Inflammatory vascular diseases

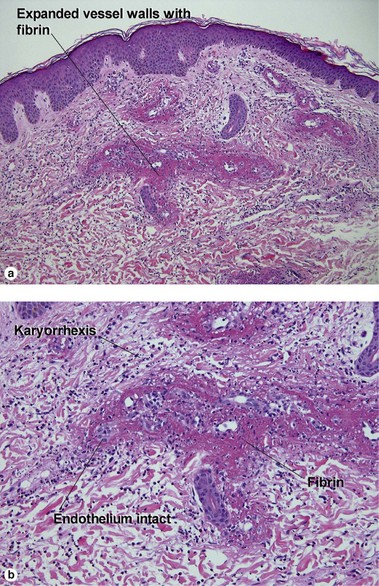

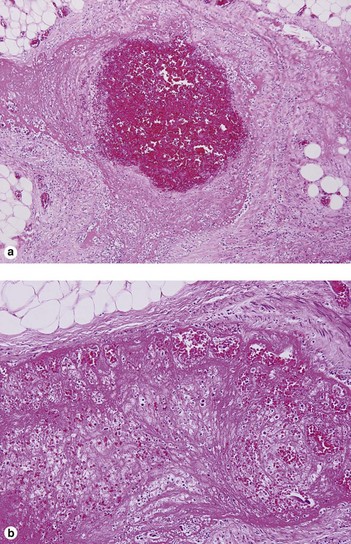

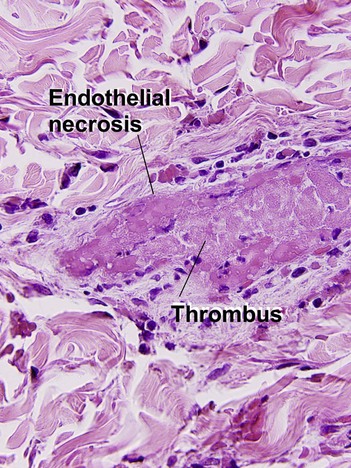

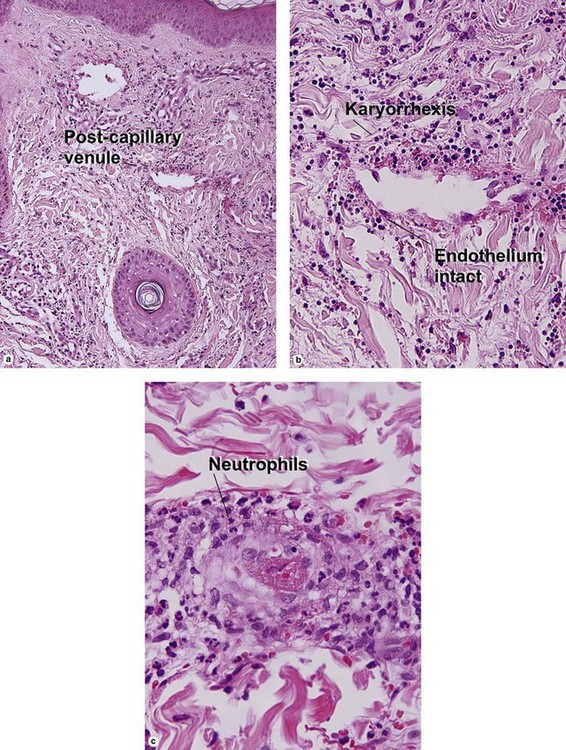

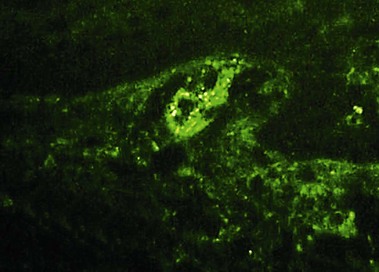

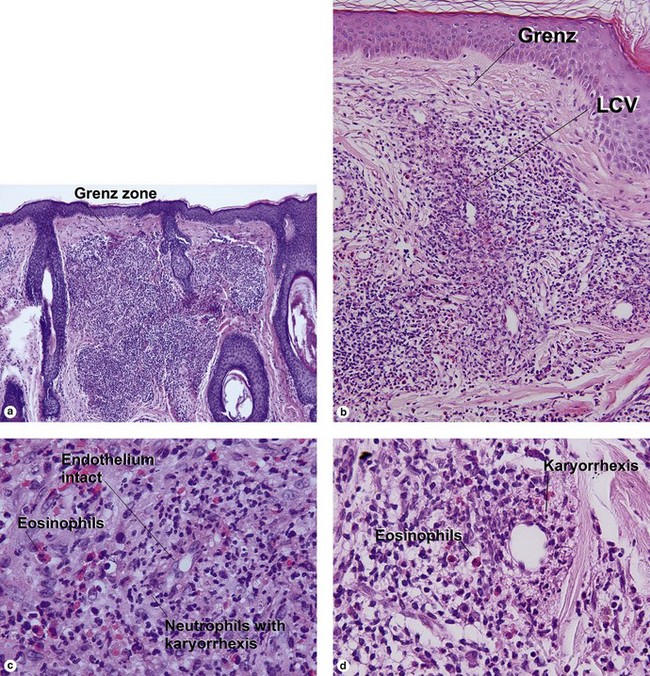

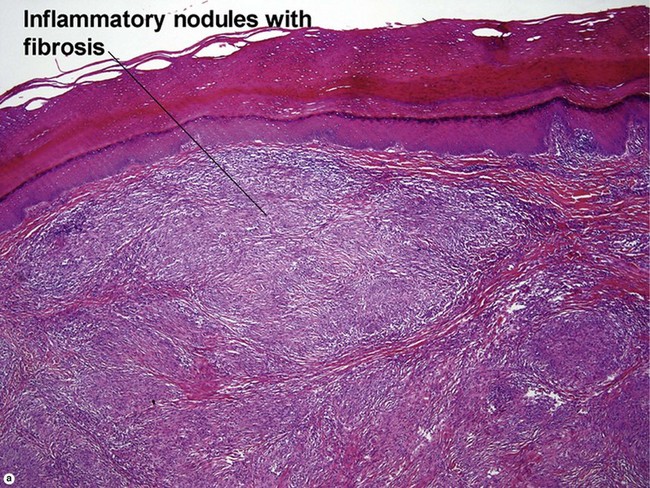

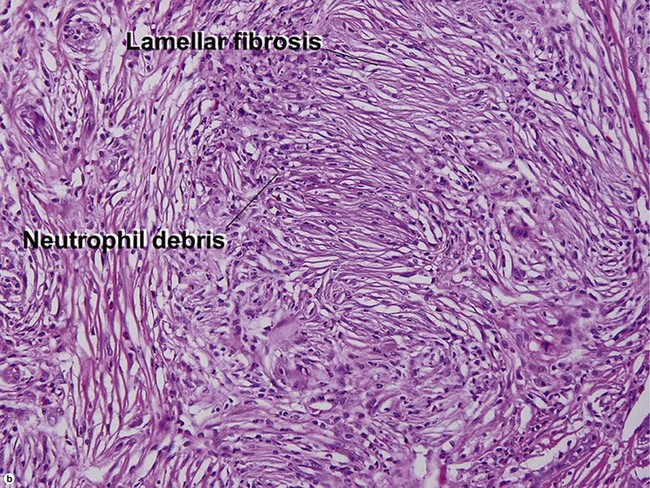

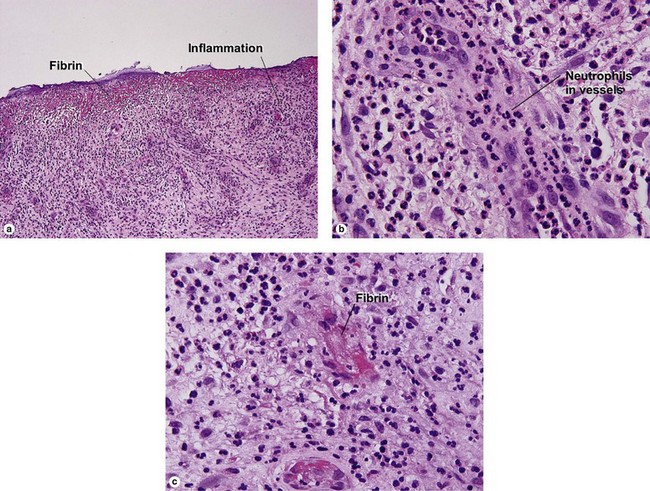

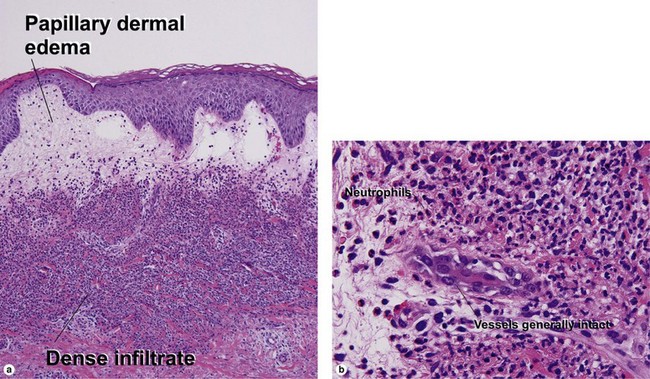

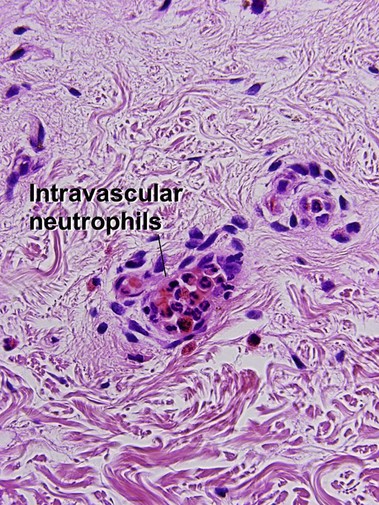

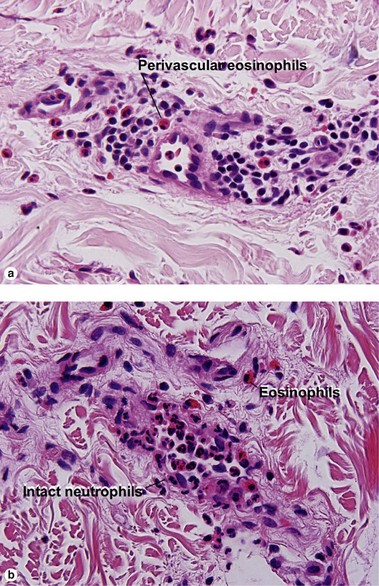

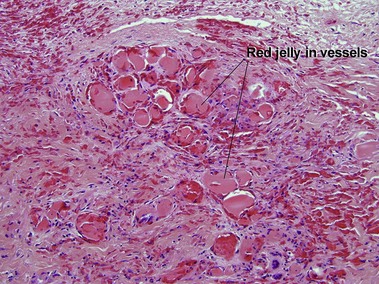

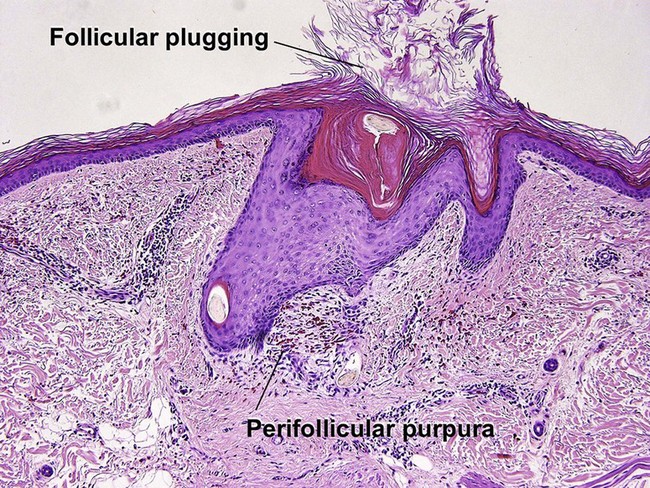

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV)

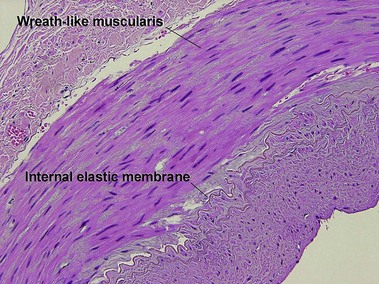

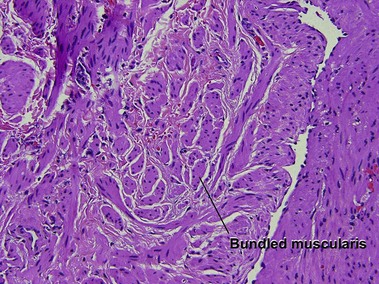

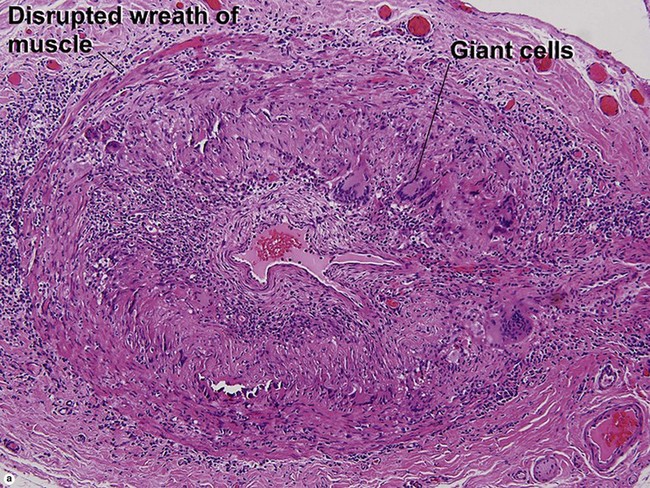

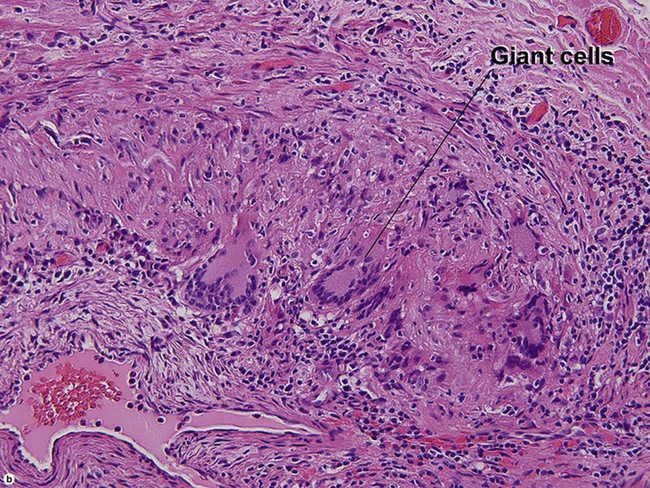

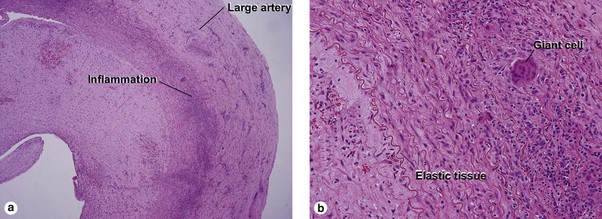

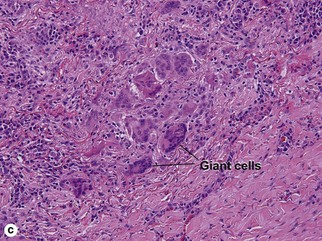

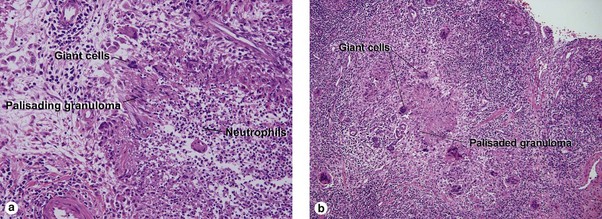

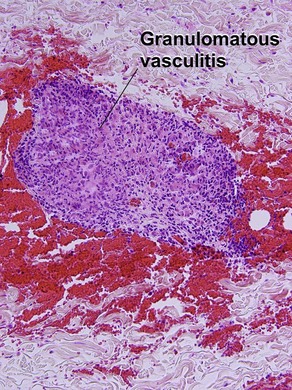

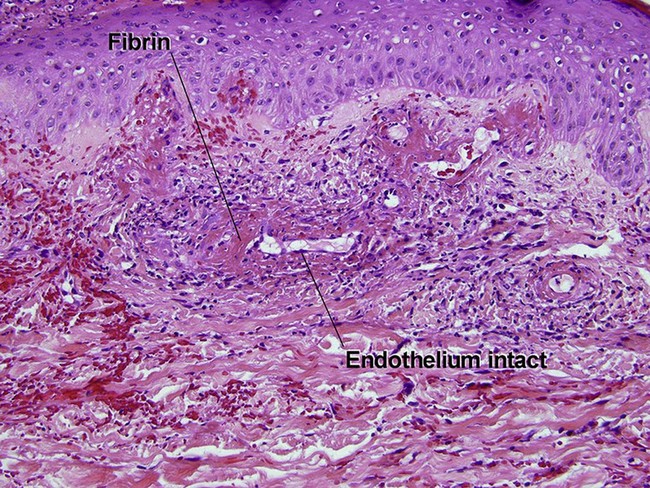

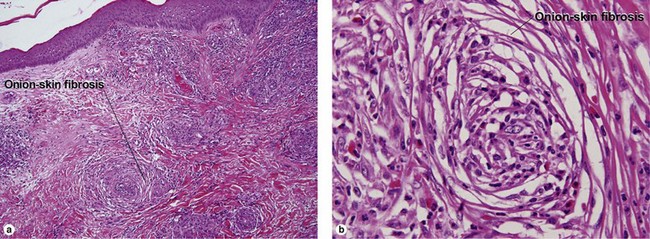

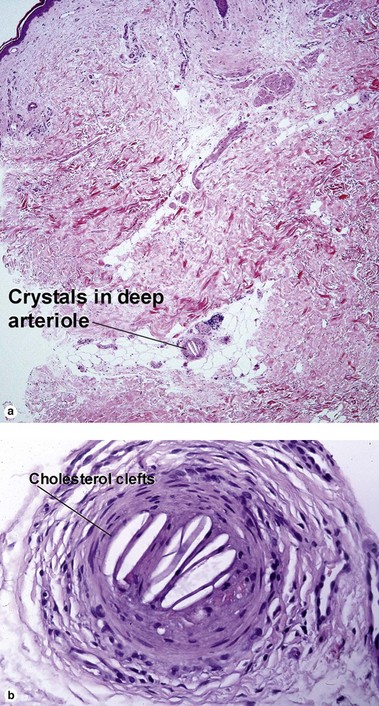

Large vessel vasculitis

Takayasu arteritis

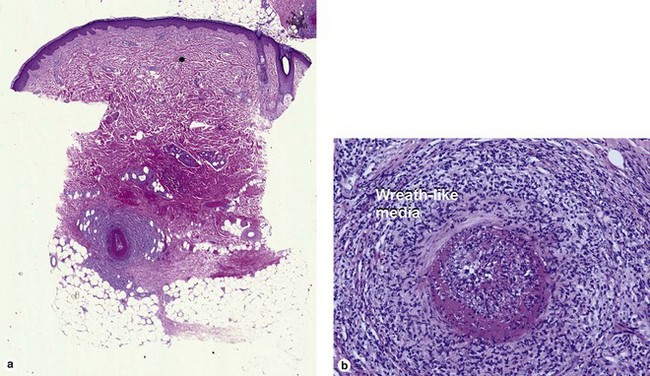

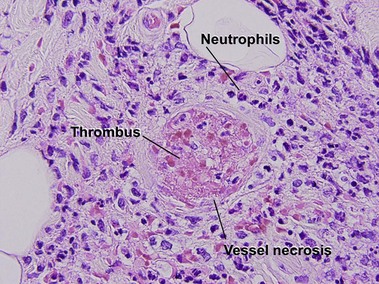

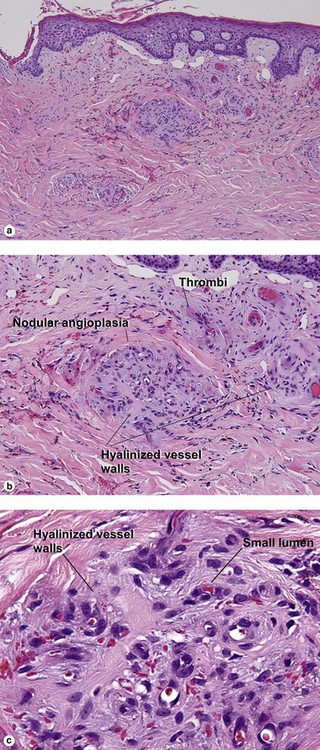

Medium vessel vasculitis

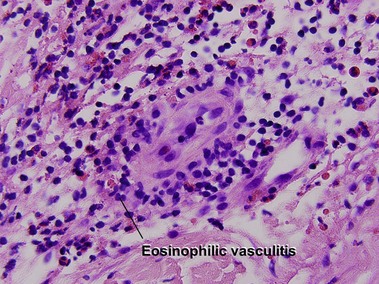

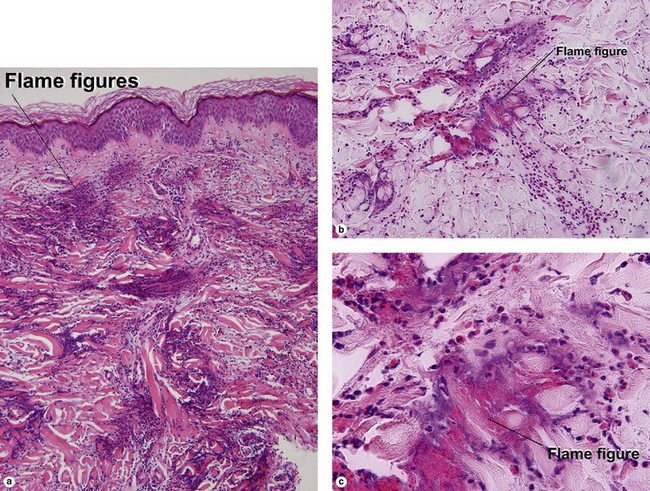

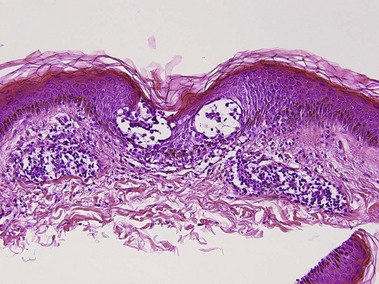

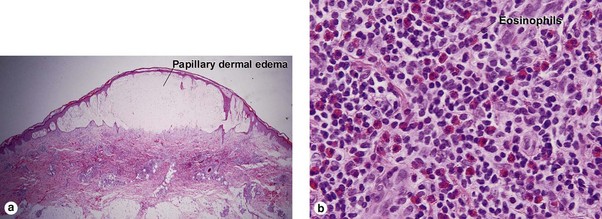

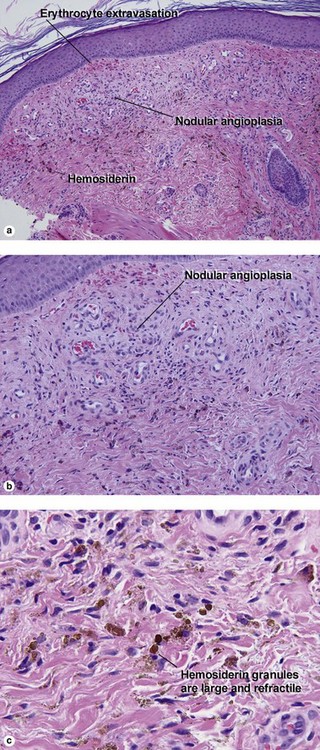

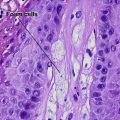

Small vessel leukocytoclastic vasculitis

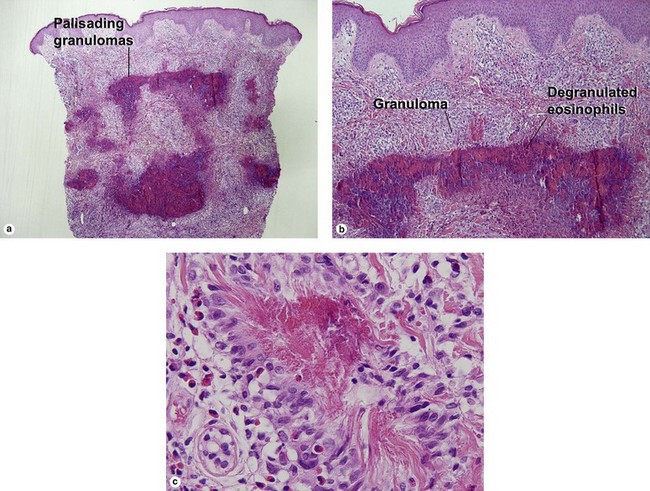

Unique forms of vasculitis

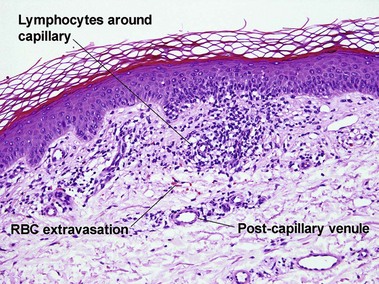

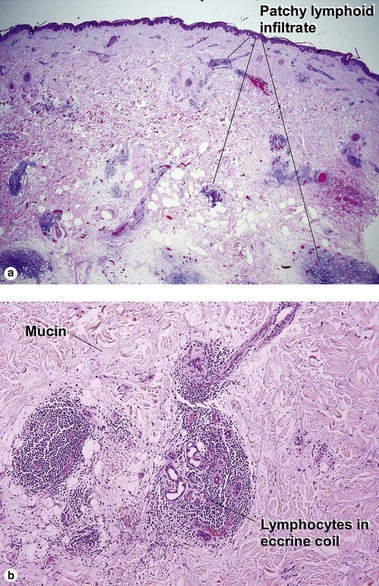

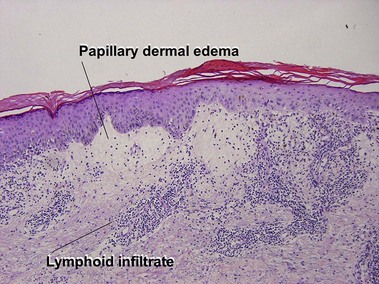

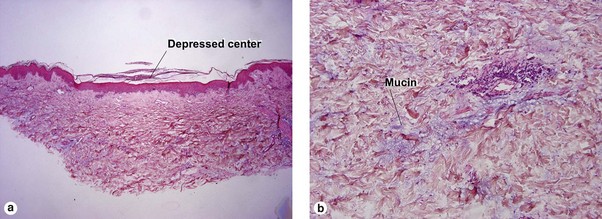

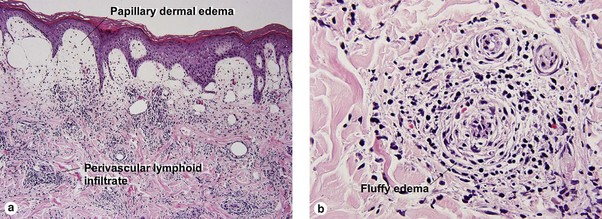

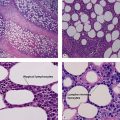

Perivascular lymphoid infiltrates

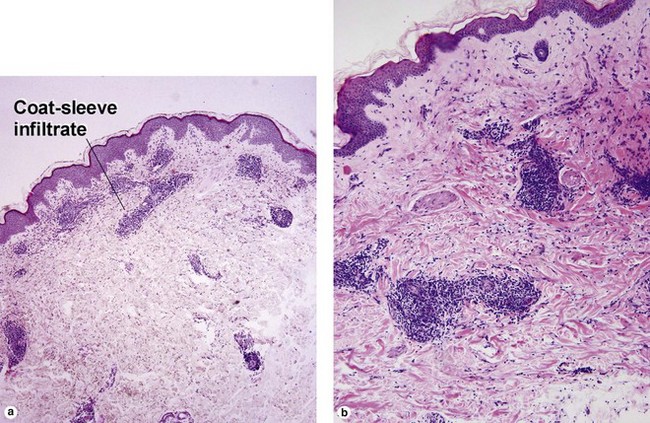

Lymphoid vasculitis

Bertoli, AM, Alarcón, GS. Classification of the vasculitides: are they clinically useful? Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2005; 7(4):265–269.

Carlson, JA, Ng, BT, Chen, KR. Cutaneous vasculitis update: diagnostic criteria, classification, epidemiology, etiology, pathogenesis, evaluation and prognosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005; 27(6):504–528.

Knütter, I, Hiemann, R, Brumma, T, et al. Automated interpretation of ANCA patterns – a new approach in the serology of ANCA-associated vasculitis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012; 14(6):R271.

Lionaki, S, Blyth, ER, Hogan, SL, et al. Classification of antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody vasculitides: the role of antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody specificity for myeloperoxidase or proteinase 3 in disease recognition and prognosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2012; 64(10):3452–3462.

Ozen, S. Problems in classifying vasculitis in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005; 20(9):1214–1218.

Pagnoux, C, Guillevin, L. Cardiac involvement in small and medium-sized vessel vasculitides. Lupus. 2005; 14(9):718–722.

Saleh, A, Stone, JH. Classification and diagnostic criteria in systemic vasculitis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2005; 19(2):209–221.

Watts, RA, Scott, DG. ANCA vasculitis: to lump or split? Why we should study MPA and GPA separately. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012; 51(12):2115–2117.