46

Ichthyoses and Erythrokeratodermas

• Clinical features that are useful in determining the type of ichthyosis include the time of presentation (e.g. at birth, ± a collodion membrane, vs. later in life), the quality and distribution of the scaling, other cutaneous manifestations (e.g. erythroderma, blistering, abnormal hair), and extracutaneous or laboratory findings (Table 46.1).

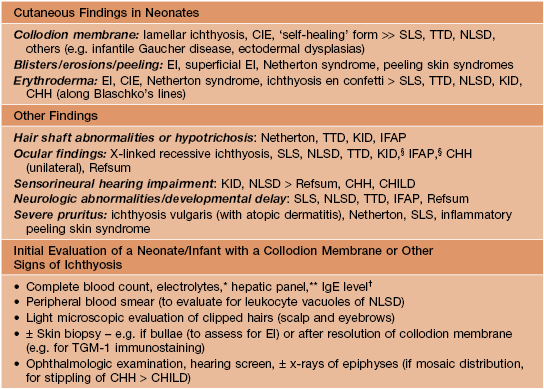

Table 46.1

Clues to the diagnosis of ichthyoses and erythrokeratodermas.

The disorders in this table are discussed in greater detail in the text or Table 46.2. Other rare ichthyoses and related disorders can also present with these findings.

§ Keratitis has variable onset.

* Hypernatremic dehydration occurs primarily in collodion babies and neonates with Netherton syndrome, EI, or Harlequin ichthyosis.

** Elevated transaminases are common in NLSD.

† Increased in Netherton and inflammatory peeling skin syndromes.

CIE, congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma; CHH, Conradi–Hünermann–Happle syndrome; EI, epidermolytic ichthyosis; CHILD, congenital hemidysplasia with ichthyosiform nevus and limb defects; IFAP, ichthyosis follicularis with atrichia and photophobia; KID, keratitis–ichthyosis–deafness syndrome; NLSD, neutral lipid storage disease; SLS, Sjögren–Larsson syndrome; TGM-1, transglutaminase-1; TTD, trichothiodystrophy.

• A few ichthyoses have characteristic histologic features (e.g. epidermolytic ichthyosis; see below).

Ichthyosis Vulgaris (IV)

• The most common disorder of cornification, with a prevalence of at least 1 in 200.

• Mild to moderate scaling favors the extensor extremities (Fig. 46.1), ranging from fine white scales to larger adherent scales (especially on the lower legs); the trunk, scalp, and forehead are occasionally affected, and flexural sites are characteristically spared.

Fig. 46.1 Ichthyosis vulgaris. Fine white scales on the lower extremities. Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

• Associated findings include hyperlinear palms (Fig. 46.2), keratosis pilaris, and atopic dermatitis (25–50% of patients, ± other atopic disorders such as asthma and allergic rhinitis).

Fig. 46.2 Hyperlinear palms in ichthyosis vulgaris. Courtesy, S. J. Bale, PhD, and J. J. DiGiovanna, MD.

X-Linked Recessive Ichthyosis (XLRI; Steroid Sulfatase Deficiency)

• The underlying steroid sulfatase deficiency is caused by deletion of the entire STS gene on chromosome Xp22 in ~90% of patients; XLRI is occasionally part of a contiguous Xp microdeletion syndrome that also includes Kallman syndrome (hypogonadotropic hypogonadism with anosmia) and X-linked recessive chondrodysplasia punctata.

• Affected neonates may have generalized exfoliation of translucent scales, followed during infancy by the development of characteristic dark brown, polygonal, adherent scales favoring the neck, preauricular area, scalp (especially in young children), extremities, and trunk; the palms, soles, and flexural sites tend to be spared (Fig. 46.3).

Fig. 46.3 X-linked recessive ichthyosis. Large light brown (A) and more prominent dark brown (B) scales on the lower leg. C Smaller dark brown scales on the trunk, with sparing of the skin folds. D Dark scales on the neck, sometimes referred to as a ‘dirty neck.’ A–C, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD; D, Courtesy, Gabriele Richard, MD, and Franziska Ringpfeil, MD.

Epidermolytic Ichthyosis (EI; Bullous Congenital Ichthyosiform Erythroderma, Epidermolytic Hyperkeratosis [EHK])

• Presents at birth with erythroderma, peeling skin, and erosions (Fig. 46.4A); sepsis, dehydration, and electrolyte imbalances may occur.

Fig. 46.4 Epidermolytic ichthyosis (bullous congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma). A Erythroderma with widespread peeling and erosions during the neonatal period. B Later development of hyperkeratosis with focal erosions. C Hyperkeratosis with a cobblestone pattern on the dorsal hand. D Corrugated hyperkeratosis in the antecubital fossa. A, B, Courtesy, Eugene Mirrer, MD; C, Courtesy, S. J. Bale, PhD, and J. J. DiGiovanna, MD; D, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

• Skin fragility decreases over time, with development of widespread hyperkeratosis that forms corrugated ridges in flexures and a cobblestone pattern on extensor surfaces of joints (Fig. 46.4B–D); palmoplantar keratoderma (PPK) is seen in patients with KRT1 mutations.

• DDx: in neonates – epidermolysis bullosa, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, other erosive disorders (see Chapter 28); in children/adults – superficial EI, ichthyosis hystrix of Curth–Macklin, other ichthyoses with nonscaling hyperkeratosis (e.g. Sjögren–Larsson and KID syndromes).

• Rx in neonates: protective isolation, emollients, and monitoring.

• Superficial epidermolytic ichthyosis (ichthyosis bullosa of Siemens) is a related autosomal dominant condition due to mutations in the keratin 2 gene (KRT2), which is expressed only in the upper epidermis; affected individuals have milder, more superficial skin shedding (‘molting’; Fig. 46.5), minimal erythema, and no PPK.

Nonsyndromic Autosomal Recessive Congenital Ichthyosis (ARCI): Lamellar Ichthyosis and Congenital Ichthyosiform Erythroderma (CIE)

• Lamellar ichthyosis and CIE exist on a phenotypic spectrum, and nonsyndromic ARCI with these clinical findings can be caused by mutations in at least seven different genes, including those encoding transglutaminase 1 (TGM1; most common), two lipoxygenases (ALOX12B, ALOXE3), and an ABC lipid transporter (ABCA12).

Collodion Baby

• Infants with ARCI (and occasionally other ichthyoses; see Table 46.1) are often born covered by a taut, shiny, transparent membrane resembling plastic wrap, which leads to ectropion, eclabium, and distortion of the nose and ears (Fig. 46.6).

Fig. 46.6 Collodion baby. A Day 1 with ectropion and eclabium. B Day 8 with erythema and diffuse mild scaling and misshapen ears.

• Within 2 weeks, the membrane peels off in sheets and a transition to the underlying disease phenotype takes place; a subset of collodion babies with underlying mutations in TGM1, ALOX12B, or ALOXE3 have a ‘self-healing’ phenotype where the skin is fairly normal in appearance when the membrane resolves.

Lamellar Ichthyosis

• Characterized by large, brown, plate-like scales with little or no associated erythema (Fig. 46.7).

Fig. 46.7 Lamellar ichthyosis. A Large, plate-like scales on the lower extremities forming a mosaic pattern. B Obvious ectropion as well as plate-like scales. A, Courtesy, Gabriele Richard, MD, and Franziska Ringpfeil, MD.

• Rx: oral retinoids (e.g. acitretin) for severe disease; use of topical retinoids (e.g. tazarotene) and keratolytics is limited by irritation and (for the latter agents) potential systemic absorption if applied to an extensive area; longitudinal ophthalmologic care can help to prevent complications of ectropion.

Congenital Ichthyosiform Erythroderma

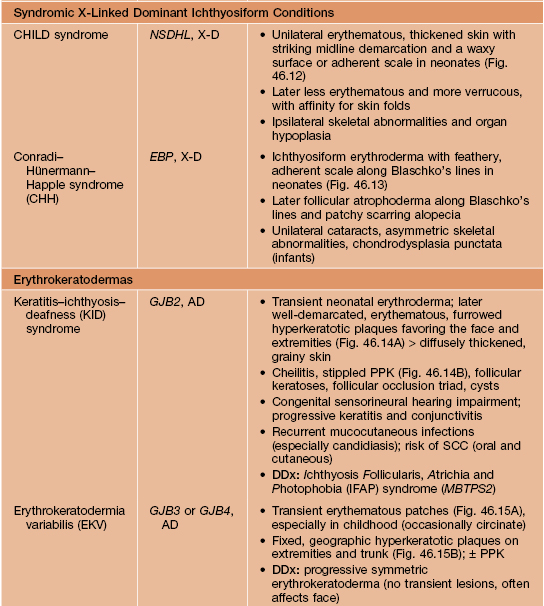

• Characterized by erythroderma and small white scales, often with a powdery consistency, in a generalized distribution (Fig. 46.8).

Fig. 46.8 Congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma. The differential diagnosis may include other causes of erythroderma (see Chapter 8). A Intense redness and fine, flaky, white scale on the trunk and arms. Close-up of fine white (B) and coarser yellowish (C) scale in a background of prominent erythema. A, B, Courtesy, S. J. Bale, PhD, and J. J. DiGiovanna, MD.

• The degree of erythema and type of scale varies, and phenotypic overlap with lamellar ichthyosis is often observed; for example, larger, darker scales may be evident, especially on the lower extremities, and some patients have relatively small scales but little associated erythema.

Other Ichthyoses and Erythrokeratodermas

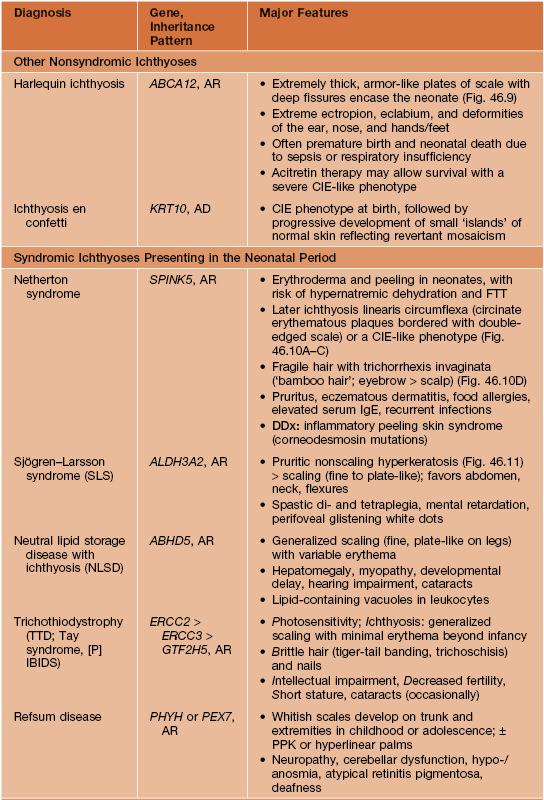

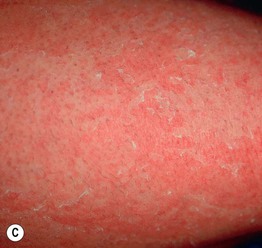

• Major features of several additional ichthyoses and erythrokeratodermas are summarized in Table 46.2 (Figs. 46.9–46.15); many other rare disorders of cornification with diverse cutaneous and extracutaneous manifestations also exist.

Table 46.2

Major features of other selected ichthyoses and erythrokeratodermas.

ABCA12, ATP-binding cassette, subfamily A, member 12; ABHD5, abhydrolase domain-containing 5; AD, autosomal dominant; ALDH3A2, aldehyde dehydrogenase 3A2; AR, autosomal recessive; CHILD, congenital hemidysplasia with ichthyosiform nevus and limb defects; CIE, congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma, EBP, emopamil binding protein (sterol isomerase); ERCC2/3, excision repair cross-complementing 2/3; FTT, failure to thrive; GJB2/3/4, gap junction β2/3/4 (encoding connexins 26/31/30.3); GTF2H5, general transcription factor IIH, polypeptide 5; KRT10, keratin 10; NSDHL, NAD(P)-dependent steroid dehydrogenase-like; PEX7, peroxisome biogenesis factor 7; PHYH, phytanoyl-CoA hydroxylase; PPK, palmoplantar keratoderma; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; SPINK5, serine protease inhibitor Kazal type 5; X-D, X-linked dominant.

Fig. 46.9 Harlequin ichthyosis. Severe hyperkeratosis with fissuring as well as eclabion and ectropion. Reproduced from Morillo M, Novo R, Torrelo A, et al. Feto arlequin. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 1999;90:185–187.

Fig. 46.10 Netherton syndrome. A Ichthyosis linearis circumflexa. Note the double-edged scale. B Generalized involvement with features of congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma. C Close-up showing ‘peeling’ quality of the scale. D Short, thin hair on the scalp, sparse eyebrows, and a lack of eyelashes. A, Courtesy, Gabriele Richard, MD, and Franziska Ringpfeil, MD.

Fig. 46.11 Sjögren–Larsson syndrome. Yellowish-brown hyperkeratosis, accentuated skin markings, and areas of scaling on the lower back and buttocks. Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

Fig. 46.12 CHILD syndrome. Note the sharp midline demarcation on the trunk. From Happle R, Mittag H, Kuster W. Dermatology 1995;191:210–216, with permission. Courtesy, Rudolph Happle, MD.

Fig. 46.13 Conradi–Hünermann–Happle syndrome. Erythroderma and linear streaks and whorls of hyperkeratosis. Courtesy, Rudolph Happle, MD.

Fig. 46.14 KID syndrome. A Erythematous plaques around the mouth have characteristic radial furrows. B Palmar keratoderma with a grainy surface. A, Courtesy, L. Russell, MD, and S. J. Bale, PhD; B, Courtesy, Gabriele Richard, MD, and Franziska Ringpfeil, MD.

For further information see Ch. 57. From Dermatology, Third Edition.