrated arachnoid sheaths allow anatomic separation of the dorsal and ventral nerve roots to a point just distal to the dorsal root ganglion. In a typical case involving dorsal root tumor origin, for example, it is possible to preserve the ventral root, which is tightly applied to the ventral tumor surface. Extension of a dumb-bell–shaped tumor through the root sleeve, however, usually necessitates resection of the entire spinal nerve.51 This rarely causes significant nerve deficit, even at the cervical and lumbar enlargements. The function of the involved root has probably already been compensated for by adjacent roots. A very proximal tumor origin may be partially embedded in the epipial tissue or may elevate the pia to occupy a subpial location. The tumor-cord junction may be difficult to develop in these cases and requires resection of a segment of pia to effect complete removal.

Outcome

The results of surgery for intradural extramedullary spinal cord tumors are usually excellent. Neurologic morbidity is typically less than 15%, and mortality is extremely uncommon.7,52 Complications are generally related to wound healing and CSF leakage. Most patients have not received radiation therapy; therefore, conservative treatment with lumbar drainage is sufficient management for CSF leakage in most cases. Neurologic complications, such as new deficits or exacerbation of existing ones, are uncommon but are most often associated with manipulation of the cauda equina. Motor and sensory deficits typically improve after surgery, but return of bladder function is variable. Improvement in preoperative deficits is typical and may be dramatic early in the postoperative period. Recovery is related to the duration and severity of the existing deficit and the age of the patient.

Meningiomas

Recurrence of spinal meningiomas after total resection is about 1% at 5 years and 6% at 14 years. Subtotally resected lesions have average recurrence rates of approximately 15%.11,13 Dural resection versus coagulation apparently does not significantly affect recurrence.13 Meningiomas with extradural spread or en plaque lesions are more difficult to remove and tend to recur more frequently. These lesions are also associated with greater degrees of postoperative morbidity. These factors must be balanced when planning the extent of resection.

Nerve Sheath Tumors

Total removal of neurofibromas and schwannomas not associated with neurofibromatosis is generally curative.7,53 However, tumors with extensive paraspinal involvement that are subtotally resected have a definite propensity to recur. Deficits resulting from sacrifice of the involved nerve roots are usually minor and well tolerated. Patients with multiple lesions from neurofibromatosis should usually be observed. Resection is reserved for progressive and symptomatic focal lesions.

Filum Ependymomas

Neurologic deterioration after removal of filum ependymomas is more frequent than that associated with nerve sheath tumors and meningiomas.23,40,54 Lesions involving the conus medullaris or intimately adherent to many roots of the cauda equina carry the highest risk of postoperative morbidity. Recurrence after gross total resection is rare, and subtotally removed lesions recur in approximately 20% of cases. Survival after total removal is almost 100%.7,23 Incompletely resected lesions treated with postoperative radiation therapy are associated with 5- and 10-year survival rates of 69% and 62%, respectively.47,55 Subtotally removed lesions should be frequently followed by MRI.

Summary

Treatment of intradural extramedullary spinal cord lesions remains a gratifying area of neurosurgery. Advances in imaging sensitivity and refinement of microsurgical skills have allowed removal alone to be viewed as definitive treatment in most cases. Early diagnosis and aggressive definitive treatment, when possible, optimize the management of most of these neoplasms.

Kernohan J.W., Sayre G.P. Tumors of the central nervous system, fascicle 35. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1952.

McCormick P.C. Anatomic principles of intradural surgery. Clin Neurosurg. 1994;41:204-223.

McCormick P.C., Post K.D., Stein B.M. Intradural extramedullary tumors in adults. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 1990;1:591-608.

Nittner K. Spinal meningiomas, neurinomas and neurofibromas, and hourglass tumours. In: Vinken P.H., Bruyn G.W., editors. Handbook of clinical neurology. New York: Elsevier; 1976:177-322.

Sloof J.L., Kernohan J.W., MacCarthy C.S. Primary intramedullary tumors of the spinal cord and filum terminale. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1964.

Solero C.L., Fornari M., Giombini S. Spinal meningiomas: review of 174 operated cases. Neurosurgery. 1989;25:153-160.

Sonneland P.R.W., Scheithauer B.W., Onofrio B.M. Myxopapillary ependymoma: a clinicopathologic and immunocytochemical study of 77 cases. Cancer. 1985;56:883-893.

St Amour T.E., Hodges S.C., Ross J.S., et al. MRI of the spine. New York: Raven Press; 1994. pp 299–434

1. Sloof J.L., Kernohan J.W., MacCarthy C.S. Primary intramedullary tumors of the spinal cord and filum terminale. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1964.

2. Woltman H.W., Kernohan J.W., Adson A.W., et al. Intramedullary tumors of the spinal cord and gliomas of intradural portion of filum terminale: fate of patients who have these tumors. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1951;65:378-393.

3. Wood E.H., Berne A.S., Taveras J.M. The value of radiation therapy in the management of intrinsic tumors of the spinal cord. Radiology. 1954;63:11-24.

4. Calvo F.A., Hornedo J., De La Terra A. Intracranial tumors with risk of dissemination in neuroaxis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1983;9:1297-1301.

5. Elsberg C.A. Surgical disease of the spinal cord, membranes, and nerve roots. New York: PB Heuber; 1941.

6. Gowers W., Horsley V. A case of tumor of the spinal cord. Removal. Recovery. Med Chir Trans. 1888;71:377-428.

7. McCormick P.C., Post K.D., Stein B.M. Intradural extramedullary tumors in adults. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 1990;1:591-608.

8. Guidetti B., Fortuna A. Differential diagnosis of intramedullary and extramedullary tumours. In: Vinken P.J., Bruyn G.W., editors. Handbook of clinical neurology. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1975:51-75.

9. Guidetti B., Mercuri S., Vagnozzi R. Long-term results of the surgical treatment of 129 intramedullary spinal gliomas. J Neurosurg. 1981;54:323-330.

10. Kernohan J.W., Sayre G.P. Tumors of the central nervous system, fascicle 35. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1952.

11. Levy W.J., Bay J., Dohn D.F. Spinal cord meningioma. J Neurosurg. 1982;57:804-812.

12. Nittner K. Spinal meningiomas, neurinomas and neurofibromas, and hourglass tumours. In: Vinken P.H., Bruyn G.W., editors. Handbook of clinical neurology. New York: Elsevier; 1976:177-322.

13. Solero C.L., Fornari M., Giombini S. Spinal meningiomas: review of 174 operated cases. Neurosurgery. 1989;25:153-160.

14. Stein B.M., Leeds N.E., Taveras J.M. Meningiomas of the foramen magnum. J Neurosurg. 1963;20:740-751.

15. Okazaki H. Fundamentals of neuropathology. New York: Igaku-Shoin; 1983.

16. Russel D.S., Rubinstein L.J. Pathology of tumors of the central nervous system. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1989. pp 192–214

17. Levy W.J., Latchaw J., Hahn J.F. Spinal neurofibromas: a report of 66 cases and a comparison with meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 1986;18:331-334.

18. Seppala M.T., Haltia M.J.J. Spinal malignant nerve sheath tumor or cellular schwannoma? A striking difference in prognosis. J Neurosurg. 1993;79:528-532.

19. Chamoun R.B., Whitehead W.E., Dauser R.C., et al. Primary disseminated intradural malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor of the spine in a child: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2009;45(3):230-236.

20. Kanatas A.N., Bullock M.D., Pal D., et al. Intradural extramedullary primary malignant melanoma radiographically mimicking a neurofibroma. Br J Neurosurg. 2007;21:39-40.

21. Fearnside M.R., Adams C.B.T. Tumours of the cauda equina. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1978;41:24-31.

22. Norstrom C.W., Kernohan J.W., Love G. One hundred primary caudal tumors. JAMA. 1961;178:1071-1077.

23. Sonneland P.R.W., Scheithauer B.W., Onofrio B.M. Myxopapillary ependymoma: a clinicopathologic and immunocytochemical study of 77 cases. Cancer. 1985;56:883-893.

24. Davis C., Barnard R.O. Malignant behavior of myxopapillary ependymoma. J Neurosurg. 1985;62:925-929.

25. Reyes M.G., Torres H. Intrathecal paraganglioma of the cauda equina. Neurosurgery. 1984;15:578-582.

26. Agnoli A.L., Laun A., Schonmayr R. Enterogenous intraspinal cysts. J Neurosurg. 1984;61:834-840.

27. Pang D. Split cord malformation. Part II: clinical syndrome. Neurosurgery. 1992;31:481-500.

28. Gregorios J.B., Gree B., Page L. Spinal cord tumors presenting with neural tube defects. Neurosurgery. 1986;19:962-966.

29. Nabors M.W., Pait T.G., Byrd E.B. Updated assessment and current classification of spinal meningeal cysts. J Neurosurg. 1988;68:366-377.

30. McCormick P.C., Stein B.M. Miscellaneous intradural pathology. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 1990;1:687-700.

31. Fraser R.A.R., Ratzan K., Wolpert S.M. Spinal subdural empyema. Arch Neurol. 1973;28:235-238.

32. Holtzman R.N., Hughes J.E., Sachdev R.K., Jarenwattananon A. Intramedullary cysticercosis. Surg Neurol. 1986;26:187-191.

33. Miele V.J., Price K.O., Bloomfield S., et al. A review of intrathecal morphine therapy related granulomas. Eur J Pain. 2006;10(3):251-261.

34. Olson M.E., Chernick N.L., Posner J.B. Infiltration of the leptomeninges by systemic cancer. Arch Neurol. 1974;30:122-137.

35. Perrin R.G., Livingston K.E., Asrabi B. Intradural extramedullary metastasis. J Neurosurg. 1982;56:835-837.

36. Elsberg C.A. Tumors of the spinal cord and the symptoms of irritation and compression of the spinal cord and nerve roots: pathology, symptomatology, diagnosis, and treatment. New York: PB Heuber; 1925.

37. Frazier C.H. Surgery of the spine and spinal cord. New York: Appleton; 1919.

38. Feldman E., Bromfield E., Navia B. Hydrocephalic dementia and spinal cord tumor. Arch Neurol. 1986;43:714-718.

39. Divitiis E.D., Maiuri F., Corriero G. Subarachnoid hemorrhage due to a spinal neurinoma. Surg Neurol. 1985;24:187-190.

40. St Amour T.E., Hodges S.C., Ross J.S., et al. MRI of the spine. New York: Raven Press; 1994. pp 299–434

41. Epstein N.E., Bhuchar S., Gavin R. Failure to diagnose conus ependymomas by magnetic resonance imaging. Spine. 1989;14:134-137.

42. Malhorta N.R., Shaffrey C.I. Intraoperative electrophysiological monitoring in spine surgery. Spine. 2010;35:2167-2179.

43. Sen C.N., Sekhar L.N. An extreme lateral approach to intradural lesions of the cervical spine and foramen magnum. Neurosurgery. 1990;27:197-204.

44. O’Toole J.E., McCormick P.C. Midline ventral intradural schwannoma of the cervical spinal cord resected via anterior corpectomy with reconstruction: technical case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:1482-1485.

45. Dickman C.A., Apfelbaum R.I. Thoracoscopic microsurgical resection of thoracic schwannoma: a case report. J Neurosurg. 1998;88:898-902.

46. Engelhard H.H., Vilano J.L., Porter K.R., et al. Clinical presentation, histology, and treatment in 430 patients with primary tumors of the spinal cord, spinal meninges, or cauda equina. J Neurosurg Spine. 2010;13:67-77.

47. Whitaker S.J., Bessel E.M., Ashley S.E. Post-operative radiotherapy in the management of spinal cord ependymoma. J Neurosurg. 1991;74:720-728.

48. Murphy M.J., Adler J.R.Jr., Bodduluri M., et al. Image guided surgery for the spine and pancreas. Comput Aided Surg. 2000;5:278-288.

49. Sahgal A., Bilsky M., Chang E.L., et al. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for spinal metastases: current status, with a focus on its application in the postoperative patient. J Neurosurg Spine. 2011;14:151-166.

50. Chamberlain M.C. Salvage chemotherapy for recurrent spinal cord ependymoma. Cancer. 2002;95:997-1002.

51. McCormick P.C. Anatomic principles of intradural surgery. Clin Neurosurg. 1994;41:204-223.

52. Epstein F.J., Farmer J.P. Pediatric spinal cord tumor surgery. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 1990;1:569-590.

53. Schwade J.G., Wara W.M., Sheline G.E. Management of primary spinal cord tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1978;4:389-393.

54. McCormick P.C., Torres R., Post K.D. Intramedullary ependymoma of the spinal cord. J Neurosurg. 1990;72:523-533.

55. Garrett P.G., Simpson W.J.K. Ependymomas: results of radiation treatment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1983;9:1121-1124.