Chapter 16 Inappropriate Sinus Tachycardia

Pathophysiology

Sinus tachycardia is a physiological response to sympathetic activation and/or parasympathetic withdrawal, such as during exercise, anxiety, pain, hypovolemia, orthostatic hypotension, fever, infections, hyperthyroidism, hypoglycemia, anemia, myocardial infarction, heart failure, pericarditis, diabetes-related autonomic dysfunction, drug abuse, catecholamine infusions, anticholinergic drugs, tobacco, caffeine, alcohol, and beta-blocking agent withdrawal. Inappropriate sinus tachycardia (IST) is a nonparoxysmal tachyarrhythmia characterized by a persistent increase in resting sinus rate unrelated to, or out of proportion with, the level of physical, emotional, pathological, or pharmacological stress or an exaggerated heart rate response to minimal exertion or a change in body posture.1 IST is neither a response to a pathological process (e.g., heart failure, hyperthyroidism, or drug effects) nor a result of physical deconditioning.

The underlying mechanism of IST remains poorly understood. Several potential mechanisms have been suggested, including enhanced automaticity of the sinus node, altered sinus nodal intrinsic regulation, disorder of autonomic responsiveness of the sinus node, and sympathovagal imbalance, with excessive sympathetic drive or reduced vagal influence on the sinus node, or both. A primary abnormality of sinus node function has been suggested, as evidenced by a higher intrinsic heart rate (after muscarinic and beta-receptor blockade) than that found in normal controls or a blunted response to adenosine with less sinus cycle length prolongation than in control subjects (with and without autonomic blockade).2,3 In addition, beta-adrenergic receptor hypersensitivity, alpha-adrenergic receptor hyposensitivity, M2 muscarinic receptor abnormalities, brain stem dysregulation, depressed efferent cardiovagal reflex, and impaired baroreflex control are likely explanations. Chronic beta-receptor stimulation by autoantibodies and autonomic neuritis or autonomic neuropathy can play a role in some cases. The extent to which each of these mechanisms contributes to tachycardia and associated symptoms is unknown, but the underlying mechanisms are likely multifactorial and complex.4–7

In some patients, there can be an overlap between IST and disorders such as chronic fatigue syndrome and neurocardiogenic syncope, and other patients can have a psychological component of hypersensitivity to somatic input.8 Other groups with similar or overlapping laboratory findings and clinical course include patients with hyperadrenergic syndrome, idiopathic hypovolemia,9 orthostatic hypotension, and mitral valve prolapse syndrome.2,3

Clinical Considerations

Epidemiology

Almost all patients afflicted with IST are young women (mean age, 38 ± 12 years), and many of them are hypertensive. IST affects people working in health care in disproportionate numbers. The explanation for these findings is lacking.3,10 The prevalence of IST in a middle-aged population (up to 1.16% in one report) appears to be higher than previously assumed. Despite the chronic nature of the disorder and long-lasting symptoms, the natural course and prognosis of IST are benign.10

Clinical Presentation

The most prominent symptoms are palpitations, fatigue, and exercise intolerance. IST can also be associated with a host of other symptoms, including chest pain, dyspnea, lightheadedness, dizziness, presyncope, and syncope. The clinical presentation of the arrhythmia is highly variable, ranging from totally asymptomatic patients identified during routine medical examination to those with paroxysmal short episodes of palpitations to individuals with chronic, incessant, and incapacitating symptoms.2,10 The risk of tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy in untreated patients is unknown but is likely to be low.1,10,11

Initial Evaluation

IST is an ill-defined clinical syndrome with diverse clinical manifestations. There is no gold standard to make a definitive diagnosis of IST, and the diagnosis remains a clinical one after exclusion of other causes of symptomatic tachycardia. Clinical examination and routine investigations allow elimination of secondary causes for the tachycardia but are generally not helpful in establishing the diagnosis of IST.1–3

The syndrome of IST is characterized by the following: (1) a relative or absolute increase in sinus rate out of proportion to the physiological demand (there can be an increased resting sinus rate of more than 100 beats/min or an exaggerated heart rate response to minimal exertion or change in body posture); (2) P wave axis and morphology during tachycardia that are similar or identical to those noted during normal sinus rhythm; (3) lack of secondary causes of sinus tachycardia; and (4) markedly distressing symptoms of palpitations, fatigue, dyspnea, and anxiety during tachycardia, with an absence of symptoms during normal sinus rates.1–412

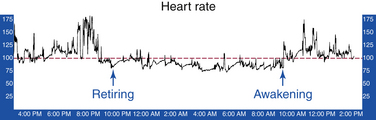

Ambulatory Holter recordings characteristically demonstrate a mean heart rate of more than 90 to 95 beats/min (Fig. 16-1). However, some patients have either a physiological or normal heart rate at rest (less than 85 beats/min) with an inappropriate tachycardia response to a minimal physiological challenge or a moderately elevated resting heart rate (more than 85 beats/min) with an accentuated (inappropriate) heart rate response to minimal exertion.2,3,13 However, this quantitative definition of inappropriate is arbitrary, and validation of the reproducibility of the heart rate and activity correlation can be challenging.12,14

Exercise ECG testing typically shows an early and excessive increase of heart rate in response to minimal exercise (heart rate greater than 130 beats/min within 90 seconds of exercise; Bruce protocol). This heart rate response is differentiated from physical deconditioning by chronicity and the presence of associated symptoms.2

Isoproterenol provocation helps demonstrate sinus node hypersensitivity to beta-adrenergic stimulation. Isoproterenol is administered as escalating intravenous boluses at 1-minute intervals, starting at 0.25 µg, with doubling of the dose every minute, until a target heart rate increase of 35 beats/min higher than baseline or a maximum heart rate of 150 beats/min is reached. In patients with IST, the target heart rate is reached with an isoproterenol dose of 0.29 ± 0.1 µg (versus 1.27 ± 0.4 µg in normal controls).2

Invasive electrophysiological (EP) testing may be considered when other arrhythmias are suspected or when a decision to proceed with catheter ablation is undertaken. It is important to recognize that sinus node modification to target IST is a clinical decision, and it must be made prior to the invasive EP study itself. The diagnosis of IST and the treatment approach have to be established before the patient is brought to the EP laboratory.2,3

IST shares several characteristics with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), and it is sometimes challenging to differentiate between the two conditions. POTS is characterized by the presence of symptoms of orthostatic intolerance (i.e., the provocation of symptoms on standing that are relieved by recumbence) associated with a heart rate increase of 30 beats/min (or a rate that exceeds 120 beats/min) that occurs within the first 10 minutes of standing or upright tilt and is not associated with other chronic debilitating conditions such as prolonged bed rest or the use of medications known to diminish vascular or autonomic tone. Patients with POTS tend to display a more pronounced degree of postural change in heart rate than do those with IST. Additionally, in the supine position, the heart rate in patients with POTS rarely exceeds 100 beats/min, whereas in IST the resting heart rate is often higher than 100 beats/min. Patients with IST do not display the same degree of postural change in norepinephrine levels as do patients with hyperadrenergic POTS. The distinction between IST and POTS is important because catheter ablation of the sinus node rarely improves, and can even worsen, symptoms in patients with POTS.15

Principles of Management

The treatment of IST is predominantly symptom driven. Medical management remains the mainstay of therapy. Beta-blockers can be useful and should be prescribed as first-line therapy for most patients. Nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (verapamil and diltiazem) can also be effective.1 However, pharmacological therapy for IST has been limited by the poor long-term tolerance to the drugs and the disappointing long-term outcome.

Ivabradine is a novel selective inhibitor of cardiac pacemaker If ion current, which is highly expressed in the sinus node and contributes to sinus node automaticity. Ivabradine selectivity induces heart rate reduction in humans and animals without any modification in cardiac contractility and atrioventricular and intraventricular conduction times. Blockade of the If current induced by ivabradine is dose and heart rate dependent, resulting in greater effects during fast heart rates and limiting the risk of symptomatic bradycardia. This agent is commonly used to relieve pain in patients affected by chronic stable angina. Preliminary data suggest that orally administered ivabradine lowers the mean daily and maximal heart rates in patients with IST, improves symptoms, enhances exercise-stress tolerance, and markedly improves quality of life, even in patients refractory to beta-blocking therapy. This pharmacological treatment could be considered a second-line therapy in patients refractory to and intolerant of beta-blockers and nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers. However, more large-cohort studies are needed to confirm these preliminary results.11,16,17

Despite advances in ablation technologies, the long-term success of catheter ablation for IST remains disappointing. Nevertheless, sinus node modification by catheter ablation remains a potentially important therapeutic option in the most refractory cases of IST.1,2

Electrophysiological Testing

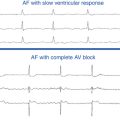

The goals of EP testing in patients with IST are to exclude other tachycardias that can mimic sinus tachycardia, such as atrial tachycardia (AT) originating near the superior aspect of the crista terminalis or right superior pulmonary vein, and to ensure that the tachycardia occurring spontaneously or, more likely with isoproterenol infusion, acts in a manner consistent with an exaggeration of normal sinus node physiology.2,3

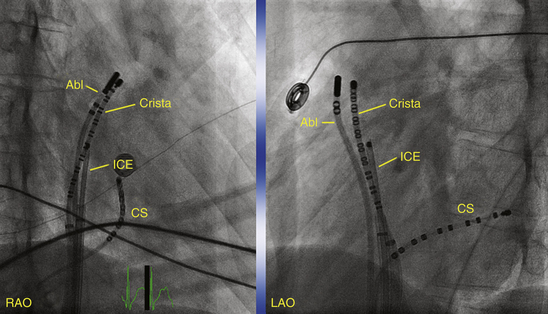

For activation sequence mapping, a multipolar (20-pole) crista catheter is placed along the crista terminalis in addition to the catheters used for a routine EP evaluation (coronary sinus, His bundle, and right ventricular apex). The crista catheter is positioned on the crista terminalis from the superomedial aspect originating at the junction of the superior vena cava (SVC) and right atrial (RA) appendage, with continuation along the crista toward the junction of the inferior vena cava and RA inferolaterally. Catheter contact with the crista terminalis can be enhanced by using a long sheath (Fig. 16-2). Intracardiac echocardiography (ICE) may also be used to identify the crista terminalis and guide mapping catheter positioning as well as radiofrequency (RF) ablation (see later).2,3

Exclusion of Other Arrhythmia Mechanisms

Both sinus node reentrant tachycardia and focal AT have to be excluded. Sinus node reentry is easily and reproducibly initiated with atrial extrastimulation, and AT can be initiated with atrial extrastimulation, burst pacing, or adrenergic stimulation, whereas IST cannot be initiated with programmed electrical stimulation. Furthermore, AT and the sinus node reentrant tachycardia rate can shift suddenly at initiation, although AT can then warm up over a few beats, as opposed to the gradual increase of the IST rate over seconds to minutes.

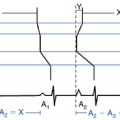

Sinus node reentry is easily and reproducibly terminated with programmed stimulation, whereas IST cannot be terminated with programmed stimulation. Termination of focal AT and sinus node reentry is sudden, as opposed to gradual slowing (cooldown) of the IST rate (Fig. 16-3). Vagal maneuvers result in abrupt termination of sinus node reentry and in either no effect or abrupt termination of AT, as opposed to gradual slowing and inferior shift down the crista terminalis of the site of origin of IST. Abrupt termination of the tachycardia with a single RF application suggests AT, because IST originates from a widespread area involving the superior crista terminalis.

Ablation

Target of Ablation

Understanding the anatomy and physiology of the sinus node (see Chap. 8) is critical for identifying the target of ablation for sinus node modification. The sinus node region is a distributed complex characterized by rate-dependent site differentiation (i.e., there is anatomical distribution of impulse generation with changes in sinus rate), which allows for targeted ablation to eliminate the fastest sinus rates while maintaining some degree of sinus node function.18

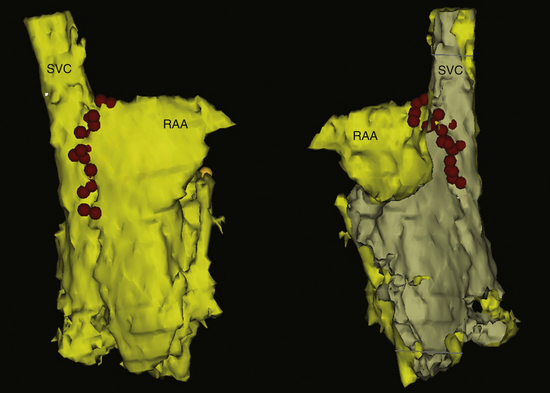

Sinus node modification targets the site of most rapid discharge, generally at the superior aspect of the crista terminalis. One must recognize, however, that sinus node modification is not a focal ablation, but requires complete abolition of the cranial portion of the sinus node complex (Fig. 16-4). Ideally, this procedure eliminates the areas of the sinus node responsible for rapid rates while preserving some chronotropic competence.

Ablation Technique

The crista terminalis is not visible on fluoroscopy and has a varied course among patients. Therefore, some operators prefer using ICE to help identify the crista, position the tip of the ablation catheter with firm contact on the crista, and assess the RF lesion (see Fig. 11-23).19,20

A three-dimensional mapping system (CARTO, NavX) can also help delineate relevant anatomical structures (SVC, boundaries of atrium), define the extent of the earliest site of activation during IST, delineate the course of the phrenic nerve (sites at which pacing stimulates the diaphragm), and catalog sites of ablation.21,22

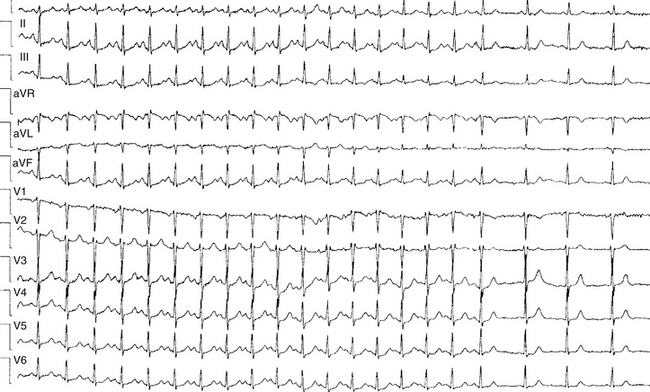

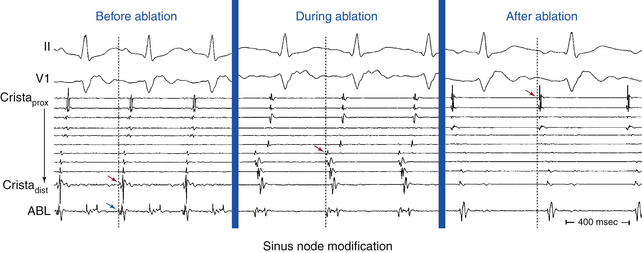

A multipolar catheter is placed along the crista terminalis (with or without ICE guidance; see Fig. 16-2). A standard ablation catheter with a 4- or 8-mm-tip or an irrigated-tip catheter is used for RF application. RF power is adjusted to achieve a tip temperature of 50° to 60°C or an impedance drop of 5 to 10 Ω, or both. RF lesions are applied as guided by the earliest atrial activation time, usually along superior regions of the crista terminalis using the guidance of the crista catheter. The local endocardial activation time recorded by the ablation catheter at successful sites typically precedes the onset of the surface P wave during the tachycardia by 25 to 45 milliseconds (Fig. 16-5).

RF ablation is performed under maximal adrenergic stimulation with isoproterenol (with or without parasympathetic blockade with atropine) to reveal the superior portions of the crista terminalis as the earliest sites of atrial activation. The medial portion of the crista as it courses in front of the SVC is usually the site of earliest activation for the fastest sinus rates; this portion of the crista should be targeted by RF ablation first. Progressively inferior portions of the crista are then ablated until target heart rate reduction is achieved. This technique often requires ablating an estimated area of 12 ± 4 × 19 ± 5 mm.21

RF energy delivery at any one site should probably be limited to 30 seconds because these are usually closely spaced applications, which carry the risk of char formation with longer applications. Pacing from the ablation catheter tip at high output (5 to 10 mA) before each RF application to verify the absence of diaphragmatic stimulation is necessary to avoid phrenic nerve injury. Rarely, pericardial access with epicardial ablation has been necessary. Then, avoidance of the phrenic nerve can be even more problematic and require instilling saline into the pericardial space or placing a balloon catheter through a second pericardial access to separate the phrenic nerve physically from the ablation zone.2,3,20,22

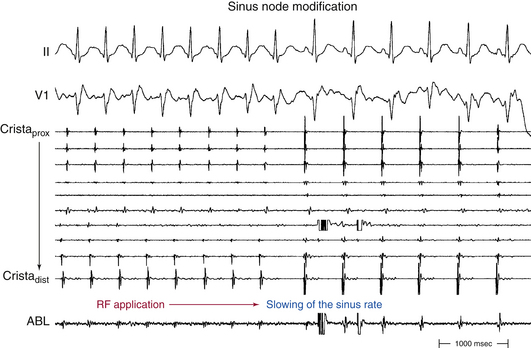

Acceleration of the sinus rate followed by a marked subsequent rate reduction or the appearance of a junctional rhythm during ablation is an indicator of successful ablation sites, and thereafter delivery of RF energy should be continued for at least 60 to 90 seconds. Most patients demonstrate a stepwise reduction in sinus rate during the course of ablation, associated with migration of the site of earliest atrial activation in a craniocaudal direction along the crista terminalis (see Fig. 16-5). However, it is not uncommon to observe an abrupt reduction in the sinus rate in response to RF ablation at a focal site of earliest atrial activation (Fig. 16-6).22 Echocardiographic lesion characteristics using ICE can also provide a guide for directing additional RF lesions. The effective RF lesion has an increased or changed echodensity completely extending to the epicardium with the development of a trivial linear low-echodensity or echo-free interstitial space, which suggests a transmural RF lesion.23

Endpoints of Ablation

Acute procedural success is defined as the following: (1) abrupt reduction of the sinus rate by 30 beats/min or more during RF delivery or a 30% decline in maximum heart rate during infused isoproterenol and atropine; (2) persistence of a reduced sinus rate; (3) maintenance of a superiorly directed P wave (negative P wave in lead III); and (4) inferior shift of the site of earliest atrial activation down the crista terminalis, even with maximal adrenergic stimulation.2,3,22

RF ablation of IST often is difficult and requires multiple RF applications; a mean of 12 RF applications (range, 6 to 92) was required in one study (see Fig. 16-4).19 The resilience of the sinus node to endocardial catheter ablation can be explained, in part, by the architectural features of the node—the dense matrix of connective tissue in which the specialized sinus node cells are packed; the cooling effect of the nodal artery; the subepicardial nodal location; and the thick terminal crest, particularly in relation to the nodal portion caudal to the sinus node artery. Additionally, the length of the sinus node, the absence of an insulating sheath, the presence of nodal radiations, and caudal fragments offer a potential for multiple breakthroughs of the nodal wavefront.18

Outcome

Prior to undertaking ablation of the sinus node for IST, the physician and patient should have realistic expectations and understanding of the goals of ablation and potential outcomes. Relatively few patients will achieve the desired combination of relief of symptoms and normal resting heart rate and chronotropic response without the need for implantation of a permanent pacemaker. In some patients, symptoms persist despite an acceptable technical result.2,3

RF ablation is at best only a modestly effective technique for managing patients with IST. The long-term success rate is variable, ranging between 23% and 83%.8 Complete ablation of the sinus node resulting in junctional rhythm has better long-term success (72%) but requires pacemaker insertion. Most recurrences occur 1 to 6 months after the procedure and are typically related to tachycardia recurrence after an initially successful procedure. A repeat procedure may be necessary in patients with intolerable symptoms. Symptomatic recurrence or persistence of symptoms in the absence of documented IST and despite persisting evidence of a successful EP outcome has been observed in some cases. Persistent symptoms despite heart rate reduction may be suggestive of a more global dysautonomia that also happens to affect the sinus node.2,3,20–22

Complications of sinus node modification include cardiac tamponade, SVC syndrome, diaphragmatic paralysis, and sinus node dysfunction.24 Cardiac tamponade is rare and is usually caused by penetration of an unattended right ventricular catheter in a thin female patient with rapid and vigorous heart action because of high-dose isoproterenol infusion. Transient SVC syndrome can develop because of extensive lesion creation and edema at the SVC-RA junction. This can rarely cause permanent SVC stenosis. More targeted ablation using ICE may help avoid this complication. Diaphragmatic paralysis secondary to damage to the right phrenic nerve should be minimized if ablative lesions are confined to the crista itself or placed just anterior to it. Using ICE to guide ablation makes this complication unlikely because the phrenic nerve is a posterior structure. Pacing with a high output of 10 mA from the ablation catheter at the target site without capture of the phrenic nerve and continuous pacing in the SVC to capture the phrenic nerve during RA ablation are reassuring, but their efficacy has never been assessed. Additionally, suspicion of phrenic nerve injury should be considered in the case of hiccup, cough, or decrease in diaphragmatic excursion during energy delivery. Early recognition of phrenic nerve injury during RF delivery allows the immediate interruption of the application prior to the onset of permanent injury and is associated with rapid recovery of phrenic nerve function. Persistent junctional rhythm requiring pacemaker insertion is rare. Such junctional rhythm usually disappears with the return of sinus rhythm within several days.2,3,22

1. Blomstrom-Lundqvist C., Scheinman M.M., Aliot E.M., et al. ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular arrhythmias—executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Supraventricular Arrhythmias). Circulation. 2003;108:1871-1909.

2. Line D., Callans D. Sinus rhythm abnormalities. In: Zipes D.P., Jalife J., editors. Cardiac electrophysiology: from cell to bedside. ed 4. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004:479-484.

3. Desh M., Karch M., Kalman J., et al. Ablation of inappropriate sinus tachycardia. In: Huang S., Wilber D., editors. Radiofrequency catheter ablation of cardiac arrhythmias: basic concepts and clinical applications. ed 2. Armonk, NY: Futura; 2000:165-174.

4. Leon H., Guzman J.C., Kuusela T., et al. Impaired baroreflex gain in patients with inappropriate sinus tachycardia. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2005;16:64-68.

5. Nattel S. Inappropriate sinus tachycardia and beta-receptor autoantibodies: a mechanistic breakthrough? Heart Rhythm. 2006;3:1187-1188.

6. Chiale P.A., Garro H.A., Schmidberg J., et al. Inappropriate sinus tachycardia may be related to an immunologic disorder involving cardiac beta adrenergic receptors. Heart Rhythm. 2006;3:1182-1186.

7. Zhou J., Scherlag B.J., Niu G., et al. Anatomy and physiology of the right interganglionic nerve: implications for the pathophysiology of inappropriate sinus tachycardia. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008;19:971-976.

8. Shen W.K., Low P.A., Jahangir A., et al. Is sinus node modification appropriate for inappropriate sinus tachycardia with features of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome? Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2001;24:217-230.

9. Goldstein D.S., Holmes C., Frank S.M., et al. Cardiac sympathetic dysautonomia in chronic orthostatic intolerance syndromes. Circulation. 2002;106:2358-2365.

10. Still A.M., Raatikainen P., Ylitalo A., et al. Prevalence, characteristics and natural course of inappropriate sinus tachycardia. Europace. 2005;7:104-112.

11. Winum P.F., Cayla G., Rubini M., et al. A case of cardiomyopathy induced by inappropriate sinus tachycardia and cured by ivabradine. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2009;32:942-944.

12. Shen W.K. Modification and ablation for inappropriate sinus tachycardia: current status. Card Electrophysiol Rev. 2002;6:349-355.

13. Brady P.A., Low P.A., Shen W.K. Inappropriate sinus tachycardia, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, and overlapping syndromes. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2005;28:1112-1121.

14. Vatasescu R., Shalganov T., Kardos A., et al. Right diaphragmatic paralysis following endocardial cryothermal ablation of inappropriate sinus tachycardia. Europace. 2006;8:904-906.

15. Grubb B.P. Postural tachycardia syndrome. Circulation. 2008;117:2814-2817.

16. Schulze V., Steiner S., Hennersdorf M., Strauer B.E. Ivabradine as an alternative therapeutic trial in the therapy of inappropriate sinus tachycardia: a case report. Cardiology. 2008;110:206-208.

17. Calo L., Rebecchi M., Sette A., et al. Efficacy of ivabradine administration in patients affected by inappropriate sinus tachycardia. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:1318-1323.

18. Sanchez-Quintana D., Cabrera J.A., Farre J., et al. Sinus node revisited in the era of electroanatomical mapping and catheter ablation. Heart. 2005;91:189-194.

19. Ren J.F., Marchlinski F.E., Callans D.J., Zado E.S. Echocardiographic lesion characteristics associated with successful ablation of inappropriate sinus tachycardia. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2001;12:814-818.

20. Mantovan R., Thiene G., Calzolari V., Basso C. Sinus node ablation for inappropriate sinus tachycardia. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2005;16:804-806.

21. Marrouche N.F., Beheiry S., Tomassoni G., et al. Three-dimensional nonfluoroscopic mapping and ablation of inappropriate sinus tachycardia: procedural strategies and long-term outcome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:1046-1054.

22. Man K.C., Knight B., Tse H.F., et al. Radiofrequency catheter ablation of inappropriate sinus tachycardia guided by activation mapping. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:451-457.

23. Ren J.F., Callans D. Intracardiac echocardiography imaging in radiofrequency catheter ablation for inappropriate sinus tachycardia and atrial tachycardias. In: Ren J.F., Marchlinski F.E., Callans D., editors. Practical intracardiac echocardiography in electrophysiology. Malden, Mass: Blackwell Futura; 2006:74-87.

24. Leonelli F.M., Pisano E., Requarth J.A., et al. Frequency of superior vena cava syndrome following radiofrequency modification of the sinus node and its management. Am J Cardiol. 2000;85:771-774. A9