Mohan P. Venkatesh, Karen M. Adams and Leonard E. Weisman

A newborn infant is uniquely susceptible to infectious diseases. This chapter presents causes of infectious diseases with particular emphasis on prevention, history, presenting signs and symptoms, laboratory data, treatment, and parent teaching methods of prevention applicable to the care of the neonate. Abbreviations for this chapter are listed in Box 22-1.

BOX 22-1

| AIDS | Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome |

| CF | Complement fixation (test) |

| CIE | Counterimmunoelectrophoresis |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| CRS | Congenital rubella syndrome |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| DFA | Direct fluorescent antibody |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| FA | Fluorescent antibody (test) |

| FAMA | Fluorescent antibody to membrane antigen |

| FTA-ABS | Fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (test) |

| GBS | Group B Streptococcus |

| HbsAg | Hepatitis B surface antigen |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| IAHA | Immune adherence hemagglutination |

| IFA | Indirect fluorescent antibody (test) |

| IHA | Indirect hemagglutination inhibition (test) |

| IPV | Inactivated poliovirus vaccine |

| IUGR | Intrauterine growth restriction |

| LA | Latex agglutination (test) |

| MHA-TP | Microhemagglutination test for Treponema pallidum infection |

| NAAT | Nucleic acid amplification test |

| OPV | Oral poliovirus vaccine |

| PCP | Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia* |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| RPR | Rapid plasma reagin (test) |

| RT-PCR | Reverse transcriptase PCR |

| VDRL | Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (test) |

| *Formerly Pneumocystis carinii. |

|

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

An infection occurs when a susceptible host comes in contact with a potentially pathogenic organism. When the encountered organism proliferates and overcomes the host defenses, infection results. Sources of infection in a newborn can be divided into three categories: (1) transplacental acquisition (intrauterine infection), (2) perinatal acquisition during labor and delivery (intrapartum infection), and (3) hospital acquisition in the neonatal period (postnatal infection) from the mother, hospital environment, or hospital personnel.

In general, most infecting organisms can, under the proper circumstances, cross the placenta or ascend from the birth canal and invade the at-risk neonate. These infections may result in abortion, stillbirth, and disease present at birth or in the neonatal period.

The main goal is to prevent infections in the fetus and newborn. Unfortunately, few proven measures exist for the prevention of transplacentally or perinatally acquired infections. These measures are important, because most nonbacterial infections (except syphilis and possibly toxoplasmosis, cytomegalovirus [CMV] infection, and herpes simplex) do not respond to current therapy.

ETIOLOGY

Thorough data collection for diagnosis of infectious diseases includes a review of the perinatal history, signs and symptoms, and laboratory data. Intrauterine, intrapartum, or neonatal disease may be caused by a wide variety of organisms, many of which are discussed in this chapter.

SPECIFIC INFECTIOUS DISEASES

The following specific infectious diseases are grouped according to their source of infection.

Transplacental (Intrauterine) Acquisition

HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS INFECTION AND ACQUIRED IMMUNODEFICIENCY DISORDER

Prevention

The primary risk to infants for infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the causative agent of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), is intrauterine, intrapartum, and postpartum exposure to a mother with HIV infection. HIV has been isolated from blood and many body fluids. Epidemiologic evidence has implicated only blood, semen, vaginal secretions, and breast milk in transmission. In countries such as the United States, where safe alternatives exist, mothers with HIV infection should be discouraged from breast feeding. 93 HIV testing should be recommended and encouraged to all pregnant women. 5,6,114

Because the medical history and examination cannot reliably identify all patients infected with HIV (or other bloodborne pathogens) and because during delivery and initial care of the infant, perinatal care providers are exposed to large amounts of maternal blood, Standard Precautions (e.g., gloves) should be consistently used for all patients when handling the placenta or infant until all maternal blood has been washed away. 5,50

Data Collection

History

HIV infection in the mother is acquired primarily sexually or by intravenous (IV) drug abuse. Infection may be asymptomatic. Transmission from an untreated infected mother to the fetus or infant occurs in 13% to 39% of births. Approximately 40% of transmissions are before birth and the rest around the time of delivery. Two thirds of infections occurring before delivery are caused by transmission within the 14 days before delivery. 5 A high maternal plasma viral load, high cervico-vaginal viral load, low CD4 + lymphocyte count, advanced maternal illness, an increase in exposure of the fetus to maternal blood, premature delivery, prolonged labor, longer duration of rupture of membranes before delivery, and mode of delivery all increase perinatal transmission of HIV infection. 4,6,113

Signs and Symptoms

Infants with perinatally acquired HIV infection uncommonly have symptoms in the neonatal period, but the majority of these infants present with clinical illness by 24 months of life (median age at onset of symptoms is 11 to 12 months). One fifth of infants infected with HIV perinatally develop serious disease or die in the first year of life. 114 Symptoms include failure to thrive, developmental disabilities, neurologic dysfunction, hepatosplenomegaly, generalized lymphadenopathy, parotitis, persistent oral candidiasis (thrush), and chronic or recurrent diarrhea. Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia is frequently seen in these infants. HIV-infected infants commonly have osteomyelitis, septic joints, pneumonia, sepsis, meningitis, and otitis media with common organisms (e.g., Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae type b), and these infections may be recurrent. 4,114

Laboratory Data

HIV nucleic acid detection by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of DNA extracted from peripheral blood mononuclear cells is the gold standard for early diagnosis of infected infants, and results are available within 24 hours. 114 About 30% of HIV-infected infants have a positive DNA PCR assay from samples obtained within 48 hours of age; 93% have detectable HIV DNA by 2 weeks; and almost all by 1 month of age. The primary serologic laboratory test for HIV antibody is the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The Western blot test is used for confirmation of positive ELISA results. Differentiation of the child with passively acquired antibody from the infant with active infection is critical but difficult. Acquired antibody is undetectable in 75% of infants by 12 months of age and in most infants by 15 to 18 months of age. Infants have also been described with negative serology but active infection. 79 Virus isolation by culture is difficult and expensive, and p24 antigen detection is less sensitive. 4,72 The plasma HIV RNA PCR assay is currently used for quantifying the viral load but not routinely used for diagnosis. Although hypogammaglobulinemia has been reported (<10% of patients), hypergammaglobulinemia usually is present.

Treatment

Antiretroviral therapy with zidovudine (ZDV) alone or in combination with other antiretroviral agents reduces HIV transmission from infected mothers to their newborns. 69,78,79ZDV should be given to infants of infected women beginning at 8 to 12 hours of life and should be continued for 6 weeks.6,69 ZDV is administered orally at 2 mg/kg body weight/dose every 6 hours. 6 If the infant is confirmed to be HIV positive, ZDV is changed to a multidrug antiretroviral regimen. Infants who are perinatally infected with HIV are at high risk for developing Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia (PCP, formerly known as Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia) early in the first year of life. Guidelines recommend initiating prophylaxis for the prevention of PCP for all HIV-exposed infants at 4 to 6 weeks of age, regardless of their CD4 + cell count. For infants receiving ZDV, PCP prophylaxis should begin after completion of the 6-week course of ZDV. The recommended PCP prophylaxis may be provided by 150 mg/m 2/day (5 mg/kg/day) of trimethoprim (TMP) and 750 mg/m 2/day (25 mg/kg/day) of sulfamethoxazole (SMX) administered in two divided doses for three consecutive days in a week. 4,6,69 TMP/SMX prophylaxis should be continued through the first year of life or until HIV infection is reasonably excluded. 6,69

Parent Teaching

Care of an infant at risk for HIV requires close and long-term follow-up. Involvement of the parents is essential to this process. Education of the parents will maximize the success of such a care plan, and utilization of all available community resources should provide additional support. In addition to the rationale for and importance of the medical management just outlined, the parents should be counseled concerning the need for the following:

• Immunizations following the American Academy of Pediatrics schedule

• Rapid consultation with the infant’s physician if he or she is exposed to varicella (may need treatment with varicella-zoster immune globulin [VZIG] within 96 hours of exposure) or measles (needs immune globulin intramuscularly regardless of immunization status)

• Rapid consultation with the physician for tetanus-prone wounds (requires tetanus immune globulin irrespective of immunization status)

• Rapid consultation with the physician for thrush, a diaper rash, or any other signs or symptoms of illness

Prevention of infections is important, and this requires good handwashing, regular bathing, appropriate food preparation skills (wash bottles, nipples, and pacifiers), and good skin care (changing diapers and moisturizing skin in other areas to prevent drying and cracking). 4

CYTOMEGALOVIRUS INFECTION

Prevention

There are no practical methods for preventing CMV infection. Avoiding exposure is virtually impossible because of the ubiquitous and asymptomatic nature of the infections. Avoiding unnecessary blood transfusions or using CMV-seronegative blood donors, white blood cell–depleted blood products, or frozen deglycerolized blood cells has proved to be important in minimizing the occurrence of postnatally acquired CMV, particularly in premature infants. 4,5

The question frequently arises about assignment of staff to infants with a possible diagnosis of CMV infection. Staff members who may be pregnant have heightened concern about this issue. Staff members should be aware that many infants with CMV infection are often asymptomatic and therefore not identified while in the hospital. To avoid any problems, staff members should employ good handwashing technique with all infants. Wearing gloves when handling urine and other secretions is a strategy that can also be employed by staff members who are working in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) and are pregnant or of childbearing age. The actual risk for an infected infant’s transmitting disease to a susceptible health care worker is unknown but probably small. 4

Data Collection

History

Signs and Symptoms

An infant with CMV infection is usually asymptomatic. Congenital manifestations include intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), neonatal jaundice (increased direct fraction), purpura, hepatosplenomegaly, microcephaly, seizures, intracerebral calcification, chorioretinitis, and progressive sensorineural hearing loss. 12

Laboratory Data

CMV may be cultured from urine, pharyngeal secretions, and peripheral leukocytes. Isolation of the virus within 3 weeks of birth indicates transplacental acquisition. A paired sera demonstration of a fourfold titer rise or histopathology demonstration of characteristic nuclear inclusions in certain tissues can confirm infection. Examining the urine for intranuclear inclusions is not helpful. PCR detection of viral DNA in tissues and cerebrospinal fluid is also available. 4

Treatment

Ganciclovir, foscarnet, valganciclovir, and cidofovir are the only licensed antiviral agents effective against CMV. These drugs are approved only for treatment of life- and sight-saving disease. In a randomized controlled trial that evaluated 42 neonates with congenital CMV infection involving the central nervous system (CNS), 6 weeks of IV ganciclovir therapy prevented hearing deterioration at 6 months. However, two thirds of neonates treated with ganciclovir had significant neutropenia. 67 More studies are necessary before ganciclovir can be routinely recommended in congenital CMV infection involving the CNS. 4,33

Parent Teaching

The need for good handwashing technique by parents and caregivers of infants with suspected CMV should be included in discharge instructions.

RUBELLA

Prevention

Medical personnel should ensure that all mothers have a protective hemagglutination titer before conception. If the woman is susceptible, vaccinate her with rubella vaccine before conception and advise her that she should avoid conception for 28 days after receiving the vaccine. 4,74 If a woman is found to lack immunity to rubella during pregnancy, she should receive rubella immunization in the postpartum period even if she is breast feeding. 43,74

Data Collection

History

Signs and Symptoms

Congenital manifestations of rubella include IUGR, sensorineural deafness, cataracts, neonatal jaundice (increased direct fraction), purpura, hepatosplenomegaly, microcephaly, chronic encephalitis, chorioretinitis, and cardiac defects (especially patent ductus arteriosus and peripheral pulmonic stenosis). Less frequent manifestations include bone lesions and pneumonitis. 4

Laboratory Data

The virus may be isolated from the throat, blood, urine, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). A paired sera demonstration of a fourfold titer rise, such as an indirect hemagglutination (IHA) inhibition test or an indirect fluorescent antibody (IFA) test, is diagnostic. The IHA test generally has been replaced by one of several more sensitive methods including enzyme linked immunoassay, or latex agglutination, and reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assays. 4,18

Parent Teaching

Infants with congenital rubella syndrome (CRS) may secrete the virus for many years. This requires that discharge instructions include preventive strategies that should be employed to decrease the chance of contact of susceptible pregnant women with the infant. Parents should be informed of their responsibility to ensure that potentially seronegative women of childbearing age avoid direct contact with the infant.4 The challenge arises to impress this on the family and at the same time avoid ostracizing the infant or negatively affecting the parent-infant attachment process. In discharge planning with these families, a collaborative approach should be employed, using community health, medical, nursing, and social work input and support. Another challenge is to impress on parents that an infant exposed to rubella during pregnancy may appear normal at birth, but the first appearance of some CNS symptoms may extend into childhood. Thus families and clinicians should keep a watchful eye on these children during the early childhood years. 74

SYPHILIS

Prevention

Pregnant women should avoid exposure to syphilis. Monitor the serum early and late in pregnancy, and treat the mother for the appropriate stage of disease. Erythromycin, previously used in penicillin-sensitive women, is not considered adequate treatment during gestation because of 30% treatment failure rates in adults and failure to establish a cure in newborns as a result of poor transplacental passage of erythromycin. Infants born to women treated with erythromycin should be considered high risk for infection and appropriately evaluated and treated. If penicillin allergy is confirmed in the pregnant woman, acute desensitization is necessary. Desensitization can be accomplished using increasing doses of oral penicillin over 4 to 6 hours. 106

Data Collection

History

A congenital infection may be manifested by a multisystem disease. A primary syphilitic chancre on the cervix or rectal mucosa in a mother may be unnoticed. 106

Signs and Symptoms

An infant exposed to syphilis may be asymptomatic at birth, or virtually all organ systems may be involved. Clinical findings may include hepatitis, pneumonitis, bone marrow failure, myocarditis, meningitis, nephrotic syndrome, rhinitis (snuffles), a rash involving the palms and soles, and pseudoparalysis of an extremity. 4,26,106

Laboratory Data

The microscopic darkfield examination identifies spirochetes from nonoral lesions. Nonspecific, nontreponemal reaginic tests, such as Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) tests and rapid plasma reagin (RPR) tests, followed serially with a rise or absence of fall after birth, are useful for screening. 26,106 Specific treponemal antibody serologic tests, such as a fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) test or a microhemagglutination test for Treponema pallidum (MHA-TP), provide diagnostic confirmation of a reactive nontreponemal test, but an FTA-ABS IgM test is unreliable. 26,106 False-positive results may occur with nontreponemal tests secondary to other medical conditions or other spirochetal diseases. Therefore confirmation of diagnosis is necessary. 4 A long-bone x-ray examination showing metaphysitis or periostitis may help in diagnosing syphilis. VDRL tests on CSF are mandatory in all infants suspected of having congenital syphilis. When the diagnosis of active congenital syphilis is equivocal, often it is best to treat and ascertain the diagnosis by serial serologic determinations. 4,26,106

Treatment

Table 22-1 outlines the treatment for syphilis. 4

| Condition | Treatment |

|---|---|

| SEPSIS AND/OR MENINGITIS | |

| Initial Therapy | |

| Early onset | Intravenous (IV) ampicillin and gentamicin or IV amikacin (if gentamicin-resistant organisms are present in nursery, ampicillin plus cefotaxime is a suitable alternative, particularly if meningitis is present). |

| Late onset | IV vancomycin plus cefotaxime or IV aminoglycoside (see “Early onset”). |

| ONCE SPECIFIC ORGANISMS ARE IDENTIFIED | |

| Group B Streptococcus | IV ampicillin and gentamicin for 10 to 14 days (gentamicin may be discontinued if strain is not tolerant). |

| Coliform species | IV ampicillin and gentamicin for 10 to 14 days (cefotaxime may replace gentamicin). |

| Listeria monocytogenes | IV ampicillin and IV gentamicin for 14 to 21 days. |

| Enterococci | Same as for Listeria monocytogenes. For ampicillin resistance, use vancomycin. |

| Group A Streptococcus | IV penicillin G for 10 to 14 days. |

| Group D Streptococcus (non-enterococcus) | Same as for Group A Streptococci. |

| Staphylococcus aureus | IV nafcillin for 10 to 14 days; IV vancomycin for methicillin-resistant strains. |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | IV vancomycin for 10 to 14 days. |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | IV ceftazidime and aminoglycoside for 10 to 14 days. |

| Anaerobes | IV metronidazole, clindamycin, or meropenem. |

| PNEUMONIA | |

| Group B Streptococcus | Same as for sepsis (respiratory distress syndrome may mimic pneumonitis and vice versa). |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Same as for sepsis. |

| Chlamydia trachomatis | Oral (PO) erythromycin for 14 days. |

| Pneumocystis jiroveci | PO or IV trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole, or IV pentamidine isethionate. |

| Pertussis | PO or IV azithromycin for 5 days (clinical course is unchanged, but shedding of organism is diminished significantly). |

| Other organisms | Same as for sepsis. |

| SKIN AND SOFT TISSUE INFECTIONS | |

| Impetigo | IV or intramuscular (IM) nafcillin; PO cephalexin for 7 days (depending on clinical severity). For methicillin-resistance, use vancomycin. Also consider topical mupirocin. |

| Group A Streptococcus infections | IV penicillin G for 7 days. |

| Breast abscess | IV nafcillin and gentamicin for 7 days pending identification of etiologic agent (change to IV penicillin if Streptococcus is etiologic agent; IV ampicillin or gentamicin should be used for coliform species pending sensitivities); value of surgical drainage is individualized; vancomycin for methicillin-resistant strains. |

| Omphalitis and/or funisitis | IV nafcillin for 7 days (penicillin may be used if infection is caused by group A or B streptococci); if gram-negative rods, consider gentamicin or cefotaxime also. |

| GASTROINTESTINAL INFECTIONS | |

| Salmonella species | IV ampicillin for 7 to 10 days; or IV cefotaxime or ceftriaxone for 7 to 10 days depending on sensitivities (focal complications of meningitis and arthritis should be monitored closely). |

| Shigella species | PO trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole or PO or IV ampicillin, depending on sensitivities. |

| Necrotizing enterocolitis | IV ampicillin and IV gentamicin for 2 to 3 weeks (if Pseudomonas is isolated, IV ceftazidime or piperacillin/tazobactam combination may be substituted for ampicillin); supportive measures (gastrointestinal suction) are appropriate. |

| OSTEOMYELITIS OR SEPTIC ARTHRITIS | |

| Group B Streptococcus | IV penicillin G for 21 days minimum. |

| Staphylococcus aureus | IV oxacillin for 21 days minimum. |

| Coliform species | IV gentamicin for 21 days (IV ampicillin for 21 days minimum if organism is sensitive). |

| Gonococcus species | IV penicillin G for 10 days. |

| Unknown | IV oxacillin and gentamicin for 21 days minimum. |

| URINARY TRACT INFECTIONS | Suspect predisposing anatomic defect if urinary tract infection; individualize workup and follow-up. |

| Coliform species | Gentamicin, 3 mg/kg/day divided q 8 hr for 10 days. |

| Enterococcus species | Ampicillin, 30 mg/kg/day divided q 8 hr for 10 days. |

| MISCELLANEOUS CONDITIONS | |

| Congenital syphilis | If more than 1 day of treatment is missed in either of the following regimens, the entire course should be restarted. |

| Without central nervous system (CNS) involvement | IM procaine penicillin G (50,000 units/kg) daily for 10 to 14 days (follow-up Venereal Disease Research Laboratory [VDRL] test results should revert to negative if treatment is adequate by 1 year). |

| With CNS involvement | IV aqueous crystalline penicillin G 100,000-150,000 units/kg/day, administered as 50,000 for a total units/kg/dose q 12 hr for the first 7 days of life and q 8 hr thereafter for 10 days. Repeat lumbar puncture about every 6 months until results are normal. |

| Toxoplasmosis |

PO sulfadiazine, 100-120 mg/kg/day divided q 12 hr and PO pyrimethamine, 1 mg/kg/day divided q 12 hr (duration of treatment is debatable but should be long [i.e., months]; supplemental folic acid, 1 mg/day, should be added).

Ocular, CNS, or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) involvement may require additional therapy.

|

| Herpes simplex infections | IV acyclovir, 20 mg/kg/dose q 8 hr, for 14 days if skin or mucous membrane involvement; 21 days if CNS involvement. |

| Conjunctivitis | |

| Chlamydia species | PO erythromycin for 10 days (topical may be ineffective). |

| Gonococcus species | IV penicillin G for 10 days; cefoxitin for penicillin-resistant strains. |

| Otitis media | |

| In otherwise normal neonate | PO amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (Augmentin), 40 mg/kg. |

| In neonate with nosocomial infection | PO or IV ampicillin and IV gentamicin (if there is no response to treatment, consider diagnostic tympanocentesis; Staphylococcus aureus and coliform species may be present). |

Parent Teaching

Adequate follow-up of both symptomatic and asymptomatic neonates is very important. A physical evaluation should be conducted at 1, 2, 3, 6, and 12 months. Serologic testing should be performed at 3, 6, and 12 months after completion of therapy regimen, or until titer decreases fourfold. Noninfected or adequately treated infants’ titers should be decreased by 3 months and nonreactive by 6 months. If titers fail to decline or if they increase or are still present after 6 to 12 months of age, the infant should be reevaluated and retreated. Infants with neurosyphilis should have a repeat CSF examination every 6 months until it is normal and VDRL nonreactive. If CSF VDRL is still reactive at 6 months or CSF white cell count is not decreasing at each reexamination or is abnormal at 24 months, retreatment is indicated. 4

TOXOPLASMOSIS

Prevention

Women should avoid unnecessary exposure to raw meat, cat feces, and eating fruits or vegetables not peeled or washed thoroughly. Using a pair of gloves when emptying the litter box may provide protection if the pregnant woman (or a woman attempting to become pregnant) must empty the litter box. 4 A pregnant woman (or woman attempting to become pregnant) should use hot soapy water to wash her hands immediately after exposure to any infectious source, even after wearing gloves. 17

Data Collection

History

Congenital infections are represented by a wide range of disease, from asymptomatic disease to profound symptomatic disease, and all require treatment. 4,111 Mothers may have noted an influenza-like illness, posterior cervical adenitis, or chorioretinitis but usually lack accompanying signs or symptoms. A history of exposure to cat feces or ingestion of raw meat occasionally may be obtained. 5,60,111

Signs and Symptoms

Laboratory Data

Isolating Toxoplasma gondii from blood or body fluids is difficult and tedious. Cysts may be found in the placenta or tissues of a fetus or newborn. 81 Most congenitally infected infants have a Sabin-Feldman dye test titer greater than 1:1000 at birth.

Treatment

Table 22-1 outlines the treatment of toxoplasmosis. 4

Perinatal Acquisition During Labor and Delivery

CHLAMYDIA TRACHMOMATIS INFECTION

Prevention

Data Collection

History

Signs and Symptoms

Conjunctivitis may be manifested as congestion and edema of the conjunctiva, with minimal discharge developing 1 to 2 weeks after birth and lasting several weeks with recurrences, particularly after topical therapy. Infants with pneumonitis usually do not have a fever but have a prolonged staccato cough, tachypnea, mild hypoxemia, and eosinophilia. Otitis media and bronchiolitis also may occur. 4,118

Laboratory Data

Definitive diagnosis is made by isolating the organism in tissue culture and by nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) (e.g., PCR). Demonstrating chlamydial antigen in clinical specimens by the direct fluorescent antibody method or enzyme immunoassay is very reliable. To enhance the likelihood of obtaining an adequate sample, scrape the lower conjunctiva (for conjunctivitis) or obtain deep tracheal secretions or a nasopharyngeal aspirate (for pneumonia). NAATs are not recommended for nasopharyngeal aspirates. Scraping conjunctival epithelial cells and demonstrating characteristic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies by a Giemsa stain is diagnostic. Although serologic tests for conjunctivitis are unreliable, a significant titer rise in IgM specific antibody may be reliable in cases of pneumonia. Eosinophilia (>300 eosinophils/mm 3) may suggest Chlamydial pneumonia. 4,118

ENTEROVIRUS (COXSACKIEVIRUS A, COXSACKIEVIRUS B, ECHOVIRUS, AND POLIOMYELITIS) INFECTIONS

Enterovirus infections are the most commonly diagnosed viral infections in the neonatal intensive care unit, and coxsackievirus B1 was the most common in 2007 by the National Enterovirus Surveillance System. 23,65,119

Prevention

To prevent poliomyelitis, it is essential to maintain poliomyelitis immunity with active immunization before conception. Passive protection with pooled human serum globulin may help in selected exposures (0.2 mL/kg body weight, given intramuscularly). Routine nursery infection control procedures must be observed. It is recommended that only inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV) be used in the nursery. The IPV is administered intramuscularly and contains no live virus, whereas oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV) (OPV is no longer available in the United States) is administered orally and contains live but attenuated virus, which has been reported to cause infection in immunocompromised patients. 4

Data Collection

History

Infection may occur year-round but is more prevalent from June to December in temperate climates. Most enterovirus infections are asymptomatic. Poliomyelitis is rare because of a high level of vaccine-induced immunity in most of the world. 4

Signs and Symptoms

Mothers with enteroviral infections are usually mildly ill, with fever or diarrhea. Infants may be asymptomatic or have fever or diarrhea. Infants who acquire the infection without maternal antibody have severe disease and high mortality. Fever, irritability, lethargy, and rash are common. Severe disease with sepsis, meningoencephalitis, myocarditis, pneumonia, hepatitis, or coagulopathy may occur. 1 Prematurity, early onset of illness (<7 days), maternal history of illness, high white blood cell count (≥15,000/mm 3), and low hemoglobin (<10.7 g/dL) have been shown to be risk factors of severe infection. 73

Laboratory Data

The virus may be isolated from the throat, rectum, or CSF. Isolating coxsackievirus A may require suckling mouse inoculation. Serologic screening is impractical because of the large number of serotypes. PCR assay for enterovirus RNA in CSF and other specimens is available and is more sensitive than viral isolation. 4

Treatment

The antiviral agent pleconaril is undergoing clinical evaluation in neonates to treat enteroviral infections.98 Pleconaril has a novel mechanism of action by preventing the viral attachment and entry into the host cells and seems to be well tolerated in neonates. 2,99 Hand hygiene is paramount to control spread of enteroviral infections. 4

GROUP B STREPTOCOCCUS INFECTION

Prevention

Intrapartum (during labor) treatment of the mother with penicillin significantly decreases disease caused by group B Streptococcus (GBS) in the neonate and maternal postpartum endometritis.4,15,76,83 Neonatal sepsis has been reported with less than 4 hours of maternal antibiotics at term and with up to 48 hours in preterm infants. 121 Five to fifteen percent of clinical GBS isolates are resistant to clindamycin and 16% to 22% to erythromycin, and antibiotic prophylaxis with clindamycin in penicillin-allergic women may not prevent neonatal GBS disease. 32,34,58,77

Data Collection

Treatment

Table 22-1 outlines the treatment of group B Streptococcus infection.

Parent Teaching

See the section on bacterial infections and bacterial sepsis on pp. 571-572 and 575.

HEPATITIS B

Prevention

Prenatal screening of women for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) is indicated and is cost effective. Use of active and passive immunization in infants born to HBsAg-positive mothers is indicated (Tables 22-2and22-3).4Use of active immunization for infants born to HBsAg-negative women is recommended at birth by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. However, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) analyzed data from the 2006 National Immunization Survey (for the years 2003 to 2005) showed only 50.1% of newborns had hepatitis B vaccine by day 3 of life with a considerable geographical variation. 24

| HBIG, Hepatitis B immune globulin; HSIG, human serum immune globulin; TIG, tetanus immune globulin (human); ZIG, zoster immune globulin. | ||||

| *Should be used in conjunction with active immunization with hepatitis B virus (HBV) vaccine (see Table 22-3). | ||||

| Modified from Remington JS, Klein JO, editors: Infectious diseases of the fetus and newborn infant, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2001, Saunders. | ||||

| Disease | Indications | When to Use | Product | Dose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatitis A | Active infection in mother or close family contacts | As soon as possible | HSIG | 0.02-0.04 mL/kg body weight, give intramuscularly (IM) |

| Hepatitis B | Mothers with acute type B infection or who are antigen (+) | As soon as possible (within 12 hr) | HBIG* | 0.5 mL/kg body weight IM |

| Tetanus | Inadequately immunized mothers with contaminated infant (e.g., dirty cord) | As soon as possible | TIG | 250 units given IM (optimal dose not established) |

| Varicella | Infant born to a mother who develops lesions <5 days before delivery or within 2 days after delivery | Within 72 hours of birth | ZIG | 2 mL given IM |

| HBsAg, Hepatitis B surface antigen. | ||||

| *As soon as possible. |

||||

| Disease | Indication | When to Use | Product | Dose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatitis B | HBsAg-positive or HBsAg-negative | 3 separate doses: at birth*; at 1 month; and at 6 months | Recombivax HB® | 0.5 mL intramuscularly (IM) |

| Engerix-B® | 0.5 mL IM | |||

| Pertussis | To control outbreak in nursery | As soon as possible | Pertussis vaccine | 0.25-0.5 mL administered subcutaneously |

| Tuberculosis | Selected infants at risk for contracting tuberculosis | As soon as possible | Calmette-Guérin bacillus (CGB) | 0.1 mL given intradermally and divided into 2 sites over deltoid muscle |

Data Collection

History

Mothers who are HBsAg positive because of the chronic carrier state or acute disease before delivery may pass the infection to their infants at delivery. 5 Women at high risk include those of Asian, Pacific Island, or Alaskan Eskimo descent; women born in Haiti or sub-Saharan Africa; and those with a history of liver disease, IV drug abuse, or frequent exposure to blood in a medical-dental setting.

Signs and Symptoms

A neonate with hepatitis B is usually asymptomatic. Occasionally, infected infants demonstrate elevated liver enzymes or acute fulminating hepatitis. 4 Neonatal infection with subsequent chronic carriage has been implicated in the development of primary hepatocellular carcinoma later in life.

Laboratory Data

Most infants at risk for acquiring hepatitis from their mother are HBsAg negative at birth. Many untreated infants become HBsAg positive 4 to 12 weeks after birth and become lifelong asymptomatic carriers or develop hepatitis B. 4

HEPATITIS C

Prevention

Neonates acquire hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection mostly through vertical transmission from the mother and rarely through transfusion of hepatitis C–contaminated blood products. Vertical transmission rates from the mother to the infant vary (≈5%), and risk factors associated with increased transmission are HCV viral load, co-infection with HIV, rupture of membranes more than 6 hours, and internal fetal monitoring. 31,75,87,88 Reducing viral load by maternal antiviral therapy, especially in HIV co-infected women, and avoiding internal fetal monitoring are interventions that can reduce transmission but have not been evaluated. Breast feeding is not associated with increased rates of transmission and is not contraindicated. 4 Screening of blood products for HCV is mandatory for prevention of transfusion-related HCV infection.

Data Collection

History

One to two percent of pregnant women in the United States are seropositive for HCV, but vertical transmission occurs only if the mother is HCV RNA positive at the time of delivery. 4 HCV RNA titers rise many weeks after birth in infants, indicating a perinatal acquisition rather than an intrauterine transmission. 31

Signs and Symptoms

Neonates with perinatal acquisition of HCV infection are usually asymptomatic without jaundice and with normal or only mildly elevated liver transaminase levels. 88,95,115 Progression to chronic hepatitis is common and occurs in approximately 80% of infected infants. Liver biopsies in infants with perinatally acquired HCV during follow-up show evidence of chronic inflammation. A small percentage (20%) of infants may spontaneously resolve their infection. 40

Laboratory Data

The essential diagnostic feature is HCV RNA positivity on at least two occasions by PCR. Sensitivity of the PCR is 22% in infants younger than 1 month and 97% after 1 month of age. 37 Maternal antibodies may persist in the infant for 13 to 18 months and are not useful for diagnosis. Following liver transaminase levels may help monitor the course of hepatic inflammation.

HERPES SIMPLEX (TYPES 1 AND 2) INFECTION

Prevention

The key to preventing herpes simplex is avoiding exposure. Mothers with active lesions or prodrome should have a cesarean section preferably within 4 to 6 hours of membrane rupture. Treatment with acyclovir should begin at the first sign of neonatal disease or when infants have been exposed to an active lesion.4,5

Communication is necessary between obstetric and neonatal staff to determine the status of a family with a history of herpes. Unnecessary restrictions should not be placed on postpartum mothers who are not actively infected. 5 Health professionals should employ all family-centered strategies used in their institutions with families unless such strategies are precluded by the need for the infant’s treatment.

Data Collection

History

Disease caused by type 1 herpes simplex usually is spread by the oral route, whereas disease caused by type 2 herpes simplex is usually spread by the genital route. 4Many mothers who transmit herpes simplex to their newborn infants are asymptomatic.68 The risk to the infant from recurrent lesions is minimal. 4,46

Signs and Symptoms

Laboratory Data

A cytologic examination of the base of skin vesicles with a Giemsa stain (Tzanck test) may reveal characteristic but nonspecific giant cells and eosinophilic intranuclear inclusions. The virus may be readily identified on a tissue culture within 48 hours from the respiratory and genital tracts, blood, urine, and CSF. 82 Rapid viral diagnosis by direct fluorescent antibody tests is widely available. 4 Detection of virus in CSF by PCR assay is preferred, if available. 19 Although tests of paired serology such as complement fixation (CF) test, ELISA, and neutralization are available, they are of little value in an acute clinical situation. 4 Elevated liver transaminases and thrombocytopenia may indicate herpes infection. 16

Treatment

Table 22-1 outlines the treatment of herpes simplex infection.

Parent Teaching

Families with herpes simplex require consistent and detailed teaching about prevention of transmission of herpes to the infant. Breast-feeding mothers can be reassured that they may continue to breast feed as long as no lesions are on their breasts. Emphasis should be placed on the need for breast-feeding mothers to check their breasts for lesions.5

Parents with active herpes simplex should employ good handwashing technique while caring for their infants. Parents with oral herpes should avoid kissing their infants while lesions are open and draining. 4

LISTERIA MONOCYTOGENES INFECTION

Prevention

Data Collection

Treatment

Table 22-1 outlines the treatment of Listeria monocytogenes infection.

Parent Teaching

See the section on bacterial infections and bacterial sepsis on pp. 571-572 and 575.

MYCOBACTERIUM TUBERCULOSIS INFECTION

Prevention

Mothers at risk for Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection may be identified with a tuberculin test during pregnancy. If the mother is a tuberculin converter (has had a positive skin test result within the past 2 years), a radiographic examination of the chest and lungs should be performed. If the mother has active tuberculosis, she should be treated with isoniazid plus rifampin and ethambutol for at least 9 months. Safety of pyrazinamide in pregnancy is not well established, and this drug is not used routinely in pregnant women. Pyridoxine (vitamin B 6) always should be given with isoniazid during pregnancy and breast feeding because of the increased requirements for this vitamin. If the mother does not have active tuberculosis, household contacts should be screened. If the disease is identified in the mother or household contacts, the infant is at high risk for developing tuberculosis. 4

Separate infants of mothers with active disease from the mother until the mother is not contagious (usually negative sputum). Treat high-risk infants with isoniazid (10 mg/kg/day) or a tuberculosis vaccine (Calmette-Guérin bacillus) (see Table 22-3). 4,5

Data Collection

History

A strong history of maternal contact with tuberculosis favors the diagnosis. This is especially true in high-risk populations (Southeast Asians, American Indians, and families with a known cavitary disease). Mothers with HIV infection are at an increased risk for developing active tuberculosis. 4,112

Signs and Symptoms

Mothers may be relatively asymptomatic or have signs and symptoms that are generalized (fever and weight loss) or localized to the respiratory tract. 4 A congenital infection is extremely rare. 5Nonspecific signs and symptoms such as failure to thrive and unexplained hypothermia or hyperthermia are the most common manifestations in the neonatal period.

Laboratory Data

Acid-fast organisms found on smears of gastric aspirates, sputum, CSF, or infected tissues strongly suggest tuberculosis in the neonate. Isolating Mycobacterium tuberculosis by culture is diagnostic and should be sought aggressively. The tuberculin test result usually is positive (>10-mm induration) in active tuberculosis. However, a positive skin test result requires 3 to 12 weeks after infection to manifest itself, and the test result usually is negative in a neonate. A chest radiograph examination also usually yields a negative result in a neonate. 4

Treatment

Because congenital tuberculosis is such a rare condition, optimal therapy has not been established. However, most recommendations suggest four-drug therapy (isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and streptomycin or kanamycin). 4

Parent Teaching

Infants who are treated with isoniazid or breast-fed infants whose mothers are treated with isoniazid should receive pyridoxine supplementation. 4

NEISSERIA GONORRHOEAE INFECTION

Prevention

Screening high-risk mothers before delivery may identify asymptomatic gonorrhea. Treating positive mothers before delivery or exposed infants at delivery is necessary. 4

Administering silver nitrate, erythromycin, or tetracycline in the eyes is mandatory in all vaginal deliveries.4

Data Collection

History

Mothers with previous venereal disease are a high-risk group, because 80% of the infected women may be asymptomatic.

Signs and Symptoms

The predominant manifestation of gonorrhea is ophthalmia neonatorum, although a systemic bloodborne infection may rarely occur involving the joints, lungs, endocardium, and CNS. Conjunctivitis usually begins 2 to 5 days after birth. Eye prophylaxis minimizes but does not guarantee freedom from infection. Scalp abscess resulting from fetal monitoring has been reported. 4

Laboratory Data

A Gram stain of purulent eye discharge revealing gram-negative intracellular diplococci is diagnostic. Culture confirmation using fermentation or fluorescence establishes the diagnosis of gonorrhea. The organism is labile, so specimens for culture should be taken to the laboratory and plated immediately. When gonorrhea is diagnosed, other sexually transmitted diseases may be present concomitantly (especially chlamydial infection). 4

Treatment

Table 22-1 outlines the treatment of Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection.

VARICELLA

Prevention

Table 22-2 outlines prevention of infection. 4

Data Collection

History

A history of varicella in the mother before conception virtually excludes the diagnosis. Varicella manifests in the mother with a fever, respiratory symptoms, and characteristic vesicular rash primarily on the trunk. If this occurs within 5 days of delivery, the newborn is at risk for infection. 4 Preventive measures should be instituted as soon as possible. 5 Acute perinatal varicella is frequently a devastating systemic disease. Nosocomially acquired transmission of varicella is a potentially significant problem for high-risk infants: premature infants born to susceptible mothers; infants who are severely premature regardless of maternal status; and immunocompromised patients of all ages (Table 22-4).

| AIDS, Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; D, desirable but optional; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; X, recommended at all times; (X), recommended if soiling is likely or if touching infective materials. | ||||||||

| Recommended Precautions | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease/Organisms | Wash Hands | Private Room or Cohort | Mask | Gown | Glove | Infective Material | Duration of Isolation/Precaution | Comments |

| AIDS/HIV | X | D | No | (X) | (X) | Blood and body fluids | Duration of illness | Utmost care needed to avoid needle sticks |

| Adenovirus | X | X | No | (X) | (X) | Respiratory secretions and feces | Duration of hospitalization | During outbreaks, cohort patients suspected of having adenovirus infection |

| Conjunctivitis | ||||||||

| Gonococcal (ophthalmia neonatorum) | X | X | No | No | (X) | Purulent exudates | Until 24 hr after initiation of effective therapy | |

| Chlamydia | X | No | No | No | (X) | Purulent exudates | Duration of illness | |

| Coxsackievirus | X | D | No | (X) | (X) | Feces and respiratory secretions | For 7 days after onset of illness | |

| Cytomegalovirus | X | No | No | No | (X) | Urine and respiratory secretions | Counsel pregnant personnel | |

| Diarrhea | X | D | No | (X) | (X) | Feces | Duration of illness | Identify colonized or infected infants by culture; institute cohorting |

| Echovirus | X | D | No | (X) | (X) | Feces and respiratory secretions | For 7 days after onset of illness | |

| Gastroenteritis | X | X | No | (X) | (X) | Feces | Duration of illness | |

| Hepatitis—type A | X | D | No | (X) | (X) | Feces | For 7 days after onset of illness | Most contagious before symptoms |

| Hepatitis—type B | X | No | No | (X) | (X) | Blood and body fluids | Duration of positivity | Avoid needle sticks |

| Herpes simplex | X | X | No | (X) | (X) | Lesions, secretions, urine, and stool | Duration of illness | |

| Influenza A or B | X | X | No | (X) | (X) | Respiratory secretions | Duration of illness | Cohort patients suspected of having influenza during outbreak; staff should receive yearly influenza vaccine |

| Meningitis | ||||||||

| Aseptic | X | D | No | (X) | (X) | Feces | Duration of illness | Cohort colonized or infected infants during a nursery outbreak |

| Bacterial | X | No | No | No | No | |||

| Necrotizing enterocolitis | X | No | No | (X) | (X) | (?) Feces | Duration of illness | Cohort ill infants |

| Respiratory syncytial virus | X | X | X | (X) | (X) | Respiratory secretions | Duration of illness | Cohort suspected infants, especially premature infants, during outbreaks |

| Rubella | X | X | X | No | No | Respiratory secretions | Duration of hospitalization | Infants may shed virus for as long as 2 years; seronegative women should avoid contact |

| Staphylococcal disease (Staphylococcus aureus) | X | D | No | (X) | (X) | Purulent exudate | Duration of illness | |

| Streptococcal disease | ||||||||

| Group A | X | D | No | (X) | (X) | Respiratory secretions | 24 hr after initiation of effective therapy | |

| Group B | X | D | No | (X) | (X) | Respiratory and genital secretions | Cohort ill and colonized infants during a nursery outbreak | |

| Syphilis | X | No | No | No | (X) | Lesion secretion and blood | 24 hr after initiation of effective therapy | |

| Toxoplasmosis | X | No | No | No | No | None | ||

| Varicella | X | X | X | X | X | Respiratory and lesion secretions | Until lesions are crusted | Neonates born to mothers with active chickenpox should be placed in isolation precautions at birth; persons who are not susceptible do not need to mask |

| Vancomycin-resistant organisms | X | X | No | X | X | Secretions | Duration of illness | |

Signs and Symptoms

Congenital varicella is rare but has followed maternal varicella in the first trimester of pregnancy. Congenital manifestations include limb atrophy, skin scars, and CNS and eye abnormalities. 4

Laboratory Data

The demonstration of multinucleated giant cells containing intranuclear inclusions in skin scrapings on Giemsa stain is nonspecific but helpful. Virus can be isolated from scrapings of vesicle base during the first 3 to 4 days of the eruption by direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) test, or isolation of virus in tissue culture. 22,25 Isolating the virus from the respiratory tract is difficult. A number of serologic tests such as the fluorescent antibody to membrane antigen (FAMA) test, immune adherence hemagglutination (IAHA) test, ELISA, and neutralization test are available but are not helpful in the acute clinical situation. CF serologic tests are relatively insensitive. 4

EARLY-ONSET BACTERIAL DISEASE

Prevention

For GBS only, see p. 561.

Data Collection

History

Early-onset disease is almost always acquired perinatally and is discussed here. Late-onset disease is discussed in the “Postnatal Acquisition Late-Onset Bacterial Disease” section. Early-onset disease presents as a fulminant multisystem illness during the first days of life (<72 hours of age). Significant risk factors for early-onset disease include prematurity, low birth weight, premature onset of labor, rupture of membranes more than 18 hours, maternal intrapartum temperature higher than 37.5° C, and chorioamnionitis. 90 Bacteria responsible for early-onset disease are acquired from the birth canal before or during delivery and are listed in the Critical Findings box above. Although the advent of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis for GBS infections has generally reduced early-onset disease of this pathogen, it has not been universally experienced and black preterm infants remain at considerably greater risk than do white preterm infants and both black and white term infants. 21

Also, since the practice of intrapartum prophylaxis began, a predominance of gram-negative organisms has been noted in infants weighing less than 1500 grams at birth, and concern for this continued trend remains. 9,107Gram-negative infections now account for more than half of the instances of early-onset sepsis.108,110 Data from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Neonatal Research Network, which comprises 16 major neonatal units, showed an increase in Escherichia coli (E. coli) infections in very-low-birth-weight (VLBW) infants during the period 1998 to 2000 compared with 1991 to 1993 that persisted during the 2002-2003 period. 110 Data from the Norwegian National Cohort demonstrated that in infants born at less than 28 weeks gestational age and with birth weight less than 1000 g, E. coli was the most common organism isolated on the first day of life. 97 Early-onset bacterial disease is associated with a high mortality and significant morbidity. 102,107,108

Organisms Causing Early-Onset Bacterial Sepsis

Common Organisms

Group B Streptococcus

Escherichia coli

Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus

Unusual Organisms

Staphylococcus aureus

Neisseria meningitidis

Streptococcus pneumoniae

Haemophilus influenzae (type B and nontypable)

Rare Organisms

Klebsiella pneumoniae

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Enterobacter species

Serratia marcescens

Group A Streptococcus

Anaerobic species

Signs and Symptoms

Neonatal bacterial sepsis is characterized by systemic signs of infection associated with bacteremia. Meningitis in a neonate can be a sequela of bacteremia. In addition, bloodborne bacteria may localize in other tissues, causing focal disease. Both patterns of bacterial disease, early onset and late onset, have been associated with systemic infections during the neonatal period. 4,94

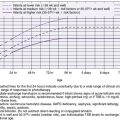

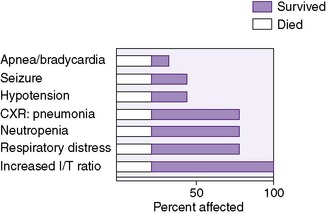

In general, signs, particularly in early-onset disease, are nonspecific and nonlocalizing. Signs and symptoms may include temperature instability (hypothermia or hyperthermia), respiratory distress (apnea, cyanosis, and tachypnea), lethargy, feeding abnormalities (vomiting, increased residuals, and abdominal distention), jaundice (particularly increased direct fraction), seizures, or purpura (Figure 22-1). 94

|

| FIGURE 22-1

(From Nelson SN, Merenstein GB, Pierce JR: Early onset group B streptococcal disease, J Perinatol 6:234, 1986.)

|

Newborn Scale of Sepsis (SOS) is an objective, reliable, and validated scoring tool for the assessment of neonatal infection. By using both clinical indicators (e.g., color, perfusion, muscle tone, response to pain, respiratory distress and rate, temperature,and apnea) and laboratory findings (e.g., white blood cell count [WBC], ratio of immature to total neutrophils [I:T ratio], platelet count, pH, and absolute neutrophil count), the health care provider assigns a score for each parameter. A score less than 10 indicates that the newborn does not have sepsis—a negative predictive value of 97%. The SOS (see Resource Materials for Professionals and Parents on p. 580) awaits testing in a large cohort of neonates.

Laboratory Data

Isolating bacteria from a nonpermissive site (blood, CSF, urine, closed body space) is the most valid method of establishing the diagnosis of bacterial sepsis.127 Surface cultures (including ear and gastric aspirates) do not establish the presence of active systemic infection but merely indicate colonization. Bacterial antigens or endotoxins may be demonstrated in sera, CSF, urine, or body fluids by a variety of methods (counterimmunoelectrophoresis [CIE], latex agglutination [LA], and limulus lysate test). Such a demonstration is not totally definitive, nor does it allow the determination of the antibiotic sensitivity of the offending organism. 94 False-positive reactions may be caused by skin surface contamination or gastrointestinal absorption of antigen. 8The CSF is examined in most infants suspected of sepsis, because meningitis is a frequent manifestation of sepsis in neonates, especially in symptomatic infants and infants with GBS sepsis and with late-onset disease (Table 22-5). It has been suggested that, because of the low yield and potential adverse effects from lumbar puncture, examination of CSF be deferred in asymptomatic infants being evaluated for maternal risk factors or respiratory distress. 43,59,94,103,123The CSF is examined in most infants suspected of sepsis, because meningitis is difficult to exclude without a lumbar puncture and its diagnosis affects therapy and follow-up in a neonate.94,107

| *Modified from Remington JS, Klein JO, editors: Infectious diseases of the fetus and newborn infant, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2001, Saunders. See also Mhanna MJ, Alessah H, Gori A, et al: Cerebrospinal fluid values in very low birth weight infants with suspected sepsis at different ages, Pediatr Crit Care Med 9:294, 2008. |

||||

| White Blood Cells | Polymorphonuclear Neutrophils | Protein (mg/dL) | Glucose (mg/dL) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PREMATURE INFANTS | ||||

| Reported means | 2-27 | 75-150 | 79-83 | |

| Reported ranges | 0-112 | 31-292 | 64-106 | |

| TERM INFANTS | ||||

| Reported means | 3-5 | 2-3 | 47-67 | 51-55 |

| Reported ranges | 0-90 | 0-70 | 17-240 | 32-78 |

Several laboratory aids are used in assessing neonatal sepsis, but it must be realized that these tests are not sensitive or specific enough to influence clinical decisions on their own. 4,28,38Leukocyte indices predict sepsis with sensitivities ranging from 17% to 90% and specificities from 31% to 100%. 28C-reactive protein (CRP) is an acute-phase reactant synthesized in the liver in the first 6 to 8 hours of the infective process with a low sensitivity (60%) early in sepsis. However, serial CRP measurements at 24 and 48 hours improve sensitivity to 82% and 84% and specificity and positive predictive value range from 83% to 100%. 84 Negative predictive values for CRP are extremely high. Serial CRP patterns have been found to be useful to follow resolution of infection and guide antibiotic therapy. 35,45,64,120,124 CRP levels do not seem to be affected by gestational age and have better sensitivity and negative predictive values when compared with leukocyte indices. 30,124 CRP response has been found to be better in gram-negative infections when compared with infections with coagulase-negative Staphylococcus (CoNS). 92,96Procalcitonin, another acute-phase reactant, which rises within 4 hours of exposure to bacterial endotoxin, has a sensitivity and specificity ranging from 83% to 100%. The serum profile of procalcitonin has been claimed to be superior to that of CRP in the diagnosis of sepsis, after resolution of infection, and may differentiate between sepsis and other inflammatory processes (e.g., trauma). 7,70,117

Evaluation of a composite set of markers (e.g., CRP and interleukin-6 [IL-6] 86; CRP and leukocyte indices51) involving acute phase reactants, leukocytes, and cytokines/chemokines may increase sensitivity and specificity in the diagnosis of sepsis. Serial measurements may be more useful, as is a combination of tests. 84 Radiographic examination of the chest and other specific areas indicated by clinical concerns may also be helpful. 94

Several other nonspecific laboratory abnormalities may accompany neonatal sepsis, including hyperglycemia, hypoglycemia, and unexplained metabolic acidosis. Molecular techniques for diagnosis of infection are fast and reliable and may be very useful, especially in infants whose mothers have received intrapartum antibiotics. In a study of 548 paired neonatal blood samples that compared the utility of PCR for the bacterial 16S rRNA gene with that of microbial culture by BACTEC 9240 instrument, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive values, and negative predictive values were 96.0%, 99.4%, 88.9%, and 99.8%, respectively. This required a 9-hour turnaround time with blood volumes as little as 200 mcL. 61 Real-time PCR assay targeting the highly conserved 380 bases of 16S rDNA requires less than 4 hours with excellent agreement with blood culture results. 62 PCR with microarray hybridization not only detects bacteremia but also can identify the infecting organism rapidly and reliably. 104 It may be that using PCR assays with microarray hybridization will become the future for diagnosing bacteremia in an accurate and rapid way.

Treatment

Antibiotics are the cornerstone of the treatment for presumed or confirmed infections in neonates. The indiscriminate or inappropriate use of systemic antibiotics may cause undesirable side effects, favor the emergence of resistant strains of bacteria, and alter the normal flora of the newborn. 20 Adequate and appropriate specimens for culture should be obtained before antibiotic therapy is initiated. Emergence of antibiotic resistance in gram-negative organisms is a major clinical concern. 10 In the data from the NICHD Neonatal Research Network, 85% and 75% of early-onset E. coli infections were ampicillin resistant in the 1998-2000 and the 2002-2003 cohorts, respectively. 108,110 Plasmid-mediated extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs) (produced by Klebsiella spp., E. coli, and Serratia) that confer resistance to a variety of β-lactam agents (penicillins and cephalosporins) and chromosomally mediated AmP-C–type β-lactamase ( Enterobacter and Citrobacter spp.)–producing gram-negative organisms have been isolated from the NICU. 54,55,89 Exposure to third-generation cephalosporins (e.g., cefotaxime) and being a VLBW infant are noted risk factors for the acquisition of resistant organisms.

Broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage, usually with ampicillin and an aminoglycoside for early-onset sepsis, is commonly initiated pending culture and sensitivity results. Once causative organisms are identified and antibiotic sensitivities established, the most appropriate and least toxic antibiotic or antibiotic combination should be continued for an appropriate period by a suitable route. If adequate cultures are negative after a reasonable period (24 to 48 hours), antibiotic therapy may be discontinued in most situations.

Antibiotics are not the entire solution to treating the infected newborn. 42,47 Meticulous attention to the treatment of associated conditions, such as shock, hypoxemia, thermal abnormalities, electrolyte or acid-base imbalance, inadequate nutrition, anemia, or presence of pus or foreign bodies, may be as important as choosing the proper antibiotic. Further investigation is necessary before newer adjunctive therapies such as IV immunoglobulin and non-antibiotic therapies or preventive regimens can be recommended. 56,80,86,122Table 22-1 provides guidelines for choosing the proper antibiotic for indicated conditions; Table 22-6 gives the proper dose, route, and frequency of administration of commonly used antibiotics in the newborn nursery. Table 22-7 describes the passage of antibiotics across the placenta, and Table 22-8 describes their passage into breast milk.

| CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; IM, intramuscularly; IV, intravenously; PO, orally. | |||

| *Pharmacokinetics in newborns not well characterized. These drugs should be used with extra caution in neonates (pediatric infectious disease consultation recommended). |

|||

| †Antiviral agent. |

|||

| ‡Antifungal agent. |

|||

| Antibiotic, Antiviral, or Antifungal | Daily Dosages and Intervals | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Route | 0 to 7 days of age | More than 7 Days of Age | |

| Acyclovir† | IV | 20 mg/kg/dose q 8-12 hr depending on gestation and age | Same |

| Amikacin sulfate | IV, IM | 7.5-10 mg/kg/dose q 12 hr depending on gestation and age | Same |

| Amoxicillin | PO | 50 mg/kg/day divided q 12 hr | 50 mg/kg/day divided q 8 hr |

| Amoxicillin/Clavulanic acid | PO | Not recommended | 30 mg/kg/day divided q 12 hr |

| Ampicillin | |||

| Meningitis | IV | 100 mg/kg/day divided q 12 hr | 150-200 mg/kg/day divided q 6-8 hr |

| Other indications | IV, IM, PO | 50 mg/kg/day divided q 12 hr | 75 mg/kg/day divided q 8 hr |

| Azithromycin | IV, PO | 5 mg/kg/day q 24 hr | 10 mg/kg/day q 24 hr |

| Cefazolin* | IV, IM | 50 mg/kg/day divided q 12 hr | 50-75 mg/kg/day divided q 8-12 hr |

| Cefotaxime | IV, IM | 100 mg/kg/day divided q 12 hr | 150 mg/kg/day divided q 8 hr |

| Ceftazidime* | IV | 100 mg/kg/day divided q 12 hr | 150 mg/kg/day divided q 8 hr |

| Clindamycin | IV, PO | 10-15 mg/kg/day divided q 8-12 hr | 15-20 mg/kg/day divided q 6-8 hr |

| Erythromycin ethyl succinate (EES) | PO | 20 mg/kg/day divided q 12 hr | 30-40 mg/kg/day divided q 8 hr |

| Ganciclovir† | IV | 6 mg/kg/dose q 12-24 hr depending on gestation and age | |

| Gentamicin | IV, IM | 2.5 mg/kg/dose q 8-24 hr depending on gestation and age | Same |

| Meropenem* | IV | 40 mg/kg/day divided q 12 hr | 60 mg/kg/day divided q 8 hr (higher doses may be needed in meningitis) |

| Metronidazole | IV, PO | 7.5-15 mg/kg/day divided q 12-24 hr | 15-30 mg/kg/day divided q 12 hr |

| Nafcillin | IV | 50-75 mg/kg/day divided q 8-12 hr | 75-150 mg/kg/day divided q 6-8 hr |

| Nystatin‡ | PO | 400,000 units/day divided q 6 hr | Same |

| Penicillin G | |||

| Meningitis | IV | 100,000-150,000 units/kg/day divided q 8-12 hr | 200,000-225,000 units/kg/day divided q 6-8 hr |

| Other indications | IV | 50,000 units/kg/day divided q 12 hr | 75,000 units/kg/day divided q 6-8 hr |

| Penicillin G, benzathine | IM | 50,000 units/kg (1 dose only) | Same |

| Penicillin G, procaine | IM | 50,000 units/kg/day once daily | Same |

| Pentamidine isethionate* | IV | 4 mg/kg/day for 14 days (available from CDC, Atlanta, Georgia) | Same |

| Piperacillin/Tazobactam | IV | 100-200 mg/kg/day divided q 12 hr | 300 mg/kg/day divided q 8 hr |

| Rifampin | IV, PO | 10 mg/kg/day q 24 hr | Same |

| Ticarcillin | IV, IM | 150-225 mg/kg/day divided q 8-12 hr | 225-300 mg/kg/day divided q 6-8 hr |

| Tobramycin | IV, IM | 2.5 mg/kg/dose q 12-24 hr depending on gestation and age | 2.5 mg/kg/dose q 8-18 hr |

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX) | IV, PO | 10-20 mg/kg/day TMP and 50-100 mg/kg/day SMX | Same |

| Vancomycin | IV | 15 mg/kg/dose q 12-24 hr depending on gestation and age | 15 mg/kg/dose q 8-18 hr depending on gestation and age |

| Zidovudine† | IV | 1.5 mg/kg/dose q 6-12 hr depending on gestation and age | Same |

| PO | 2 mg/kg/dose q 6-12 hr depending on gestation and age | Same | |

| *Several factors determine the degree of transfer of antibiotics across the placenta, including lipid solubility, degree of ionization, molecular weight, protein binding, placental maturation, and placental and fetal blood flow. |

|

| Percentage of Antibiotic in Indicated Category | Antibiotic |

|---|---|

| Equal to serum concentration |

Amoxicillin

Ampicillin

Carbenicillin

Chloramphenicol

Methicillin

Nitrofurantoin

Penicillin G

Sulfonamides

|

| 50% of serum concentration | Aminoglycosides |

| 10%-15% of serum concentration |

Amikacin

Cephalosporins

Clindamycin

Nafcillin

Tobramycin

|

| Negligible (<10% of serum concentration) |

Dicloxacillin

Erythromycin

|

| *Data on concentrations of antibiotics in human breast milk are sparse. Because most antibiotics are present in breast milk in microgram amounts, they are normally not ingested by the infant in therapeutic amounts. |

|

| Percentage of Antibiotic in Indicated Category | Antibiotic |

|---|---|

| Equal to serum concentration |

Isoniazid

Metronidazole

Sulfonamides

Trimethoprim

|

| 50% of serum concentration |

Chloramphenicol

Erythromycin

Tetracyclines

|

| <25% of serum concentration |

Cefazolin

Kanamycin

Nitrofurantoin

Oxacillin

Penicillin G

Penicillin V

|

Parent Teaching

Transplacental infection often results in fetal abnormality or death. Newborns who survive may have long-term sequelae such as developmental, neurologic, motor, sensory, growth, and physical abnormalities.

Before antibiotic use, the mortality from bacterial sepsis was 95% to 100%, but antibiotics and supportive care have reduced the mortality rate to less than 50%, but survival is highly variable and depends on the organism and underlying or associated conditions. Debilitated infants (preterm and sick neonates) are at greater risk and have a higher incidence of morbidity and mortality than term healthy neonates. The most common complications of bacterial sepsis are meningitis and septic shock. The outcome is influenced by early recognition and vigorous treatment with appropriate antibiotics and supportive care.

POSTNATAL ACQUISITION LATE-ONSET BACTERIAL DISEASE

Prevention

The CDC defines nosocomial as all neonatal infections acquired in the intrapartum period or during hospitalization. Infants requiring the specialized care of NICUs are highly susceptible to infections. Prematurity, stress, immature immune systems, and complicated medical and surgical problems contribute to their increased susceptibility. In addition, most infants in the NICU require a variety of invasive diagnostic, therapeutic, and monitoring procedures; many of these procedures bypass natural physical barriers, which may allow colonization to occur and a nosocomial (late-onset) infection to develop. 48

Infection control principles and practices for the prevention of these nosocomial infections are outlined in Table 22-9. Table 22-4 outlines infection control measures and isolation techniques for specific diseases. 4,13,49,105

| NICU, Neonatal intensive care unit. | |

| Principle | Practice |

|---|---|

| HANDWASHING | |

| Handwashing is the most important procedure for controlling infection in the NICU. |

1. Before each shift, wash hands, wrists, forearms, and elbows with antiseptic. Scrub hands with a brush or pad for 2-3 min and rinse thoroughly. Chlorhexidine, hexachlorophene, and iodophors are the preferred products.

2. Wash hands for 10-15 sec between infant contacts. Soap and water are adequate unless the infant is infected or contaminated objects have been handled.

3. Use an antiseptic for handwashing before surgical or similar invasive procedures.

4. Alcohol-based disinfectants are increasingly employed and are effective when used before and after patient contact.

|

| PATIENT PLACEMENT | |

| Overcrowding in the NICU increases risk for cross-contamination. |

1. Provide 4- to 6-ft intervals between infants.

|

| SKIN AND CORD CARE | |

| The skin, its secretions, and its normal flora are natural defense mechanisms that protect against invading pathogens (see Chapter 19) |

1. The American Academy of Pediatrics suggests using a dry technique:

a. Delay initial cleansing until temperature is stable. Manipulating an infant’s skin must be minimized.

b. Use sterile cotton sponges and sterile water or mild soap to remove blood from face and perineal area.

c. Do not touch other areas unless they are grossly soiled.

|

| No single method of cord care has been identified to prevent colonization or limit disease. |

2. Local application of alcohol, triple dye, and various antimicrobial is currently used.

|

| MEDICAL DEVICES | |

| Medical devices facilitate infections by the following:

1. Bypassing normal defense mechanisms, providing direct access to blood and deep tissues

2. Supporting growth of microorganisms and becoming reservoirs from which bacteria can be transmitted with the device to another patient

|

1. Intravenous (IV) infusion devices predispose infants to phlebitis and bacteremia. Preventive measures include preparing the site with tincture of iodine (2% iodine in 70% alcohol), an iodophor, or 70% alcohol; anchoring the IV securely; performing site assessment and care every 24 hr (routine site care is not necessary with polyurethane dressing); rotating the IV site every 48-72 hr; changing the IV tubing every 24-48 hr on regular IVs; and discontinuing the IV at the first sign of complication.

|

|

3. Providing a “protected site” when placed in deeper tissue, so phagocytosis or defense mechanisms cannot eradicate the organisms

4. Using sterile medical devices that are occasionally contaminated from the manufacturer or central supply

|

2. Arterial lines predispose infants to bacteremia. Preventive measures include aseptically inserting the catheter using gloves, inspecting the site and performing site care every 24 hr, treating the catheter and stopcocks as sterile fields, and minimizing manipulation by drawing all blood specimens at the same time.

3. Intravascular pressure–monitoring systems predispose infants to septicemia. Preventive measures include replacing the flush solution every 24 hr, replacing the chamber dome, and replacing the tubing and continuous flow device (if used) at 48-hr intervals and between each patient.

4. Respiratory therapy devices increase the risk for contamination. Preventive measures include using aseptic technique during suctioning; dating opened solution for irrigation, humidification, and nebulization, and discarding after 24 hr; ensuring routine replacement and cleaning of all respiratory equipment, including Ambu bags, cascade nebulizers, endotracheal tube adaptors, and tubing; and checking sputum cultures and Gram stains every several days to assess the degree of colonization or infection in the intubated patient.

|

| SPECIMEN COLLECTION | |

| Improperly collected specimens cause infection at the site of collection or erroneous diagnosis, leading to the administration of the wrong antibiotic or delayed administration of the appropriate antibiotic. |

1. Wash hands before collecting specimen.

2. Observe aseptic technique to reduce risk for infection and to avoid contamination of specimen.

3. Deliver specimens to the laboratory immediately.

4. Do not use femoral sticks.

|

| NURSERY ATTIRE | |

| Personal clothing and unscrubbed skin areas of personnel should not touch infants. |

1. Short-sleeved scrub gowns accommodate washing elbows.

2. Long-sleeved gowns should be worn and changed between handling of infected or potentially infected infants.

3. Sterile gowns are necessary for sterile procedures.

|

| EMPLOYEE HEALTH | |

| Transmission of disease among patients and employees can occur bidirectionally. Each NICU must establish reasonable guidelines for restriction of assignments based on the employee’s potential to transmit disease and the potential risk for acquiring disease. |

1. Conditions that commonly restrict personnel from patient care in the NICU are skin lesions and draining wounds, acute respiratory infections, fever, gastroenteritis, active herpes simplex (oral, genital, or paronychial), and herpes zoster.

2. Conditions that are transmitted from infants to personnel are the following:

a. Rubella: Obtain rubella titers from women of childbearing age; if a protective level is not present, they should be vaccinated.

b. Cytomegalovirus is a potential threat to pregnant women. Adherence to good infection control practices may reduce this threat.

c. Hepatitis B is usually not a major problem in the NICU, because host vaccine is available and may be considered for high-risk individuals (see Tables 22-2 and 22-3).

d. Use of gloves with body fluid contact will decrease the risk for transmission of hepatitis B virus and human immunodeficiency virus.

|

| COHORTING | |

| Cohorting is an important infection control measure used primarily during outbreaks or epidemics in the NICU. The object of cohorting is to limit the number of contacts of one infant with other infants and personnel. |

1. Group together infants born within the same time frame (usually 24-48 hr) or who are colonized or infected with the same pathogen. These infants should remain together until discharged.

2. Provide nursing care by personnel who do not care for other infants.

3. After all infants in cohort are discharged, clean the room before admittance of a new group of infants.

|

Data Collection

History

Late-onset disease may occur as early as 3 days of age but is more common after the first week of life. Affected infants may have a history of obstetric complications, but they are less common than obstetric complications in early-onset disease. Bacteria responsible for late-onset sepsis and meningitis include those acquired from the maternal genital tract and organisms acquired after birth from human contact or from contaminated equipment or material (see the Critical Findings box above). 5 Gram-positive organisms predominate in late-onset sepsis, and gram-negative organisms account for about one third of late-onset cases of sepsis in VLBW infants. 109 Although prematurity remains the most significant factor, invasive procedures performed on a neonate, such as intubation, catheterization, and surgery, also increase the risk for bacterial infection. 47,71,109

Signs and Symptoms

Similar to those of early-onset sepsis, they are nonspecific.

Treatment

Broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage, usually vancomycin and an aminoglycoside or a third-generation cephalosporin, is commonly initiated pending culture and sensitivity results. However, vancomycin resistance remains a potential problem in the care of sick neonates. 20,52,100 To minimize the development of these resistant organisms, the CDC has recommended prudent vancomycin use, education of medical personnel about the problem of vancomycin resistance, early detection and prompt reporting of organisms, and immediate implementation of appropriate infection control measures (see Table 22-4).

FUNGAL INFECTION

Fungal infections have been a significant cause of neonatal morbidity and mortality. They are the second most common infection after 72 hours of life in infants weighing less than 1500 g. 109Candida species are the most common. In addition, they are usually seen in infants with congenital anomalies requiring surgery or infants who require multiple or prolonged vascular catheterization.

Prevention

Because these infants are often colonized at birth, strict adherence to aseptic technique when dealing with central catheters is essential. Antibiotic use should be minimized and limited to treatment of specific illnesses.

Data Collection

History

Prematurity (<32 weeks’ gestation), Apgar score less than 5 at 5 minutes, shock, antibiotic therapy, parenteral nutrition for longer than 5 days, use of lipids for longer than 7 days, presence of a central catheter, length of stay in hospital longer than 7 days, use of histamine-2 (H 2) blockers, and intubation are risk factors for fungal infections. 101

Signs and Symptoms

Signs and symptoms may be nonspecific, nonlocalizing, and difficult to differentiate from those of bacterial sepsis. Skin infections in high-risk infants, especially in VLBW infants, can become invasive and should be treated. 27

Laboratory Data