Chapter 338 Inguinal Hernias

Embryology and Pathogenesis

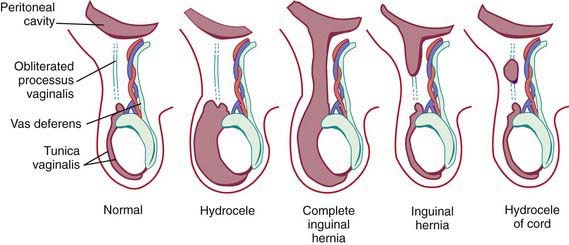

Androgenic hormones, adequate end-organ receptors, and mechanical factors such as increased intra-abdominal pressure influence complete descent of the testis through the inguinal canal. The testes and spermatic cord structures (spermatic vessels and vas deferens) are located in the retroperitoneum but are affected by increases in intra-abdominal pressure as a consequence of their intimate attachment to the processus vaginalis. The genitofemoral nerve also has an important role: It innervates the cremaster muscle, which develops within the gubernaculum, and experimental division or injury to both nerves in the fetus prevents testicular descent. Failure of regression of smooth muscle (present to provide the force for testicular descent) might have a role in the development of indirect inguinal hernias. Several studies have investigated genes involved in the control of testicular descent for their role in closure of the patent processus vaginalis, for example, hepatocyte growth factor and calcitonin gene-related peptide. Unlike in adult hernias, there does not appear to be any change in collagen synthesis associated with inguinal hernias in children (Fig. 338-1).

Pathology

A hydrocele is when only fluid enters the patent processus vaginalis and the swelling may exist only in the scrotum (scrotal hydrocele), only along the spermatic cord in the inguinal region (hydrocele of the spermatic cord), or extend from the scrotum through the inguinal canal and even into the abdomen (abdominal-scrotal hydrocele). A hydrocele is termed a communicating hydrocele if it demonstrates fluctuation in size, often increasing in size after activity and, at other times, being smaller when the fluid decompresses into the peritoneal cavity. Occasionally, hydroceles in older children follow trauma, inflammation, or tumors affecting the testis. Although reasons for failure of closure of the processus vaginalis are unknown, it is more common in cases of testicular nondescent and prematurity. In addition, persistent patency of the processus vaginalis is twice as common on the right side, presumably related to later descent of the right testis and interference from the developing inferior vena cava and external iliac vein. Risk factors identified as contributing to the development of congenital inguinal hernia relate to conditions that predispose to failure of obliteration of the processus vaginalis and are listed in Table 338-1. Incidence of inguinal hernia in patients with cystic fibrosis is ~15%, believed to be related to an altered embryogenesis of the wolffian duct structures, which leads to an absent vas deferens in males with this condition. There is also an increased incidence of inguinal hernia in patients with testicular feminization syndrome and other forms of ambiguous genitalia. The rate of recurrence after repair of an inguinal hernia in patients with a connective tissue disorder approaches 50%, and often the diagnosis of connective tissue disorders in children results from investigation after development of a recurrent inguinal hernia.

Evaluation of Acute Inguinal-Scrotal Swelling

Ambiguous Genitalia

Infants with disorders of sexual development commonly present with inguinal hernias, often containing a gonad, and require special consideration. In female infants with inguinal hernias, particularly if the presentation is bilateral inguinal masses, testicular feminization syndrome should be suspected because >50% of patients with testicular feminization have an inguinal hernia (Chapter 577). Conversely, the true incidence of testicular feminization in all female infants with inguinal hernias is difficult to determine but is ~1%. In phenotypic females, if the diagnosis of testicular feminization is suspected preoperatively, the child should be screened with a buccal smear for Barr bodies and appropriate genetic evaluation before proceeding with the hernia repair. The diagnosis of testicular feminization is occasionally made at the time of operation by identifying an abnormal gonad (testis) within the hernia sac or absence of the uterus on rectal examination. In the normal female infant, the uterus is easily palpated as a distinct midline structure beneath the symphysis pubis on rectal examination. Preoperative diagnosis of testicular feminization syndrome or other disorders of sexual development such as mixed gonadal dysgenesis and selected pseudohermaphrodites enables the family to receive counseling, and gonadectomy can be accomplished at the time of the hernia repair.

Management

The operation is most often performed under general anesthesia, but it can be performed under spinal or caudal anesthesia if avoidance of intubation is preferable due to chronic lung disease or bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Prophylactic antibiotics are not routinely used except for associated conditions such as congenital heart disease or the presence of a venticuloperitoneal shunt. Preterm infants mandate special consideration because of their higher risk for apnea and bradycardia after general anesthesia (Chapter 70). Infants <44 wk postconceptional age and full-term infants <3 mo of age and with comorbid conditions should be observed overnight with appropriate apnea and cardiorespiratory monitors.

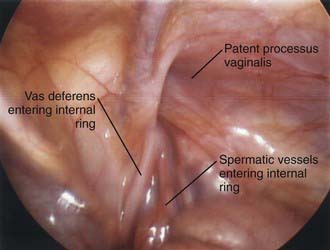

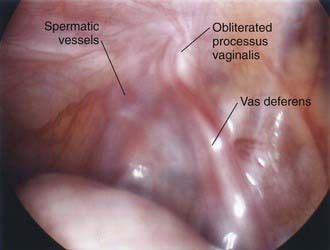

Contralateral Inguinal Exploration

Laparoscopy enables assessment of the contralateral side without risk of injury to the spermatic cord structures or testis. This procedure can be performed through an umbilical incision or by passing a 30-degree or 70-degree oblique scope through the open hernia sac just before ligation of the hernia sac on the involved side. If patency of the contralateral side is demonstrated, the surgeon can proceed with bilateral hernia repair, and if the contralateral side is properly obliterated, exploration and potential complications are avoided. The downside of this approach is that laparoscopy cannot differentiate between a patent processus vaginalis and a true hernia (Figs. 338-2 and 338-3).

Complications

Gallagher TM. Regional anesthesia for surgical treatment of inguinal hernia in preterm babies. Arch Dis Child. 1993;69:623-624.

Geiger JD. Selective laparoscopic probing for a contralateral patent processus vaginalis reduces the need for contralateral exploration in inconclusive cases. J Pediatr Surg. 2000;35:1151-1154.

Holcomb GW. Laparoscopic evaluation for a contralateral inguinal hernia or a nonpalpable testis. Pediatr Ann. 1993;22:678-684.

Hosgor M, Karaca I, Ozer E, et al. Do alterations in collagen synthesis play an etiologic role in childhood inguinoscrotal pathologies: an immunohistochemical study. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:1024-1029.

Jenkins JT, O’Dwyer PJ. Inguinal hernias. BMJ. 2008;336:269-272.

Lobe TE, Schropp KP. Inguinal hernias in pediatrics: initial experience with laparoscopic inguinal exploration of the asymptomatic contralateral side. J Laparoendosc Surg. 1992;2:135-140.

Luo CC, Chao HC. Prevention of unnecessary contralateral exploration using the silk glove sign (SGS) in pediatric patients with unilateral inguinal hernia. Eur J Pediatr. 2007;166:667-669.

Manoharan S, Samarakkody U, Kulkarni M, et al. Evidence-based change of practice in the management of unilateral inguinal hernia. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:163-166.

Marulaiah M, Atkinson J, Kukkady A, et al. Is contralateral exploration necessary in preterm infants with unilateral inguinal hernia? J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:2004-2007.

Owings EF, Georgeson KE. A new technique for laparoscopic exploration to find contralateral patent processus vaginalis. Surg Endosc. 2000;14:114-116.

Rescorla FJ. Hernias and umbilicus. In: Oldham KT, Colambani PM, Foglia RP, et al, editors. Principles and practice of pediatric surgery. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005:1087-1101.

Rowe MI, Copelson LW, Clatworthy HW. The patent processus vaginalis and the inguinal hernia. J Pediatr Surg. 1969;4:102-107.

Shier F, Montupet P, Esposito C. Laparoscopic inguinal herniorrhaphy in children: a three center experience with 933 repairs. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:395-397.

Skandalakis JE, Gray SW. Embryology for surgeons: the embryologic basis for the treatment of congenital anomalies, ed 2. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1994. pp 184–241

Spurbeck WW, Prasad R, Lobe TE. Two year experience with minimally invasive herniorrhaphy in children. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:551-553.

Stergman C, Sotelo-Avila C, Weber TR. The incidence of spermatic cord structures in inguinal hernia sacs from male children. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:883-885.

Tacket LD, Breuer CK, Luks FI, et al. Incidence of contralateral inguinal hernia: a prospective analysis. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34:684-687.

Tanyel FC, Dagdeviren A, Muftuoglu S, et al. Inguinal hernia revisited through comparative evaluation of peritoneum, processus vaginalis, and sacs obtained from children with hernia, hydrocele, and undescended testis. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34(4):552-555.

Tanyel FC, Okur HD. Autonomic nervous system appears to play a role in obliteration of processus vaginalis. Hernia. 2004;8(2):149-154.

Weber TR, Tracy TFJr, Keller MS. Groin hernias and hydroceles. In: Ashcraft KW, Holcomb GWIII, Murphy JP, editors. Pediatric surgery. ed 4. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2005:697-705.

Wiener ES, Touloukian RJ, Rodgers BM, et al. Hernia survey of the Section on Surgery of the American Academy of Pediatrics. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31:1166-1169.

Zamakhshary M, To T, Guan J, et al. Risk of incarceration of inguinal hernia among infants and young children awaiting elective surgery. CMAJ. 2008;179:1001-1005.