Chapter 29 Hysterosalpingography

INTRODUCTION

Hysterosalpingography (HSG) is a radiographic procedure used to image the uterine cavity and demonstrate tubal patency by injecting radiographic contrast media through the cervix (Fig. 29-1). Along with documentation of ovulation and semen analysis, HSG is one of the fundamental infertility tests. The technique is easy to learn and perform, is relatively low-cost, and has an acceptable radiation exposure and few complications. More than 200,000 HSG procedures are performed annually in the United States.1

HISTORY

HSG was first performed in 1910 when Rindfleisch injected a bismuth solution transcervically followed by an abdominal X-ray. HSG has been the standard initial test for assessing the uterine cavity and fallopian tubes since Heuser used Lipiodol in 1925.2 Fluoroscopic control replaced static films in 1947.3 The procedure has remained essentially unchanged since then.

ACCURACY

HSG should be considered a screening test; as such, it should have a high sensitivity so as not to miss the opportunity to treat an abnormality but with a low false-positive rate to prevent unnecessary additional testing and treatments. The accuracy of an HSG is highly dependent on technique and interpretation. The technical quality of the HSG is important to limit misinterpretations (i.e., eliminating air bubbles that may be confused with a polyp or myoma or using inadequate contrast volume or injection pressure to demonstrate tubal patency). In one study 50 HSG films were reviewed by five reproductive endocrinologists. There was considerable variability in the interpretation as well as the recommended clinical management.4 In another study, three reproductive endocrinologists and three radiologists reviewed 50 HSGs on two occasions. The intrareader and inter-reader reliability was high for the detection of normal uterus and tubes, as well as tubal obstruction, but low for the detection of hydrosalpinges, uterine adhesions, pelvic adhesions, and salpingitis isthmica nodosa. Clinicians more reliably diagnosed hydrosalpinges and tubal obstruction; radiologists more reliably detected salpingitis isthmica nodosa and uterine adhesions.5

Diagnosing Uterine Cavity Abnormalities

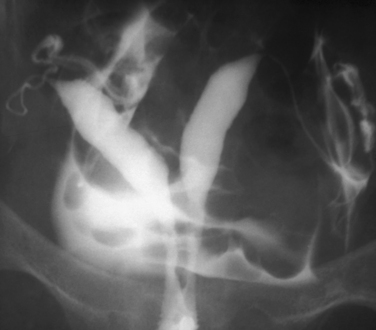

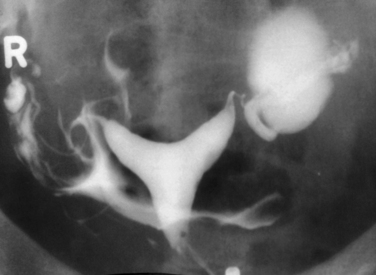

HSG has a high sensitivity but a low specificity for the diagnosis of uterine cavity abnormalities.6 HSG and diagnostic hysteroscopy performed on 336 infertile women showed that HSG had a sensitivity of 98% but a specificity of only 35% due to difficulties distinguishing between polyps and myomas. False-negative results were mild intrauterine adhesions of doubtful clinical significance.7 Thus, HSG fulfills the requirements as a good first-line screening test for revealing abnormalities of the uterine cavity, although any abnormalities found will likely need further evaluation to make a definitive diagnosis. Sonohysterography or diagnostic hysteroscopy can distinguish between polyps and submucous myomas, which appear similar on HSG (Fig. 29-2). A uterine septum and a bicornuate uterus cannot be differentiated on an HSG (Fig. 29-3). Evaluation of the external fundal contour by laparoscopy, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or three-dimensional ultrasonography is required to make a definitive diagnosis. The arcuate uterus has a mild convex fundal margin and is a normal variant. Extrinsic compression from an intramural fundal myoma may give a similar appearance and is easily recognized on routine transvaginal ultrasonography.

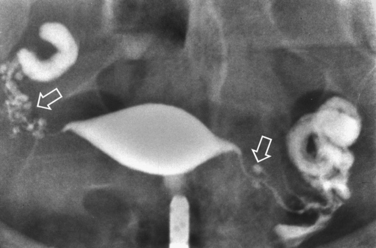

Other conditions visualized on HSG are adhesions, changes caused by diethylstilbestrol (DES), and adenomyosis. Adhesions appear as irregular filling defects and may be very mild or completely obliterate the cavity (Fig. 29-4). DES was used from the 1940s up to 1971 as prophylaxis for spontaneous abortions. The classic appearance associated with in utero DES exposure is a hypoplastic T-shaped cavity. (Fig. 29-5). Adenomyosis can occasionally be diagnosed by HSG as a cavity with shaggy borders (Fig. 29-6). The sensitivity for detecting this condition is unknown because it is uncommon in younger women and is definitely diagnosed histologically after hysterectomy.

Diagnosing Tubal Abnormalities

An evidence-based study found HSG to be “a valid and accurate diagnostic test to be applied in a general population of subfertile couples to assess tubal patency but an unreliable test for diagnosing tubal occlusion.” Tubal blockage on HSG is not confirmed by laparoscopy in up to 62% of patients, but if HSG suggests patent tubes, tubal blockage is highly unlikely. Laparoscopy is needed to confirm or exclude tubal occlusion on HSG.8 It should be noted that laparoscopy is not the perfect gold standard; 2% of patients with bilateral tubal occlusion subsequently conceived spontaneously.9 One study noted that 60% of patients with proximal tubal occlusion on HSG were patent on repeat HSG 1 month later.10

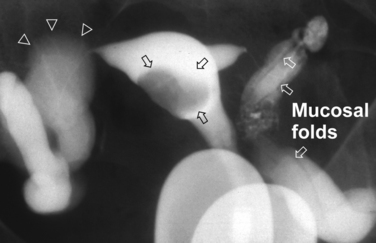

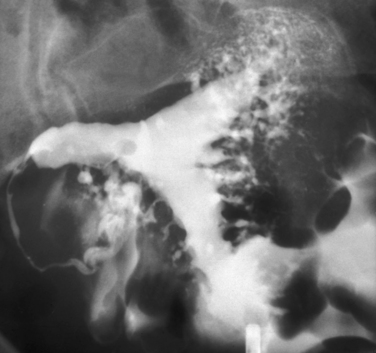

Surprisingly, hydrosalpinges may be both overdiagnosed and underdiagnosed by HSG. They may be only mildly dilated with preservation of mucosal folds or massively dilated with complete loss of the normal intratubal architecture (Fig. 29-7). HSG can also diagnose salpingitis isthmica nodosa. This condition, which predisposes to tubal occlusion and ectopic pregnancy, is similar to adenomyosis of the uterus in that there are diverticuli from the mucosa into the muscularis (Fig. 29-8). HSG is also not an ideal test for diagnosing pelvic adhesions because it detects them in only half of the cases in which they are present.2 Adhesions are usually diagnosed on HSG by the presence of loculated spill of contrast medium (Fig. 29-9).

INDICATIONS

HSG is part of the basic infertility workup and is normally required in every patient.11 It is still the first-line technique for excluding anatomic defects in the uterine cavity and documenting tubal patency in infertility patients. A 1994 survey of board-certified reproductive endocrinologists in the United States reported that 96% obtained an HSG as part of the basic infertility workup.12 In addition to its role in assessing the uterus and tubes, HSG may have a therapeutic effect.

Hysterosalpingography has also been the mainstay for diagnosing uterine cavity abnormalities in women with recurrent pregnancy loss. Such abnormalities have been reported in 15% to 27% of these patients. The most common anomaly is the septate uterus; surgical correction improves the live birth rate from 3% to 20% to 70% to 90%.13 Because tubal status is not an issue with these patients, HSG may be replaced with sonohysterography.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Active Pelvic Infection

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is an uncommon but potentially serious complication of HSG. Active cervicitis, endometritis, or salpingitis are absolute contraindications to performing an HSG. Cervical cultures for gonorrhea and chlamydia, a white blood cell count, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate should be obtained to rule out an active infection in patients with adnexal tenderness. They may also be considered in patients with a history of prior PID.

Severe Iodine Allergy

Patients with a history of severe iodine allergy may elect to forgo HSG in favor of diagnostic laparoscopy and hysteroscopy or sonohysterosalpingography. However, the risk of a severe reaction with HSG is small because the volume of contrast (most of which escapes vaginally) is small and it is not injected intravascularly. If a decision is made to proceed with HSG in patients with known iodine allergy, a nonionic water-soluble media such as Hexabrix (ioxaglate), Isovue 370 (iopamidol), or Omnipaque (iohexol) should be used because the incidence of iodine allergy is lower with them.2 Patients with severe iodine allergy should be premedicated with prednisone 50mg administered 13 hours before HSG and diphenhydramine 50mg 1 hour before. In a study in 563 patients with a history of anaphylactic reactions to iodine contrast treated with this protocol, there were fewer than 10 reactions, none life threatening.14

Endometrial Carcinoma

It is felt to be prudent to avoid performing HSG in known or suspected cases of endometrial carcinoma for fear of disseminating tumor cells and worsening the prognosis for survival. Studies on using HSG for the diagnosis and follow-up of endometrial carcinoma noted that injecting contrast media under low pressure is unlikely to disseminate tumor cells and that it is doubtful that shed cells have the potential for independent metastasis.15 The 5-year survival in endometrial carcinoma patients evaluated with HSG was not significantly different in those who had positive washings after the procedure versus those who did not. Venous or lymphatic extravasation also failed to influence survival rates.16

Pregnancy

HSG is scheduled immediately after menses to prevent performing the procedure in the presence of an unrecognized pregnancy due to the concerns of disrupting the pregnancy as well as radiation exposure. Before the advent of pregnancy testing and ultrasonography, HSG was performed specifically to diagnose pregnancy, with no untoward effects.2 HSG during inadvertent pregnancy is uncommonly reported. In a recent case report the calculated dose to the embryo was 3.7 mGy. The authors state that the teratogenic risk with less than 20 mGy during the first trimester does not justify pregnancy termination.17 The possibility of spontaneous abortion should be discussed with the patient.

TECHNICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Analgesia

Unfortunately, most patients experience uterine cramping during the HSG, but the entire procedure usually only lasts about 3 minutes and the discomfort resolves rapidly at the end of the procedure. A prospective, double-blind, randomized, controlled trial comparing 1 g of acetominophen to placebo taken 30 minutes before HSG found no significant difference in mean pain scores during or 24 hours after the procedure.18 Several studies noted that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) did provide significant analgesia for HSG.19–21

Two randomized, placebo-controlled studies found no difference with intrauterine anesthetics delivered before the HSG. Patients in both studies also received an NSAID, which may have decreased pain enough to mask any beneficial effect of the anesthetic.22,23 There are no references on the use of paracervical blockade for HSG.

Oil-soluble versus Water-soluble Contrast Media

The water-soluble media and oil-soluble media camps have been arguing the relative merits of their favored contrast for decades; as yet there is no clear winner. Water-soluble media offers better image quality because the higher density oil-soluble media tends to obscure fine details in the uterus and tubal mucosal folds. Also, because water-soluble media dissipates quickly, there is no need for delayed films, whereas 1- to 24-hour delayed films are necessary with oil-soluble media. Oil-soluble media also carries increased risks for oil embolism and granuloma formation. Proponents of oil-soluble media counter that water-soluble media causes increased pain on peritoneal spill, although it is mild and very transient. Water-soluble media with lower osmolality may cause less irritation and discomfort.2 The procedure should be performed with the smallest volume of contrast possible to provide the needed information. The biggest argument in favor of oil-soluble media is that it has higher postprocedure pregnancy rates. Most still advocate water-soluble media because it provides better uterine and ampullary mucosal detail and has no serious secondary effects.3,6

Types of Cannulas

Rigid metal cannulas have been the standard device for performing HSG because they are inexpensive, reusable, and readily available. A balloon catheter can be employed in rare cases when cervical stenosis or an inadequate cervical seal prevent completion of the study with the rigid cannula. In addition to the cost of the disposable balloon catheter, it is more difficult to manipulate the uterus compared to a rigid cannula with a tenaculum. Also, the balloon obscures the lower uterine segment. One study reported that the balloon catheter caused significantly greater pain after the procedure.24 However, a randomized study found that HSG performed with a balloon catheter required less contrast and fluoroscopy time, produced less patient discomfort, and was easier for senior residents to perform. It has the additional advantage of allowing the clinician to perform immediate selective salpingography and transcervical tubal catheterization for proximal tubal occlusion without the need to replace the cannula or reschedule the patient.25 A randomized study comparing the rigid cannula to a cervical vacuum cup cannula reported that HSG performed with the disposable vacuum device was quicker to perform, required less contrast and fluoroscopy time, caused less patient discomfort, and was easier for senior residents to perform.26

Technique

A right or left marker should be placed on the film cassette for orientation. Fluoroscopy is initiated with the cannula tip aligned at the lower end of the frame and the pelvis observed for any abnormalities that may affect the interpretation of the study. In the absence of any obvious abnormalities, a scout film only increases radiation exposure without providing additional significant information.27 Contrast media is then injected slowly both for patient comfort as well as to delineate any subtle uterine filling defects that may not be visible after complete filling, particularly with the denser oil-soluble contrast media. A film may be taken during initial filling. If a filling defect is suspected to be an air bubble, the patient can be rotated on her side (defect side down). A polyp or myoma will remain stationary, whereas a bubble will rise to the elevated side.

The injection of contrast continues while watching the fallopian tubes opacify and spill. Only 5 to 10 mL are usually required to complete the study. Water-soluble contrast media will be seen to outline loops of bowel immediately, but a delayed film is needed to confirm free spill of oil-soluble media. One- and 24-hour delayed films were equivalent for determining tubal status, but the 1-hour interval was less accurate for diagnosing peritubal adhesions.28 Patients should be observed for a few minutes for bleeding and signs of vasovagal or allergic reactions.

SPECIAL CASES

Proximal Tubal Occlusion

Although bilateral proximal tubal occlusion is usually indicative of anatomic pathology, unilateral proximal tubal occlusion is frequently transient due to spasm of the uterotubal ostium or to plugging by mucus, debris, or air bubbles. Unilateral proximal tubal occlusion is found in 10% to 24% of patients, but 16% to 80% are patent on repeat HSG or laparoscopy with chromotubation.29 Increasing the hydrostatic pressure will establish patency in a high percentage of patients, 72% in one large series.10

In one study, rotating the patient such that the proximal tubal occlusion faces down establishes patency in 63%. The authors suggested that this effect was due to unkinking the tube, but dislodging an air bubble is also possible. Rotating the patient so the proximal tubal occlusion side faces up never resulted in patency.29 The use of antispasmodic agents such as glucagon to prevent proximal tubal occlusion due to spasm has also been recommended, but the literature contains only anecdotal reports.

Management of Proximal Tubal Occlusion

As noted, 60% of patients with proximal tubal occlusion on HSG were shown to be patent on repeat HSG 1 month later.10 Therefore, we do not attempt to correct the problem at the initial HSG.

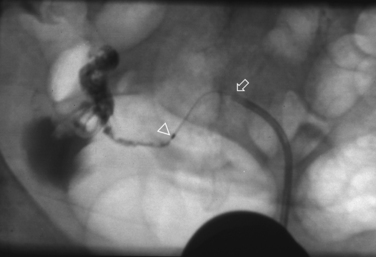

Selective salpingography may be attempted if a repeat HSG at least 1 month later confirms persistent proximal tubal occlusion. The repeat HSG is performed with a balloon catheter under intravenous conscious sedation and a #5 French catheter advanced through it and wedged in the cornua under fluoroscopic guidance. Contrast media is then injected, establishing patency in one third of the tubes.3

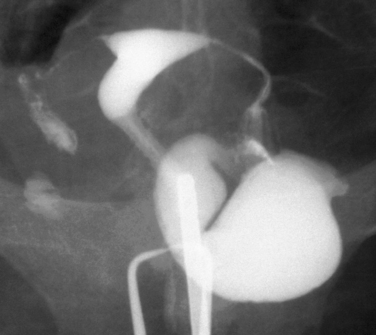

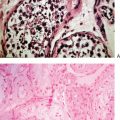

Tubal cannulation may be attempted in the two thirds of the tube that remained occluded during selective salpingography. A flexible guidewire is then passed through the tubal ostium and, if successful, a #3 French catheter is advanced over the wire and contrast media is injected (Fig. 29-10). The procedure is successful more than 85% of the time.2 Excision of the proximal tubes in cases of failed tubal cannulation revealed salpingitis isthmica nodosa, chronic salpingitis, or fibrosis in 93%.30 The conception rate within 6 to 12 cycles is 30% to 40% with a 5% to 10% ectopic rate.2 Approximately one third of the opened tubes reocclude.2,3

The radiation dose ranged from 25 cGy for unilateral or bilateral selective salpingography to 78.5 gGy for bilateral tubal cannulation.31 Tubal perforation has been reported in 3% to 11% but was always innocuous.32 If laparoscopy is indicated, tubal cannulation can be performed by directing the guidewire and inner catheter into the tubal ostium through the operating cannel of a hysteroscope. Success rates in terms of patency, pregnancy, reocclusion, and perforation are nearly identical.

RISKS

Vasovagal Reactions

Less than 5% of patients may experience some of the features of a vasovagal reaction, with light-headedness, pallor, sweating, bradycardia, and hypotension.15 It usually resolves spontaneously within a few minutes. Patients are kept supine on the table with their legs elevated until all symptoms have subsided. Atropine 0.4mg may be administered subcutaneously in the very rare more profound and protracted cases.

Infection

A 1983 study reported that 1.4% of patients undergoing HSG developed PID and all had tubal dilation. The overall frequency of PID in women with dilated tubes was 11%.33 In this study, patients with a history of PID or a positive chlamydia titer were administered doxycycline 100 b.i.d. for 5 days beginning 2 days before the HSG. If dilated tubes were unexpectedly noted on HSG, the same 5-day regimen of doxycycline was initiated right after the HSG. No cases of PID were observed in women who received antibiotic treatment. The current American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommendation is that no prophylactic antibiotics be given in the absence of a history of PID unless hydrosalpinges are noted.34 It may be safer and more cost-effective to proceed directly to laparoscopy in patients with a history of PID, prior treatment for gonorrhea or chlamydia, or a positive chlamydia antibody titer. Not only will this eliminate the risk of post-HSG infection, but these patients are also significantly more likely to have pelvic pathology requiring surgical correction.

Radiation

The radiation dose depends on the patient’s size, position of the ovaries, the machine used, the distance between the ovaries and the machine, the duration of fluoroscopy, the number of images taken, and the degree of image magnification.2 Every effort should be made to reduce the fluoroscopy time and limit the number of images taken. Generally, no more than two spot films are necessary, and the typical study requires less than 10 seconds of fluoroscopy time.35

The average ovarian dose is 2.8 to 4.6 mGy.36 Nearly 75% of the total dose was attributable to capturing film images and the remainder to fluoroscopy.37 Using a digital system reduced the dosage sixfold compared with analog systems.36 The patient-effective dose from an average HSG is less than half of the annual background radiation dose in the United States. The risk38 for an anomaly in a future embryo was estimated to be 27 × 10−6 and the risk for a fatal cancer in patients at highest risk (under 30 years old) was 145 × 10−6.

Granuloma Formation

Water-soluble media is absorbed within minutes, whereas oil-soluble contrast media can persist for months or even years in cases of obstructed tubes, which can be problematic during future abdominal radiographic studies. Persistence of the contrast has the potential to induce a foreign body reaction (granuloma) in the uterus or tubes. There are no data on the prevalence of granulomas or whether they are detrimental to fertility.2 Water-soluble media should certainly be selected in patients at risk for distal obstruction, but granulomas seldom occur when the tubes are normal.3

Oil Embolism

Intravasation, the entrance of contrast medium into the myometrial veins and lymphatics, occurs in up to 7% of patients (Fig. 29-11).39 Risk factors for intravasation include tubal obstruction, recent uterine surgery, uterine malformations, misplaced cannula, and excessive injection pressure or quantity of media.2 The intravasated contrast quickly passes through the uterine and ovarian veins to the lungs. Water-soluble media is rapidly dissipated and has an extremely low potential to cause embolic symptoms or side effects, whereas nearly all of the reported embolic complications, including deaths, resulted from use of oil-soluble media.

Figure 29-11 Intravasated contrast fills the myometrial veins and lymphatics and extends up the pelvic veins.

Approximately 20% of patients with oil-soluble media intravasation develop symptoms, including chest pain, cough, dyspnea, light-headedness, confusion, headache and, rarely, cardiorespiratory failure and death. Patients may also have hematuria, hemoptysis, hemolysis, fever, leukocytosis, pneumonia, lipuria, and medium in peripheral vessels, especially the brain. This has rarely been a problem in recent years due to the universal use of fluoroscopy, which allows for the immediate recognition of intravastion and termination of the procedure.2 In fact, there have been no deaths from oil-soluble media embolism since 1947, when fluoroscopy replaced spot films.3

FERTILITY ENHANCEMENT

A major purported advantage of HSG is an increased postprocedure pregnancy rate. Two meta-analyses confirmed that pregnancy rates were significantly higher in patients who received oil-soluble media.40,41 There are numerous possible mechanisms by which this occurs: the more viscous oil-soluble media may result in higher hydrostatic pressures to dislodge intraluminal plugs and break down adhesions. It may also have a bacteriostatic effect, stimulate ciliary action, inhibit sperm phagocytosis by peritoneal mast cells, and emulsify tubal debris.3

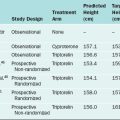

However, even with water-soluble media, 29% conceived after HSG, with a fourfold higher pregnancy rate during the first 3 months after the test.42 A recent large multicenter trial, which randomized patients to water-soluble media, oil-soluble media, or oil-soluble media following water-soluble media, found no differences in live birth rates.43 This study was included in the current Cochrane analysis, which came to the following conclusions: HSG with oil-soluble media significantly increased the pregnancy rate by an odds ratio (OR) of 3.57 versus no intervention. There were no randomized trials to assess water-soluble media versus no intervention. There were no significant differences between the pregnancy rates with oil-soluble media and water-soluble media.41

As early as 1980, it was suggested that the tubes should be flushed with oil-soluble media after confirming patency with water-soluble media to reduce the complications associated with oil-soluble media while retaining its presumed higher therapeutic effect.44 Subsequent randomized studies found no advantage to this practice.3,41,45

ALTERNATIVE PROCEDURES

Chlamydia Antibody Testing

Half of PID cases are due to Chlamydia trachomatis, and 50% to 80% of those are asymptomatic. There was a marked association between the chlamydia antibody titer and the likelihood of tubal damage.46 A meta-analysis showed that chlamydia antibody testing by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay or immunofluorescense is comparable to HSG in the diagnosis of tubal patency but provides no details on the anatomy of the uterus or tubes.47 Although chlamydia antibody testing is not going to replace HSG as the first-line screening test to evaluate the uterine cavity and tubes, it may have a role in helping to decide which patients with a normal HSG should undergo a diagnostic laparoscopy because patients with positive titers may have adnexal adhesions and subtle tubal disease not detected by HSG.

Sonohysterography and Sonohysterosalpingography

Sonohysterography (SHG) is a quick, painless office procedure accomplished by injecting saline solution into the uterine cavity through an intrauterine insemination catheter while performing transvaginal ultrasonography. SHG, HSG, and hysteroscopy are equivalent for the evaluation of the uterine cavity. In addition, SHG provides information on the myometrium and the ovaries, avoids the discomfort and radiation of HSG, and is less expensive than hysteroscopy.48 SHG should be used instead of HSG when evaluation of the tubes is not necessary, such as in cases of recurrent pregnancy loss or infertility where tubal status had been previously documented by laparoscopy.48,49

Sonohysterosalpingography, also called hysterosalpingo-contrast sonography (HyCoSy), utilizes a transcervical balloon catheter to inject either saline solution with air bubbles, sonicated albumin, or Echovist-200, a galactose solution with microbubbles, under transvaginal ultrasound guidance to document tubal patency. Similar to SHG, it has the advantages of being performed in the office, avoiding radiation exposure, and visualizing the myometrium and ovaries. A randomized study comparing HyCoSy and HSG to laparoscopy with chromotubation reported that both imaging techniques were comparable in terms of diagnostic accuracy, patient pain, and preference. The authors concluded that there appeared to be no strong arguments either to replace HSG by HyCoSy or to reject the use of HyCoSy.50 Of concern, another study noted that of women diagnosed with tubal occlusion by HyCoSy, 47% were shown to be patent on subsequent HSG. Severe pain or vasovagal symptoms occurred in 21% of patients undergoing HyCoSy versus none with HSG. Finally, HyCoSy with Echovist-200 costs 10 times more than HSG.51 A recent HyCoSy study also reported that HSG had a higher sensitivity than HyCoSy for tubal occlusion and 59% of the patients experienced moderate to severe pain with HyCoSy. The authors note that HyCoSy does not image the entire tube and that HSG gives a more accurate location of tubal obstruction.52 HyCoSy cannot yet replace HSG.11

MRI and Three-dimensional Ultrasonography

HSG using gadolinium contrast and MRI was proposed with the advantages of avoiding radiation and the ability to visualize the myometrium and ovaries. However, a pilot study noted that the tubes were very poorly visualized.53 MRI and three-dimensional ultrasonography should be limited to distinguishing between septate and bicornuate uteri noted on HSG.

Radionuclide Scanning

Radionuclide HSG has been evaluated as a more functional approach to tubal infertility diagnosis than conventional patency tests. Technetium-99m labeled human serum albumin microsphere particles were placed in the cervical canal and images taken for up to 5 hours. Radionuclide HSG investigation is not able to predict fertility potential because the same percentage of women conceived, with and without demonstrated patency.54 Additionally, it provides no information on the anatomy of the uterus or tubes.

Diagnostic Laparoscopy and Hysteroscopy

Bypassing HSG in favor of diagnostic laparoscopy and hysteroscopy to assess the uterus and tubes is probably more cost-effective in patients with pelvic pain, adnexal masses, or other indications for surgery, as well as a history of PID or prior pelvic surgery. These patients are much more likely to have pelvic pathology requiring surgical treatment. It is debatable when and if laparoscopy should be recommended when the HSG is normal. Of 265 infertility patients with a normal HSG, only 7% were felt to have clinically significant disease.55 Pain symptoms or positive chlamydia antibody titers could help to better select patients for laparoscopy. Hysteroscopy is not justified if the HSG is normal because HSG has a high sensitivity for uterine cavity abnormalities, and false negatives are of doubtful clinical significance.7,56,57

Transvaginal hydrolaparoscopy (TVHL) is a relatively new procedure that can be performed in the office without anesthesia. It involves placing a small rigid scope through a colpotomy incision and floating the bowel out of the pelvis with warm saline solution. It can be combined with hysteroscopy to assess the uterus as well as with chromotubation and salpingoscopy. A study of 23 patients who underwent both TVHL with office hysteroscopy and HSG reported that the former had lower pain scores but that the test took more than twice as long to complete.58

Transvaginal hydrolaparoscopy followed by laparoscopy was performed in patients with unexplained infertility. Findings were concordant in 80%, and discordant findings were not considered to have clinical consequence. The authors concluded that laparoscopy could have been avoided in 93%.59 TVHL combined with office hysteroscopy has the potential to replace HSG as the initial screening test for infertility patients. In addition to evaluating the endometrial cavity and tubal patency, it affords a view of the pelvic cavity, even if not as accurate or complete as laparoscopy. The addition of salpingography may yield further information regarding the ampullary lumen. TVHL and hysteroscopy may also be better tolerated than HSG. More studies are needed before HSG can be displaced as the mainstay study for infertility.

Salpingoscopy and Falloposcopy

Salpingoscopy is performed by introducing a small scope through the fimbria up to the ampullary–isthmic junction at laparoscopy. The tube is examined by injecting saline solution while withdrawing the scope. The primary indication for salpingoscopy is as a prognostic factor for pregnancy after neosapingostomy for hydrosalpinges. Patients with a normal salpingoscopy had significantly higher pregnancy and lower ectopic pregnancy rates than patients with abnormal salpingoscopic findings. Salpingoscopy was superior to HSG for predicting pregnancy.60 Studies comparing HSG and salpingoscopy noted that HSG had a 45% false-negative and a 30% false-positive rate for diagnosing tubal disease.60,61 Interest in salpingoscopy has been renewed because it can be performed during TVHL.62 However, only 26.4% to 64% of the tubes could be visualized by salpingoscopy during TVHL.63,64

Falloposcopy, unlike salpingoscopy, examines the entire tube in antegrade fashion with a 0.5-mm diameter scope in a 0.8-mm Teflon sheath. The scope is guided into the uterotubal ostium through the operating channel of a hysteroscope or with a linear everting catheter.65,66 Fluid is injected through the sheath to displace the endosalpinx off the lens and improve visualization. A classification of normal and abnormal falloscopic findings was reported in 1992 and showed that it had some prognostic value. The tubes could be cannulated 85% to 95% of the time in large series, but the distal tube becomes too wide beyond the ampullary–isthmic junction for the entire width of the lumen to be visualized.11 No images were of sufficient quality to describe the entire tubal mucosa in detail. Technical problems such as “white out” and catheter kinking also limit the usefulness of this method in routine clinical practice.67 Tubal perforation rates up to 10% have been reported, all with severe fibrotic proximal tubal occlusion and without adverse sequelae.68 The technique never gained acceptance.

SUMMARY

1 Karande VC, Pratt DE, Rabin DS, Gleicher N. The limited value of hysterosalpingography in assessing tubal status and fertility potential. Fertil Steril. 1995;63:1167-1171.

2 Soules MR, Mack LA. Imaging of the reproductive tract in infertile women: Hysterosalpingography, ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging. In: Keye WR, Chang RJ, Rebar RW, Soules MR, editors. Infertility Evaluation and Treatment. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1995:300-329.

3 Pinto AB, Hovsepian DM, Wattanakumtornkul S, Pilgram TK. Pregnancy outcomes after fallopian tube recanalization: Oil-based versus water-soluble contrast agents. J Vasc Intervent Radiol. 2003;14:69-74.

4 Glatstein IZ, Sleeper LA, Lavy Y, et al. Observer variability in the diagnosis and management of the hysterosalpingogram. Fertil Steril. 1997;67:233-237.

5 Renbaum L, Ufberg D, Sammel M, et al. Reliability of clinicians versus radiologists for detecting abnormalities on hysterosalpingogram films. Fertil Steril. 2002;78:614-618.

6 Ubeda B, Paraira M, Alert E, Abuin RA. Hysterosalpingography: Spectrum of normal variants and nonpathologic findings. Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177:131-135.

7 Preutthipan S, Linasmita V. A prospective comparative study between hysterosalpingography and hysteroscopy in the detection of intrauterine pathology in patients with infertility. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2003;29:33-37.

8 Evers JL, Land JA, Mol BW. Evidence-based medicine for diagnostic questions. Semin Reprod Med. 2003;21:9-15.

9 Mol BW, Collins JA, Burrows EA, et al. Comparison of hysterosalpingography and laparoscopy in predicting fertility outcome. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:1237-1242.

10 Dessole S, Meloni GB, Capobianco G, et al. A second hysterosalpingography reduces the use of selective technique for treatment of a proximal tubal obstruction. Fertil Steril. 2000;73:1037-1039.

11 Hedon B, Dechaud H, Boulot P, Laffargue F. Critical evaluation of the fallopian tube. In: Kempers RD, Cohen J, Haney AF, Younger BJ, editors. Fertility and Reproductive Medicine. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science; 1998:61-70.

12 Glatstein IZ, Harlow BL, Hornstein MD. Practice patterns among reproductive endocrinologists: Further aspects of the infertility evaluation. Fertil Steril. 1997;70:263-269.

13 Alborzi S, Dehbashi S, Parsanezhad ME. Differential diagnosis of septate and bicornuate uterus by sonohysterography eliminates the need for laparoscopy. Fertil Steril. 2002;78:176-178.

14 Greenberger PA, Patterson R, Radin RC. Two pretreatment regimens for high-risk patient receiving radiographic contrast media. JAMA. 1979;241:2813-2815.

15 Hunt RB, Siegler AM. Hysterosalpingography: Techniques & Interpretation. Chicago: Year Book Medical Publishers, 1990.

16 DeVore GR, Schwartz P, Morris J. Hysterography: A 5–year follow-up in patients with endometrial carcinoma. Obstet Gynecol. 1982;60:369.

17 Jongen VH, Collins JM, Lubbers JA, van Selm M. Unsuspected early pregnancy at hysterosalpingography. Fertil Steril. 2001;76:610-611.

18 Elson EM, Ridley NT. Paracetamol as a prophylactic analgesic for hysterosalpingography: A double blind randomized controlled trial. Clinical Radiology. 2000;55:675-678.

19 Owens OM, Schiff I, Kaul AF, et al. Reduction of pain following hysterosalpingogram by prior analgesic administration. Fertil Steril. 1985;43:146-148.

20 Lorino CO, Prough SG, Aksel S, et al. Pain relief in hysterosalpingography. A comparison of analgesics. J Reprod Med. 1990;35:533-536.

21 Peters AA, Witte EH, Damen AC, et al. Pain relief during and following outpatient curettage and hysterosalpingography: A double blind study to compare the efficacy and safety of tramadol versus naproxen. Cobra Research Group. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1996;66:51-56.

22 Costello MF, Horrowitz S, Steigrad S, et al. Transcervical intrauterine topical local anesthetic at hysterosalpingography: A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Fertil Steril. 2002;78:1116-1122.

23 Frishman GN, Spencer PK, Weitzen S, et al. The use of intrauterine lidocaine to minimize pain during hysterosalpingography: A randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:1261-1266.

24 Varpula M. Hysterosalpingography with a balloon catheter versus a cannula: Evaluation of patient pain. Radiology. 1989;172:745-747.

25 Tur-Kaspa I, Seidman DS, Soriano D, et al. Hysterosalpingography with a balloon catheter versus a metal cannula: A prospective, randomized, blinded comparative study. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:75-77.

26 Cohen SB, Wattiez A, Seidman DS, et al. Comparison of cervical vacuum cup cannula with metal cannula for hysterosalpingography. BJOG. 2001;108:1031-1035.

27 Okpala OC, Adinma JI, Ikechebelu JI. Assessment of the value of preliminary films at hysterosalpingography. West African J Med. 2000;19:105-106.

28 Reshef E, Daniel WW, Foster JC, et al. Comparison between 1-hour and 24-hour follow-up radiographs in hysterosalpingography using oil based contrast media. Fertil Steril. 1989;52:753-755.

29 Hurd WW, Wyckoff ET, Reynolds DB, et al. Patient rotation and resolution of unilateral cornual obstruction during hysterosalpingography. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:1275-1278.

30 Letterie GS, Sakas EL. Histology of proximal tubal obstruction in cases of unsuccessful tubal canalization. Fertil Steril. 1991;56:831.

31 Papaioannou S, Afnan M, Coomarasamy A, et al. Long term safety of fluoroscopically guided selective salpingography and tubal catheterization. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:370-372.

32 Dessole S, Farina M, Rubattu G, et al. Side effects and complications of sonohysterosalpingography. Fertil Steril. 2003;80:620-624.

33 Pittaway DE, Winfield AC, Maxson W, et al. Prevention of acute pelvic inflammatory disease after hysterosalpingography: Efficacy of doxycycline prophylaxis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1983;147:623-626.

34 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists: Antibiotic Prophylaxis for Gynecologic Procedures. ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 23, 2001.

35 Richmond JA. Hysterosalpingography. In: Lobo RA, Mishell DR, Paulson RJ, Shoup D, editors. Mishell’s Textbook of Infertility, Contraception, and Reproductive Endocrinology. 4th ed. Boston: Blackwell Science; 1997:567-579.

36 Gregan AC, Peach D, McHugo JM. Patient dosimetry in hysterosalpingography: A comparative study. Brit J Radiol. 1998;71:1058-1061.

37 Fernandez JM, Vano E, Guibelalde E. Patient doses in hysterosalpingography. Brit J Radiol. 1996;69:751-754.

38 Perisinakis K, Damilakis J, Grammatikakis J, et al. Radiogenic risks from hysterosalpingography. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:1522-1528.

39 Nunley WCJ, Bateman BG, Kitchin JD, Pope TLJ. Intravasation during hysterosalpingography using oil-base contrast medium—a second look. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;70:309-312.

40 Watson A, Vandekerckhove P, Lilford R, et al. A meta-analysis of the therapeutic role of oil soluble contrast media at hysterosalpingography: A surprising result? Fertil Steril. 1994;61:470-477.

41 Johnson N, Vandekerckhove P, Watson A, et al. Tubal flushing for subfertility. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 2, 2005. CD003718.

42 Cundiff G, Carr BR, Marshburn PB. Infertile couples with a normal hysterosalpingogram. Reproductive outcome and its relationship to clinical and laparoscopic findings. J Reprod Med. 1995;40:19-24.

43 Spring DB, Barkan HE, Pruyn SC. Potential therapeutic effects of contrast materials in hysterosalpingography: A prospective randomized clinical trial. Kaiser Permanente Infertility Work Group. Radiology. 2000;214:53-57.

44 DeCherney AH, Kort H, Barney JB, DeVore GR. Increased pregnancy rate with oil-soluble hysterosalpingography dye. Fertil Steril. 1980;33:407-410.

45 Steiner AZ, Meyer WR, Clark RL, Hartmann KE. Oil-soluble contrast during hysterosalpingography in women with proven tubal patency. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:109-113.

46 Thomas K, Coughlin L, Mannion PT, Haddad NG. The value of Chlamydia trachomatis antibody testing as part of routine infertility investigations. Hum Reprod. 2000;15:1079-1082.

47 Mol BW, Dijkman B, Wertheim P, et al. The accuracy of serum chlamydial antibodies in the diagnosis of tubal pathology: A meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 1997;67:1031-1037.

48 Goldberg JM, Falcone T, Attaran M. Sonohysterographic evaluation of uterine abnormalities noted on hysterosalpingography. Hum Reprod. 1997;12:2151-2153.

49 Brown SE, Coddington CC, Schnorr J, et al. Evaluation of outpatient hysteroscopy, saline infusion hysterosonography, and hysterosalpingography in infertile women: A prospective, randomized study. Fertil Steril. 2000;74:1029-1034.

50 Dijkman AB, Mol BW, Van der Veen F, et al. Can hysterosalpingocontrastsonography replace hysterosalpingography in the assessment of tubal subfertility? Eur J Radiol. 2000;35:44-48.

51 Stacey C, Bown C, Manhire A, Rose D. HyCoSy—as good as claimed? Brit J Radiol. 2000;73:133-136.

52 Exacoustos C, Zupi E, Carusotti C, et al. Hysterosalpingo-contrast sonography compared with hysterosalpingography and laparoscopic dye pertubation to evaluate tubal patency. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2003;10:367-372.

53 Unterweger M, De Geyter C, Frohlich JM, et al. Three-dimensional dynamic MR-hysterosalpingography: A new, low invasive, radiation-free and less painful radiological approach to female infertility. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:3138-3141.

54 Lundberg S, Wramsby H, Bremmer S, et al. Radionuclide hysterosalpingography is not predictive in the diagnosis of infertility. Fertil Steril. 1998;69:216-220.

55 al-Badawi IA, Fluker MR, Bebbington MW. Diagnostic laparoscopy in infertile women with normal hysterosalpingograms. J Reprod Med. 1999;44:953-957.

56 Cohen LS, Valle RF. Role of vaginal sonography and hysterosonography in the endoscopic treatment of uterine myomas. Fertil Steril. 2000;73:197-204.

57 Hourvitz A, Ledee N, Gervaise A, et al. Should diagnostic hysteroscopy be a routine procedure during diagnostic laparoscopy in women with normal hysterosalpingography? Reprod Biomed Online. 2002;4:256-260.

58 Cicinelli E, Matteo M, Causio F, et al. Tolerability of the mini-panendoscopic approach (transvaginal hydrolaparoscopy and minihysteroscopy) versus hysterosalpingography in an outpatient infertility investigation. Fertil Steril. 2001;76:1048-1051.

59 Watrelot A, Nisolle M, Chelli H, et al. Is laparoscopy still the gold standard in infertility assessment? A comparison of fertiloscopy versus laparoscopy in infertility. Results of an international multicentre prospective trial: The FLY (Fertiloscopy-LaparoscopY) study. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:834-839.

60 Henry-Suchet J, Tesquiter L, Pez JP, Loffredo V. Prognostic value of tuboscopy vs. hysterosalpingography before tuboplasty. J Reprod Med. 1984;29:609-612.

61 Puttemans P, Brosens I, Delattin P, et al. Salpingoscopy versus hysterosalpingography in hydrosalpinges. Hum Reprod. 1987;2:535-540.

62 Watrelot A, Dreyfus JM, Cohen M. Systematic salpingoscopy and microsalpingoscopy during fertiloscopy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2002;9:453-459.

63 Gordts S, Campo R, Rombauts L, Brosens I. Transvaginal salpingoscopy: An office procedure for infertility investigation. Fertil Steril. 1998;70:523-526.

64 Fujiwara H, Shibahara H, Hirano Y, et al. Usefulness and prognostic value of transvaginal hydrolaparoscopy in infertile women. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:186-189.

65 Kerin JF, Pearlstone AC, Surrey ES. Tubal microendoscopy: Salpingoscopy and falloposcopy. In: Keye WR, Chang RJ, Rebar RW, Soules MR, editors. Infertility Evaluation and Treatment. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1995:372-386.

66 Pearlstone AC, Surrey ES, Kerin JF. The linear everting catheter: A nonhysteroscopic, transvaginal technique for access and microendoscopy of the fallopian tube. Fertil Steril. 1992;58:854-857.

67 Lundberg S, Rasmussen C, Berg AA, Lindblom B. Falloposcopy in conjunction with laparoscopy: Possibilities and limitations. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:1490-1492.

68 Kerin JF, Pearlstone AC, Surrey ES. Cannulation of the fallopian tube and falloposcopy: Difficulties and complications. In: Corfman RS, Diamond MP, DeCherney A, editors. Complications of Laparoscopy and Hysteroscopy. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific; 1993:223-235.

69 Goldberg J, Falcone T. Effect of DES on reproductive function. Fertil Steril. 1999;72:1-7.

70 Goldberg JM, Falcone T. Congenital malformations of the female genital tract: Diagnosis and management. In: Gidwani G, Falcone T, editors. Müllerian Anomalies: Reproduction, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999:177-204.