Chapter 580 Hypofunction of the Ovaries

Hypofunction of the ovaries can be either primary or central in etiology. It may be caused by congenital failure of development, postnatal destruction (primary or hypergonadotropic hypogonadism), or lack of central stimulation by the pituitary and/or hypothalamus (secondary or tertiary hypogonadotropic hypogonadism). Primary ovarian insufficiency (hypergonadotropic hypogonadism), which is also termed premature ovarian failure, is characterized by the arrest of normal ovarian function before the age of 40 yr. Mutations of certain genes could result in primary ovarian insufficiency. Hypofunction of the ovaries due to lack of central stimulation (hypogonadotropic hypogonadism) can be associated with other processes such as multiple pituitary hormone deficiencies and some chronic diseases. Table 580-1 details the etiologic classification of ovarian hypofunction.

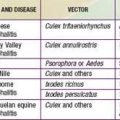

Table 580-1 ETIOLOGIC CLASSIFICATION OF OVARIAN HYPOFUNCTION

HYPOGONADOTROPIC HYPOGONADISM

HYPERGONDADOTROPIC HYPOGONADISM

580.1 Hypergonadotropic Hypogonadism in the Female (Primary Hypogonadism)

Turner Syndrome

Turner described a syndrome consisting of sexual infantilism, webbed neck, and cubitus valgus in adult females (Chapter 76). Ullrich described an 8 yr old girl with short stature and many of the same phenotypic features. The term Ullrich-Turner syndrome is frequently used in Europe but rarely used in the USA. The condition is defined as the combination of the characteristic phenotypic features accompanied by complete or partial absence of the second X chromosome with or without mosaicism.

Clinical Manifestations

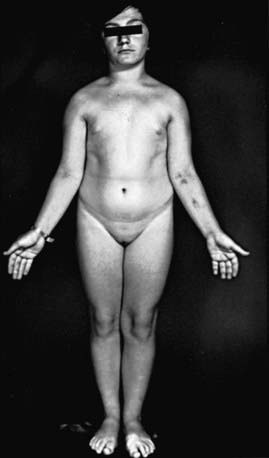

Many patients with Turner syndrome are recognizable at birth because of a characteristic edema of the dorsa of the hands and feet and loose skinfolds at the nape of the neck. Low birthweight and decreased length are common (Chapter 76). Clinical manifestations in childhood include webbing of the neck, a low posterior hairline, small mandible, prominent ears, epicanthal folds, high arched palate, a broad chest presenting the illusion of widely spaced nipples, cubitus valgus, and hyperconvex fingernails. The diagnosis is often first suspected at puberty when breast development fails to occur.

Short stature, the cardinal finding in virtually all girls with Turner syndrome, may be present with little in the way of other clinical manifestations. The linear growth deceleration begins in infancy and young childhood, gets progressively more pronounced in later childhood and adolescence, and results in significant adult short stature. Sexual maturation fails to occur at the expected age. Among untreated patients with Turner syndrome, the mean adult height is 143-144 cm in the USA and most of northern Europe, but 140 cm in Argentina and 147 cm in Scandinavia (Fig. 580-1). The height is well correlated with the midparental height (average of the parents’ heights). Specific growth curves for height have been developed for girls with Turner syndrome.

In patients with 45,X/46,XX mosaicism, the abnormalities are attenuated and fewer; short stature is as frequent as it is in the 45,X patient and may be the only manifestation of the condition other than ovarian failure (see Fig. 580-1).

45,X/46,XY Gonadal Dysgenesis

Children with a female phenotype present no problem in gender of rearing. Patients who are only slightly virilized are usually assigned a female gender of rearing before a diagnosis is established. Patients with ambiguity of the genitals are readily often clinically indistinguishable from patients with various types of 46,XY disorders of sex development (46,XY DSD). In many but not all instances, these children are best reared as females; the short stature, the ease of genital reconstruction, and the predisposition of the gonad to the development of malignancy may favor this choice. In some patients followed to adulthood, the putative normal testis proves to be dysgenetic with eventual loss of Leydig and Sertoli cell function (Chapter 577). In an analysis of 22 Australian patients with mixed gonadal dysgenesis, no significant associations or correlations were found between internal and external phenotypes or endocrine function and gonadal morphologic features. The sex of rearing was determined by the appearance of the external genitals. In 11 patients, basal and human chorionic gonadotropin–stimulated testosterone levels were lower than in control subjects.

Noonan Syndrome

Girls with Noonan syndrome show certain anomalies that also occur in girls with 45,X Turner syndrome, but they have normal 46,XX chromosomes. The most common abnormalities are the same as those described for males with Noonan syndrome (Chapter 577.1). The phenotype differs from Turner syndrome in several respects. Short stature is one of the cardinal signs of this syndrome. Mental retardation is often present, the cardiac defect is most often pulmonary valvular stenosis or an atrial septal defect rather than an aortic defect, normal sexual maturation usually occurs but is delayed by 2 yr on average, and premature ovarian failure has been reported. Growth hormone therapy is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for use in Noonan syndrome patients with short stature.

Other Ovarian Defects

Galactosemia, particularly the classical form of the disease, usually results in ovarian damage, beginning during intrauterine life. Levels of FSH and luteinizing hormone (LH) are elevated early in life. Ovarian damage may be due to deficient uridine diphosphate-galactose (Chapter 81). The Denys-Drash syndrome, caused by a WT1 mutation, can result in ovarian dysgenesis.

Hypergonadotropic hypogonadism has been postulated to also occur because of the resistance of the ovary to both endogenous and exogenous gonadotropins (Savage syndrome). This condition occurs also in women with POF. Antiovarian antibodies or FSH receptor abnormalities may cause this condition. Mutation of the FSH receptor gene has been reported as an autosomal recessive condition (Chapter 576). A few females with 46,XX chromosomes presenting in primary amenorrhea with elevated gonadotropin levels were found to have inactivating mutations of the LH receptor gene. This suggests that LH action is needed for normal follicular development and ovulation. Other genetic defects associated with ovarian failure include mutations in FOXL2, GNAS, CYP17, and CYP19. Some data also suggest that mutations within the gene encoding transcription factor SF-1 are associated with early ovarian failure.

Aittomaki K, Lucena JLD, Pakarinen P, et al. Mutation in the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor gene causes hereditary hypergonadotropic ovarian failure. Cell. 1995;82:959-968.

Berdahl LD, Wenstrom KD, Hanson JW. Web neck anomaly and its association with congenital heart disease. Am J Med Genet. 1995;56:304-307.

Betterle C, Volpato M. Adrenal and ovarian autoimmunity. Eur J Endocrinol. 1998;138:16-25.

Binder G, Kock A, Wajs E, et al. Nested polymerase chain reaction study of 53 cases with Turner syndrome: is cytogenetically undetected Y mosaicism common? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80:3532-3536.

Bondy CA. Care of girls and women with Turner syndrome: a guideline of the Turner syndrome study group. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:10-25.

Calvo RM, Asuncion M, Telleria D, et al. Screening for mutations in the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein and steroidogenic factor-1 genes, and in CYP11A and dosage-sensitive sex reversal-adrenal hypoplasia gene on the X chromosome, gene-1 (DAX-1), in hyperandrogenic hirsute women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:1746-1749.

Carel JC, Mathivon L, Gendrel C, et al. Near normalization of final height with adapted doses of growth hormone in Turner syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:1462-1466.

Chang HJ, Clark RD, Bachman H. The phenotype of 45,X/46,XY mosaicism: an analysis of 92 prenatally diagnosed cases. Am J Hum Genet. 1990;46:156-167.

De la Chesnayae E, Canto P, Ulloa-Aguirre A, et al. No evidence of mutations in the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor gene in Mexican women with 46,XX pure gonadal dysgenesis. Am J Med Genet. 2001;98:125-128.

De Vos M, Devroey P, Fauser BC. Primary ovarian insufficiency. Lancet. 2010;376:911-918.

Doherty E, Pakarinen P, Tiitinen A, et al. A novel mutation in the FSH receptor inhibiting signal transduction and causing primary ovarian failure. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:1151-1155.

Gicquel C, Gaston V, Cabrol S, et al. Assessment of Turner syndrome by molecular analysis of the X chromosome in growth-retarded girls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:1472-1476.

Gravholt CH, Fedder J, Naeraa RW, et al. Occurrence of gonadoblastoma in females with Turner syndrome and Y chromosome material: a population study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:3199-3202.

Hoek A, Schoemaker J, Drexhage HA. Premature ovarian failure and ovarian autoimmunity. Endocr Rev. 1997;18:107-134.

Holland CM. 47,XXX in an adolescent with premature ovarian failure and autoimmune disease. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2001;14:77-80.

Iezzoni JC, Kap-Herr CV, Golden W, et al. Gonadoblastomas in 45,X/46,XY mosaicism. Am J Clin Pathol. 1997;108:197-203.

Lin AE, Lippe B, Rosenfeld RD. Further delineation of aortic dilation, dissection, and rupture in patients with Turner syndrome. Pediatrics. 1998;102:e12.

Linssen WH, van den Bent MJ, Brunner HG, et al. Deafness, sensory neuropathy, and ovarian dysgenesis: a new syndrome or a broader spectrum of Perrault syndrome? Am J Med Genet. 1994;51:81-82.

Lourenco D, Brauner R, Lin L, et al. Mutations in NRSA1 associated with ovarian insufficiency. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1200-1210.

Mazzanti L, Cacciari E, Bergamaschi R, et al. Pelvic ultrasonography in patients with Turner syndrome: age-related findings in different karyotypes. J Pediatr. 1997;131:135-140.

Melner MH, Feltus FA. Autoimmune premature ovarian failure—endocrine aspects of a T-cell disease: review. Endocrinology. 1999;140:3401-3403.

Migeon BR, Luo S, Jani M, et al. The severe phenotype of females with tiny ring X chromosomes are associated with inability of these chromosomes to undergo X inactivation. Am J Med Genet. 1994;55:497-504.

Nelson LM. Primary ovarian insufficiency. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:606-614.

Pasquino AM, Passeri F, Pucarelli I, et al. Spontaneous pubertal development in Turner syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:1810-1813.

Patwardham AJ, Brown WE, Bender BG, et al. Reduced size of the amygdala in individuals with 47,XXY and 47,XXX karyotypes. Am J Med Genet. 2002;114:93-98.

Quigley CA, Crowe BJ, Anglin DG, et al. Growth hormone and low dose estrogen in Turner syndrome: results of a United States multi-center trial to near-final height. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:2033-2041.

Rongen-Westerlaken C, Corel K, van den Broeck J, et al. Reference values for height, height velocity and weight in Turner syndrome. Acta Paediatr. 1997;86:937-942.

Rosenfeld R, Devine N, Julius Hunold J, et al. Treatment of girls with Turner syndrome (TS) with very low doses of estrogen beginning at 12 years enhances the growth-promoting effect of GH. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:6424-6430.

Ross JL, Roeltgen D, Feuillan P, et al. Use of estrogen in young girls with Turner syndrome. Neurology. 2000;54:164-170.

Schorry EK, Lovell AM, Milatovich A, et al. Ullrich-Turner syndrome and neurofibromatosis-1. Am J Med Genet. 1996;66:423-425.

Seashore MR, Cho S, Desposito F, et al. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Genetics: health supervision for children with Turner syndrome. Pediatrics. 1995;96:1166-1173.

Sempe M, Hansson Bodallaz C, Limoni C. Growth curves in untreated Ullrich-Turner syndrome: French reference standards 1–22 years. Eur J Pediatr. 1996;155:862-869.

Sybert VP. Cardiovascular malformations and complications in Turner syndrome. Pediatrics. 1998;101:E11.

Telvi L, Lebar A, DelPino O, et al. 45,X/46,XY mosaicism: report of 27 cases. Pediatrics. 1999;104:304-308.

Thibaud E, Ramirez M, Brauner R, et al. Preservation of ovarian function by ovarian transposition performed before pelvic irradiation during childhood. J Pediatr. 1992;121:880-884.

580.2 Hypogonadotropic Hypogonadism in the Female (Secondary Hypogonadism)

Etiology

Hypopituitarism

Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism is less common than hypergonadotropic hypogonadism. The latter condition underlies polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS; Stein-Leventhal syndrome; Chapter 546).

Merke DP, Tajima T, Baron J, et al. Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism in a female caused by an X-linked recessive mutation in the Dax1 gene. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1248-1252.

Murphy KG. Kisspeptins: regulators of metastasis and the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. J Neuroendocrinol. 2005;17:519-525.

Topaloglu AK, Reimann F, Guclu M, et al. TAC3 and TACR3 mutations in familial hypogonadotropic hypogonadism reveal a key role for neurokinin B in the central control of reproduction. Nat Genet. 2009;41:354-358.

Tsai P-S, Gill JC. Mechanisms of disease: insights into X-linked and autosomal-dominant Kallman syndrome. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2008;2:160.