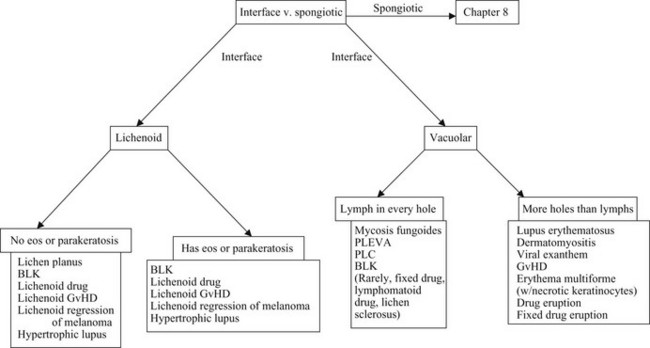

Interface dermatitis

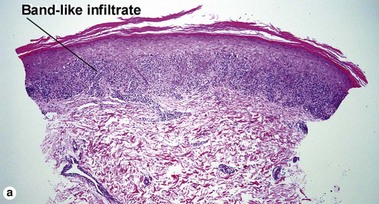

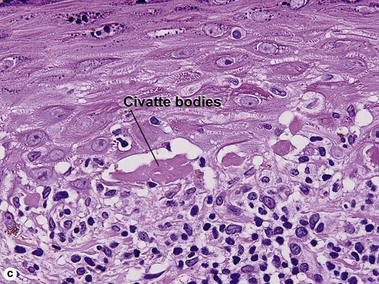

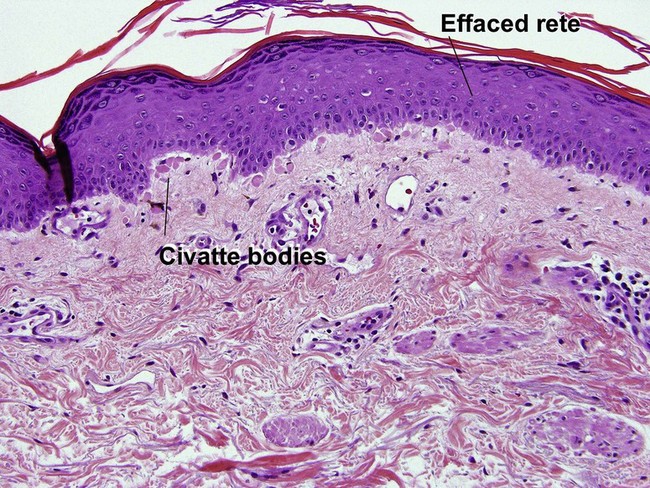

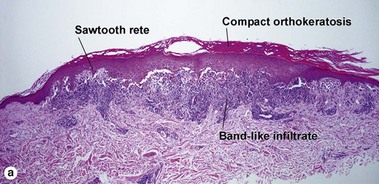

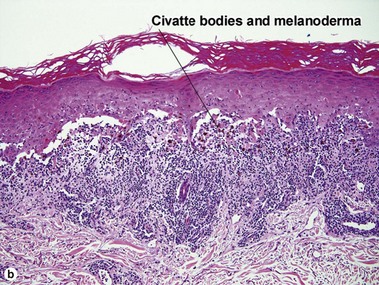

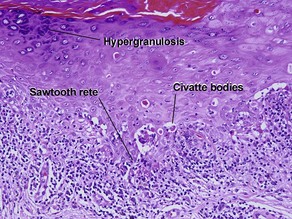

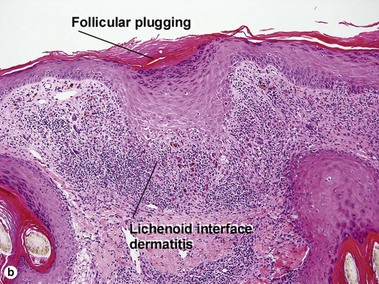

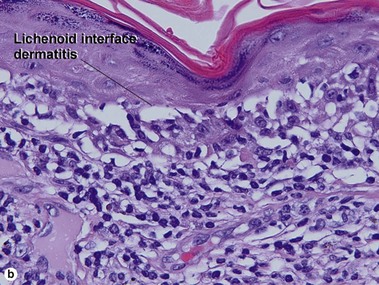

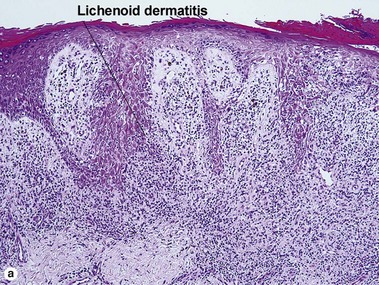

Lichenoid interface dermatitis

Causes of lichenoid interface dermatitis

• Benign lichenoid keratosis (BLK, lichen planus-like keratosis)

• Lichenoid graft-versus-host disease (GvHD)

• Hypertrophic lupus erythematosus

• Lichenoid regression of a melanocytic lesion (usually lentigo maligna)

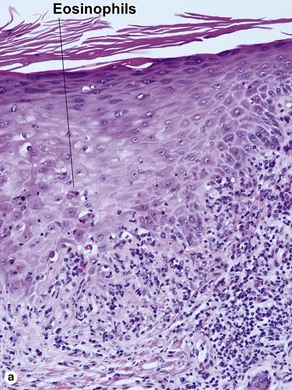

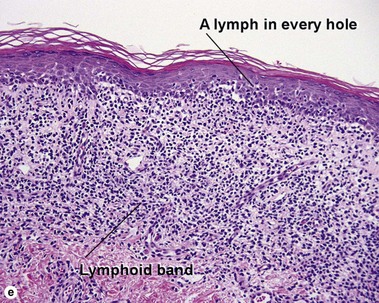

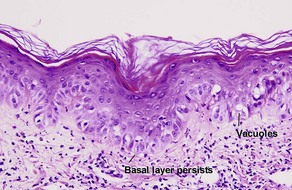

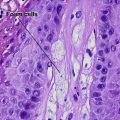

The biopsy in each of these conditions demonstrates a sawtooth rete ridge pattern with destruction of the basal layer, a band-like lymphoid infiltrate, and presence of Civatte bodies. Compact hyperkeratosis and beaded hypergranulosis are typically present. The cells of the stratum spinosum are enlarged and more eosinophilic than the normal epidermis. Vacuoles may be present in the lowest cells of stratum spinosum, but the basal layer is gone. An underlying band-like lymphoid infiltrate is common.

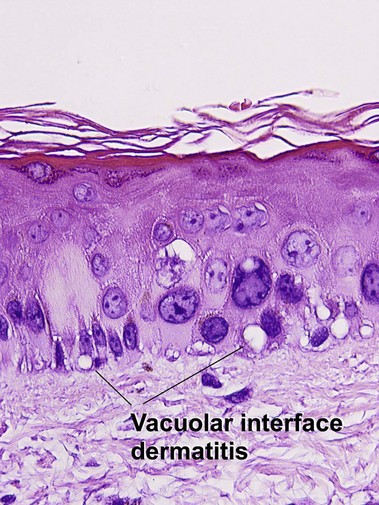

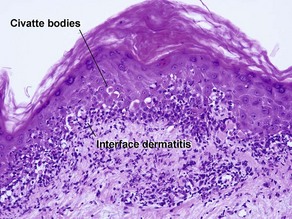

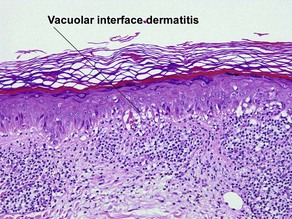

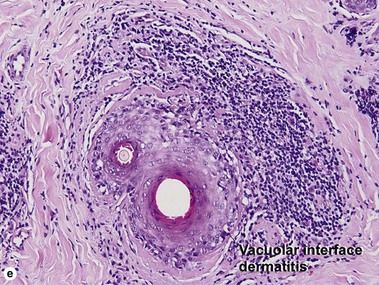

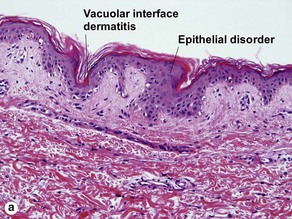

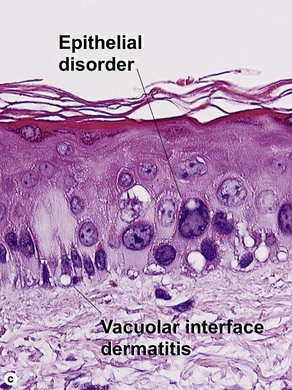

Vacuolar interface dermatitis

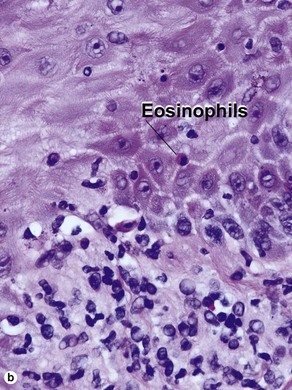

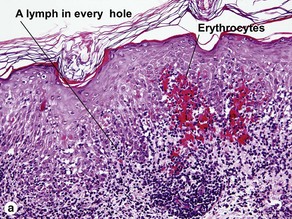

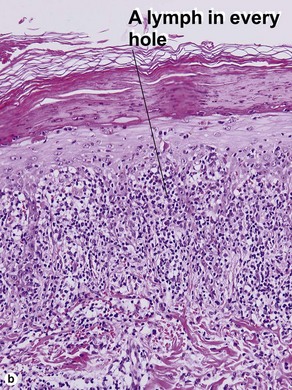

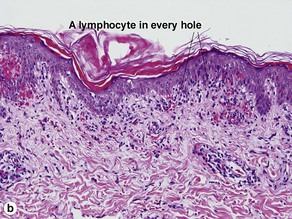

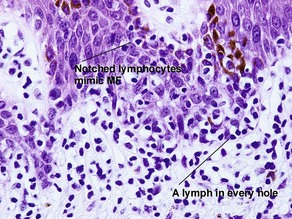

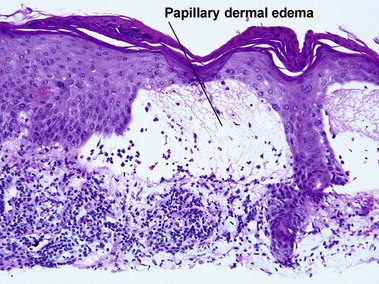

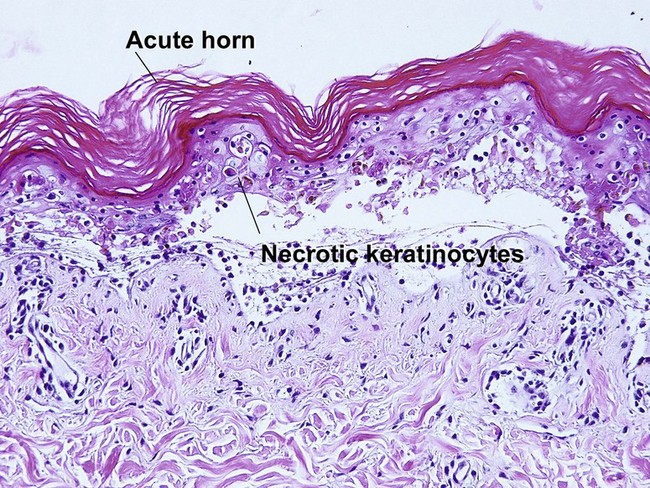

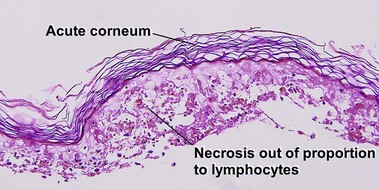

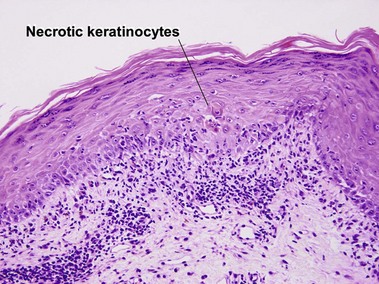

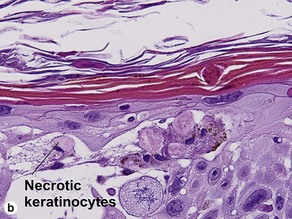

Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA)

The biopsy demonstrates vacuolar interface dermatitis with a lymphocyte in every vacuole. Keratinocyte necrosis, central ulceration, and crusting may be noted. Erythrocyte extravasation with transepidermal elimination of erythrocytes is common. The infiltrate is purely lymphoid, with a superficial and deep perivascular pattern. Prominent intravascular margination of neutrophils is typical. The infiltrate in PLEVA is characterized by CD8-positive cytotoxic T cells. A clone can often be detected by gene rearrangement studies.

Early stage of benign lichenoid keratosis

Vacuolar interface dermatitis with vacuoles or cell death out of proportion to lymphocytes

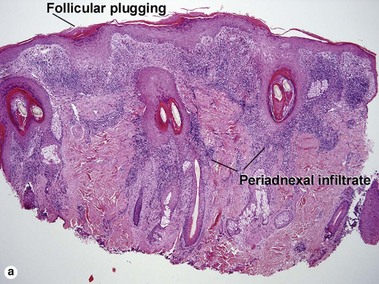

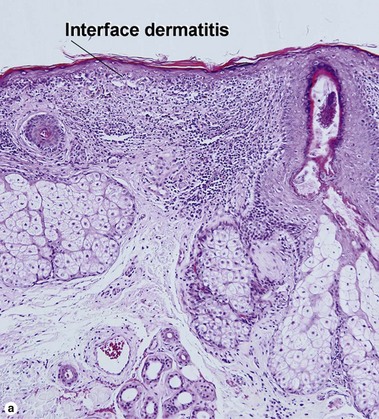

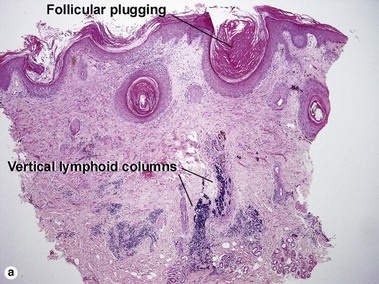

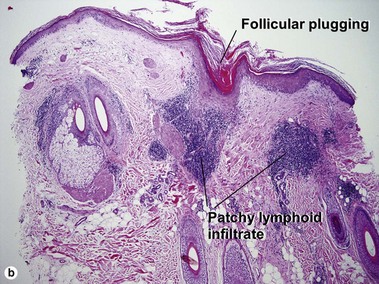

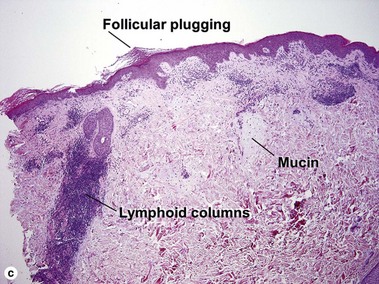

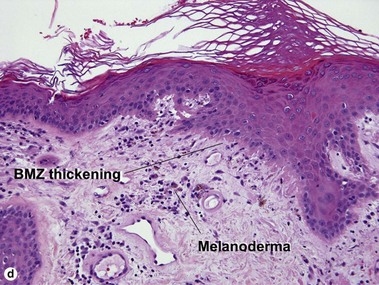

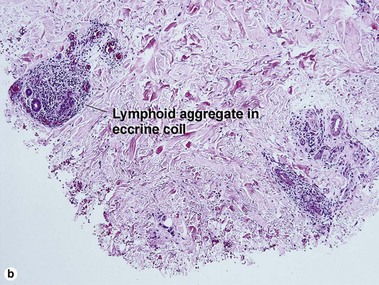

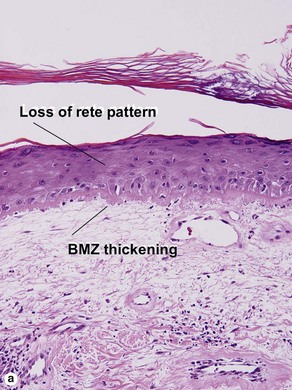

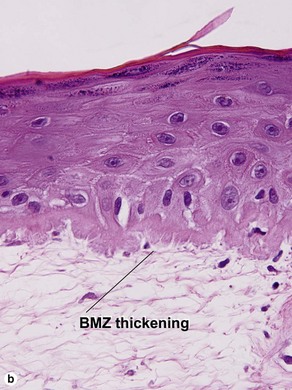

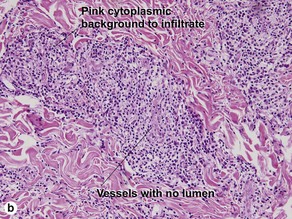

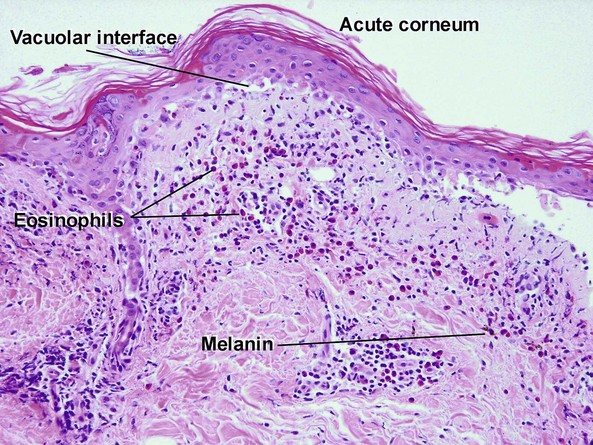

Lupus erythematosus

The features of discoid lupus erythematosus appear in a time-dependent fashion. Biopsies of acute lupus erythematosus show only vacuolar interface dermatitis. DIF will usually be negative at this stage. Subacute lesions of lupus erythematosus show vacuolar interface dermatitis, hyperkeratosis, and follicular plugging, as well as a variable dermal infiltrate. DIF is positive in about one-third of cases. Well-established discoid lesions (of at least 3 months’ duration) typically demonstrate strong DIF. Histologically, established discoid lupus erythematosus lesions are characterized by hyperkeratosis, follicular plugging, vacuolar interface dermatitis, basement membrane zone thickening, a patchy superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphoid infiltrate, and interstitial mucin. Underlying lupus panniculitis may be present.

Acikalin, A, Bagir, E, Tuncer, I, et al. Contribution of T-cell receptor gamma gene rearrangement by polymerase chain reaction and immunohistochemistry to the histological diagnosis of early mycosis fungoides. Saudi Med J. 2013; 34(1):19–23.

Brönnimann, M, Yawalkar, N. Histopathology of drug-induced exanthems: is there a role in diagnosis of drug allergy? Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005; 5(4):317–321.

Dalton, SR, Chandler, WM, Abuzeid, M, et al. Eosinophils in mycosis fungoides: an uncommon finding in the patch and plaque stages. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012; 34(6):586–591.

Dalton, SR, Fillman, EP, Altman, CE, et al. Atypical junctional melanocytic proliferations in benign lichenoid keratosis. Hum Pathol. 2003; 34(7):706–709.

Demartini, CS, Dalton, MS, Ferringer, T, et al. Melan-A/MART-1 positive “pseudonests” in lichenoid inflammatory lesions: an uncommon phenomenon. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005; 27(4):370–371.

Kaley, J, Pellowski, DM, Cheung, WL, et al. The spectrum of histopathologic findings in cutaneous eruptions associated with influenza A (H1N1) infection. J Cutan Pathol. 2013; 40(2):226–229.

Massone, C, Kodama, K, Kerl, H, et al. Histopathologic features of early (patch) lesions of mycosis fungoides: a morphologic study on 745 biopsy specimens from 427 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005; 29(4):550–560.

Morgan, MB, Stevens, GL, Switlyk, S. Benign lichenoid keratosis: a clinical and pathologic reappraisal of 1040 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005; 27(5):387–392.

Smith, SB, Libow, LF, Elston, DM, et al. Gloves and socks syndrome: early and late histopathologic features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002; 47(5):749–754.

Yawalkar, N, Pichler, WJ. Immunohistology of drug-induced exanthema: clues to pathogenesis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001; 1(4):299–303.

Zhang, Y, Wang, Y, Yu, R, et al. Molecular markers of early-stage mycosis fungoides. J Invest Dermatol. 2012; 132(6):1698–1706.