102 Intracranial and Other Central Nervous System Lesions

• A comprehensive patient history is imperative to narrow the differential diagnosis when a new mass lesion is discovered on radiographic imaging.

• A complaint of dizziness requires cerebellar testing, including finger-nose, heel-shin, dysdiadochokinesia, and gait evaluation.

• Fever in the setting of a neurologic complaint requires both a neurologic examination and consideration of neuroimaging.

• Any patient with a first-time seizure warrants a non–contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the head regardless of age (Box 102.1).

• CT scans reliably demonstrate lesions 1.0 cm or larger.

• Magnetic resonance imaging should be performed if there is significant concern for a central nervous system lesion in patients with negat ive CT findings.

Box 102.1

Indications for Computed Tomography of the Brain in Patients with First-Time Seizures

Adapted from guidelines developed by the U.S. Headache Consortium, American College of Emergency Physicians, and the American College of Radiology. American College of Emergency Physicians. Clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation and management of patients presenting to the emergency department with acute headache. Ann Emerg Med 2002;39:108.

Epidemiology

Patients with intracranial lesions typically have headaches, seizures, focal neurologic changes, weakness, fatigue, or any combination of these findings. Headaches occur in approximately 50% of patients with central nervous system (CNS) tumors; however, brain tumors are uncommon in patients with a headache and normal findings on neurologic examination (<1% of the time).1 Thus emergency physicians should always consider the presence of a brain tumor in the differential diagnosis but should use neuroimaging judiciously (Table 102.1).2,3 Focal neurologic changes always warrant further investigation, including laboratory tests, radiographic imaging, and neurologic or neurosurgical consultation (or both).

Table 102.1 Guidelines for Neuroimaging in Patients with a Headache

| CLINICAL FINDING | RECOMMENDATION |

|---|---|

| “Thunderclap” headache with abnormal neurologic findings | Emergency neuroimaging recommended |

| Signs of increased intracranial pressure; fever and nuchal rigidity | Safe performance of lumbar puncture recommended |

| “Thunderclap” headache | Neuroimaging should be considered |

| Headache radiating to the neck | |

| Temporal headache in an older individual | |

| New-onset headache in a patient who: | |

| Is HIV positive | |

| Has a previous diagnosis of cancer | |

| Is in a population at high risk for intracranial disease | |

| Accompanied by an abnormal neurologic findings, including but not limited to papilledema, unilateral loss of sensation, weakness, and hyperreflexia | |

| Migraine and normal neurologic findings | Neuroimaging not usually warranted |

| Headache worsened by the Valsalva maneuver, wakes the patient from sleep, or is progressively worsening | No recommendation (some data revealing increased risk for intracranial abnormality, not sufficient for recommendation) |

| Tension headache with normal neurologic findings | No recommendation (insufficient data) |

Adapted from guidelines developed by the U.S. Headache Consortium, American College of Emergency Physicians, and American College of Radiology. American College of Emergency Physicians. Clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation and management of patients presenting to the emergency department with acute headache. Ann Emerg Med 2002;39:108.

Pathophysiology

Autopsy diagnosis reveals that nearly 25% of patients who die of cancer had intracranial metastasis (Fig. 102.1). The lung is the most common origin of brain metastases. Breast cancer (especially ductal carcinoma) has a propensity to metastasize to the cerebellum and the posterior pituitary gland; however, breast cancer that metastasizes to bone tends to not metastasize to the brain.

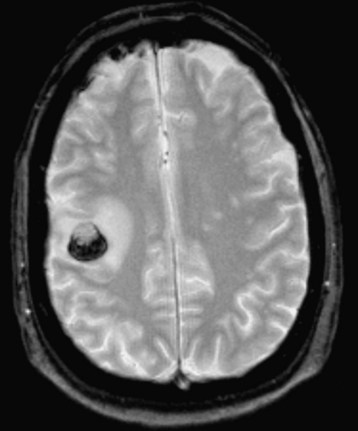

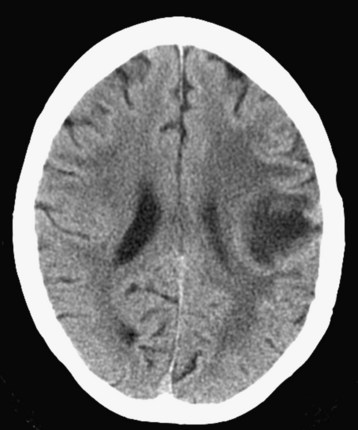

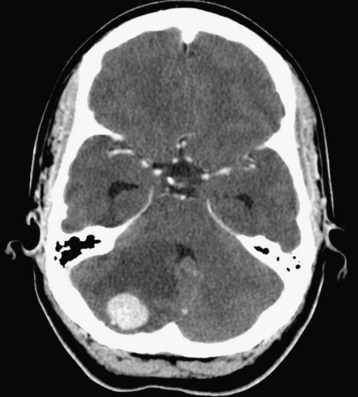

Although metastatic disease is a common form of intracranial mass lesion, other mass lesion considerations include lymphoma (Fig. 102.2), glioblastoma multiforme (Fig. 102.3), astrocytoma, ependymoma, meningioma, oligodendroglioma, medulloblastoma, hemangioblastoma, neurocysticercosis, toxoplasmosis, tuberculoma, tuberous sclerosis, and arteriovenous malformations.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

The initial diagnostic modality in a patient with a new neurologic complaint is a non–contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan. Most brain tumors causing clinical symptoms are visible on CT scans, and all are visible with the various contrast-enhanced techniques of CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). On nonenhanced CT, brain tumors are visualized by mass effect and altered attenuation. Masses may be hypodense, isodense, or hyperdense with respect to surrounding structures and can be associated with vasogenic edema, which is visualized by low attenuation of the white matter (Box 102.2). Extraaxial lesions can best be appreciated with bone window settings because bone erosion or hyperostosis may be present.

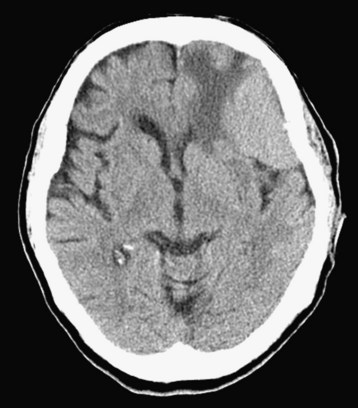

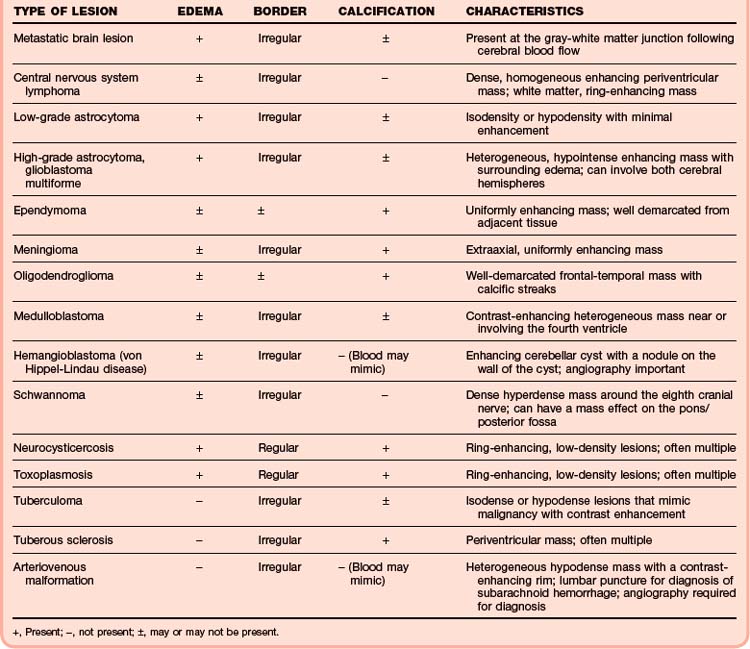

Calcification can be useful in isolating brain tumors. Oligodendrogliomas contain calcification in 90% of cases. Other tumors with calcification include choroid plexus tumors, ependymoma, central neurocytoma, meningioma (Fig. 102.4), craniopharyngioma, teratoma, and chordoma. Nonmalignant lesions such as neurocysticercosis, toxoplasmosis, and tuberous sclerosis exhibit calcific changes on radiographic imaging as well (Table 102.2).

Hemorrhage within a defined lesion on a CT scan should suggest the possibility of an arteriovenous malformation or hemangioblastoma (Fig. 102.5). Contrast-enhanced CT or MRI may identify more than 95% of arteriovenous malformations. Lesions appear as a heterogeneous, hypodense mass with hyperdense regions within the mass; an enhancing rim may also be visible (Fig. 102.6). In patients with negative CT findings but a high index of clinical suspicion, lumbar puncture with cerebrospinal fluid analysis is necessary. If the index of clinical suspicion is high and the diagnosis is suggested by findings on CT, angiography is required to better define the lesion and develop a management strategy. Laboratory analysis of coagulation, including the prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and international normalized ratio, should also be undertaken.

Treatment

Primary and metastatic brain lesions may require a multifaceted approach to medical care. In the emergency department setting, glucocorticoids and prophylactic antiepileptics (phenytoin, fosphenytoin, phenobarbital) may be given before admission. Surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy are options for further long-term treatment plans, but they are usually tailored to the specific tissue diagnosis when it pertains to a solid mass lesion.5

Infectious lesions such as abscesses (Fig. 102.7), neurocysticercosis, toxoplasmosis, and tuberculomas usually require consultation with infectious disease specialists. Serologic examination may prove useful for determining a diagnosis and treatment approach. Antibiotic and antiparasitic medications may be administered under the guidance of these consultants; regimens including clindamycin, albendazole, praziquantel, sulfadiazine, and pyrimethamine may be instituted with or without glucocorticoids.

American College of Emergency Physicians. Clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult patients presenting to the emergency department with seizures. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:605–625.

Cavaliere R, Farace E, Schiff D. Clinical implications of status epilepticus in patients with neoplasms. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:1746.

Engstrom JW. Tumors of the nervous system. In: Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, et al. Harrison’s manual of medicine. 15th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001:842–844.

Evans RW. Diagnostic testing for the evaluation of headaches. Neurol Clin. 1996;14:1–26.

Schaefer PW, Miller JC, Singhal AB, et al. Headache: when is neuroimaging indicated? J Am Coll Radiol. 2007;4:566–569.

1 Evans RW. Diagnostic testing for the evaluation of headaches. Neurol Clin. 1996;14:1–26.

2 Schaefer PW, Miller JC, Singhal AB, et al. Headache: when is neuroimaging indicated? J Am ColI Radiol. 2007;4:566–569.

3 Clinical policy for the initial approach to patients with a chief complaint of seizure who are not in status epilepticus. American College of Emergency Physicians. Ann Emerg Med. 1993;22:875–883.

4 Engstrom JW. Tumors of the nervous system. In: Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, et al. Harrison’s manual of medicine. 15th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001:842–844.

5 Nieder C, Adam M, Molls M, et al. Therapeutic options for recurrent high-grade glioma in adult patients: recent advances. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2006;60:181–193.