CHAPTER 2 Hysteroscopy

Historical Development

Bozzini was the first to look into the cavity of a hollow organ, the bladder, in 1805. This was achieved with long tubes assisted by external illumination. In 1853, Desormeaux made the first satisfactory endoscope, but it was Panteleoni who performed the first satisfactory hysteroscopy in 1869 (Panteleoni 1869). Inability to distend the uterus and lack of proper illumination caused poor visualization and lack of widespread acceptance until Lindemann renewed Rubin’s attempts to use carbon dioxide in the 1970s (Lindemann 1972).

Diagnostic Indications

Abnormal uterine bleeding

Menstrual abnormality is one of the most common reasons for referral to the gynaecological outpatient department. Menometrorrhagia, dysmenorrhoea and intermenstrual bleeding are the most common. After the menarche, such problems are usually dysfunctional, and hysteroscopy is rarely indicated. In postmenopausal patients, bleeding is a worrying symptom and warrants urgent attention as the patient is anxious to exclude endometrial cancer. Outpatient hysteroscopy offers rapid diagnosis and reassurance. In women of reproductive age, abnormal uterine bleeding can be associated with hormonal disturbances or pathology such as fibroids and polyps. Cervical polyps may be associated with endometrial polyps in 26.7% of patients (Stamatellos et al 2007), and exclusion of endometrial pathology is important.

Infertility

Hysteroscopy is a reliable method to detect and potentially treat submucous fibroids, endometrial polyps, intrauterine adhesions and endometritis. Congenital anomalies are infrequent but are associated with infertility. Abnormalities of the endometrium and organic intrauterine pathologies are important causes of failed in-vitro fertilization/embryo transfer cycles. A recent meta-analysis has shown potential benefits of performing pretreatment hysteroscopy in patients being referred for IVF (El-Toukhy et al 2008).

Recurrent miscarriage

The aetiology of recurrent miscarriage is poorly understood. Intrauterine pathology such as fibroids, polyps, Asherman’s syndrome or congenital abnormalities may be detected in up to 33% of infertile couples (Romano et al 1994). Implantation of an embryo over the septum or fibroid can also fail due to the poor blood supply in these parts of the uterus.

Chronic pelvic pain

Patients with chronic pain can pose a difficult challenge to the gynaecologist. Obstructive uterine anomaly may be associated in 40% of these patients (Schifrin et al 1973). Concomitant hysteroscopy may reveal polyps, fibroids, adhesions and septate uterus which may contribute to the patient’s symptoms.

Contraindications

Cervical stenosis

Patients who have a history of cervical surgery or difficult uterine entry in the past are at increased risk of cervical trauma, perforation and false passage during the performance of a hysteroscopy. Prostaglandins inserted 2 h before hysteroscopy may help to soften the cervix, allowing easy dilatation and entry into the uterine cavity, although the evidence is limited for their value in postmenopausal patients (Crane and Healey 2006).

Instrumentation

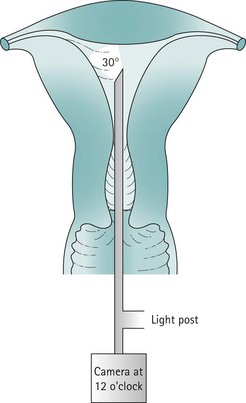

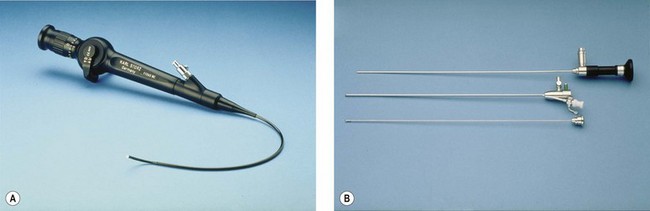

Inadequate instrumentation resulting in poor visualization and reduced safety is not only dangerous, but will potentially give erroneous results. Good-quality hysteroscopes, cameras and driver units are basic requirements for good visualization of the uterine cavity. Appropriate fluid monitoring systems and energy sources, such as laser or diathermy, are essential for operative hysteroscopy (Figure 2.1).

Before commencing any hysteroscopic procedure, one must ensure that the stack system (Figure 2.2) is fully functional. This includes the telescope, surgical instruments, camera drive unit, camera head, light source, light lead, monitor, electrosurgical generator and image recording equipment. If a simultaneous laparoscopy is required, two stack systems should be made available. It is essential to assemble the equipment to ensure that it works prior to use. The distension medium, suction machine, fluid measurement apparatus and connecting tubing must be checked. Fluid should be allowed to flow through the giving set to remove all air bubbles.

Optical systems

Rigid telescopes

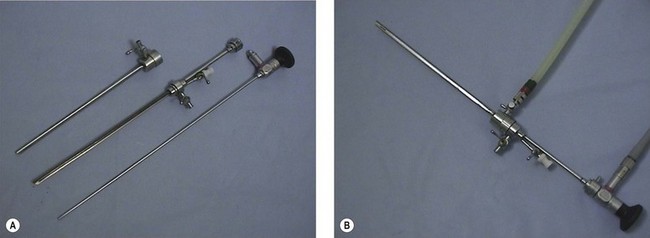

Panoramic hysteroscopy is performed with the help of a distension medium, and is common practice. The majority of hysteroscopists use rigid telescopes. Improved technology has allowed significant reduction in the outer diameter (as low as 2.5 mm, including the inflow sheath). The outer diameter of operative hysteroscopes using monopolar electrosurgery may be up to 10 mm. This includes the telescope with the working element, inflow sheath (inner) and outflow sheath (outer). Smaller-diameter operative scopes (Figure 2.3) measure 5 mm and consist of a 5 French operative channel communicating with the outflow sheath. This allows instruments of 5F diameter (e.g. the bipolar electrode, laser fibre, mechanical scissors and grasper) down the operative channel. The telescopes may be forward view (0°) or oblique view (angled scopes 12, 30, 70 or 90°).

Hysteroscopic sheaths

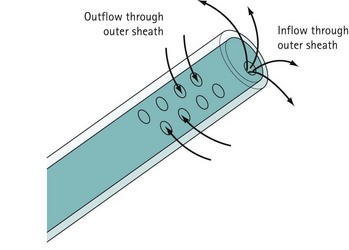

For diagnostic panoramic hysteroscopy, a single sheath for inflow is sufficient. This enables a smaller outer diameter and outpatient hysteroscopy without anaesthesia. Operative hysteroscopy needs separate sheaths for inflow and outflow. The inflow sheath carries the distension medium to the tip of the telescope, from where it is withdrawn via the outer sheath (Figure 2.4). Fluid circulates over the tip of the telescope to maintain a clear view.

Camera and stack system

The hysteroscopic image is visualized on a monitor with the help of a camera connected to a camera drive unit. The image clarity of a single chip camera is perfectly adequate. Special weighted cameras are available and facilitate orientation, but the same camera as is used for laparoscopy is equally appropriate. It is important to ‘white balance’ the camera system to ensure that the colours are displayed correctly (see Figure 2.2).

Technique of Diagnostic Hysteroscopy

Clinical anatomy of the uterus

The uterine cavity is flat in its anterior/posterior dimension as, when not distended, the anterior and posterior endometrial surfaces are apposed to each other. The cervical canal is essentially round, but once the cavity is entered, the lateral dimension widens until it is at its broadest at the fundus. The cavity extends laterally towards the tubal ostia (see Figure 2.1). The fundal dome may be flat, concave or convex on its interior surface. Indeed, a proportion of uteri have a pronounced fundal convexity, a so-called ‘arcuate deformity’.

Procedure

Inpatient/general anaesthetic

Potential problems include blood accumulating in the cavity and obscuring the view. This can occur during diagnosis when the seal between the hysteroscope and the cervix is very tight, preventing outflow of distension medium. The passage of a dilator 1 mm greater than the outer diameter of the hysteroscope allows flow and clearance of the contaminating blood. If a large polyp is present in the endometrial cavity, it is possible to inspect the cavity without realizing that the polyp is there because the polyp fills the cavity and the scope has been passed beyond the tip of the polyp before inspection begins (Figure 2.5). Suspicion should be aroused if the endometrial surfaces are different in colour, and careful inspection of the panoramic view of the cavity during insertion and removal of the scope will avoid missing a large polyp as the tip of it will be seen. A thorough examination of the uterine cavity should allow inspection of both tubal ostia. A record of this in the operation notes demonstrates that the operator has obtained a good view.

Hysteroscopy in outpatients

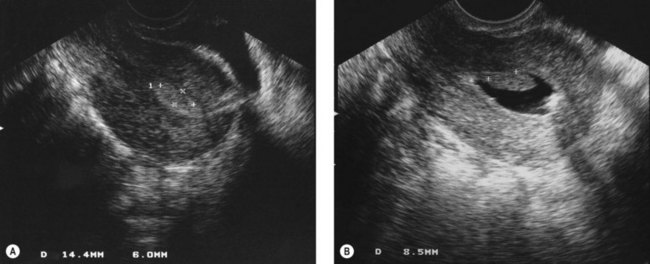

Provision of hysteroscopy combined with transvaginal ultrasound in outpatients provides a very efficient method of assessing women with pre- and postmenopausal bleeding. As mentioned above, many patients who require a hysteroscopy pose significant risk for general anaesthesia, and are best managed under local or no anaesthetic (Valli et al 1998). In addition, there are many advantages to the patient, including shorter time at the hospital and more rapid return to normal activity. There are also cost advantages to the hospital, as an outpatient clinic is clearly a less expensive environment than an operating theatre (Marsh et al 2004).

Choice of equipment

In reality, there are disadvantages and advantages of every system. Rigid autoclavable scopes tend to be of larger diameter, necessitating cervical dilatation in a proportion of cases. The advantage is clarity of view and a fore/oblique view allowing easier examination of the cornua. Flexible scopes are delicate and more expensive, but allow steering through the cervical canal and angulation to allow full inspection of the uterine cavity without any anaesthesia (Kremer et al 1998) (Figure 2.6A). Fibreoptic rigid scopes can be of very small diameter (1.2 mm in a 2.5-mm diagnostic sheath (Figure 2.6B). They are 0° so viewing of the cornua is more difficult, but they are relatively easy to pass through stenosed postmenopausal cervices, leading to a very low failure rate. The Versascope system provides a disposable sheath which can be distended by the passage of a 5 French instrument. This means that a change of sheath is not required to convert a diagnostic procedure into an operative procedure.

Hysteroscopy technique

In the outpatient setting, the authors favour a Cusco’s speculum to bring the cervix into view prior to introduction of the hysteroscope. This allows manipulation of the position of the cervix with the speculum as the scope is inserted to straighten the cervical canal. Rarely, it is necessary to grasp the cervix with a single-toothed tenaculum. Others use no speculum at all when performing vaginoscopy, and locate the cervix before inserting the hysteroscope into it. With the patient awake and the gynaecologist concentrating on passing the scope through a difficult cervix, the role of the attending nurse is paramount (Prather and Wolfe 1995). The nurse should have a good knowledge of the procedure, excellent communication skills and be able to maintain a rapport with the patient during the procedure. Preprocedure explanatory leaflets and a brief discussion help to reassure the patient, who often finds that the procedure causes less discomfort than is anticipated. Patients vary in their wish to see the television screen during the procedure, but the majority find it reassuring and helpful to be able to view the image of the uterine cavity. This also allows easier explanation of any pathology found.

Pathology Seen at Diagnostic Hysteroscopy

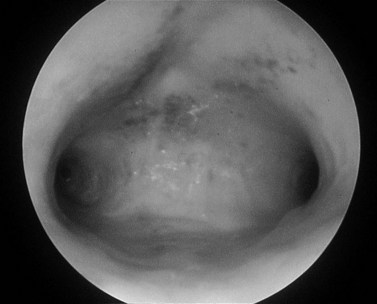

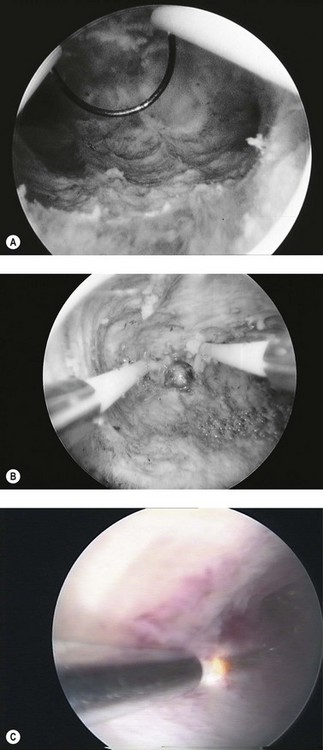

The diagnostic hysteroscopist should familiarize him-/herself with the normal appearances of the endometrium during the phases of the endometrial cycle and during the menopause (Figure 2.7). The endometrium should be assessed for colour, texture, vascularity and thickness. An impression of thickness can be gained by pressing the surface of the endometrium with the end of the hysteroscope. Postmenopausal atrophy is characterized by very thin pale endometrium, often accompanied by a ridged appearance.

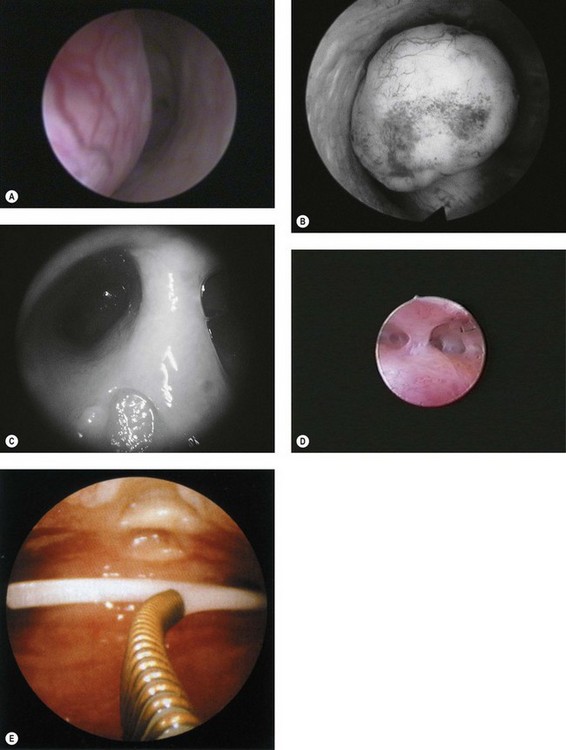

Endometrial polyps (Figure 2.8A) can vary considerably in appearance, and the observer should define the position and size of the base of the polyp to aid subsequent operative hysteroscopy. Fibroids (Figure 2.8B) have a characteristic whitish appearance, and often have clearly visible surface vessels. Submucous fibroids which bulge significantly into the uterine cavity may remain covered with endometrium, but do not often have an appearance similar to that of a fibroid polyp. An assessment should be made of the relative proportion of the fibroid which is bulging into the endometrial cavity, as this determines whether it is likely to be resectable during a single operative procedure or may require multiple attempts.

A uterine septum (Figure 2.8C) may be seen dividing the cavity into two halves, while intrauterine adhesions (Figure 2.8D) can lead to complete disruption of the cavity. An IUCD (Figure 2.8E) is the most common foreign body seen at diagnostic hysteroscopy.

Hyperplastic endometrium is thickened, often polypoid and has increased vascularity (Figure 2.9). Endometrial cancer is often friable, sometimes has a lobed appearance and may appear necrotic. It should be suspected in postmenopausal patients where only a poor view is obtained due to excessive bleeding. Tamoxifen causes a specific pattern of hyperplasia associated with a vesicular appearance.

Hysteroscopic Skills

The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) report on minimal access surgery categorized skill levels in training in both laparoscopy and hysteroscopy (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 1994). Hysteroscopic procedures were divided into three levels, with the first level covering diagnostic and simple procedures such as the removal of a foreign body (Box 2.1). The second level contains operative procedures, such as resection or ablation of the endometrium, and removal of polyps and fibroids. Advanced procedures (third level) include repeated resection or ablation, and treatment of extensive uterine synechiae. The RCOG established a subcommittee of the training committee to supervise training in minimal access surgery, and has since designed an advanced training module in benign gynaecological surgery which covers both diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy. It is mainly aimed at senior specialist registrars in obstetrics and gynaecology in their final 2 years of training. By completion of the module, ideally within 1 year, trainees are expected to have reached independent competence in performing both diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy. The trainee has to register with their preceptor and training programme director, who supervise and train the trainee in the practical aspects of outpatient diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy.

Box 2.1

Stratification of hysteroscopic procedures by level of training

Source: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) 1994 Report of Working Party on training in gynaecological endoscopic surgery, RCOG Press, London.

Training and learning curve

It has been shown that achieving the operative hysteroscopy skills has a steep learning curve. A recent survey of trainees registered for the hysteroscopy module showed that the 1-year target for obtaining the special skills module was difficult to achieve, with the most evident cause being the inability to acquire the expected operative hysteroscopy standard within the intended time (Shoukrey et al 2008).

Therapeutic strategy for benign disease

Instrumentation for operative hysteroscopy

Mechanical

Scissors and grasping forceps are passed down the operating channel of the hysteroscope, and can be used to cut the stalk of simple polyps, which are then grasped with forceps for removal (Figure 2.10). Lost foreign bodies such as IUCDs can be removed in a similar fashion.

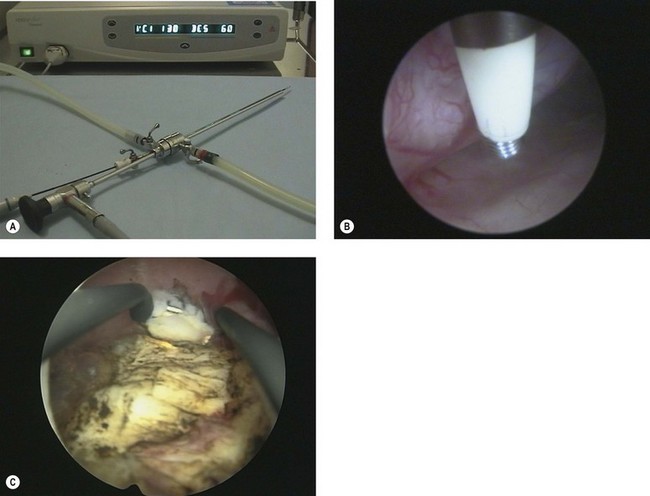

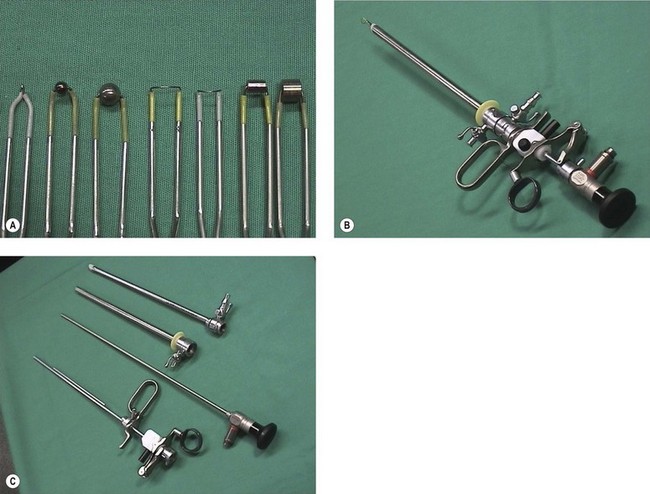

Monopolar electrical

Monopolar electrosurgery requires flow of radiofrequency electric current from the active tip of the instrument through the patient to the large surface area return plate. The electrical effect depends on both current density and the waveform provided by the generator. Simple instruments for use with monopolar diathermy include a polyp snare and simple electrodes, which can be passed down a 5 French operating channel. A dedicated continuous flow hysteroscope is required for more sophisticated operative instruments, including a resection loop, knife, rollerball and cylinder (Figure 2.11).

Figure 2.11 (A) Working elements for operative hysteroscopy. (B) Assembled resectoscope. (C) Components of resectoscope.

Trancervical resection of the endometrium (TCRE) is a popular technique for endometrial destruction in which the loop is used to cut away the prepared endometrium down to the myometrium. Figure 2.12A demonstrates the loop in use, and the transverse myometrial fibres can be seen clearly. Movement of the loop within the hysteroscope sheath and withdrawal of the scope itself allow long strips of endometrium to be resected. Removal of the tissue strips maintains a clear view. Most operators start with the posterior wall in order that the resected tissue strips do not obscure the working area. Considerable training is needed to ensure safe use of this technique. Difficult areas to treat include the cornua where the myometrium is thin, and the fundus where the resection loop has to be bent forwards in order to achieve a cutting effect in front of the tip of the hysteroscope. Cornual endometrium may be ablated with a rollerball and combined with resection of the remaining endometrium (Figure 2.12B). A Scandinavian study (Furst 2007) reported long-term follow-up of TCRE. This showed 80% patient satisfaction, and 20% of patients required hysterectomy at the end of 10 years.

The same instrument is used for resection of submucous fibroids and fibroid polyps, whilst the knife is employed for the treatment of Asherman’s syndrome and uterine septae. The resectoscope system is inexpensive as it uses reuseable electrodes, which are autoclavable. A careful watch must be kept on the fluid balance during the procedure, as overload of 1.5% glycine solution may lead to significant complications. More than 1 l of solution lost into the patient poses significant risk, and the procedure should be abandoned if such levels of fluid loss are significantly exceeded. Laser destruction is an alternative (Figure 2.12C).

Bipolar electrosurgery

Versapoint (Figure 2.13A) is a 5 French electrode. It requires a dedicated electrosurgery generator, which pulses the electrical energy through the saline irrigation medium from the active electrode tip to the larger return sleeve (Figure 2.13B). This creates a vapour pocket around the active electrode, and when tissue enters the vapour pocket, the high current density causes vaporization of the tissue. This device has been used for vaporizing fibroids and polyps. It is suitable for use under local anaesthetic, particularly in conjunction with the Versascope. The Versapoint resection system, a larger version using similar technology, is suitable for the removal of larger fibroids under general anaesthetic (Figure 2.13C). Bipolar electrodes appear to have a safer profile compared with monopolar electrodes because of the unchanged serum sodium. Irrigant consumption has been reported to be significantly higher in the two bipolar groups, without any side-effects during or after the procedure. Furthermore, the TCRE loop appears to be superior to the Versapoint loop in terms of operating time and amount of tissue removed (Berg et al 2009).

Endometrial destruction

The in-vivo studies of Duffy et al (1992) demonstrate that rollerball coagulation results in thermal necrosis to a depth of 3.3–3.7 mm. The depth of cut with a resection loop is 3–4 mm. Endometrial thickness, however, varies from 3 to 12 mm during the menstrual cycle. Therefore, satisfactory ablation can only be achieved if surgery is performed in the immediate postmenstrual phase. This leads to a shorter duration of surgery, greater ease of surgery and a high rate of postoperative amenorrhoea (Sowter et al 2001).

A national survey of the complications of endometrial destruction for menstrual disorders, the MISTLETOE study (Overton et al 1997), compared the different surgical techniques for endometrial destruction. Combined diathermy resection appeared safer than resection alone, but laser and rollerball ablation were the safest. Fibroids were associated with associated increased operative haemorrhage. Increasing operative experience was associated with fewer uterine perforations in the loop resection alone group, but had no effect on operative haemorrhage in any group. Cumulative failure rate at 1 year for combined resection and rollerball ablation was lowest at 15%, compared with 20% for resection or rollerball ablation alone, and 32% for laser ablation.

Comparison of endometrial destruction methods with hysterectomy revealed that they have less postoperative morbidity, shorter hospital stay, and quicker return to work, normal activity and sexual intercourse compared with hysterectomy, but patient satisfaction may be slightly higher following hysterectomy (Pinion et al 1994).

Non-operative methods of endometrial ablation and the use of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG IUS) for the treatment of menorrhagia have decreased the use of endometrial resection to treat dysfunctional uterine bleeding. The LNG IUS results in a smaller mean reduction in menstrual blood loss than TCRE and women are not as likely to become amenorrhoeic, but there is no difference in the rate of satisfaction with treatment (Lethaby et al 2005). In fact, in the meta-analysis of six randomized clinical trials, the efficacy of the LNG IUS in the management of heavy menstrual bleeding appears to have similar therapeutic effects to endometrial ablation up to 2 years after treatment (Kaunitz et al 2009).

Polypectomy and myomectomy

Fibroids under 2 cm in size can be resected in one sitting. For larger fibroids or those where more than half is intramural, a two-stage procedure may be necessary. In the first stage, the protruding portion of the fibroid is removed, followed by transhysteroscopic myolysis of the intramural portion (Donnez and Nisolle 1992). Subsequently, GnRH agonist therapy for 8 weeks shrinks the uterine cavity, extruding the intramural portion of the fibroid, which is then easily removed at the second stage to complete the myomectomy. Complete removal of the fibroid is associated with improved long-term results (Wamsteker et al 1993).

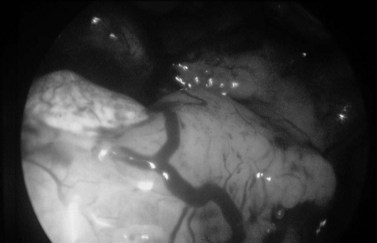

Uterine adhesions and septae

The division of dense uterine synechiae (Figure 2.14) and uterine septae requires considerable skill and is often performed under laparoscopic guidance, which ensures that thermal or electrical energy is not allowed to penetrate through the myometrium, damaging the adjacent bowel. Careful assessment prior to division of uterine septae is essential to prevent perforation at the fundus. The hysteroscopic appearances of a septate uterus and a uterus didelphys can be similar, and any attempt to resect the septum will clearly lead to disaster in the latter case. Careful ultrasound evaluation helps to differentiate between the two, but this has not yet replaced laparoscopic assessment. After adhesiolysis, an IUCD may be inserted for 3 months to prevent reformation of the adhesions. Similarly, postoperative hormone therapy may be initiated to help endometrial development and prevent further adhesion formation (Gordon et al 1995).

Operative hysteroscopy in the outpatient unit will be feasible in future. Authors have carried out transcervical resection procedures under local anaesthetic in daycare settings and have found a high level of patient satisfaction. A recent study has shown that this procedure is feasible with the availability of a mini-resectoscope (Papalampros et al 2009).

Treatment of the Endometrial Cavity without Intracavity Lesions

Second-generation techniques have shown comparable quality-of-life improvements and patient satisfaction rates with first-generation techniques, along with comparable success rates and complication profiles (Lethaby et al 2005).

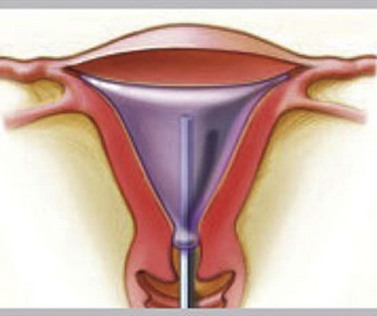

Thermal balloon ablation (Thermachoice, Gynaecare Ethicon Ltd, Somerville, NJ, USA)

The procedure does not require any dilatation and is feasible to perform in an outpatient setting (Andersson and Mints 2007, Clark and Gupta 2004). The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) has approved and validated the clinical safety and effectiveness of thermal ablation (see Figure 2.15).

A large multicentre observational study showed a significant reduction in the severity and duration of menstrual loss (Amso et al 1998). Thermachoice achieved a reduction in menstrual blood loss that was comparable with the first-generation techniques. In a long-term multicentre study, Thermachoice showed an 86% probability of avoiding a hysterectomy at 4–6-year follow-up (Amso et al 2003).

Other thermal balloons used in ablation are Cavaterm and Thermablate.

Free fluid ablation (Hydrothermablator, Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA)

In this technique, circulating hot saline solution is instilled into the uterus under direct hysteroscopic guidance. The saline is heated to 90°C and circulated for 10 min. A randomized controlled trial comparing Hydrothermablator with rollerball ablation (Townsend et al 2003) showed similar success rates as other second-generation devices (see Figure 2.16).

Impedance bipolar radiofrequency ablation (NovaSure, Novacept, Palo Alto, CA, USA)

Efficacy was reported in two randomized controlled trials and two case series (Abbott et al 2003). Amenorrhoea rates in these four studies ranged from 41% to 59% at 12 months, with higher amenorrhoea rates in the impedance controlled procedure. Continuing menorrhagia rates ranged from 3.9% to 14% at 12 months. There was also evidence to suggest that the majority of patients were satisfied following the procedure, and that quality of life had improved. At 3-year follow-up (Gallinat 2004), hysterectomy was avoided in 97% of women, 65% of whom were amenorrhoeic. Five-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial comparing NovaSure and Thermachoice endometrial ablation showed that bipolar radiofrequency ablation was superior to thermal ablation (Kleijn et al 2008).

Microwave endometrial ablation (MEA, Mircosulis Plc, Waterlooville, UK)

MEA was compared with TCRE in a well-designed randomized controlled trial (Cooper et al 1999), and was reported to have a significantly shorter mean operative time than TCRE (11.4 vs 15.0 min, P = 0.001), and comparable satisfaction and acceptability. Improved quality of life 1 year after treatment was reported for both groups. These results were sustained at 2-year follow-up. At 5-year follow-up, both techniques achieved significant and comparable improvements in menstrual symptoms and health-related quality of life (Cooper et al 2005). High rates of satisfaction with and acceptability of treatment were achieved following TCRE, but these rates were significantly lower than those following MEA. The long-term data after a further 5 years of follow-up, when combined with the trial’s operative findings and the known costs of both procedures, led the authors to conclude that MEA is a more effective and efficient treatment for heavy menstrual loss than TCRE (Sambrook et al 2009).

Complications of second-generation ablation devices

Minor immediate postoperative complications are common with second-generation ablation techniques and include pelvic pain, endometritis, urinary tract infection, nausea, vomiting, haematometra and pelvic inflammation. Reported serious complications included sepsis, adnexal/uterine necrosis, lower genital tract thermal injury and one death. Many of these resulted from non-compliance with the manufacturers’ instructions and other avoidable factors. A 2005 update of a Cochrane review (Lethaby et al 2005) concluded that equipment failure, nausea, vomiting and uterine cramping were more likely with second-generation ablation techniques but these were less likely to be associated with fluid overload, uterine perforation, cervical lacerations and haematometra than conventional ablation and resection techniques. Overall, they compared favourably with TCRE. Most of the second-generation devices (Cavaterm, Thermachoice, NovaSure, Cryoablation) require a relatively normal uterine cavity with a depth of less than 12 cm to complete the treatment satisfactorily. Free fluid ablation (Hydrothermablator) and MEA can be performed when the uterine cavity is irregular, although complete septate or bicornuate uteri are contraindications to undertaking the procedures. Pretreatment is not generally required.

Each device has its relative strengths and weaknesses, and no single device can be preferred over another in all circumstances. Clinicians should consider the safety and effectiveness figures, applicability to the outpatient environment, and evidence of quality-of-life improvement, applied on an individualized basis after full discussion with the patient and taking her preferences into account, as well as equipment availability and skill. Ongoing audit of a department’s success rates compared with the published figures ensures that patient selection and surgical strategy are appropriate. A survey of preferences and practices of endometrial ablation/resection for menorrhagia in UK showed that second-generation devices were preferred over first-generation devices. Thermal balloon ablation was the most favoured procedure (Deb et al 2008).

Hysteroscopic Sterilization

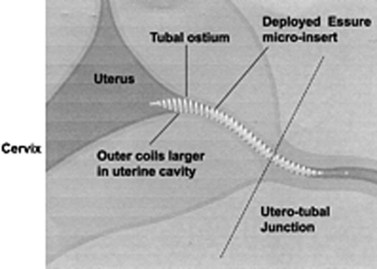

Essure system

A safe, simple and highly effective alternative to invasive procedures for interval tubal sterilization is now possible using a hysteroscopic approach. The Essure permanent birth control device (Conceptus Inc., San Carlos, CA, USA) is a combined metallic and fibre coil placed into the cornua hysteroscopically. Approval for its use has been granted by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and NICE. The dynamic outer coil made of nickel titanium alloy includes an inner flexible coil (stainless steel). The device is delivered into the fallopian tube in a tightly wound or ‘low profile’ position, where the two coils are tightly opposed and held in place with a wire before being released in the tubal lumen. The rapidly expanding outer coil fills the tubal lumen (Figure 2.17), anchoring the device in place. The polyethylene terephthalate fibres induce a benign localized tissue response consisting of inflammation and fibrosis, which leads to obliteration and occlusion of the tubal lumen in approximately 3 months (Valle et al 2002, Abbott 2007). The procedure is preferably done in the proliferative stage of the menstrual cycle. The procedure can be performed under local anaesthetic (paracervical nerve block with lidocaine 1%) in the outpatient setting (Sinha et al 2007). Hysteroscopy is then performed and tubal access is established. During insertion, the microinsert is maintained in a ‘wound down’ configuration by a release catheter, which is enclosed in a transparent delivery catheter. A guide wire is attached to the inner coil to facilitate device placement. The device is then deployed in the proximal tubal ostium with a single-handed release mechanism, and the guide wire is detached and withdrawn. Follow-up pelvic X-ray or hysterosalpingogram is recommended 3 months after insertion to confirm correct placement of the device or tubal occlusion. An occlusion rate of 100% has been shown at the end of 1 year with no pregnancies reported (Kerin et al 2003).

A comparison of the Essure permanent birth control device and laparoscopic sterilization (Duffy et al 2005) reported reduced hospital stay, less pain, better patient acceptability, higher patient satisfaction levels and fewer adverse events with the Essure procedure. A separate study of the direct costs associated with the Essure procedure compared with laparoscopic sterilization indicated that there is a cost advantage to Essure, although indirect costs were not considered in this model (Levie and Chudnoff 2005).

Alternative techniques and future developments

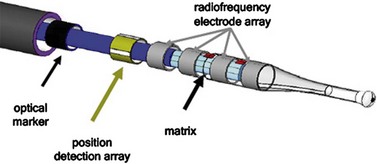

The Adiana procedure (Adiana Inc., Redwood City, CA, USA and Hologic, Inc., Bedford, MA, USA) involves bipolar ablation of the proximal fallopian tube followed by the placement of a synthetic matrix, subsequently leading to tubal occlusion. The device is currently being investigated in an FDA study in the USA, Australia and Mexico (Johns 2005) (Figure 2.18).

Complications of Hysteroscopy and Procedures

Uterine perforation

Uterine perforation occurs in approximately 1% of women undergoing endometrial ablation (Lewis 1994). It can happen due to entry of the scope into a false passage, when the scope is against the fundus, or while using the energy sources without visualizing the electrode. It is suspected if excessive bleeding is noted before the procedure is commenced, if the scope goes freely into the uterine cavity, or if the fluid distension pressure stays low or decreases suddenly. Rarely, a loop of bowel or omentum may be seen.

Late Complications

Haematometra and pyometra

Collection of blood in the uterine cavity followed by infection can occur after hysteroscopic surgery due to cervical stenosis. This can be prevented by avoiding ablation near the internal os. Occasionally, haematometra may occur after commencement of hormone replacement therapy (Dwyer et al 1991).

Newer Developments

KEY POINTS

Abbott J. Transcervical sterilization. Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007;19:325-330.

Abbott J, Hawe J, Hunter D, Garry R. A double-blind randomized trial comparing the Cavaterm(™) and the NovaSure(™) endometrial ablation systems for the treatment of dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Fertility and Sterility. 2003;80:203-208.

Andersson S, Mints M. Thermal balloon ablation for the treatment of menorrhagia in an outpatient setting. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2007;86:480-483.

Amso NN, Stabinsky SA, McFaul P, Blanc B, Pendley L, Neuwirth R. Uterine thermal balloon therapy for the treatment of menorrhagia: the first 300 patients from a multi-centre study. International Collaborative Uterine Thermal Balloon Working Group. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1998;105:517-523.

Amso NN, Fernandez H, Vilos G, et al. Uterine endometrial thermal balloon therapy for the treatment of menorrhagia: long-term multicentre follow up study. Human Reproduction. 2003;18:1082-1087.

Berg A, Sandvik L, Langebrekke A, Istre O. A randomized trial comparing monopolar electrodes using glycine 1.5% with two different types of bipolar electrodes (TCRis, Versapoint) using saline, in hysteroscopic surgery. Fertility and Sterility. 2009;91:1273-1278.

Clark TJ, Gupta JK. Outpatient thermal balloon ablation of the endometrium. Fertility and Sterility. 2004;82:1395-1401.

Crane JM, Healey S. Use of misoprostol before hysteroscopy: a systematic review. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 2006;28:373-379.

Cooper KG, Bain C, Parkin DE. Comparison of microwave endometrial ablation and transcervical resection of the endometrium for treatment of heavy menstrual loss: a randomised trial. The Lancet. 1999;354:1859-1863.

Cooper KG, Bain C, Lawrie L, Parking DE. A randomised comparison of microwave endometrial ablation with transcervical resection of the endometrium: follow-up at a minimum of five years. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2005;112:470-475.

Deb S, Flora K, Atiomo W. A survey of preferences and practices of endometrial ablation/resection for menorrhagia in the United Kingdom. Fertility and Sterility. 2008;90:1812-1817.

Donnez J, Nisolle M, Smets M, et al. Hysteroscopy in the diagnosis of specific disorder. In: Donnez J, Nisolle M, editors. An Atlas of Operative Laparoscopy and Hysteroscopy. London: Parthenon; 2001:403-409.

Donnez J, Nisolle M. Hysteroscopic surgery. Current Opinion in. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1992;4:439-446.

Duffy S, Marsh F, Rogerson L, et al. Female sterilisation: a cohort controlled comparative study of ESSURE versus laparoscopic sterilisation. BJOG: an International. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2005;112:1522-1528.

Dwyer N, Fox R, Mills M, Hutton J. Haematometra caused by hormone replacement therapy after endometrial resection. The Lancet. 1991;338:1205.

El-Toukhy M, Sunkara K, Coomarasamy A, Grace J, Khalaf Y. Outpatient hysteroscopy and subsequent IVF cycle outcome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reproductive Biomedicine Online. 2008;16:712-719.

Erian J. Endometrial ablation in the treatment of menorrhagia. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1994;101(Suppl 11):19-22.

Finikiotos G. Hysteroscopy: a review. Obstetrical and Gynecological Survey. 1994;49:273-283.

Furst SN. Ten year follow up of endometrial ablation for menorrhagia. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2007;86:334-338.

Gallinat A. NovaSure impedance controlled system for endometrial ablation: three-year follow-up on 107 patients. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2004;191:1585-1589.

Gordon AG, Lewis BV, De Cherney AH. Gynecologic Endoscopy, 2nd edn. London: Mosby Wolfe; 1995.

Johns D. Advances in hysteroscopic sterilization: report on 600 patients enrolled in the Adiana EASE pivotal trial. Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology. 2005;12(Suppl):S39-S40.

Kaunitz AM, Meredith S, Inki P, Kubba A, Sanchez-Ramos L. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and endometrial ablation in heavy menstrual bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2009;113:1104-1116.

Kleijn J, Engels R, Bourdrez P, Mol BWJ, Bongers MY. Five-year follow-up of a randomised controlled trial comparing NovaSure and ThermaChoice endometrial ablation. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2008;111:193-198.

Kerin JF, Cooper JM, Price T, et al. Hysteroscopic sterilization using a micro-insert device: results of a multicentre phase II study. Human Reproduction. 2003;18:1223-1230.

Kremer C, Barik S, Duffy S. Flexible outpatient hysteroscopy without anaesthesia: a safe, successful and well tolerated procedure. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1998;105:672-676.

Lethaby A, Hickey M, Garry R 2005 Endometrial destruction techniques for heavy menstrual bleeding. An update of Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2: CD001501. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 4: CD001501.

Lewis BV. Guidelines for endometrial ablation. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1994;101:470-473.

Levie MD, Chudnoff SG. Office hysteroscopic sterilization compared with laparoscopic sterilization: a critical cost analysis. Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology. 2005;12:318-322.

Lindemann HJ. The use of CO2 in the uterine cavity for hysteroscopy. International Journal of Fertility. 1972;17:221-225.

Marsh F, Kremer C, Duffy S. Delivering an effective outpatient service in gynaecology. A randomised controlled trial analysing the cost of outpatient versus daycase hysteroscopy. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2004;111:243-248.

Overton C, Hargreaves J, Maresh M. A national survey of the complications of endometrial destruction for menstrual disorders: the MISTLETOE study. Minimally invasive surgical techniques — laser, endothermal or endoresection. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1997;104:1351-1359.

Panteleoni D. On endoscopic examination of the cavity of the womb. The Medical Press and Circular. 1869;8:26-27.

Papalampros P, Gambadauro P, Papadopoulos N, Polyzos D, Chapman L, Magos A. A mini-resectoscope: a new instrument for office hysteroscopic surgery. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2009;88:227-230.

Pinion SB, Parkin DE, Amramovich DR, et al. Randomised trial of hysterectomy, endometrial laser ablation and transcervical endometrial resection for dysfunctional uterine bleeding. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 1994;309:979-983.

Prather C, Wolfe A. The nurse’s role in office hysteroscopy. Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Neonatal Nursing. 1995;24:813-816.

Romano F, Cicinelli E, Anastasio PS, Epifani S, Fanelli F, Galantino P. Sonohysteroscopy versus hysteroscopy for diagnosing endouterine abnormalities in fertile women. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 1994;45:253-260.

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG). Report of Working Party on training in gynaecological endoscopic surgery. London: RCOG Press; 1994.

Sambrook A, Bain C, Parkin D, Cooper K. A randomised comparison of microwave endometrial ablation with transcervical resection of the endometrium: follow-up at a minimum of 10 years. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2009;116:1033-1037.

Schifrin BS, Erez S, Moore JG. Teenage endometriosis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1973;116:973-980.

Shoukrey M, Fathulla BI, Samarrai T. Hysteroscopy training in the UK: the trainees’ perspective. Gynecological Surgery. 2008;5:213-219.

Sinha D, Kalathy V, Gupta JK, Clark TJ. The feasibility, success and patient satisfaction associated with outpatient hysteroscopic sterilisation. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2007;114:676-683.

Sowter MC, Singla AA, Lethaby A 2001 Pre-operative endometrial thinning agents before hysteroscopic surgery for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 1.

Stamatellos I, Stamatopoulos P, Bontis J. The role of hysteroscopy in the current management of the cervical polyps. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2007;276:299-303.

Townsend DE, Duleba AJ, Wilkes MM. Durability of treatment effects after endometrial cryoablation versus rollerball electroablation for abnormal uterine bleeding: two-year results of a multicenter randomised trial. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2003;188:699-701.

Valle RF, Cooper J, Kerin J. Hysteroscopic tubal sterilization with the Essure nonincisional permanent contraception. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2002;99(Suppl):11.

Valli E, Zupi E, Marconi D, Solima E, Nagar G, Romanini C. Outpatient diagnostic hysteroscopy. Journal of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists. 1998;5:397-402.

Wamsteker K, Emanuel MH, de Kruif JH. Transcervical hysteroscopic resection of submucous fibroids for normal uterine bleeding: results regarding the degree of intramural extension. Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1993;82:736-740.