Chapter 325 Ileus, Adhesions, Intussusception, and Closed-Loop Obstructions

325.3 Intussusception

Diagnosis

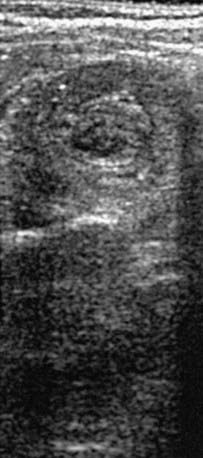

When the clinical history and physical findings suggest intussusception, an ultrasound is typically performed. A plain abdominal radiograph might show a density in the area of the intussusception. Screening ultrasounds for suspected intussusception increases the yield of diagnostic or therapeutic enemas and reduces unnecessary radiation exposure in children with negative ultrasound examinations. The diagnostic findings of intussusception on ultrasound include a tubular mass in longitudinal views and a doughnut or target appearance in transverse images (Fig. 325-1). Ultrasound has a sensitivity of approximately 98-100% and a sensitivity of about 88% in diagnosing intussusception. Air, hydrostatic (saline), and, less often, water-soluble contrast enemas have replaced barium examinations. Contrast enemas demonstrate a filling defect or cupping in the head of the contrast media where its advance is obstructed by the intussusceptum (Fig. 325-2). A central linear column of contrast media may be visible in the compressed lumen of the intussusceptum, and a thin rim of contrast may be seen trapped around the invaginating intestine in the folds of mucosa within the intussuscipiens (coiled-spring sign), especially after evacuation. Retrogression of the intussusceptum under pressure and visualized on x-ray or ultrasound documents successful reduction. Air reduction is associated with fewer complications and lower radiation exposure than traditional contrast hydrostatic techniques.

Bajaj L, Roback MG. Postreduction management of intussusception in a children’s hospital emergency department. Pediatrics. 2003;112:1302-1307.

Bines JE, Kohl KS, Forster J, et al. Acute intussusception in infants and children as an adverse event following immunizations: case definition and guidelines of data collection, analysis, and presentation. Vaccine. 2004;22:569-574.

Bines JE, Liem NT, Justice FA, et al. Risk factors for intussusception in infants in Vietnam and Australia: adenovirus implicated, but not rotavirus. J Pediatr. 2006;149:452-460.

Bonnard A, Demarche M, Dimitriu C, et al. Indications for laparoscopy in the management of intussusception. A multicenter retrospective study conducted by the French study group for pediatric laparoscopy (GECI). J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:1249-1253.

Buettcher M, Baer G, Bonhoeffer J, et al. Three-year surveillance of intussusception in children in Switzerland. Pediatrics. 2007;120:473-480.

Burke MS, Ragi JM, Karamanoukian HL, et al. New strategies in nonoperative management of meconium ileus. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:760-764.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Postmarketing monitoring of intussusception after Rota Teg vaccination—United States, February 1, 2006-February 15, 2007. MMWR. 2007;56:218-222.

Crystal P, Hertzanu Y, Farber B, et al. Sonographically guided hydrostatic reduction of intussusception in children. J Clin Ultrasound. 2002;30:343-348.

Fischer TK, Bihrmann K, Perch M, et al. Intussusception in early childhood: a cohort study of 1.7 million children. Pediatrics. 2004;114:782-785.

Greenberg D, Givon-Lavi N, Newman N, et al. Intussusception in children in southern Israel: disparity between 2 populations. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:236-240.

Henrikson S, Blane CE, Koujok K, et al. The effect of screening sonography on the positive rate of enemas for intussusception. Pediatr Radiol. 2003;33:190-193.

Henry MCW, Brever CK, Tashjian DB, et al. The appendix sign: a radiographic marker for irreducible intussusception. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:487-489.

Koumanidou C, Vakaki M, Pitsoulakis G, et al. Sonographic detection of lymph nodes in the intussusception of infants and young children: clinical evaluation and hydrostatic reduction. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;178:445-450.

Kubota A, Imura K, Yagi M, et al. Functional ileus in neonates: Hirschsprung’s disease–allied disorders versus meconium-related ileus. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1999;9:392-395.

O’Ryan M, Lucero Y, Pena A, et al. Two year review of intestinal intussusception in six large public hospitals of Santiago, Chile. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22:717-721.

Shteyer E, Koplewitz BZ, Gross E, et al. Medical treatment of recurrent intussusception associated with intestinal lymphoid hyperplasia. Pediatrics. 2003;111:682-685.

Sorantin E, Lindbichler F. Management of intussusception. Eur Radiol. 2004;14:146-154.

Williams H. Imaging and intussusception. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2008;93:30-36.