Infections of the Respiratory System

After reading this chapter, the student will be able to:

• Name the criteria necessary for microbes to cause an infection of the respiratory system

• Identify the microbes typically present in the normal flora of the respiratory tract

• Name the different streptococcal respiratory infections; describe the transmission, symptoms, and treatment for each

• Discuss drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae disease

• Describe the transmission and treatment of mycoplasmal and chlamydial pneumonias

• Discuss pertussis, tuberculosis, and their treatments

• Describe rare and opportunistic respiratory infections caused by bacteria

• Compare and contrast the common cold and influenza, and their prevention and treatment

• Describe infections of the respiratory system caused by fungi and the treatment of their infections

• Describe the common symptoms of upper and lower respiratory system infections, the possible treatments, and prevention

Introduction

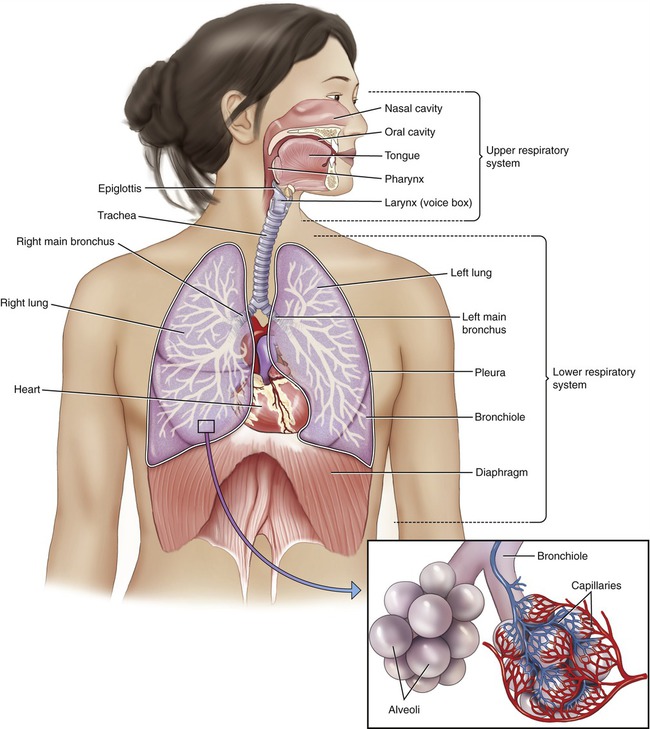

The respiratory tract consists of the nasal cavity, the pharynx, larynx, bronchial tree, and lungs. Structurally and functionally the system can be divided into upper and lower respiratory systems (Figure 11.1).

The respiratory tract can be divided into the upper respiratory system, including the nose, pharynx, and associated structures; and the lower respiratory system, consisting of the larynx, trachea, bronchi, and lungs.

• The upper respiratory system includes the nose, pharynx, and associated structures.

• The lower respiratory system consists of the larynx, trachea, bronchi, and lungs.

The lining of the respiratory tract is a mucosal epithelium that serves as a barrier against microbial invasion; however, it is not as effective as an intact skin barrier. The mucosal lining of the respiratory tract has a moist and relatively warm environment suitable for microbes. Moreover, microbes may be trapped in the mucous layer and by way of the ciliary escalator transported to the pharynx and then swallowed. The normal flora (see Chapter 9, Infection and Disease) of the respiratory system contains a large number of bacteria that help to maintain a healthy state of the host by competing with potential pathogenic organisms. The microorganisms of the normal flora are usually harmless but they can become opportunistic pathogens when the host immune system is depressed, or when damage occurs to the mucosal membrane. Infections of the respiratory system can be caused by bacteria, viruses, and fungi. For an infection of the respiratory system to occur due to an exogenous agent the following criteria must be met:

• A sufficient number (dose) of infectious agent must be inhaled.

• The infectious agents must be airborne or contained in droplet nuclei.

• The infectious organism must remain alive and viable while in the air.

• The organism must find susceptible tissue in the host, suitable for attachment and growth.

• Once in the respiratory tract the organism must colonize the surfaces before it can cause disease.

Bacterial Infections

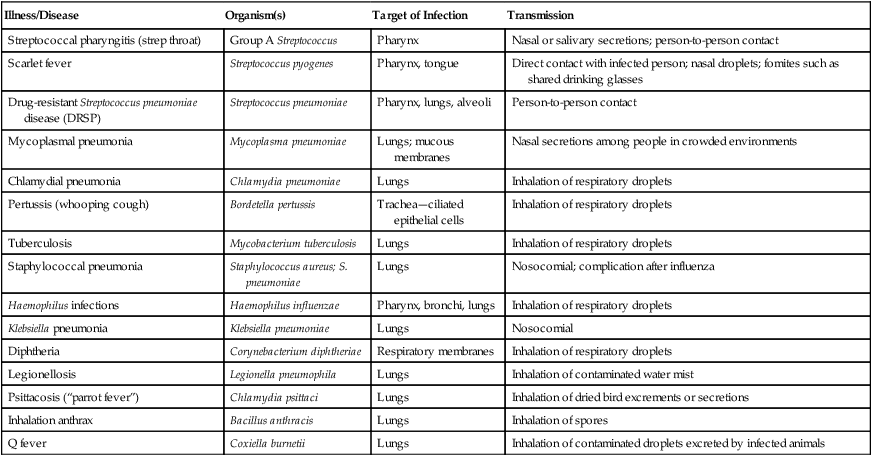

Bacterial infections of the respiratory tract can be caused by Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Klebsiella, Haemophilus, Bordetella, Corynebacterium, Mycobacterium, Legionella, Mycoplasma, Chlamydia, and Coxiella. Infections caused by inhabitants of the normal flora can occur and appear as secondary infections after damage to the mucosal lining, usually caused by a viral infection such as the common cold. A summary of bacterial infections acquired through the respiratory system is given in Table 11.1.

TABLE 11.1

Bacterial Infections Acquired Through the Respiratory Tract

| Illness/Disease | Organism(s) | Target of Infection | Transmission |

| Streptococcal pharyngitis (strep throat) | Group A Streptococcus | Pharynx | Nasal or salivary secretions; person-to-person contact |

| Scarlet fever | Streptococcus pyogenes | Pharynx, tongue | Direct contact with infected person; nasal droplets; fomites such as shared drinking glasses |

| Drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae disease (DRSP) | Streptococcus pneumoniae | Pharynx, lungs, alveoli | Person-to-person contact |

| Mycoplasmal pneumonia | Mycoplasma pneumoniae | Lungs; mucous membranes | Nasal secretions among people in crowded environments |

| Chlamydial pneumonia | Chlamydia pneumoniae | Lungs | Inhalation of respiratory droplets |

| Pertussis (whooping cough) | Bordetella pertussis | Trachea—ciliated epithelial cells | Inhalation of respiratory droplets |

| Tuberculosis | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Lungs | Inhalation of respiratory droplets |

| Staphylococcal pneumonia | Staphylococcus aureus; S. pneumoniae | Lungs | Nosocomial; complication after influenza |

| Haemophilus infections | Haemophilus influenzae | Pharynx, bronchi, lungs | Inhalation of respiratory droplets |

| Klebsiella pneumonia | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Lungs | Nosocomial |

| Diphtheria | Corynebacterium diphtheriae | Respiratory membranes | Inhalation of respiratory droplets |

| Legionellosis | Legionella pneumophila | Lungs | Inhalation of contaminated water mist |

| Psittacosis (“parrot fever”) | Chlamydia psittaci | Lungs | Inhalation of dried bird excrements or secretions |

| Inhalation anthrax | Bacillus anthracis | Lungs | Inhalation of spores |

| Q fever | Coxiella burnetii | Lungs | Inhalation of contaminated droplets excreted by infected animals |

Streptococcal Infections

The genus Streptococcus is composed of spherical gram-positive bacteria well known for being responsible for “strep throat,” but is also capable of causing meningitis, pneumonia, endocarditis, erysipelas, necrotizing fasciitis (see Chapter 10, Infections of the Integumentary System, Soft Tissue, and Muscle), and toxic shock syndrome. The virulence of group A Streptococcus seems to be increasing worldwide.

Scarlet Fever

Scarlet fever is an upper respiratory disease also caused by an infection with a group A β-hemolytic streptococcus (Streptococcus pyogenes) (Figure 11.2) and once was a serious childhood disease but now is generally treatable. The incubation period is 1 to 2 days and typically begins with a fever and sore throat, but might also exhibit chills, vomiting, abdominal pain, and malaise. The exotoxin produced by the bacteria is responsible for the “strawberry” tongue (Figure 11.3) as well as the characteristic fine rash on the chest, neck, groin, and thighs. The treatment of scarlet fever is the same antibiotic treatment as for strep throat, and complications with appropriate treatment are rare.

This micrograph shows a Gram stain of S. pyogenes, a gram-positive coccus that is usually arranged in chains. This bacterium is typically found in the oral cavity and throat. The organism is responsible for a variety of infections including strep throat, tonsillitis, and necrotizing fasciitis.

Streptococcus pneumoniae

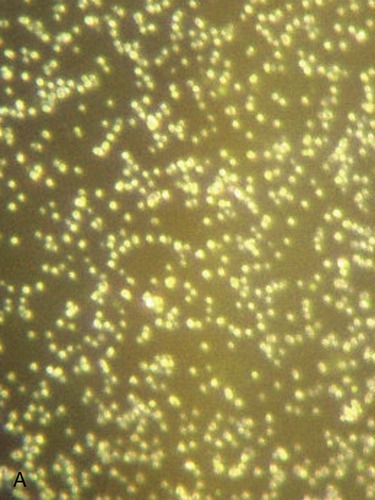

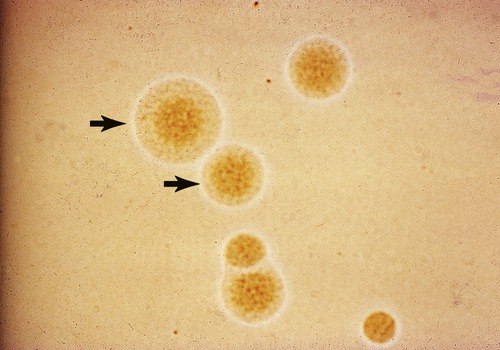

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a gram-positive, encapsulated α-hemolytic diplococcus (Figure 11.4), also known as pneumococcus, and is a common cause of mild respiratory illness, but also a major source of pneumonia. Other than pneumonia the organism is also capable of causing pharyngitis, sinusitis, otitis media, meningitis, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, endocarditis, peritonitis, pericarditis, cellulitis, and brain abscess. S. pneumoniae is a common inhabitant of the nasopharynx of healthy people, but can be the cause of disease when the organism reaches other areas such as the eustachian tubes, nasal sinuses, and lungs. Furthermore the organism can be found in larger numbers in environments where people spend a lot of time in close proximity and it can be transmitted by person-to-person contact or by inhalation. If the organism is inhaled and not removed by the ciliary escalator (such as in smokers, in whom the cilia have been damaged or degenerated), or the mucous membranes are damaged by a viral infection, the bacteria can attach or even penetrate the mucosa. Once the organism succeeds in getting to a site where it normally is not found it will stimulate the immune system of the host, resulting in the attraction of leukocytes (see Chapter 20, The Immune System). The capsule of S. pneumoniae is resistant to phagocytosis and if immunity is not present the alveolar macrophages are incapable of destroying pneumococci. In this case the bacterium spreads into the bloodstream, where it most likely causes bacteremia. The organism then can get to other areas of the body, causing the conditions mentioned earlier. The virulence of S. pneumoniae is a direct result of its capsule and the encapsulated (smooth) strains are the ones causing disease, whereas the nonencapsulated (rough) strains are avirulent.

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a gram-positive coccus; the cocci are usually arranged in pairs (diplococci). In a large percentage of the population this organism is part of the normal flora of the mouth and throat; however, it can cause pneumonia. A, Dark-field image showing the diplo, or paired, arrangement of many of the cells. B, Capsule stain illustrating the arrangements of the cells and the thick capsule surrounding them.

Other Common Infections

Mycoplasmal Pneumonia

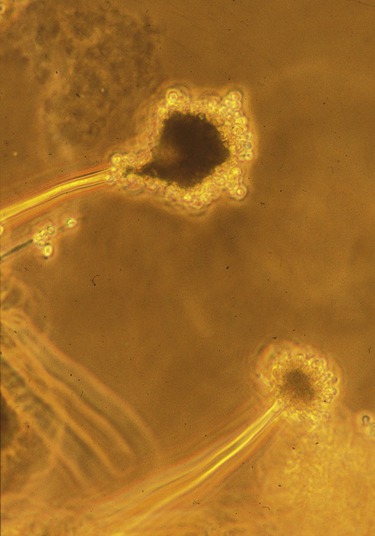

Mycoplasma pneumoniae, a small bacterium that lacks a cell wall (Figure 11.5), is the cause of primary atypical pneumonia, a relatively mild pneumonia, which usually affects people younger than 40 years of age. Transmission occurs by respiratory droplets through inhalation or person-to-person contact. The incubation period lasts 10 to 14 days and epidemics can occur, especially in crowded areas such as in schools, among military personnel, in homeless shelters, and within a family. Symptoms may last 1 to 3 weeks, starting with fatigue, a sore throat, and a dry cough. It resembles influenza at the beginning, followed by worsening of the cough, which eventually produces sputum. Although it is usually a mild condition and most people recover without treatment, severe cases require antibiotic treatment. It should be noted that because of the lack of a cell wall these organisms are resistant to penicillin and other β-lactam antibiotics (see Chapter 22, Antimicrobial Drugs), which act by interrupting the formation of peptidoglycan cross-links of bacterial cell walls.

Mycoplasma pneumoniae is a small bacterium that lacks a cell wall and is responsible for an estimated 2 million cases of pneumonia in the United States annually, including approximately 100,000 hospitalizations. (From Forbes BA, Sahm DF, Weissfeld AS: Bailey & Scott’s diagnostic microbiology, ed 12, St. Louis, 2007, Mosby.)

Pertussis (Whooping Cough)

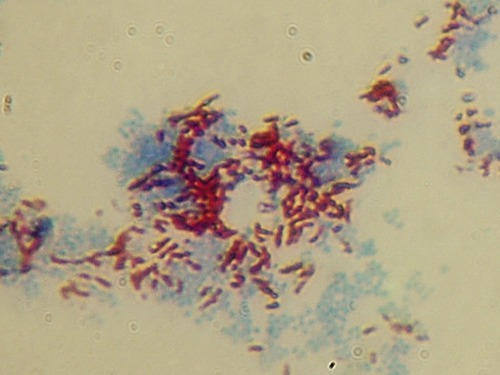

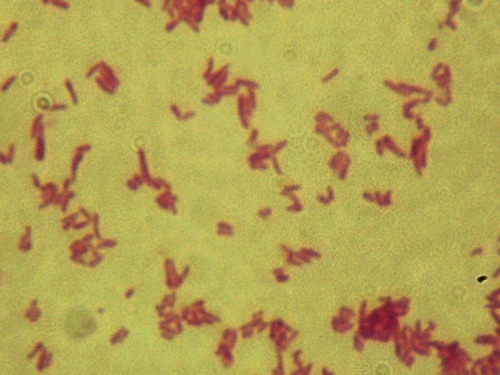

Pertussis, also known as whooping cough, is a highly contagious disease caused by Bordetella pertussis, an extremely small, aerobic, gram-negative coccobacillus (Figure 11.6). It is a serious disease that can cause permanent disability and even death. Pertussis is easily spread from person to person by airborne droplets discharged from the mucous membranes of infected people. Initial symptoms occur about a week after exposure and resemble those of the common cold. The severe coughing spells start approximately 10 to 12 days later and these spells may lead to vomiting. The coughing often ends with a “whoop” noise caused when the patient is trying to take a breath. Despite the availability of, and high coverage with vaccines, pertussis is one of the leading causes of vaccine-preventable deaths worldwide. Ninety percent of all cases occur in the underdeveloped countries and most deaths involve infants who are either not vaccinated or incompletely vaccinated. Treatment with effective antibiotics, if started early, shortens the infectious period but usually does not alter the outcome of the disease.

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is a deadly infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Figure 11.7). TB is transmitted through the air when an infected person coughs, sneezes, or even talks. Moreover, TB is no longer a disease of the past; it is still a leading killer of young adults worldwide. TB is a chronic condition that usually infects the lungs, but other parts of the body might be involved as well. Most people infected with the organism do not show symptoms, but have latent tuberculosis. According to the World Health Organization (WHO, Geneva, Switzerland) estimate, annually 8 million people worldwide will develop active TB with nearly 2 million deaths. The risk for development of the disease is higher in the first year after infection, but the disease still can occur much later.

This micrograph illustrates an acid-fast stain of Mycobacterium smegmatis, an organism with a similar morphology to M. tuberculosis, the causative agent of tuberculosis.

• The HIV/AIDS epidemics: People with HIV have an immunocompromised immune system and are more likely to develop active TB, even shortly after first infection.

• Increased numbers of foreign-born nationals who enter the United States from places that have a high incidence of TB cases: These places include Africa, Asia, and Latin America. More than half of the TB cases in the United States are among foreign-born nationals now living here.

• Failure of patients to complete the prescribed antibiotic treatment: These patients stay infectious longer and transmit the disease to more people. Furthermore, incomplete antibiotic treatment can contribute to antibiotic-resistant strains of M. tuberculosis.

• Increasing number of elderly in the United States: The increase in the aging population in the United States results in greater numbers residing in long-term facilities. Many of these elderly have declining health and may develop active TB from an infection they obtained much earlier in life.

Several new and better vaccines for the prevention of TB infection are being developed and have entered clinical trials in the United States. At present, health experts in the United States do not recommend the use of the vaccine for general use in this country because it makes the screening procedures for infected individuals more difficult. The TB skin test, also known as the tuberculin PPD test, is used for screening purposes and will show positive results in persons who currently has TB or were exposed or vaccinated in the past. The test is based on the fact that an encounter with M. tuberculosis produces a delayed hypersensitivity skin reaction (see Chapter 20, The Immune System) to certain components of the bacterium.

Rare and Opportunistic Infections

Staphylococcal Pneumonia

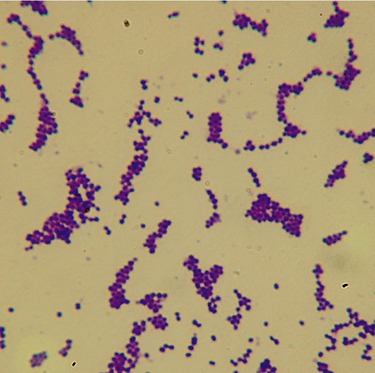

Respiratory infections due to staphylococci are relatively rare in the healthy adult but are common opportunistic organisms in compromised hosts in hospitals and other institutions, causing hospital-acquired and institution-acquired pneumonia. Staphylococcus aureus, a gram-positive coccus (Figure 11.8), causes only 2% of community-acquired pneumonias, but 10% to 15% of hospital-acquired pneumonias are due to this organism. These infections most likely occur in people who are hospitalized with another disease and often involves the very young, the old, and people with another debilitating illness. Although the illness is rare, it is serious and causes death in about 15% to 40% of the cases. Treatment is usually a type of penicillin; however, more strains of Staphylococcus are becoming resistant to these and the use of other antibiotics such as vancomycin may be required. Staphylococcal pneumonia also has been reported to be the cause of severe complications after the 2003–2004 influenza seasons.

Staphylococcus aureus is a gram-positive coccus arranged in grapelike clusters. This is a ubiquitous bacterium that can cause a variety of infections and diseases.

Haemophilus Infections

Many Haemophilus species are part of the normal flora in the upper airways of children and adults and most of them rarely cause disease. However, Haemophilus influenzae, a gram-negative coccobacillus (Figure 11.9), is a common cause of infection (bronchiolitis) in children and chronic bronchitis in adults, and occasionally meningitis.

Haemophilus influenzae is a gram-negative coccobacillus (pleomorphic) commonly found in the upper respiratory tract. The bacterium can cause pneumonia, epiglottitis, and meningitis. (From Murray PR, Rosenthal KS, Pfaller MA: Medical microbiology, ed 5, St. Louis, 2005, Mosby.)

Diphtheria

Diphtheria is caused by Corynebacterium diphtheriae, a facultative anaerobic, gram-positive bacillus (Figure 11.10), which attacks the throat and nose. It is an upper respiratory illness characterized by a sore throat, low-grade fever, and the formation of a pseudomembrane on the tonsils and pharynx. The formation of the pseudomembrane can cause life-threatening respiratory obstruction. It is a highly contagious disease easily spread by direct physical contact or aerosol secretions from an infected individual. Once the infection takes place the bacterium produces an exotoxin that can potentially spread via the bloodstream to other organs such as the heart and cause significant damage.

Corynebacterium diphtheriae is a gram-positive, nonsporing, rod-shaped to pleomorphic bacterium that causes diphtheria. Note the unique arrangement of the bacilli, which are often parallel along the long axis of the rods or in V- or W-shaped clumps, sometimes referred to as a “Chinese character” arrangement. This is due to a process called “snapping division,” by which reproducing cells divide along the long axis of the cells instead of the ends of the cells.

Legionellosis

Inhalation Anthrax

Anthrax is an acute infectious disease caused by Bacillus anthracis, a gram-positive, spore-forming, facultative anaerobe (Figure 11.11), commonly found in wild and domestic vertebrates. The disease is zoonotic and can occur in humans if a person is exposed to an infected animal, tissue from an infected animal, or spores of the bacterium. The infection can be attained through the skin, by inhalation, or ingestion. There is no known transmission of anthrax from person to person. Symptoms of the disease vary depending on how it was acquired. Symptoms commonly occur within 7 days, but can take up to 60 days. Inhaling the spores only means that a person has been exposed to the disease; it does not mean that symptoms automatically appear, because the bacterial spores must germinate before the actual disease occurs. Once the spores germinate, they release several toxins that cause internal bleeding, swelling, and tissue necrosis. Anthrax spores can remain viable in the environment for 50 years.

This micrograph represents a simple stain of B. anthracis, a gram-positive, spore-forming bacillus that can cause anthrax. The bacterium is part of the typical soil flora.

The initial symptoms of anthrax when the bacterial spores are acquired through inhalation are similar to those of a common cold, including fever, chills, sweating, fatigue, malaise, headache, cough, shortness of breath, and some chest pain. After several days the symptoms usually progress to the second stage with fever, severe breathing problems, and shock. Cutaneous anthrax appears as a large, deep lesion on the skin, and gastrointestinal anthrax causes lesions in the intestinal tract, often with intestinal bleeding. Antibiotic therapy administered after known or suspected exposure can help prevent the disease. Several antibiotics are effective against anthrax; however, if the second stage has been reached, inhalation anthrax is usually fatal. Vaccination has been developed and is available to select U.S. military personnel, but not to the general public. Anthrax spores and their use in bioterrorism are discussed in Chapter 24 (Microorganisms in the Environment and Environmental Safety).

Q Fever

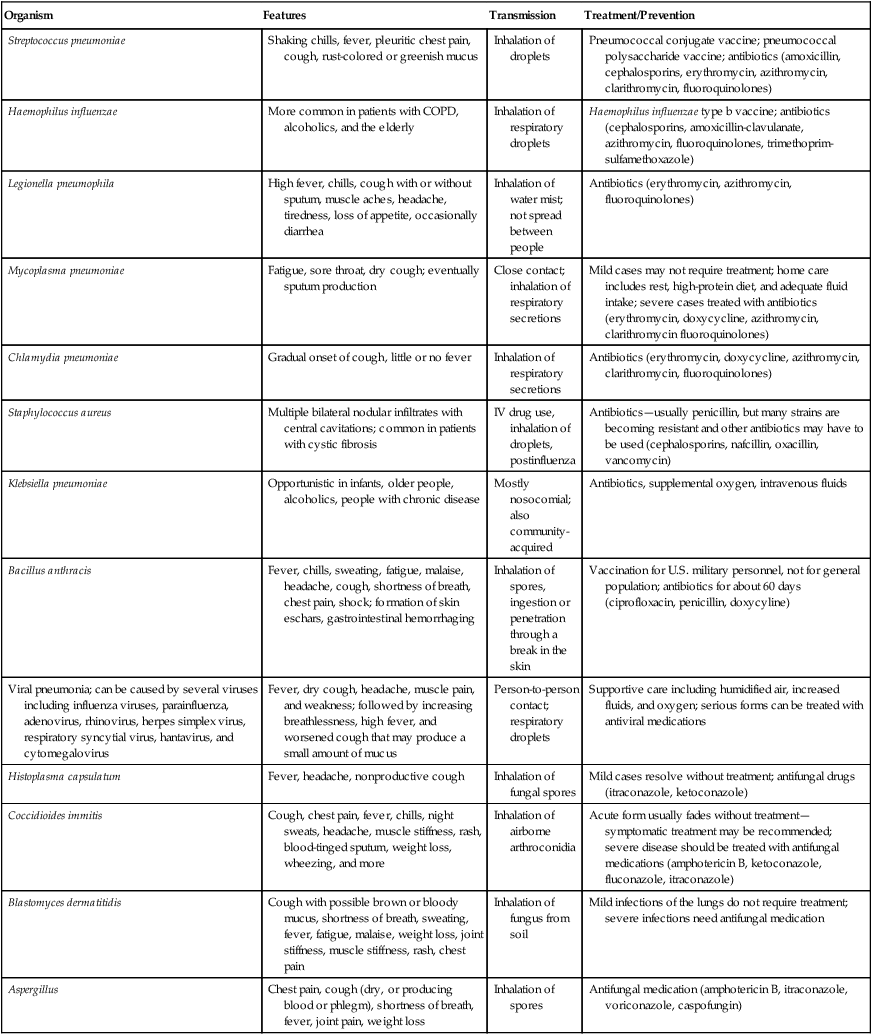

HEALTHCARE APPLICATION

Pneumonias

| Organism | Features | Transmission | Treatment/Prevention |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | Shaking chills, fever, pleuritic chest pain, cough, rust-colored or greenish mucus | Inhalation of droplets | Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine; pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine; antibiotics (amoxicillin, cephalosporins, erythromycin, azithromycin, clarithromycin, fluoroquinolones) |

| Haemophilus influenzae | More common in patients with COPD, alcoholics, and the elderly | Inhalation of respiratory droplets | Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine; antibiotics (cephalosporins, amoxicillin-clavulanate, azithromycin, fluoroquinolones, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole) |

| Legionella pneumophila | High fever, chills, cough with or without sputum, muscle aches, headache, tiredness, loss of appetite, occasionally diarrhea | Inhalation of water mist; not spread between people | Antibiotics (erythromycin, azithromycin, fluoroquinolones) |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | Fatigue, sore throat, dry cough; eventually sputum production | Close contact; inhalation of respiratory secretions | Mild cases may not require treatment; home care includes rest, high-protein diet, and adequate fluid intake; severe cases treated with antibiotics (erythromycin, doxycycline, azithromycin, clarithromycin fluoroquinolones) |

| Chlamydia pneumoniae | Gradual onset of cough, little or no fever | Inhalation of respiratory secretions | Antibiotics (erythromycin, doxycycline, azithromycin, clarithromycin, fluoroquinolones) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Multiple bilateral nodular infiltrates with central cavitations; common in patients with cystic fibrosis | IV drug use, inhalation of droplets, postinfluenza | Antibiotics—usually penicillin, but many strains are becoming resistant and other antibiotics may have to be used (cephalosporins, nafcillin, oxacillin, vancomycin) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Opportunistic in infants, older people, alcoholics, people with chronic disease | Mostly nosocomial; also community-acquired | Antibiotics, supplemental oxygen, intravenous fluids |

| Bacillus anthracis | Fever, chills, sweating, fatigue, malaise, headache, cough, shortness of breath, chest pain, shock; formation of skin eschars, gastrointestinal hemorrhaging | Inhalation of spores, ingestion or penetration through a break in the skin | Vaccination for U.S. military personnel, not for general population; antibiotics for about 60 days (ciprofloxacin, penicillin, doxycyline) |

| Viral pneumonia; can be caused by several viruses including influenza viruses, parainfluenza, adenovirus, rhinovirus, herpes simplex virus, respiratory syncytial virus, hantavirus, and cytomegalovirus | Fever, dry cough, headache, muscle pain, and weakness; followed by increasing breathlessness, high fever, and worsened cough that may produce a small amount of mucus | Person-to-person contact; respiratory droplets | Supportive care including humidified air, increased fluids, and oxygen; serious forms can be treated with antiviral medications |

| Histoplasma capsulatum | Fever, headache, nonproductive cough | Inhalation of fungal spores | Mild cases resolve without treatment; antifungal drugs (itraconazole, ketoconazole) |

| Coccidioides immitis | Cough, chest pain, fever, chills, night sweats, headache, muscle stiffness, rash, blood-tinged sputum, weight loss, wheezing, and more | Inhalation of airborne arthroconidia | Acute form usually fades without treatment—symptomatic treatment may be recommended; severe disease should be treated with antifungal medications (amphotericin B, ketoconazole, fluconazole, itraconazole) |

| Blastomyces dermatitidis | Cough with possible brown or bloody mucus, shortness of breath, sweating, fever, fatigue, malaise, weight loss, joint stiffness, muscle stiffness, rash, chest pain | Inhalation of fungus from soil | Mild infections of the lungs do not require treatment; severe infections need antifungal medication |

| Aspergillus | Chest pain, cough (dry, or producing blood or phlegm), shortness of breath, fever, joint pain, weight loss | Inhalation of spores | Antifungal medication (amphotericin B, itraconazole, voriconazole, caspofungin) |

COPD, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IV, intravenous.

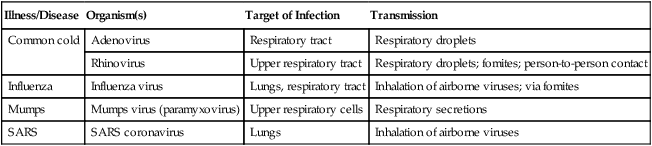

Viral Infections

Although many bacteria are part of the resident normal flora of the upper respiratory system, a large number of viruses are probably part of the transient flora of the nasopharyngeal cells as well. Not all infections of cells cause disease, and such infections might not be apparent because of the lack of symptoms. Moreover, most virions that are able to reach the lungs are destroyed by alveolar macrophages. Nevertheless, an estimated 90% of acute upper respiratory and approximately 50% of lower respiratory infections are caused by viruses (Table 11.2).

TABLE 11.2

Viral Infections Acquired Through the Respiratory Tract

| Illness/Disease | Organism(s) | Target of Infection | Transmission |

| Common cold | Adenovirus | Respiratory tract | Respiratory droplets |

| Rhinovirus | Upper respiratory tract | Respiratory droplets; fomites; person-to-person contact | |

| Influenza | Influenza virus | Lungs, respiratory tract | Inhalation of airborne viruses; via fomites |

| Mumps | Mumps virus (paramyxovirus) | Upper respiratory cells | Respiratory secretions |

| SARS | SARS coronavirus | Lungs | Inhalation of airborne viruses |

Influenza

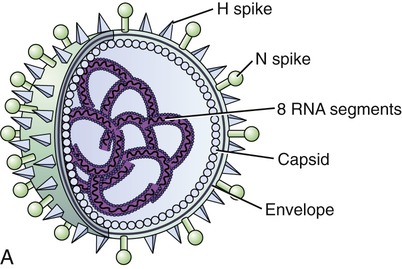

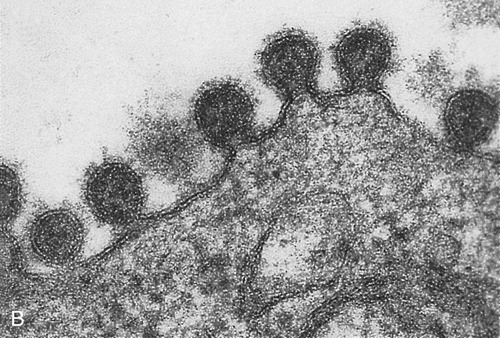

The influenza genome is not a single piece of nucleic acid, but instead consists of 8 pieces of segmented negative-sense RNA, encoding 11 proteins. Two of these proteins, hemagglutinin and neuraminidase, large glycoproteins, are well characterized and found on the outside of the viral particles (Figure 11.12, A and B). Neuraminidase is an enzyme involved in the release of the progeny viruses from infected cells. Hemagglutinin is a lectin that mediates the binding of the virus to target cells and the subsequent entry of the viral genome into the host. After the release of the newly produced influenza viruses the host cell dies.

Influenza viruses can be subdivided into different strains based on their antigenic characteristics (Box 11.1). New influenza virus variants are the result of frequent antigenic changes (i.e., antigenic drift) resulting from point mutations during viral replication. These rapid mutations are partially due to the absence of RNA-proofreading enzymes. As a result, RNA-dependent RNA transcriptase makes a single-nucleotide insertion error about once every 10,000 nucleotides, making almost every newly formed influenza virus a potential mutant. The influenza B viruses undergo antigenic drift less frequently than the influenza A viruses.

• Gastrointestinal symptoms: Nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea can occur and are more common in children than in adults

Epidemics of influenza in the United States typically appear during the winter months, causing disease among all age groups. Every year millions of Americans are infected and an estimated 36,000 Americans die of influenza-related illness. Especially vulnerable are people with a weak immune system such as the very young, the elderly, and those with a compromised immune system as a result of cancer therapy or disease. Influenza vaccination, that is, the annual “flu shot,” is the primary method for preventing the flu and its possible complications. Vaccination can prevent hospitalization and death among people at risk, but also will reduce flu-associated respiratory illnesses among people of all age groups. According to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), a part of the CDC, annual influenza vaccinations are recommended for people at high risk for influenza-related complications, and persons who live with or care for persons at high risk (Box 11.2).

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)

SARS is a respiratory illness caused by the SARS coronavirus. The original outbreak (November 2002) seems to have originated in mainland China. The disease spread worldwide over several months before the outbreak was curtailed with help from and coordination by the WHO. This first global outbreak of SARS was reported to have a mortality rate of 9.6% between 2002 and 2003 (see Health Care Application: Global SARS Outbreak).

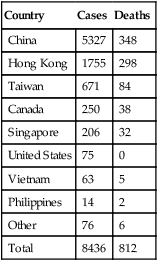

HEALTHCARE APPLICATION

Global SARS Outbreak (November 2002–July 2003)*

| Country | Cases | Deaths |

| China | 5327 | 348 |

| Hong Kong | 1755 | 298 |

| Taiwan | 671 | 84 |

| Canada | 250 | 38 |

| Singapore | 206 | 32 |

| United States | 75 | 0 |

| Vietnam | 63 | 5 |

| Philippines | 14 | 2 |

| Other | 76 | 6 |

| Total | 8436 | 812 |

*Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (http://www.who.int/csr/sars/country/2003_07_09/en/)

Fungal Infections

Fungi can cause infections of the skin, hair, nails and also of the respiratory system. Respiratory diseases caused by fungi most commonly involve the lungs and are referred to as deep mycoses. These diseases include histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis, blastomycosis, and aspergillosis (Table 11.3). Dimorphism in some fungi (see Fungi in Chapter 8, Eukaryotic Microorganisms) can aid in infection as the single-celled yeast can more easily spread throughout the body via the bloodstream.

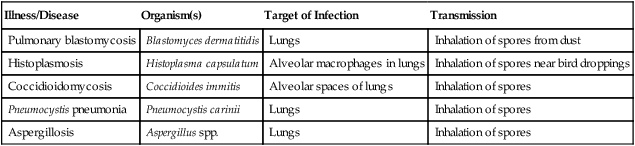

TABLE 11.3

Fungal Infections Acquired Through the Respiratory Tract

| Illness/Disease | Organism(s) | Target of Infection | Transmission |

| Pulmonary blastomycosis | Blastomyces dermatitidis | Lungs | Inhalation of spores from dust |

| Histoplasmosis | Histoplasma capsulatum | Alveolar macrophages in lungs | Inhalation of spores near bird droppings |

| Coccidioidomycosis | Coccidioides immitis | Alveolar spaces of lungs | Inhalation of spores |

| Pneumocystis pneumonia | Pneumocystis carinii | Lungs | Inhalation of spores |

| Aspergillosis | Aspergillus spp. | Lungs | Inhalation of spores |

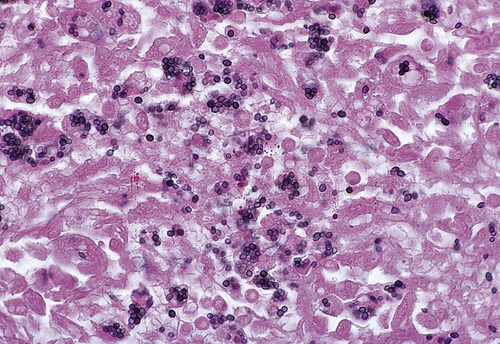

Histoplasmosis

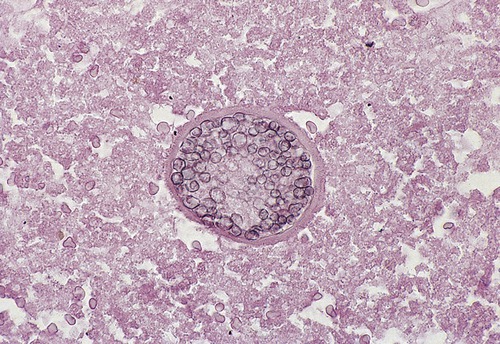

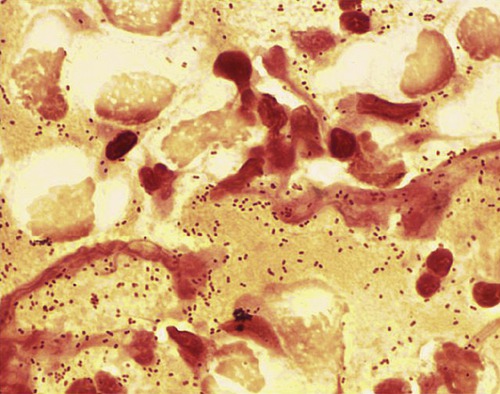

Histoplasma capsulatum (Figure 11.13) infections are generally acute respiratory infections that occur in all age groups and in both sexes. The disease affects primarily the lungs and occasionally other organs. The infections are more frequent in adult males, probably because of more frequent occupational exposure. Transmission occurs by inhalation of airborne conidia of the fungus (see Chapter 8). Reservoirs of the organism can be found in soil around old chicken houses, starling bird roosts, and bat caves.

This is a micrograph of H. capsulatum, a fungus whose yeast cell stage causes the disease histoplasmosis. (From Forbes BA, Sahm DF, Weissfeld AS: Bailey & Scott’s diagnostic microbiology, ed 12, St. Louis, 2007, Mosby.)

• Avoid areas that may be reservoirs of the fungus, such as areas of accumulating bird guano.

• Persons having to work in areas where there is a risk of exposure to H. capsulatum should consult the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH, Washington, DC) document “Histoplasmosis: Protecting Workers at Risk” (available at http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2005-109/). This particular document contains information about work practices and personal protective equipment designed to reduce the risk of infection.

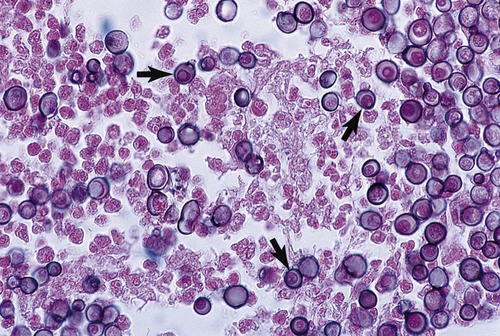

Coccidioidomycosis

The causative agent of coccidioidomycosis is Coccidioides immitis (Figure 11.14), which resides in the soil of certain parts of the southwestern United States (Arizona, California, Nevada, New Mexico, and Texas), parts of Mexico, and areas in South America. Reservoirs include desert soil, rodent burrows, archaeological remains, and mines. Transmission occurs by inhalation of airborne arthroconidia. Exposure often occurs after natural disasters such as dust storms and earthquakes, potentially exposing thousands of people. This type of exposure is also possible after disturbance of soil by humans. Dust that covers material from endemic areas can also serve as the vehicle of infection; these materials include but are not limited to Native American pots, blankets, and other items sold to tourists, especially in recreational areas.

Blastomycosis

Blastomycosis is an acute or chronic infection caused by the pathogen Blastomyces dermatitidis (Figure 11.15). Spores of the fungus generally enter the body by inhalation to affect primarily the lungs, but occasionally spread via the bloodstream to other areas of the body, including the skin. The reservoirs for Blastomyces dermatitidis are primarily wood and soil. Blastomycosis is considered a rare infection and occurs primarily in the south–central and Midwestern United States and Canada. In addition, infections have also been observed in widely scattered areas of Africa. The disease often affects people with a compromised immune system, such as patients receiving transplants and patients undergoing chemotherapy.

This is a micrograph of B. dermatitidis, a dimorphic fungus whose yeast cell stage can cause blastomycosis, a systemic fungal infection. (From Forbes BA, Sahm DF, Weissfeld AS: Bailey & Scott’s diagnostic microbiology, ed 12, St. Louis, 2007, Mosby.)

• A flulike condition with fever, chills, myalgias, headache, and a nonproductive cough that resolves itself within days

• An acute illness with symptoms similar to those of bacterial pneumonia, including high fever, chills, a productive cough (brown or bloody mucus), and pleuritic chest pain

• A chronic illness resembling tuberculosis or lung cancer. The symptoms include low-grade fever, a productive cough, night sweats, and weight loss

• A speedy, progressive, and severe disease that causes acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), a life-threatening condition that causes lung swelling and fluid buildup in the air sacs. This condition is a medical emergency, because the fluid inhibits gas exchange and therefore the passage of oxygen from the air into the bloodstream is compromised.

Pulmonary Aspergillosis

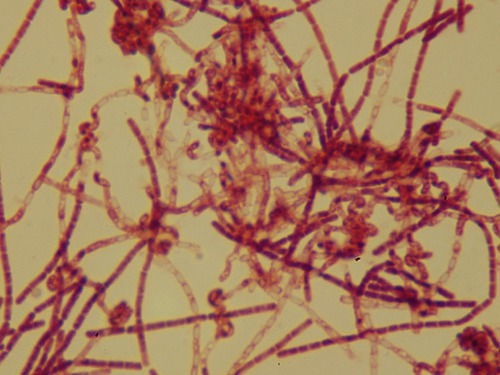

Pulmonary aspergillosis is caused by one or more species of Aspergillus (Figure 11.16), a mold commonly found in decaying plants, stored hay, compost piles, bird droppings, and any site where excess dust accumulates. Given the appropriate conditions, the organism forms large amounts of spores that are ultimately released into the environment, where they may remain suspended for long periods of time. Aspergillus spp. can also be found in the hospital environment, including showerheads, hospital water storage tanks, and potted plants. Aspergillus conidia (spores) are small, can easily be transmitted by inhalation, and subsequently may colonize in the upper or lower respiratory tracts. The respiratory tract is the most frequent and most important portal of entry for this fungus. At present there is no evidence of person-to-person transmission. Pulmonary aspergillosis has been subdivided into four major forms:

This is a micrograph of Aspergillus, an opportunistic fungal pathogen that can cause a variety of diseases collectively called aspergillosis.

• Formation of a “fungus ball” (aspergilloma) within preexisting cavities that have developed in areas of previous lung disease such as tuberculosis or lung abscess

• Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA), characterized by inflammation of the bronchi and/or alveoli. This condition may be similar to asthma or pneumonia, and many patients with ABPA also have asthma. Asthmatic patients and people with cystic fibrosis represent the highest at-risk group for allergic aspergillosis

• Secondary pulmonary (invasive) aspergillosis as an opportunistic systemic infection in immunocompromised patients. This is a serious infection with pneumonia and can spread to other parts of the body

Summary

• Structurally and functionally the respiratory system can be divided into the upper respiratory tract including the nose, pharynx and associated structures, and the lower respiratory system consisting of the larynx, trachea, bronchi, and lungs.

• The upper respiratory tract is colonized by normal flora commonly represented by Staphylococcus aureus and S. epidermidis, but other organisms also might be part of the normal flora, typically in much lower numbers.

• Bacterial infections of the respiratory tract can be caused by Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Klebsiella, Haemophilus, Bordetella, Corynebacterium, Mycobacterium, Legionella, Mycoplasma, Chlamydia, and Coxiella.

• Bacterial infections caused by the normal flora are generally secondary infections commonly occurring after damage to the mucosal lining due to viral infections such as the common cold.

• Other opportunistic infections involve bacteria that normally do not cause infection in the healthy adult, but are common in people with a compromised immune system.

• Rare and opportunistic bacterial infections include staphylococcal pneumonia, Haemophilus infections, Klebsiella pneumonia, diphtheria, legionellosis, psittacosis, inhalation anthrax, and Q fever.

• Many different viruses are frequent intruders of the nasopharynx and are responsible for the common cold, a normally self-limiting infection, and the most frequent of all human diseases.

• Primary causes for epidemics and endemic diseases of the respiratory system are the influenza viruses, which are capable of rapid mutations. Epidemics in the United States usually occur during the winter months, causing disease among all age groups, and can be potentially dangerous for the very young, the old, people with chronic diseases, and immunocompromised persons.

• In addition to the common cold and influenza, viral pneumonia, hantavirus pulmonary syndrome, and SARS are viral infections transmitted via the respiratory system.

• Respiratory diseases caused by fungi most commonly involve the lungs. They are referred to as deep mycoses, and include histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis, blastomycosis, and aspergillosis.

Review Questions

1. All of the following are structures of the lower respiratory system except:

2. Scarlet fever is caused by:

3. Which of the following organisms is commonly found in the normal flora of the upper respiratory system?

4. Whooping cough is caused by:

5. Which of the following cannot be and should not be treated with antibiotics?

6. Tuberculosis cannot be transmitted by:

7. The most virulent pathogen of the human flu virus is type:

8. SARS is a respiratory illness caused by:

9. Which of the following geographic areas contains reservoirs for Coccidioides immitis?

10. The formation of a “fungus ball” within preexisting cavities is a common development in:

11. Streptococcus pneumoniae is a gram-__________ bacterium.

12. Rheumatic fever is a rare complication of __________.

13. Parrot fever is caused by __________.

14. Legionellosis affects mainly the __________.

15. Hantaviruses, which can cause disease in humans, are carried by __________.

16. Describe the different types of respiratory infections caused by streptococcal species.

17. Discuss the reemergence of tuberculosis and MDR-TB.

18. Name the two distinct forms of legionellosis.

19. Discuss organisms that enter the human body via the respiratory tract and that can be a potential bioterrorism threat.