85

Infantile Hemangiomas and Vascular Malformations

• Vascular anomalies, which often present at birth or during early infancy, are classified into two groups based on their biologic and clinical behavior:

– Vascular malformations that result from defective vascular morphogenesis.

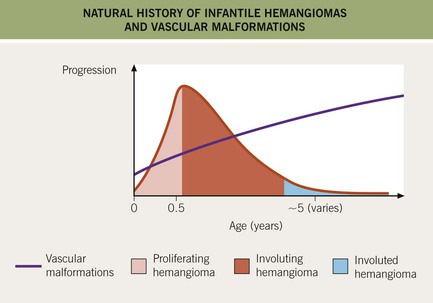

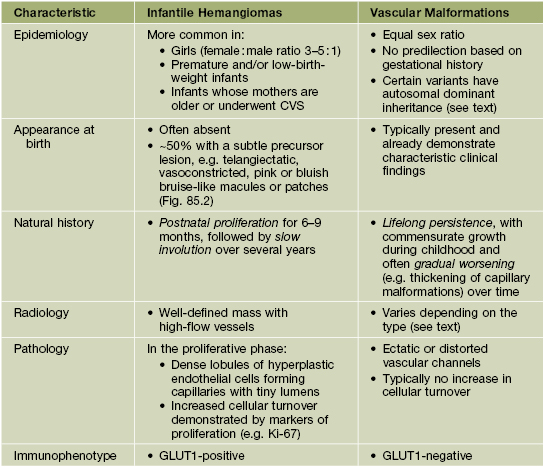

• Features that distinguish IHs from vascular malformations are presented in Table 85.1, and differences in their natural histories are depicted in Fig. 85.1.

Table 85.1

Comparison of infantile hemangiomas with vascular malformations.

CVS, chorionic villus sampling; GLUT1, glucose transporter protein-1 (expressed by the placenta as well as infantile hemangiomas, but no diffuse expression in other vascular tumors).

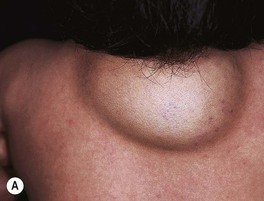

Fig. 85.2 Hemangioma precursors. These initial lesions can have a ‘bruised’ (A) or blanched (B) appearance. A, Courtesy, Maria Garzon, MD; B, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

• Additional vascular neoplasms are discussed in Chapter 94; other vascular ectasias, such as telangiectasias and angiokeratomas, are covered in Chapter 87.

Infantile Hemangioma (IH)

• Benign vascular neoplasm that represents the most common tumor of infancy.

– Affects ~5% of infants, with a predilection for girls and premature neonates (see Table 85.1).

• IHs appear during the first few weeks of life, with a characteristic course:

– Subsequent involution gradually over several years (e.g. 30% completed by 3 years of age and 50% by 5 years), with softening and a duller or lighter color followed by flattening (Fig. 85.3).

Fig. 85.3 Involuting infantile hemangioma. Note the duller red to grayish color with areas of complete fading. These color changes were accompanied by gradual softening and flattening.

– Some IHs involute with little or no visible sequelae, whereas others (especially pedunculated or exophytic lesions) leave atrophic, fibrofatty, or telangiectatic residua in addition to scars at sites of previous ulceration (discussed later; Fig. 85.4).

Fig. 85.4 Residua of infantile hemangiomas. A Superficial hemangioma with a healing ulcer in an infant. B Hypopigmentation (arrows) and a circular scar at the site of the previous ulcer in the same patient 20 years later. C, D Residual telangiectasias. E Atrophy and fibrofatty changes. A, B, E, Courtesy, Ronald P. Rapini, MD; D, Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

• Divided into three clinical subtypes based on the depth of cutaneous involvement:

– Superficial lesions (~50%; upper dermis) are bright red with a finely lobulated surface (‘strawberry’ hemangiomas) during proliferation, changing to a mixture of purple-red and gray during involution (Fig. 85.5).

Fig. 85.5 Superficial infantile hemangiomas. Note the bright red color and finely lobulated surface. Involvement may be diffuse or broken up. Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

– Deep lesions (~15%; lower dermis and subcutis) present as warm, ill-defined, light blue-purple, rubbery nodules or masses (Fig. 85.6); often become evident later and proliferate ~1 month longer than superficial lesions.

Fig. 85.6 Deep infantile hemangiomas. Note the skin-colored to bluish hue with scattered telangiectasias. A, Courtesy, Anthony J. Mancini, MD.

• IHs have two major distribution patterns:

– Focal lesions arise from a localized nidus (see Fig. 85.5A).

– Segmental lesions cover a broader area or developmental unit and are more likely to be associated with regional extracutaneous abnormalities – e.g. PHACE(S) and LUMBAR syndromes (discussed later) (Fig. 85.7).

Fig. 85.7 Segmental infantile hemangiomas. A Segmental facial hemangioma mimicking a capillary malformation. B Thicker segmental facial hemangioma partially obstructing the visual axis. Both of these patients had PHACE(S) syndrome. C Segmental lumbosacral hemangioma. This child is at risk for LUMBAR syndrome. A, Courtesy, Maria Garzon, MD; B, C, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

• DDx: precursors and early lesions: capillary malformation, telangiectasias; well-developed lesions: pyogenic granuloma, other vascular tumors, venous/lymphatic malformation, and rare entities such as nasal glioma and soft tissue sarcomas (see Table 53.1); multiple lesions: glomuvenous malformations, blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome, multifocal lymphangioendotheliomatosis with thrombocytopenia, ‘blueberry muffin baby’ (see Chapter 99).

Complications of IHs

• Ulceration: occurs in ~10% of lesions, especially those on the lip and in the anogenital region or other skin folds, at a median age of 4 months (Fig. 85.8); whitish discoloration of an IH in an infant <3 months of age may signal impending ulceration; results in pain, a risk of infection (relatively uncommon), and eventual scarring (see Fig. 85.4A,B).

Fig. 85.8 Ulcerated infantile hemangiomas. A Ulcerated hemangioma on the buttock. Because the hemangioma component may not be obvious, this diagnosis should be considered when an infant presents with an ulcer in the diaper area. B Ulcerated superficial hemangioma above the ear. Note the distortion of the pinna. Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

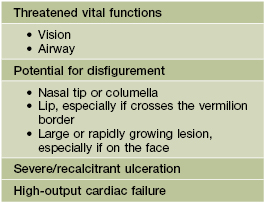

• Disfigurement and interference with function due to the IH’s location and/or large size.

– Periocular IH – risk of astigmatism if puts pressure on globe, amblyopia if obstructs the visual axis, and strabismus if affects orbital musculature (see Fig. 85.7A,B); requires ophthalmologic evaluation.

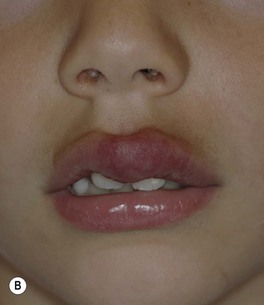

– IH on nasal tip, columella, or lip (especially if crosses the vermilion border) – high risk of distortion of facial structures (as well as ulceration if on the lip) (Fig. 85.9).

Fig. 85.9 Infantile hemangioma on the lip. This is a cosmetically sensitive site, especially when lesions cross the vermilion border, and hemangiomas in this location are prone to ulceration. Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

– IH on breast (in girls) – may affect underlying breast bud, so early surgery should be avoided.

• Associated extracutaneous abnormalities.

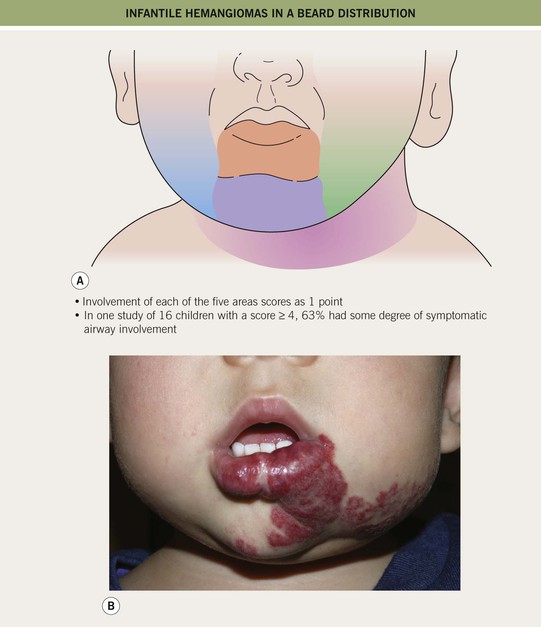

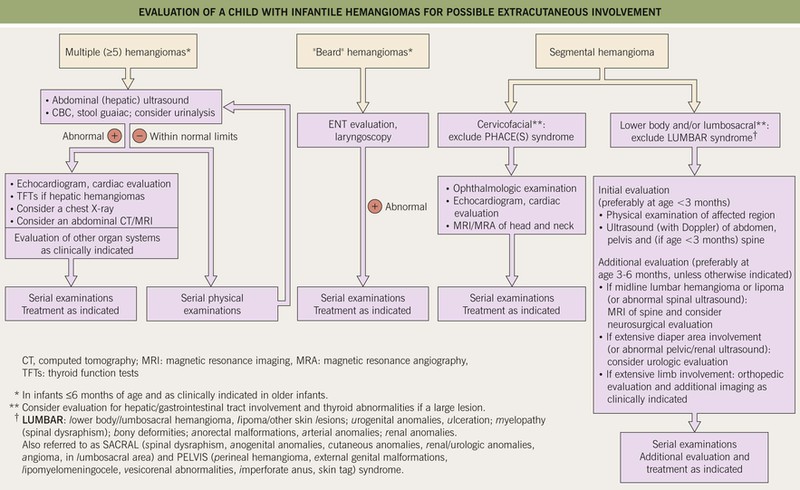

– IHs in ‘beard’ area of the lower face – often associated with airway IHs, which may present with noisy breathing or biphasic stridor; otolaryngologic evaluation is needed for infants with symptoms or when the IH is likely to be actively proliferating (i.e. <4–5 months of age) (Fig. 85.10).

Fig. 85.10 Infantile hemangiomas in a ‘beard’ distribution. A Anatomic sites associated with risk of an airway hemangioma. B Infant with a laryngeal hemangioma in addition to cutaneous lesions in a ‘beard’ distribution. A, Adapted with permission from Orlow SJ, Isakoff MS, Blei F. Increased risk of symptomatic hemangiomas of the airway in association with cutaneous hemangiomas in a ‘beard’ distribution. J. Pediatr. 1997;131:643–646; B, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

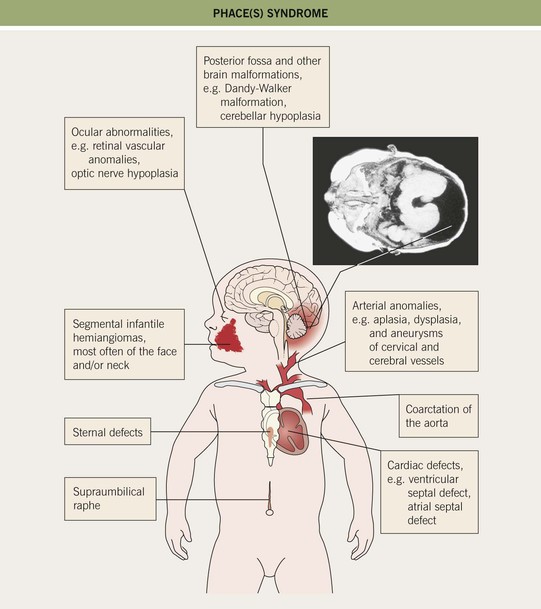

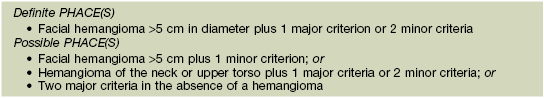

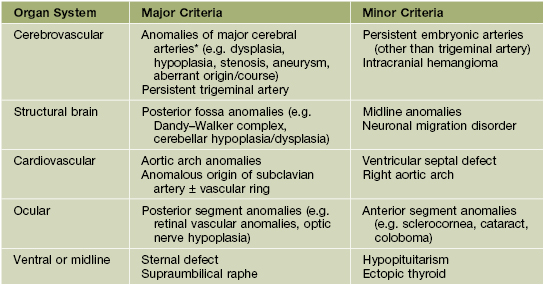

– Large facial IHs, particularly segmental lesions – risk of PHACE(S) syndrome: P, posterior fossa malformations; H, hemangioma; A, arterial abnormalities (cervical, cerebral); C, cardiac defects, especially coarctation of the aorta; E, eye anomalies; S, sternal defects and supraumbilical raphe (Table 85.2; Figs. 85.11 and 85.12; see Fig. 85.7A,B).

Table 85.2

Diagnostic criteria for PHACE(S) syndrome.

* Major cerebral arteries include internal carotid artery; middle, anterior, or posterior cerebral artery; and vertebrobasilar system.

Fig. 85.12 Evaluation of a child with infantile hemangiomas for possible extracutaneous involvement. See Fig. 85.11 and Table 85.2 for additional information on PHACE(S) syndrome.

– Large IHs on the lower body, particularly segmental lesions – risk of LUMBAR syndrome: L, lower body/lumbosacral IH and lipomas; U, urogenital anomalies and ulceration; M, myelopathy (spinal dysraphism); B, bony deformities; A, anorectal and arterial anomalies; R, renal anomalies (see Figs. 85.7C and 85.12).

– Midline lumbosacral IHs – risk of spinal dysraphism (see Chapter 53).

– Multiple (≥5) IHs – may be associated with visceral hemangiomatosis, most often hepatic; the cutaneous IHs are usually relatively small and superficial, but hepatic involvement can be associated with complications such as high-output cardiac failure and hypothyroidism (due to iodothyronine diodinase production by the IH) (Fig. 85.13; see Fig. 85.12).

Treatment of IHs

• Local Rx: topical timolol (systemic absorption possible, especially if ulcerated or involving mucous membranes) or superpotent CS for thin superficial lesions; intralesional CS for thicker lesions (avoiding the periocular area); pulsed dye laser for residual telangiectasias and possibly for thin superficial lesions.

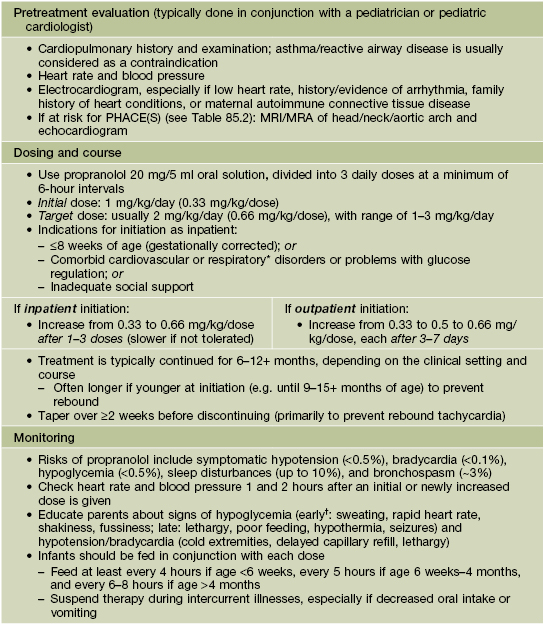

• Systemic Rx: indications are listed in Table 85.3; oral propranolol (Table 85.4) has replaced prednisolone as the first-line systemic therapy.

Table 85.4

Administration of propranolol for infantile hemangiomas: consensus recommendations.

Propranolol, a nonselective β-blocker, binds to β2-adrenergic receptors on hemangioma endothelial cells, with effects including vasoconstriction (leading to softening and dulling of color within 24 hours), decreased expression of pro-angiogenic growth factors, and induction of apoptosis. Practices vary widely, and some pediatric dermatologists and cardiologists recommend more or less intensive evaluation and monitoring. The patient’s age, hemangioma-related issues, and medical comorbidities also affect management.

* Including symptomatic airway hemangiomas.

† May be masked with the β-adrenergic blockade.

Based on Drolet BA, Frommelt PC, Chamlin SL, et al. Pediatrics 2013;131:128–140.

Hemangioma Variants

• IHs with minimal or arrested growth present with reticulated erythema, telangiectasias, and larger ectatic vessels, often on a vasoconstricted background; a proliferative component is either absent or represents <25% of the surface area (often small red papules at the periphery) (Fig. 85.14); histologically, these lesions are GLUT1-positive like classic IHs (see Table 85.1).

Fig. 85.14 Minimal/arrested growth infantile hemangiomas. Telangiectasias and larger ectatic vessels are evident. Note the focal crusting (A) and small bright red papules behind the ear (arrow) (B). The presence of the latter (which may be subtle or absent), reticulated erythema, and characteristic telangiectasias (often both fine and coarse) help to distinguish these lesions from capillary–venous malformations. A, Courtesy, Maria Garzon, MD, and Anita Haggstrom, MD; B, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

• Congenital hemangiomas are fully developed at birth, typically presenting as a warm, pink to blue-violet mass or plaque with overlying coarse telangiectasias, surrounded by a vasoconstricted rim and/or radiating veins; unlike true IHs, congenital hemangiomas are GLUT1-negative.

– Rapidly involuting congenital hemangioma (RICH) – rapid involution during the first year of life (Fig. 85.15A,B).

Fig. 85.15 Congenital hemangiomas. A Rapidly involuting congenital hemangioma (RICH) presenting as a violaceous tumor on the upper extremity with surface telangiectasias in a neonate. B Spontaneous involution of the RICH at 5 months of age, with fibrofatty residua. C Non-involuting congenital hemangioma (NICH) in a school-aged child. This lesion was fully formed at birth and is still warm and firm to palpation. Note the coarse telangiectasias and pallor. A, B, Courtesy, Annette Wagner, MD; C, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

– Non-involuting congenital hemangioma (NICH) – postnatal growth in proportion to the child, without involution (Fig. 85.15C).

Kasabach–Merritt Phenomenon (KMP)

• Life-threatening thrombocytopenic coagulopathy associated with a vascular tumor, usually a kaposiform hemangioendothelioma or tufted angioma (see Chapter 94) in an infant (not an IH).

– Prior to onset of KMP, lesions may appear as thin red-violet plaques or deeper masses.

• Presents with a rapidly enlarging, indurated, ecchymotic mass associated with marked thrombocytopenia and a consumptive coagulopathy (Fig. 85.16).

Vascular Malformations

• Categorized based on the predominant type(s) of vascular channels, which are divided into slow- and fast-flow groups:

– Fast-flow: arteriovenous (arterial anomalies + arteriovenous shunting).

Capillary Malformations (CMs) and Related Conditions

Nevus Simplex (Salmon Patch)

• Common congenital capillary stain (not a true CM) on the mid face (forehead, glabella, nasal tip, and philtrum), eyelids, occiput, and nape (‘stork bite’) (Fig. 85.17A,B); multiple lesions may be present and can occur in the lumbar area.

Fig. 85.17 Salmon patches (nevus simplex) versus port-wine stain (PWS) in a V2 distribution. A Involvement of the central face in a symmetrical pattern is common with a salmon patch; such lesions fade over the first few years of life but are sometimes misdiagnosed as a PWS. B Salmon patches in the nape area (‘stork bites’) tend to be more persistent. C In this young infant with a PWS, the skin is smooth. This lesion will persist. B, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD; C, Courtesy, Odile Enjolras, MD.

Port-Wine Stain (PWS)

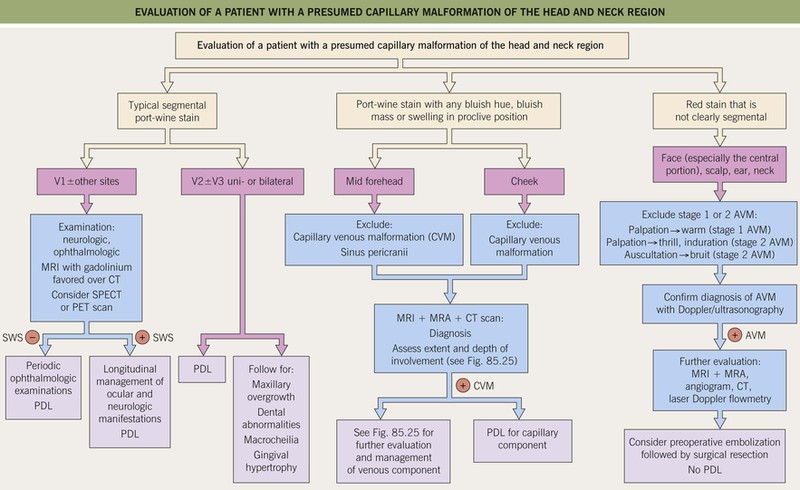

• PWSs present at birth as pinkish-red macules and patches, often in a segmental pattern (Fig. 85.17C).

• Over time, may develop a deeper purplish-red color, and affected skin (especially on the face) often thickens and becomes nodular; overgrowth of underlying soft tissues and bones can also occur (Figs. 85.18 and 85.19).

Fig. 85.18 Facial port-wine stains in a V2 distribution with hypertrophic changes. A Prominent skin thickening and nodularity. B Markedly enlarged gingiva and overgrowth of the right maxilla. Courtesy, Odile Enjolras, MD.

Fig. 85.19 Evaluation of a patient with a presumed capillary malformation of the head and neck region. AVM, arteriovenous malformation; CT, computed tomography; CVM, capillary venous malformation; PDL, pulsed dye laser; MRA, magnetic resonance arteriography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PET, positron emission tomography; SPECT, single photon emission computed tomography; SWS, Sturge–Weber syndrome.

• DDx: in infant: nevus simplex, early or arrested-growth IH; CMTC (especially if on an extremity), stage 1 arteriovenous malformation, verrucous ‘hemangioma’ (congenital red-purple hyperkeratotic plaques, often in a segmental pattern, composed of capillaries and with growth proportional to the child).

• Sturge–Weber syndrome: association of a facial PWS, usually involving the trigeminal V1 dermatome (upper eyelid, forehead) ± other sites (Fig. 85.20), with ipsilateral ocular and leptomeningeal vascular malformations; the latter can lead to glaucoma and neurologic sequelae such as developmental delay and contralateral seizures or hemiparesis.

Fig. 85.20 Infant at risk for Sturge–Weber syndrome. Port-wine stain with involvement of V1 as well as V2 and V3. Courtesy, Odile Enjolras, MD.

• Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis (PPV): forms of ‘twin spotting’ in which a PWS coexists with aberrant Mongolian spots (dermal melanocytosis, also caused by mosaic GNAQ mutations; type 2 PPV) (Fig. 85.21) or a nevus spilus (type 3 PPV); a nevus anemicus may also be present.

Fig. 85.21 Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis type 2. A large port-wine stain and extensive dermal melanocytosis are seen. Courtesy, Odile Enjolras, MD.

• Megalencephaly–capillary malformation (previously macrocephaly–CMTC): reticulated PWS and persistent nevus simplex associated with asymmetric overgrowth, macrocephaly, and developmental delay; due to mosaic PIK3CA mutations (Fig. 85.22).

Cutis Marmorata Telangiectatica Congenita (CMTC)

• Red-purple, broad reticulated vascular pattern intermingled with telangiectasias, ± prominent veins and atrophy; most often affects a limb, which may be hypoplastic; occasionally generalized (Fig. 85.23).

Fig. 85.23 Cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita (CMTC) with atrophy of the affected limb. The color of the broad vascular network can be red-purple (as in this infant) to brownish-purple.

• Adams–Oliver syndrome features CMTC together with aplasia cutis congenita and limb defects (see Table 53.3).

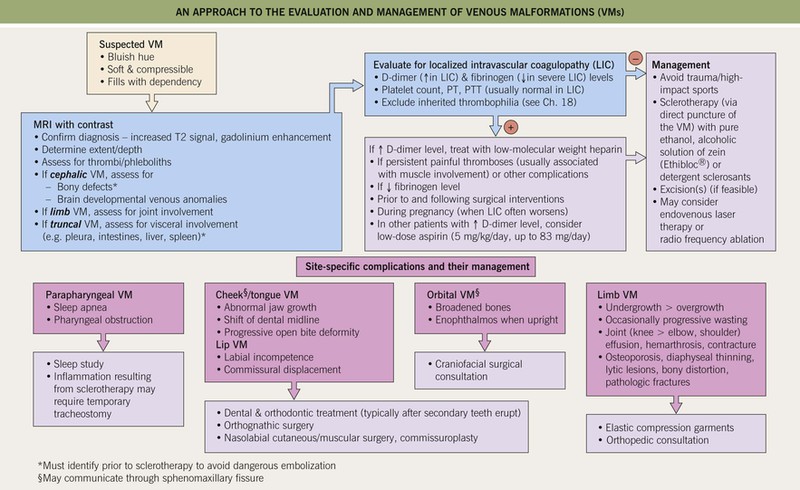

Venous Malformations (VMs; Former Misnomer of ‘Cavernous Hemangioma’)

Classic VMs

• Soft, compressible bluish nodules that fill with dependency; may be focal, segmental, or widespread, and often extend into underlying muscles and bones (Fig. 85.24).

Fig. 85.24 Venous malformations (VMs). A Distortion of the tongue and lower lip has led to an open bite. B The skin and muscles of the entire arm are affected, with soft bluish nodules and obvious swelling in the dependent position. C This VM has a segmental distribution on the right trunk and involvement of the ipsilateral arm. Courtesy, Odile Enjolras, MD.

• Both multiple cutaneous and mucosal VMs with autosomal dominant inheritance and sporadic VMs can result from mutations in the TEK gene, which encodes an endothelial cell-specific tyrosine kinase.

• An approach to the evaluation and management of VMs at different sites is presented in Fig. 85.25.

Glomuvenous Malformations (GVMs; Previously Known As Glomangiomatosis)

• Pink to blue-purple nodules and cobblestoned plaques that resist full compression and are painful upon palpation; may be focal, segmental, or widespread and (unlike classic VMs) are typically limited to the skin and subcutis (Fig. 85.26).

• Autosomal dominant inheritance due to mutations in the glomulin gene (GLMN).

Lymphatic Anomalies

Lymphatic Malformations

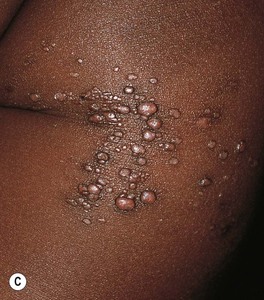

• Microcystic LM (‘lymphangioma circumscriptum’): clusters of clear or hemorrhagic, vesicle-like papules favoring the proximal limbs and chest; intermittent hemorrhage and leakage of lymph can occur (Fig. 85.27A–D).

Fig. 85.27 Lymphatic malformations (LMs). A–D Microcystic LMs presenting as clusters of clear or hemorrhagic vesicles, with active bleeding from lesions in the mouth. The crops of vesicles in (B) recurred years after surgical resection (utilizing grafting and linear closure) of a large microcystic LM affecting the skin and deeper structures of the arm and thorax. E Macrocystic LM on the lateral trunk. The mass was soft except for a focal firm area of hemorrhage associated with bruise-like discoloration of the overlying skin. A, B, Courtesy, Odile Enjolras, MD; D, E, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

• Macrocystic LM (‘cystic hygroma’): ballotable subcutaneous masses representing larger lymphatic cysts; favor the neck, axilla, and lateral chest wall (Fig. 85.27E).

• Radiologic evaluation: ultrasonography, MRI with gadolinium (lack enhancement).

Primary Lymphedema

Arteriovenous Malformations (AVMs)

• Fast-flow malformations with potential for serious complications (e.g. amputation, deformity).

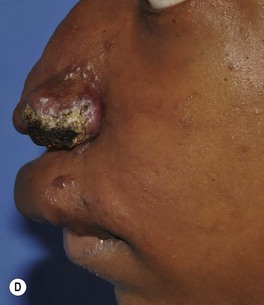

• Divided into four stages based on clinical severity:

– Stage 1 – dormant: red, warm and macular (mimicking a PWS) or slightly infiltrated (Fig. 85.28A,B).

Fig. 85.28 Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs). A, B Dormant (stage 1) AVMs mimicking a port-wine stain (A) and infantile hemangioma (B). C Expanding (stage 2) centrofacial AVM associated with AVMs of the retina and brain in a boy with Bonnet–Dechaume–Blanc syndrome. D Destructive (stage 3) AVM that has led to cutaneous necrosis. Courtesy, Odile Enjolras, MD.

– Stage 2 – expansion: warm mass with thrill/throbbing and dilated draining veins (Fig. 85.28C).

– Stage 3 – destruction: pain, necrosis, and ulceration; ± lytic bone lesions (Fig. 85.28D).

– Stage 4 – cardiac decompensation: high-output cardiac failure.

• Radiologic evaluation: ultrasonography, MRI/MRA, arteriography.

• Rx: complete excision after judicious preoperative embolization.

• Acroangiodermatitis (pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma; see Chapter 86) can occur in association with a lower extremity AVM.

– Bonnet–Dechaume–Blanc (Wyburn–Mason) syndrome: cutaneous facial + orbit/eye and/or brain (see Fig. 85.28C).

Syndromes Associated with Complex–Combined or Multiple Types of Vascular Malformations

• Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome: CM + VM ± LM associated with progressive overgrowth of the affected extremity; well-demarcated geographic stains usually have a lymphatic component, which increases the likelihood of massive overgrowth and cellulitis; risk of deep venous thrombosis/pulmonary embolism (Fig. 85.29).

Fig. 85.29 Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome (KTS). Dilated incompetent veins and an enlarged lower limb are evident. The sharply demarcated geographic borders of this capillary stain and the superimposed purple papulovesicles (representing lymphangiectasias) are clues to the presence of a lymphatic malformation. In contrast, KTS without a lymphatic component often presents with an ill-defined patchy capillary stain in a segmental or haphazard distribution.

• Proteus syndrome (see Table 51.3): mosaic disorder due to AKT1 mutations; can feature CM, VM, and/or LM.

• PTEN hamartoma–tumor syndrome (see Chapter 52): often intramuscular fast-flow anomalies associated with ectopic fat and dilated draining veins; ± CM and LM components.

For further information see Chs. 103 and 104. From Dermatology, Third Edition.