Infections of the Gastrointestinal System

After reading this chapter, the student will be able to:

• Identify the normal flora for each part of the gastrointestinal tract

• Describe the common infections that can occur in the oral cavity

• Describe gastroenteritis: its symptoms and possible causes

• Explain the difference between bacterial infections and bacterial intoxication

• Describe the causes, symptoms, transmission, prevention, and possible treatments of peptic ulcer, salmonellosis, typhoid fever, shigellosis, campylobacteriosis, and yersiniosis

• Identify and differentiate between the different types of Escherichia coli gastroenteritis

• Describe the causes, transmission, prevention, and possible treatments of botulism, staphylococcal intoxication, bacillus intoxication, and cholera

• Name the organisms responsible for most common outbreaks of viral gastroenteritis, and discuss prevention and treatments

• Discuss the mycoses that can affect the gastrointestinal system in both healthy and immunocompromised persons

• Describe the parasitic infections that are common in the United States, and describe those that are limited primarily to underdeveloped countries

Introduction

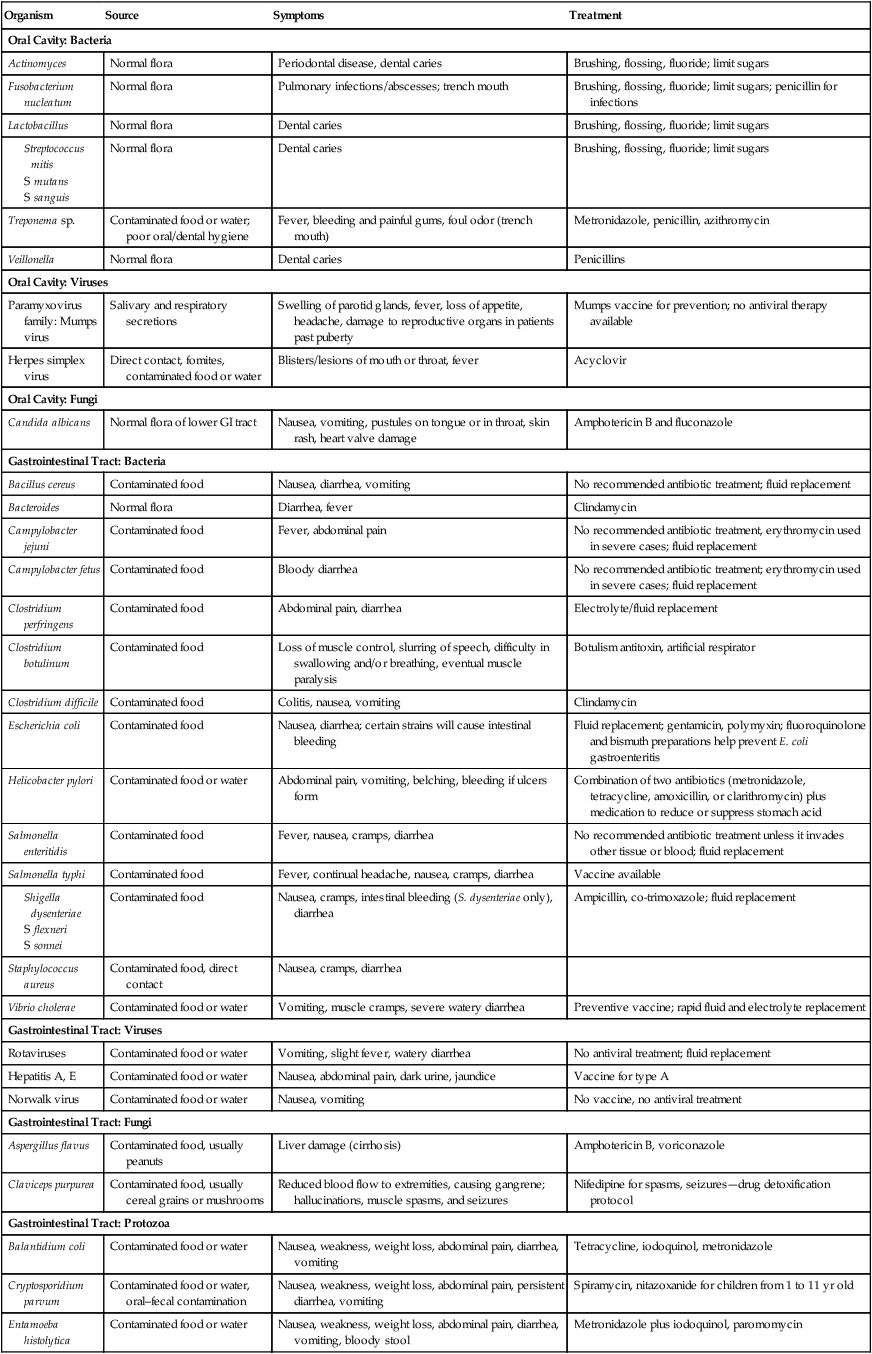

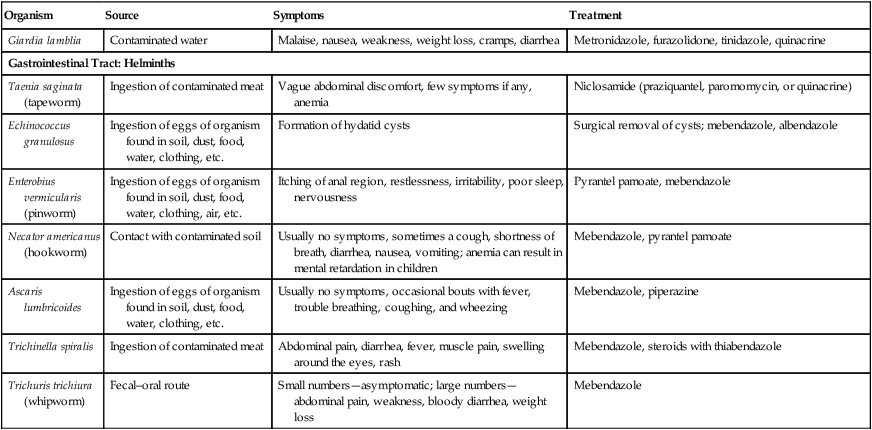

The gastrointestinal (GI) tract is a common and easily accessible portal of entry for microbes or their toxins, with the ability to cause infection, inflammation, and/or disease. Foodborne diseases are a major concern worldwide. Contaminated food, water, and fomites, if they gain access through the fecal–oral route, all are capable of infecting the gastrointestinal system. Moreover, microbial infections and diseases of the gastrointestinal tract are the second most common cause of illnesses in the United States, with respiratory illnesses being the most common. A summary of organisms causing disease of the digestive system is provided in Table 12.1.

TABLE 12.1

Summary of Disease-causing Organisms in the Digestive System

| Organism | Source | Symptoms | Treatment |

| Oral Cavity: Bacteria | |||

| Actinomyces | Normal flora | Periodontal disease, dental caries | Brushing, flossing, fluoride; limit sugars |

| Fusobacterium nucleatum | Normal flora | Pulmonary infections/abscesses; trench mouth | Brushing, flossing, fluoride; limit sugars; penicillin for infections |

| Lactobacillus | Normal flora | Dental caries | Brushing, flossing, fluoride; limit sugars |

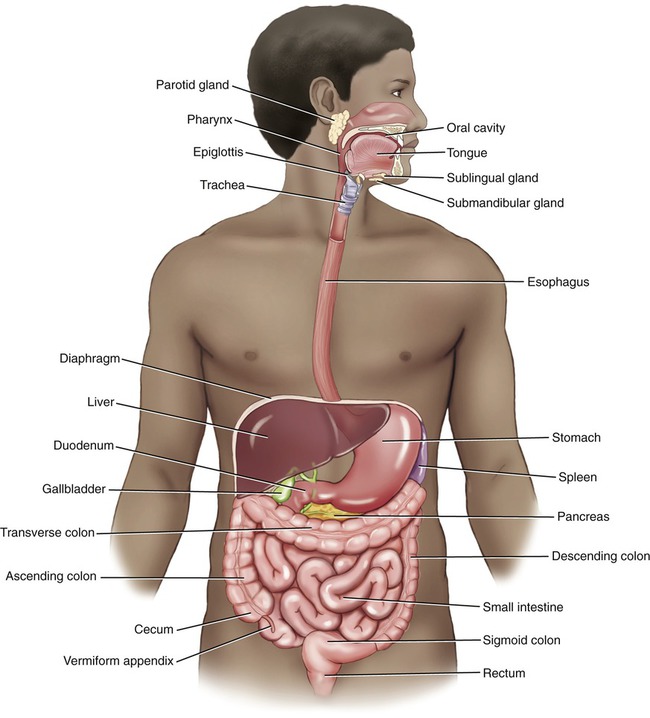

The GI tract, also referred to as the digestive tract, is a tubelike structure starting at the oral cavity (mouth); proceeding to the pharynx, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and large intestine; and terminating at the anus (Box 12.1). Together with its accessory organs, the biological function of the digestive system (Figure 12.1) is to digest and absorb nutrients for all cells of the body, to enable them to function.

The digestive system consists of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and its accessory organs. The GI tract includes the mouth, pharynx, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine, anal canal, and anus. The accessory organs are the teeth, tongue, salivary glands, liver, gallbladder, and pancreas.

The lining of the GI tract is a mucosal lining, and like the skin it acts as the first line of defense against microbes (see Chapter 20, The Immune System). However, it does not have a dead layer of cells as the skin does and therefore it is not as efficient a defense mechanism. On the other hand, it does provide a moist and warm environment, perfect for microbial growth. As with other portals of entry, the GI tract has a normal flora that also helps to protect against pathogens via competition.

Resident Microbial Flora

Stomach

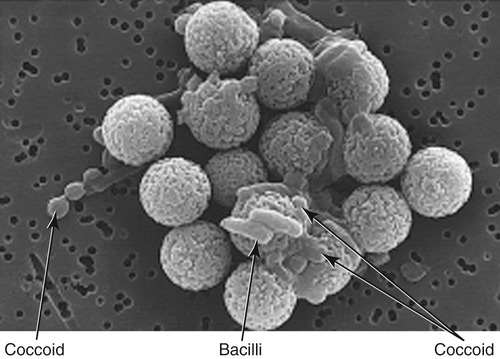

One organism that has been discovered to live in the human stomach is Helicobacter pylori, a gram-negative, microaerophilic, spiral-shaped bacterium (Figure 12.2). The organism is highly motile due to its flagella and moves through the stomach lumen until it burrows into the stomach’s mucosa to a depth where the pH is essentially neutral. It is estimated that about 30% to 50% of the earth’s population is colonized by H. pylori. Although colonization of the bacterium in the stomach is not necessarily a problem, H. pylori is the cause of most cases of gastritis and peptic ulcers (see Bacterial Infections later in this chapter).

Scanning electron micrograph of Helicobacter pylori, a gram-negative bacterium that is the most common cause of gastritis and peptic ulcers. Bacillus and coccoid forms of the organism are shown attached to large beads. (From Murray PR, Rosenthal KS, Pfaller MA: Medical microbiology, ed 5, St. Louis, 2005, Mosby.)

Dental Caries

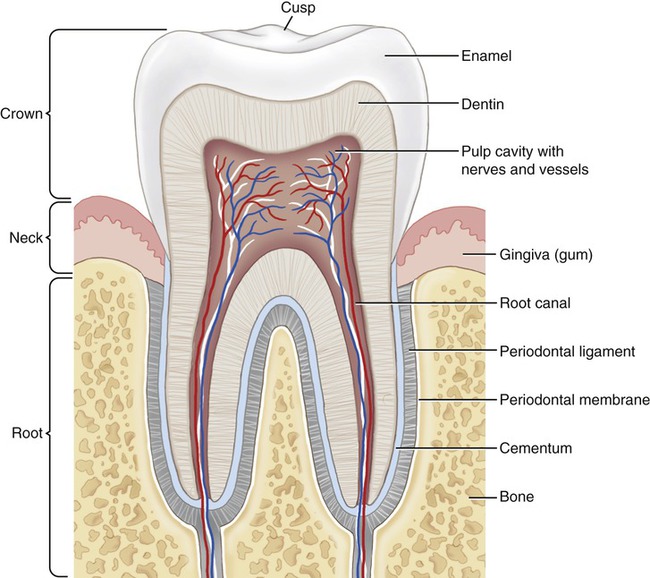

The oral cavity provides a good environment for a variety of microorganisms to flourish. Teeth, the tongue, and the salivary glands are accessory organs of digestion in this area. Microbial life on teeth was first observed by van Leeuwenhoek (see Chapter 1, Scope of Microbiology), who noticed that even after washing his teeth with vinegar, only microbes on the outer layer were killed, not those in the deeper layers.

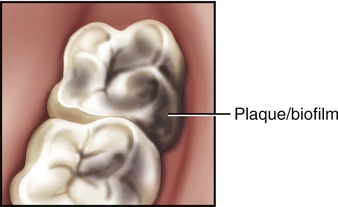

The enameled surface of the teeth (Figure 12.3) is hard and does not shed cells, which allows microorganism to attach and form a biofilm known as dental plaque. If not removed on a regular basis it can lead to cavities (caries) or other periodontal problems such as gingivitis (inflammation of the gums). The microorganisms responsible for the formation of dental plaque (Figure 12.4) are almost entirely bacteria, normally present in the oral cavity. Under usual circumstances, these bacteria (e.g., fusobacteria and actinomycetes) do not cause damage; however, failure to remove these biofilms by regular brushing of the teeth will cause the organisms closest to the tooth surface to change to anaerobic respiration. Anaerobic respiration of bacteria converts sucrose and other carbohydrates into lactic acid, which consequently leads to the demineralization of the adjacent tooth surface, resulting in dental caries.

Periodontal Disease

• Smoking/tobacco use has been shown to be one of the most significant risk factors in the development and progression of periodontal disease.

• Genetic predisposition to periodontal disease has been suggested by several studies and reported by the American Academy of Periodontology.

• Pregnancy, puberty, stress, medications, diabetes, grinding one’s teeth, poor nutrition, and other systemic diseases also have been implicated in the development of periodontal diseases.

Bacterial Infections/Illnesses

Bacteria are the most common cause of foodborne illness, which can be caused by the bacteria themselves, their toxins, or both. A bacterial infection occurs when a pathogen enters the GI tract, adheres, and multiplies (see Chapter 9, Infection and Disease). A bacterial intoxication occurs when toxins produced by bacteria contaminate food or water and then are introduced to the human body.

Bacterial Infections

Salmonellosis

• Avoiding raw or undercooked eggs, poultry, or meat

• Careful monitoring of homemade foods that include raw eggs (e.g., hollandaise sauce, salad dressings, ice cream, mayonnaise, cookie dough, and frostings)

• No consumption of nonpasteurized dairy products

• Avoidance of any chance of cross-contamination between raw and cooked foods

• Separation of uncooked meats from produce, cooked foods, and ready-to-eat foods

• Appropriate washing of hands, cutting boards, countertops, knives, and other utensils after handling uncooked foods

• Washing of hands before and after handling food

• Hand washing after handling reptiles or birds, or after contact with pet feces

Typhoid Fever

Typhoid fever is an acute, life-threatening illness caused by the most virulent serotype of Salmonella enterica, serotype Typhi, a rod-shaped, flagellated, gram-negative bacterium. Typhoid fever is transmitted through contaminated food or water, or through close contact with an infected person; it is not found in animals, and is transmitted only via human feces. Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi lives only in humans and persons with typhoid fever carry the bacteria in their bloodstream and intestinal tract. Some people exposed to and infected by the organism do not develop the disease, or might have a minor illness and subsequently recover and thus only be carriers of the disease (see Medical Highlights: Asymptomatic Disease Carriers: Typhoid Mary). Typhoid fever is more common in areas of the world where hand washing is not common, and where water is contaminated with human waste.

Escherichia spp. Gastroenteritis

• Enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) is the cause of diarrhea in infants and travelers in underdeveloped countries or areas where sanitation is poor. It is generally acquired by ingestion of contaminated food and water and the organism colonizes the small intestine. The illness can vary from minor discomfort to severe, cholera-like symptoms. The enterotoxins produced are heat-labile (LT) and/or heat-stable (ST) toxins.

• Enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC) penetrates and multiplies in the epithelial cells of the colon, resulting in destruction of these cells. The clinical symptoms are similar to those of Shigella dysentery (dysentery-like diarrhea) with fever. EIEC is an invasive organism but does not produce LT or ST toxins.

• Enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) is similar to EIEC and also does not produce LT or ST toxins, although it has been reported that the organism produces an enterotoxin similar to that of Shigella.

• Enteroaggregative E. coli (EAggEC) is accompanied by persistent diarrhea in young children. In addition to its toxin (enteroaggregative ST-like toxin) it also produces a hemolysin related to one made by strains of E. coli that commonly cause urinary tract infections.

• Enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) is currently represented by a single strain, the serotype O157:H7. This serotype produces large quantities of one or more related potent toxins, capable of producing severe damage to the intestinal lining. These toxins are closely related to the toxin produced by Shigella dysenteriae and cause diarrhea with abundant bloody discharge. It is frequently life-threatening because of its toxic effects on the kidneys (hemolytic uremia).

Listeriosis

Listeriosis is an illness caused by the microorganism Listeria monocytogenes. This gram-positive, nonsporing rod is a facultatively anaerobic intracellular pathogen that is acquired by ingesting contaminated food. The organism can spread to the bloodstream and the central nervous system (see Chapter 13, Infections of the Nervous System and Senses). It has the capacity to infect a variety of cells, and because it can spread to the circulatory system it is capable of causing infections in a number of different body systems.

After consuming Listeria-contaminated food, symptoms of the infection appear anywhere from 11 to 70 days later. Symptoms include fever, muscle aches, and sometimes gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea or diarrhea. If the infection reaches the nervous system headache, stiff neck, confusion, loss of balance, or convulsions may occur (see Chapter 13, Infections of the Nervous System and Senses). Listeriosis is treated with antibiotics; the duration of treatment depends on the host and the symptoms of the illness.

Bacterial Intoxications

Botulism

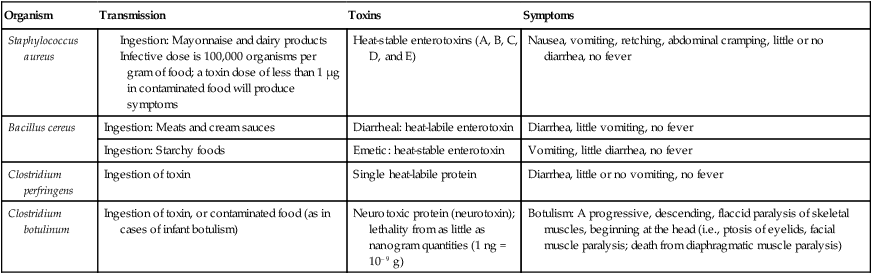

Botulism (see also Chapter 21, Pharmacology) is a rare disease in the United States and healthcare providers report an average of 110 cases per year. Although rare, this mostly foodborne illness can be fatal if not treated quickly. Four forms of botulism have been identified: (1) classic or foodborne botulism, (2) infant botulism, (3) wound botulism, and (4) inhalation botulism. The illness is caused by the toxin produced by Clostridium botulinum, an anaerobic organism that flourishes in sealed containers, and is commonly isolated from soil and water samples throughout the world. The organism produces a neurotoxin most commonly acquired by a patient through consumption of contaminated food. Foodborne botulism often can be blamed on home-canned food with low acid content, such as asparagus, green beans, beets, and corn. However, baked potatoes wrapped in aluminum foil but not kept hot have also been blamed for outbreaks. Exposure to the toxin in an aerosolized form can quickly be fatal and is a concern in the defense against its use as a bioweapon (see Bioterrorism in Chapter 24, Microorganisms in the Environment and Environmental Safety).

HEALTHCARE APPLICATION

Organisms Responsible for Food Poisoning

| Organism | Transmission | Toxins | Symptoms |

| Staphylococcus aureus |

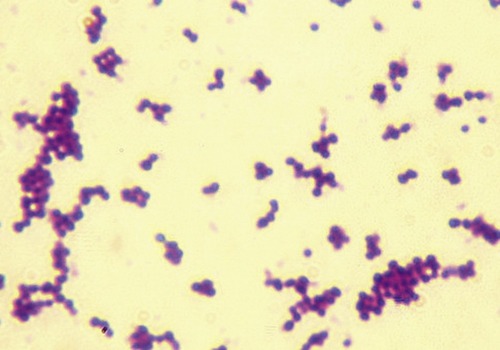

Staphylococcal Intoxication

Any food prepared and not appropriately chilled or refrigerated after preparation is a potential source of food poisoning. Staphylococcus aureus is one of the leading causes of gastroenteritis as a result of contaminated food ingestion, with the illness being caused by the absorption of staphylococcal enterotoxins present in the food. Staphylococcus aureus does not form endospores, as do C. perfringens, C. botulinum, and B. cereus. Staphylococcus is somewhat heat resistant and even the vegetative organism can tolerate 60° C for up to half an hour. The organism also has high resistance to osmotic changes, allowing it to grow in environments in which other bacteria cannot survive, such as high salt concentrations. S. aureus is often present in the normal flora of the nasal cavity; it can also survive on the skin, can be transmitted by hands into food, and, because of its resistance to environmental changes, thrives to produce disease-causing toxins (Figure 12.5). Normally, the infective dose (see Chapter 21, Pharmacology) is reached when the population of S. aureus exceeds 100,000 bacteria per gram of food.

Bacillus Intoxication

• The diarrheal type of the illness is characterized by abdominal pain and watery diarrhea, starting between 4 and 16 hours after a meal. The symptoms last for 12 to 24 hours. Although nausea may occur, vomiting is extremely rare with this type of intoxication. The enterotoxin associated with this illness is heat and acid labile; it can be inactivated at 56° C in 5 minutes.

• The emetic illness occurs 30 minutes to 6 hours after eating contaminated food as a result of ingestion of preformed toxins, and is characterized by an acute attack of nausea and vomiting. In general, the symptoms persist less than 24 hours. Because of the rapid onset of symptoms, this type of food poisoning is diagnosed quickly, especially with additional evidence of contamination in the food. The toxin associated with the emetic type of illness is a highly heat-stable toxin capable of surviving high temperatures (90 min at 126° C), exposure to trypsin, pepsin, and extreme pH (2–11) changes.

Viral Infections

Hepatitis

• Hepatitis A, caused by the hepatitis A virus (HAV), can affect anyone and in the United States; infections can be isolated or widespread. Good personal hygiene and appropriate sanitation will curb the spread of the disease. Vaccines are available for long-term prevention among people 12 months of age and older.

• Hepatitis E is rare in the United States. It is caused by the hepatitis E virus (HEV), and is transmitted in the same way as hepatitis A.

Fungal Infections

Candidiasis

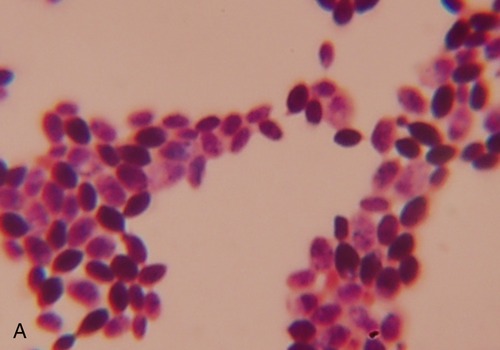

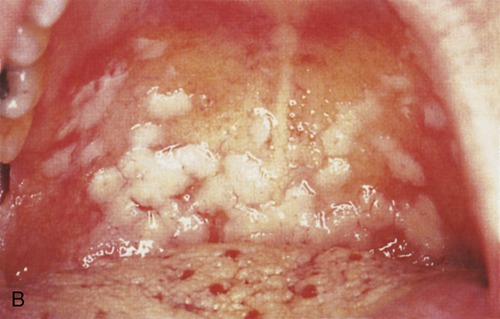

Candidiasis is an infection caused by a variety of opportunistic organisms of the genus Candida. Candida albicans is part of the normal gastrointestinal flora of about 80% of the human population, and does not usually cause any problems. Only the overgrowth of Candida due to changes in the normal environment will cause candidiasis, which can occur in many different body systems. Oral candidiasis, called “thrush,” is rare in healthy individuals, occurring in about 5% of newborns and 10% of the elderly, but is common in immunocompromised patients. Thrush presents itself as creamy white or bluish-white patches on the tongue, on the lining of the mouth, and/or in the throat (Figure 12.6). Certain medications such as antibiotics, corticosteroids, and the birth control pill may upset the normal flora of the mouth and allow Candida to overgrow. Certain medical conditions such as uncontrolled diabetes, HIV infection, cancer, dry mouth, or pregnancy may also provide a favorable condition for the development of candidiasis. Several antifungal preparations are available for the treatment of this condition (see Chapter 22, Antimicrobial Drugs).

A, Micrograph of the fungus Candida albicans in the yeast form (this fungus can also form filamentous mycelia) that is responsible for an oral infection called thrush. C. albicans can also cause vaginal infections in women. B, Thrush or oral candidiasis results in creamy white or bluish-white patches on the tongue, on the lining of the mouth, and/or in the throat. (B, Courtesy of J.A. Innes. From Mims C, Dockrell HM, Goering RV, et al: Medical microbiology, ed 3, St. Louis, 2004, Mosby.)

Aspergillosis

Aspergillus spp. can be opportunistic pathogens in almost all tissues of the body. They are mainly responsible for three distinct pulmonary diseases (see Chapter 11, Infections of the Respiratory System), but the systemic illness can produce abscesses in the gastrointestinal tract, especially in patients with AIDS.

Ergotism

The fungus Claviceps purpurea contaminates rye and wheat and produces substances called alkaloids. Ergotism is a result of ingestion of alkaloids (ergotamines) produced by the fungus. In excess, ergotamines can cause symptoms of hallucinations, severe gastrointestinal upset, a type of dry gangrene, and a painful burning sensation in the limbs and extremities that is called “St. Anthony’s fire.” Because of the effect of alkaloids on the central nervous system, ergotism is discussed in more detail in Chapter 13 (Infections of the Nervous System and Senses).

Parasitic Infections

Protozoans

Protozoans are unicellular eukaryotes (see Chapter 8, Eukaryotic Microorganisms) found in a wide range of habitats; most are free living and not harmful to humans. However, some are parasites and capable of causing debilitating and deadly diseases. They enter the human body either as a trophozoite, the active feeding and reproductive stage, or as a cyst, the dormant stage, becoming active under the appropriate environmental conditions.

Giardia intestinalis (Giardiasis)

Giardiasis is a common waterborne gastrointestinal disease in the United States, with the infective agents present in both drinking and recreational water. The causative agent is Giardia lamblia, also known as G. intestinalis, an organism that lives in the intestinal tracts of animals and humans worldwide. Once a human or other animal has been infected, the parasite will reside in the intestine and will pass into the feces (see Chapter 8, Eukaryotic Microorganisms). Therefore, Giardia is found in soil, food, water, or any surfaces that have been contaminated with infected feces. The symptoms of Giardia infection include diarrhea, flatulence, greasy stools, stomach cramps, and nausea, and normally begin 1 to 2 weeks after infection, lasting 2 to 6 weeks. Chronic infections lasting months to years have also been reported. Prescription drugs are available to treat giardiasis, but in addition plenty of fluid intake is necessary to counteract the dehydration due to diarrhea.

Entamoeba histolytica (Amebiasis)

Once ingested, the cysts undergo excystment in the small intestine of the new host. New trophozoites form and migrate to the large intestine to multiply. As a result, both cysts and trophozoites are released to the environment via the feces of an infected person; the trophozoites will die rapidly, but the cysts will remain infective. In as many as 90% of infections the trophozoites reencyst and the infection remains asymptomatic and self-limiting; but disease symptoms may recur. Acute amoebic colitis has a gradual onset of 1 to 2 weeks, involving abdominal pain and diarrhea. Several different antibiotics are available to treat amebiasis (see Chapter 23, Human Age and Microorganisms).

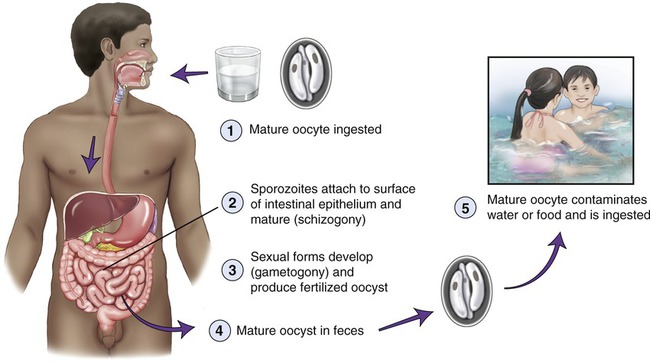

Cryptosporidiosis

This parasitic diarrheal disease cryptosporidiosis, also known as “crypto,” is caused by the protozoan Cryptosporidium and is spread via the fecal–oral route, through contaminated water, and via uncooked or cross-contaminated food. After infection the parasite lives in the intestine of the animal or human and is released with the feces (Figure 12.7). Because of the parasite’s outer shell it can survive outside the body of the host for extended periods of time. Furthermore, the organism is rather resistant to chlorine and chlorine-based disinfectants and can live for days in chlorine-treated swimming pools.

Helminths

As indicated previously, helminths are not microorganisms, they are macroscopic, multicellular, eukaryotic worms found throughout the globe. What is interesting to microbiologists is the fact that their eggs and larvae are microscopic. The distinguishing traits, life cycle, and classification are described in Chapter 8 (Eukaryotic Microorganisms). This chapter highlights some of the most common human intestinal parasitic helminths.

Taeniasis

Taeniasis, the term for human tapeworm infection, is normally acquired by consuming raw or undercooked meat of infected animals. Taenia saginata is common in beef, and Taenia solium is common in pigs (Figure 12.8). The larvae present in the infected meat will then grow into an adult tapeworm in the human intestine, where it can live for years and grow very large—longer than 12 feet. Humans are the only definitive host for the two organisms (see Chapter 8) and both species are distributed worldwide. Tapeworm infestation usually does not cause any symptoms, and the infection is normally recognized by the presence of moving worm segments in the stool. Infected individuals can expose other individuals via food handling with contaminated hands, and can also self-infect if personal hygiene is deficient. Tapeworm infestation can be treated and eradication of the tapeworm is expected after treatment.

Pinworm Infection

The best known human pinworm, also known as the “seatworm,” is Enterobius vermicularis, a small, white intestinal worm (nematode) found in soil, dust, food, and water. It lives in the rectum of humans (Figure 12.9). Pinworm infections are the most common worm infections in the United States, with school-age children and preschoolers being at highest risk. The female pinworm leaves the intestines through the anus, usually during the night, and deposits the eggs on the surrounding skin. This causes itching around the anus, and disturbed sleep in the infected person. Pinworm eggs can survive up to 2 weeks on clothing, bedding, or other objects. Infection can occur after accidentally ingesting pinworm eggs from contaminated surfaces or fingers. Pinworm infections can be treated with either a prescription drug such as mebendazole, or over-the-counter drugs such as pyrantel pamoate, involving a two-dose course.

Ascariasis

Ascaris infection, or ascariasis, caused by Ascaris lumbricoides (Figure 12.10) is the most common nematode infection of humans worldwide. The infection is most common in tropical and subtropical areas but is also endemic in rural areas of the southeastern United States. Ascaris eggs are found in human feces and when soil becomes contaminated, the eggs become infectious after a few weeks. Infection occurs after accidental ingestion of infectious Ascaris eggs (see Chapter 8 [Eukaryotic Microorganisms] for its life cycle). The parasite can enter the soil when contaminated with human feces, and the eggs remain viable in the soil for long periods of time. Subsequently, vegetables and fruits grown in this soil become contaminated; when humans consume them they become infected.

Hookworm Infections (Necatoriasis)

Necatoriasis is caused by hookworms, parasitic nematodes that live in the small intestine of mammals such as dogs, cats, and humans. The two species that are capable of causing human infections are Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus. Once the adult hookworm reaches the intestine (see Chapter 8 [Eukaryotic Microorganisms] for the life cycle) it attaches itself to the villi of the intestinal wall and sucks blood from its host to obtain nutrition. A single Necator americanus can take about 30 µl of blood daily; the larger Ancylostoma duodenale can take up to 260 µl/day. Slight infections may appear asymptomatic, but others may cause abdominal discomfort, diarrhea, cramps, anorexia, and weight loss. Heavy infections generally lead to iron-deficient anemia. Hookworm can be treated when it is still on the skin, in the migrating stage, and during the intestinal stage.

Summary

• The gastrointestinal tract (GI) is a common and easily accessible portal of entry for microbes or their toxins, and both have the ability to cause illnesses. Therefore, food- and waterborne diseases are a major public health concern worldwide.

• Many different organisms are responsible for infections of the GI tract, ranging from the oral cavity with dental caries and periodontal disease, to the stomach with peptic ulcers, and the intestines with gastroenteritis.

• Salmonellosis, typhoid fever, shigellosis, campylobacteriosis, Escherichia spp. gastroenteritis, and yersiniosis are all bacterial infections of different origins but only somewhat different symptoms and outcomes. They all cause a form of gastroenteritis. All these illnesses occur only when the organism is present in the body and has caused an active infection.

• Bacterial gastrointestinal intoxication is a condition caused by the consumption of bacterial toxins. Organisms capable of causing this type of toxemia include Clostridium botulinum, the causative agent for botulism, Staphylococcus aureus, Vibrio cholerae, Bacillus cereus, and some other toxin-producing Bacillus species.

• In general, bacterial GI tract infections are transmitted through contaminated food, contaminated water supplies, by the fecal–oral route, or by person-to-person contact. Bacterial intoxication, on the other hand, is usually due to faulty food preparation, storage, and/or handling of the food.

• The leading causes of viral gastroenteritis are the rotavirus and norovirus families, but other viruses also have been implicated in outbreaks, including astroviruses, caliciviruses, enteric adenoviruses, and hepatitis viruses.

• Viral gastroenteritis is usually mild, but can become toxic or even lethal if rehydration is not maintained.

• Mycoses that affect the GI tract are generally opportunistic and typically do not affect people with a healthy immune system. However, certain fungi can also cause problems in otherwise healthy people. These include Aspergillus flavus, Claviceps purpurea, and Candida albicans.

• Some protozoans are human parasites capable of causing debilitating and deadly diseases. These include Giardia intestinalis, Balantidium coli, Entamoeba histolytica, and Cryptosporidium.

• Helminths are not microorganisms but their eggs and larvae are of microscopic size and capable of causing illnesses in the human GI tract. These infections include taeniasis (tapeworm infection), pinworm infections, ascariasis, and hookworm infections.

Review Questions

1. All of the following are components of the gastrointestinal tract except:

2. Microbial life on teeth was first observed by:

3. Many peptic ulcers are due to:

4. Bacillary dysentery is also called:

5. There are __________ known forms of gastroenteritis caused by E. coli.

6. Bacillus intoxication is caused by:

7. The most common cause of infectious diarrhea in infants and children is by:

8. A group of (+) ssRNA viruses that have been isolated from birds, cats, dogs, pigs, sheep, cows, and humans, and are a major cause of gastroenteritis, are:

9. Which of the following organisms produce aflatoxin, a carcinogenic substance?

10. The human pinworm Enterobius vermicularis lives in the __________ of humans.

11. A periodontal disease that is restricted to the gums is an inflammation called __________.

12. The term “stomach flu” really refers to __________.

13. Botulism is caused by __________.

14. Staphylococcal intoxication is caused by Staphylococcus __________.

15. “Thrush” is caused by __________.

16. Differentiate between bacterial infection and bacterial intoxication.

17. Describe the cause, transmission, symptoms, prevention, and treatment of cholera.

18. Describe rotavirus infections; include prevalence, transmission, prevention, and treatment.

19. Discuss giardiasis; include causative agent, transmission, symptoms, and treatment.

20. Name and discuss the two organisms that cause hookworm infections in humans.