Infections of the Urinary Tract

1. Describe the anatomy and identify the structures of the urinary tract, for both males and females.

2. Name the organisms that colonize the urethra and are considered normal flora.

3. Explain how the female urinary tract anatomy may predispose women to urinary tract infections.

4. Differentiate between community-acquired urinary tract infections and hospital-acquired urinary tract infections.

5. List the routes of transmission that allow bacteria to invade and cause a urinary tract infection.

6. Name the physical and chemical properties of urine that contribute to its role in the body’s defense mechanism against the bacteria capable of causing urinary tract infections.

7. Explain host and microbial factors that determine whether bacteria will be able to colonize and cause a urinary tract infection.

8. Name the properties bacteria possess that predispose them to having greater pathogenicity in causing urinary tract infections.

9. Define the five major types of urinary tract infections: pyelonephritis, cystitis, urethritis, acute urethral syndrome, and asymptomatic bacteriuria.

10. Compare and contrast complicated and uncomplicated urinary tract infections.

11. Explain the collection methods for urine specimens, including clean catch midstream urine, straight catheterized urine, a suprapubic bladder aspiration, and an indwelling catheter collection.

12. Describe the urine-screening methods available to determine bacteriuria and pyuria.

13. Explain the nitrate reductase test, the leukocyte esterase test, and the catalase test in regard to their urine-screening capability.

14. Name the media required for urine cultures.

15. Explain the proper methodology for plating and interpreting a quantitative urine culture.

16. Correlate signs and symptoms with the results of laboratory diagnositc procedures for the identification of the etilogic agent associated with infections of the urinary tract.

General Considerations

Anatomy

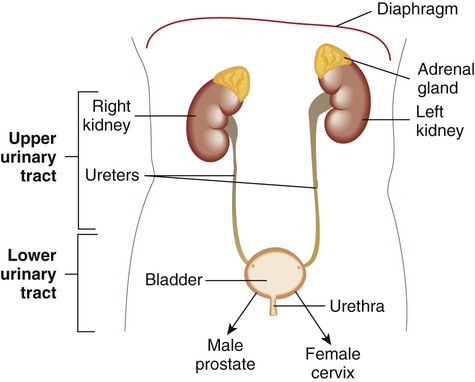

The urinary tract consists of the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra (Figure 73-1). The function of the urinary tract is to make and process urine. Urine is an ultrafiltrate of blood that consists mostly of water but also contains nitrogenous wastes, sodium, potassium, chloride, and other analytes. Urine is normally a sterile fluid, Often, urinary tract infections (UTIs) are characterized as being either upper (U-UTI) or lower (L-UTI) based primarily on the anatomic location of the infection: the lower urinary tract encompasses the bladder and urethra, and the upper urinary tract encompasses the ureters and kidneys. Upper urinary tract infections affect the ureters (ureteritis) or the renal parenchyma (pyelonephritis). Lower urinary tract infections may affect the urethra (urethritis), the bladder (cystitis), or the prostate in males (prostatitis).

Resident Microorganisms of the Urinary Tract

The urethra has resident microflora that colonize its epithelium in the distal portion; these organisms are lactobacilli, corynebacteria, and coagulase-negative staphylococci (Box 73-1). Potential pathogens, including gram-negative aerobic bacilli (primarily Enterobacteriaceae) and occasional yeasts, are also present as transient colonizers. All areas of the urinary tract above the urethra in a healthy human are sterile. Urine is typically sterile, but noninvasive methods for collecting urine must rely on a specimen that has passed through a contaminated milieu. Therefore, quantitative cultures for the diagnosis of UTIs have been used to discriminate among contamination, colonization, and infection.

Infections of the Urinary Tract

Epidemiology

Pathogenesis

Routes of Infection

The Host-Parasite Relationship

Activation of the host immune response by uropathogens also plays a key role in fending off infection. For example, bacterial contact with urothelial cells initiates an immune response via a variety of signaling pathways. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS; see Chapter 2) activates host cells to ultimately release cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor and interferon-gamma. In addition, bacteria can activate the complement cascade, leading to the production of biologically active components such as opsonins, as well as augment the host’s adaptive immune response. Host factors that lead to host susceptibility or resistance to uropathogens have been identified. For example, a glycoprotein synthesized exclusively by epithelial cells in a specific anatomic location in the kidney, referred to as Tamm-Horsfall protein or uromodulin, serves as an anti-adherence factor by binding to E. coli–expressing type 1 fimbriae (discussed later). Defensins, a group of small antimicrobial peptides, are produced by a variety of host cells such as macrophages, neutrophils, and cells in the urinary tract and attach to the bacterial cell, eventually causing its death.

Although many microorganisms can cause UTIs, most cases are a result of infection by a few organisms. To illustrate, only a limited number of serogroups of E. coli cause a significant proportion of UTIs. Numerous investigations indicate that UPEC possesses virulence factors that enhance their ability to colonize and invade the urinary tract. Some of these virulence factors include increased adherence to vaginal and uroepithelial cells by bacterial surface structures (adhesins, in particular, pili), alpha-hemolysin production, and resistance to serum-killing activity (Box 73-2). Also, genome sequences of some UPEC strains have been determined, indicating that several potential virulence factor genes associated with the acquisition and development of UTIs are encoded on pathogenicity islands (e.g., hemolysins and E. coli P. fimbriae). Uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) possess pathogenicity islands containing a variety of virulence factors. By definition, pathogenicity islands (see Chapter 3) contain genes that are associated with virulence and are absent from avirulent or less virulent strains of the same species.

Types of Infection and Their Clinical Manifestations

UTI encompasses a broad range of clinical entities that differ in terms of clinical presentation, degree of tissue invasion, epidemiologic setting, and requirements for antibiotic therapy. There are several types of UTIs: urethritis, ureteritis, asymptomatic bacteriuria, cystitis, the urethral syndrome, and pyelonephritis. Sometimes UTIs are classified as uncomplicated or complicated. Uncomplicated infections occur primarily in otherwise healthy females and occasionally in male infants and adolescent and adult males. Most uncomplicated infections respond readily to antibiotic agents to which the etiologic agent is susceptible. Complicated infections occur in both sexes. In general, individuals who develop complicated infections often have certain risk factors. Some of these risk factors are listed in Box 73-3. In general, complicated infections are more difficult to treat and have greater morbidity (e.g., kidney damage, bacteremia) and mortality compared with uncomplicated infections.

Urethritis

Symptoms associated with urethritis (infection of the urethra), dysuria (painful or difficult urination), and frequency are similar to those associated with lower UTIs. Urethritis is a common infection. Because Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Trichomonas vaginalis are common causes of urethritis and considered to be sexually transmitted, urethritis is discussed as a sexually transmitted disease in Chapter 74.

Laboratory Diagnosis of Urinary Tract Infections

As previously mentioned, because noninvasive methods for collecting urine must rely on a specimen that has passed through a contaminated milieu, quantitative cultures for the diagnosis of UTI are used to discriminate between contamination, colonization, and infection. Refer to Table 5-1 for a quick reference for collecting, transporting, and processing urinary tract specimens.

Specimen Collection

Straight Catheterized Urine

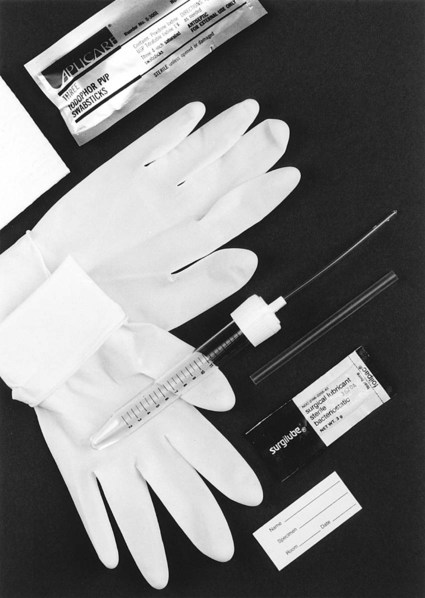

Although slightly more invasive, urinary catheterization provides a method for the collection of uncontaminated urine from the bladder. Either a physician or another trained health professional performs this procedure. Risk exists, however, that urethral organisms will be introduced into the bladder with the catheter. An example of a collection device to obtain “straight,” or “in and out,” catheterized urine is shown in Figure 73-2.

Screening Procedures

General Comments Regarding Screening Procedures

Other factors that must be considered when selecting a rapid urine screen include accuracy, ease of test performance, reproducibility, turnaround time, and whether bacteriuria or pyuria is detected.

Urine Culture

Inoculation and Incubation of Urine Cultures

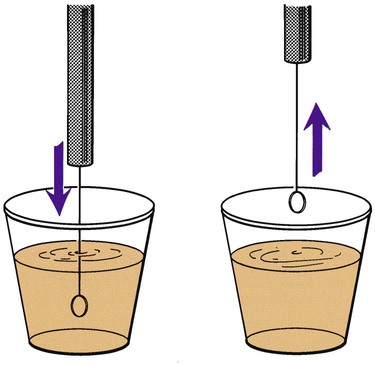

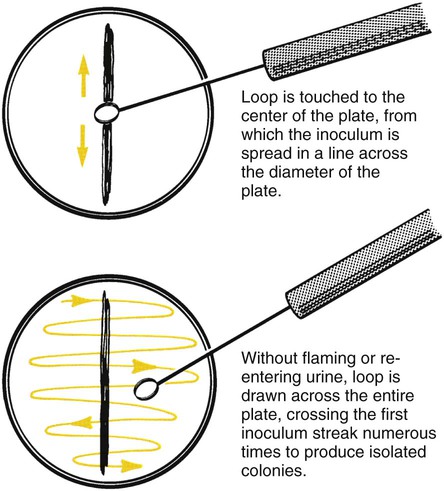

Before inoculation, urine is mixed thoroughly and the top of the container is then removed. The calibrated loop is inserted vertically into the urine in a cup. Otherwise, more than the desired volume of urine will be taken up, potentially affecting the quantitative culture result (Figure 73-3). A widely used method is described in Procedure 73-1, which can be found on the Evolve site. If the urine is in a small-diameter tube, the surface tension will alter the amount of specimen picked up by the loop. A quantitative pipette should be considered if the urine cannot be transferred to a larger container. Once inoculated, the plates are streaked to obtain isolated colonies (Figure 73-4).

Interpretation of Urine Cultures

One major problem in interpreting urine cultures arises because urine cultures collected by the voided technique may be contaminated with normal flora, including Enterobacteriaceae. Determining what colony count represents true infection from contamination is of utmost importance and is related to the patient’s clinical presentation. A number of studies have proposed the use of different cutoffs in colony counts based on clinical presentation; an example of one such set of guidelines is given in Table 73-1.

TABLE 73-1

Criteria for Classification of Urinary Tract Infections by Clinical Syndrome

| Category | Clinical | Laboratory |

| Acute, uncomplicated UTI in women | Dysuria, urgency, frequency, suprapubic pain No urinary symptoms in last 4 weeks before current episode No fever or flank pain |

≥10 WBC/mm3 ≥103 CFU/mL uropathogens* in CCMS urine |

| Acute, uncomplicated pyelonephritis | Fever, chills Flank pain on examination Other diagnoses excluded No history or clinical evidence of urologic abnormalities |

≥10 WBC/mm3 ≥104 CFU/mL uropathogens in CCMS urine |

| Complicated UTI and UTI in men | Any combination of symptoms listed above One or more factors associated with complicated UTI† |

≥10 WBC/mm3 ≥105 CFU/mL uropathogens in CCMS urine |

| Asymptomatic bacteriuria | No urinary symptoms | ± >10 WBC/mm3 ≥105 CFU/mL in two CCMS cultures >24 hours apart |

UTI, Urinary tract infection; WBC, white blood cells; CFU, colony-forming unit; CCMS, clean-catch midstream urine.

*Uropathogens: Organisms that commonly cause UTIs.

From Stamm WE: Criteria for the diagnosis of urinary tract infection and for the assessment of therapeutic effectiveness, Infection 20 (suppl 3):S151, 1992.

Ideally, the clinician caring for the patient should provide the laboratory with enough clinical information to allow specimens from different patient populations to be identified. These specimens could then be selectively processed using the guidelines in Table 73-1. However, because microbiology laboratories frequently receive little or no clinical information about patients, questions have been raised as to whether these cutoffs are practical and realistic for routine laboratory use. Further complicating urine culture interpretation is the increasing difficulty in distinguishing between infection and contamination as the criterion for a positive culture is lowered from 105 CFU/mL to 102 CFU/mL. Because of these issues, many laboratories establish their own interpretative criteria for urine cultures based on the type of urine submitted (e.g., clean-catch midstream, catheterized, and surgically obtained specimens such as suprapubic aspirates). Variations in interpretative guidelines occur from one laboratory to another but some generalities can be made; these are listed in Table 73-2. Some examples of urine culture results are shown in Figure 73-5 to illustrate some of these interpretations. See the Evolve site for a semi-quantitative procedure for inoculation of urine cultures.

TABLE 73-2

General Interpretative Guidelines for Urine Cultures

| Result | Specific Specimen Type/Associated Clinical Condition, if Known | Workup |

| ≥104 CFU/mL of a single potential pathogen or for each of two potential pathogens | CCMS urine/pyelonephritis, acute cystitis, asymptomatic bacteriuria, or catheterized urines | Complete* |

| ≥103 CFU/mL of a single potential pathogen | CCMS urine/symptomatic males or catheterized urines or acute urethral syndrome | Complete |

| ≥Three organism types with no predominating organism | CCMS urine or catheterized urines | None; because of possible contamination, ask for another specimen |

| Either two or three organism types with predominant growth of one organism type and <104 CFU/mL of the other organism type(s) | CCMS urine | Complete workup for the predominating† organism(s); description of the organism(s) |

| ≥102 CFU/mL of any number of organism types (set up with a 0.001- and 0.01-mL calibrated loop) | Suprapubic aspirates, any other surgically obtained urines (including ileal conduits, cystoscopy specimens) | Complete |

CFU, colony-forming unit; CCMS, clean-catch midstream urine.

*A complete workup includes identification of the organism and appropriate susceptibility testing.