69 Hypertensive Crisis

• Hypertension is a common, serious disease that is often undertreated.

• Hypertensive urgency or emergency is the presence of elevated risk for or actual end-organ dysfunction caused by the elevated blood pressure. Severely elevated blood pressure itself does not create an emergency.

• A hypertension evaluation is, primarily, the assessment of key organ systems.

• Hypertensive emergencies are decompensated processes requiring immediate stabilization.

• Hypertensive urgencies occur in patients with underlying target organ disease and no evidence of current compounded dysfunction but who have higher risk for near-term complications.

• Severely elevated blood pressure alone does not usually require aggressive therapy.

• Therapy should be determined by the underlying pathology.

• Frequently, the most important intervention is establishing good primary care.

Epidemiology

Worldwide, as many as 1 billion people suffer from hypertension, and about 7.5 million deaths per year are attributed to hypertension.1 Approximately 28.9% of individuals in the United States, or 85 million, are affected by hypertension.2,3 Less than two thirds of U.S. adults with hypertension are aware of their condition, less than half are currently undergoing treatment of it, and only 30% have their blood pressure under control, yet of those seen in hypertensive crisis, it has been previously diagnosed in most of them and they have inadequate blood pressure control.4 Although hypertensive crisis develops in only 1% of patients with hypertension, some studies have found that hypertensive emergencies account for 28% of all patient visits to the emergency department (ED) for medical complaints, 21% of which were hypertensive urgencies and 6.4% were hypertensive emergencies.5 Preeclampsia (pregnancy-induced hypertension with proteinuria) occurs in 7% of pregnancies and most frequently in primigravidas.4 Uninsured populations, who receive a disproportionate amount of their care in EDs, have a higher prevalence and poorer control of elevated blood pressure. In inner-city public EDs, as many as 20% of the adult population have been found to have blood pressure higher than 140/90 mm Hg.5–7 As an important cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and renal failure modifiable risk factor, a modest 5–mm Hg decrease in the population is estimated to reduce stroke mortality by 9% and cardiovascular deaths by 12%.8

Pathophysiology

Hypertension is multifactorial and includes genetic and environmental causes, and the causes of hypertensive crises are poorly understood.9 Hypertension coincides with elevated peripheral vascular resistance (PVR) and normal to low cardiac output.10 The mechanism of the disease is probably an imbalance in autoregulation of the renin-angiotensin system. Malignant-accelerated hypertensive crises are thought to be due to an abrupt increase in PVR caused by humoral vasoconstrictors leading to endothelial injury, vascular permeability, activation of the coagulation cascade, and necrosis of arterioles.11,12 Other hypertensive crises occur when the elevated blood pressure of patients with hypertension exacerbates injury to target organs; it often results in a pathologic feedback loop, which further elevates the blood pressure and exacerbates the damage.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Hypertensive disease occurs in organ systems in which injury to arterioles leads to ischemic damage or hemorrhage. These target organs include the brain, heart, blood vessels, and kidneys (Box 69.1). Therefore, the clinical history and physical examination must include an evaluation of these organ systems.

Differential Diagnosis

Persistently elevated blood pressure can trigger or exacerbate crises in these target organs. Rapid and progressive target organ damage secondary to severely elevated blood pressure defines a hypertensive emergency.13,14 Less commonly, hypertension is the primary crisis. Increasing systemic pressure causes an inflammatory endovasculitis; further damage and aggravation as a result of adrenergic stimulation and vasoconstriction accelerate the elevated blood pressure. The multiorgan disease resulting from an overwhelmed autoregulatory function is called malignant-accelerated hypertension. Inflammatory changes in the cerebral vasculature produce a serious alteration in mental status termed hypertensive encephalopathy. Primary and secondary hypertensive emergencies that must be included in the initial differential diagnosis are listed in Box 69.2.

Accelerated-Malignant Hypertension

Accelerated-malignant hypertension occurs most commonly in young African American males with underlying renal parenchymal disease or renovascular disease. It is most commonly found in patients with long-standing hypertension and usually occurs without encephalopathy.10 When endothelial vasodilator responses are overwhelmed, further hypertension and endothelial damage occur and lead to inflammatory vasculopathy. Marked elevation in blood pressure and characteristic eyeground findings make the diagnosis. Flame-shaped hemorrhages develop around the optic disk because of the high intravascular pressure, and soft exudates are caused by ischemic infarction of the nerve fibers secondary to occlusion of the supplying arterioles. Common symptoms include headache (85%), visual blurring (55%), nocturia (38%), and weakness (30%). Laboratory evidence includes azotemia, proteinuria, hematuria, hypokalemia, and metabolic alkalosis. Papilledema is considered the sine qua non of malignant hypertension. Accelerated hypertension is used to describe the same condition (hemorrhages and exudates) without papilledema. Because the absence of papilledema does not connote a different clinical prognosis or therapy, the term accelerated-malignant hypertension is now recommended.

Hypertension in Pregnancy

Third trimester emergencies are addressed separately in Chapter 121. Emergencies include eclampsia and preeclampsia. Pregnant women between 20 weeks’ gestation and 2 weeks postpartum who have any degree of hypertension (≥140/90 mm Hg) or an increase of more than 30/15 mm Hg above their baseline blood pressure, accompanied by peripheral edema and proteinuria, have preeclampsia. Hypertension is important mainly as a symptom of the underlying disorder rather than as a cause. Preeclampsia is essential to recognize because it can progress suddenly to eclampsia, defined by the occurrence of convulsions. Additional symptoms include headache, visual changes, epigastric pain, oliguria, facial and extremity edema, and HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count). Eclampsia can rapidly progress to coma or death. Magnesium infusion is more effective than other anticonvulsants in this setting. Because definitive treatment consists of delivery of the fetus, the emergency physician (EP) usually collaborates with an obstetrician early in the patient’s course through the department.

Medical Decision Making

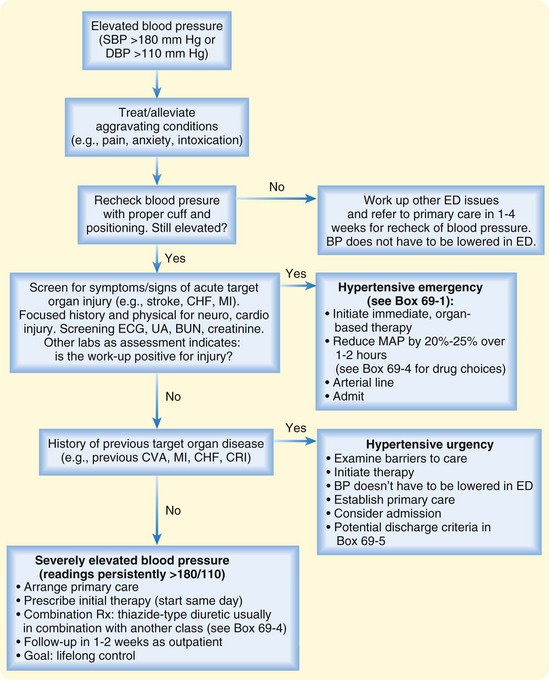

EPs evaluate and treat hypertension in a variety of contexts ranging from compliant patients with well-controlled blood pressure, to asymptomatic patients with increased blood pressure, to critically ill patients with increased blood pressure and acute target organ deterioration. Many patients with severely elevated blood pressure have a combination of long-standing, poorly treated hypertension and acute aggravating conditions such as pain, anxiety, or intoxication. Though a major public health risk, elevated blood pressure is rarely a crisis in the ED. Evidence-based national guidelines exist for the evaluation and treatment of hypertension,15,16 but there is no good evidence to guide the acute treatment of a patient with severely elevated blood pressure. Instead, the EP relies on an understanding of the disease process, its associated complications, and the health care support available to the patient.

Diagnostic Testing

The nature, severity, and management of hypertensive crises are determined by clinical evaluation. When a patient with markedly elevated blood pressure is seen in the ED, accurate measurement of blood pressure is the first step. Blood pressure that is initially elevated in the ED frequently decreases spontaneously by the time that a second reading is obtained.17,18 Any intervention should be based on the composite of several repeated blood pressure measurements. To obtain an accurate measurement, the patient should be seated with the arm at the level of the heart and at least 80% of the arm circumference covered with the cuff bladder. Pressure is evaluated in both arms. Blood pressure measurement with an automated cuff may be inaccurate in patients with atrial fibrillation and other heart rhythm irregularities. Appropriate pain management and relief of the underlying cause (e.g., hypoxia, bladder distention) may resolve the hypertension. Certain medications, over-the-counter preparations, or illicit drugs may transiently exacerbate hypertension (Box 69.3).

The patient’s symptoms direct the EP’s diagnostic evaluation. For example, dyspnea or signs of heart failure are an indication for a chest radiograph, and neurologic findings are an indication for CT of the head. Box 69.1 summarizes some common symptoms and their associated end-organs. Few studies have assessed the prognostic value of laboratory testing in asymptomatic patients with severely elevated blood pressure.19 However, asymptomatic patients with blood pressure persistently higher than 180/110 mm Hg warrant a brief assessment of target organ function (Fig. 69.1). Because renal failure is silent, measurement of serum creatinine or urinalysis (or both) for evidence of renal failure or nephritis is reasonable. An electrocardiogram (ECG) is useful in assessing the baseline level of left ventricular hypertrophy, ischemia, or infarction. The presence of left ventricular hypertrophy on an ECG carries a poor prognosis and necessitates a more vigilant follow-up. When renovascular disease or hypercortisolism is suspected to be a cause of the hypertension, serum should be drawn to determine plasma renin activity and aldosterone levels before administering medications. A urine screen for cocaine and amphetamines may help confirm extrinsic causes of the elevated blood pressure. The value of obtaining a chest radiograph or a complete blood count in patients in the ED without relevant symptoms is likely to be low.

Treatment

Hypertensive Emergency

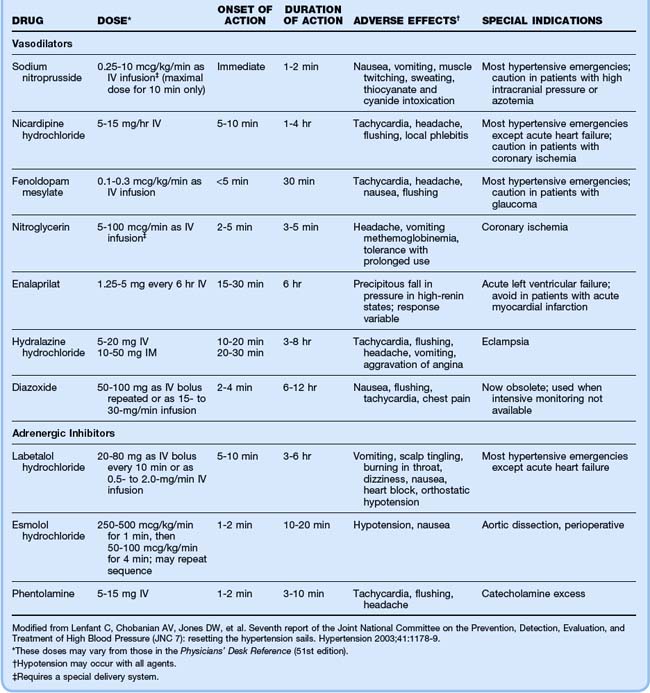

The goal of therapy in patients in hypertensive crisis is a 20% to 25% reduction in MAP over a period of 1 to 2 hours. The ideal drug for treating hypertensive emergencies would easily titrate blood pressure through rapid onset, rapid maximal effect, and rapid offset.5,20–22 These characteristics are found only in parenteral agents. Table 69.1 summarizes the most commonly used medications and doses.

Cerebrovascular Crisis

Blood pressure control should be undertaken with caution in patients with cerebrovascular hypertensive emergencies.23 Parenteral drugs that have a short half-life, are easily titrated, and have minimal effect on the cerebral vasculature are ideal. Because labetalol does not dilate cerebral capacitance vessels, it is theoretically attractive in patients with intracerebral disorders. Caution should be used with direct vasodilators such as nitroprusside in patients with focal brain injury because they can extend an area of ischemia. Although nicardipine is safe and widely used, other calcium channel blockers have been linked to a rise in ICP and are therefore not favored in patients with brain injury.

Treatment of elevated blood pressure in the setting of ischemic CVAs is controversial. When systemic blood pressure is reduced, cerebral autoregulation may fail, thereby extending the ischemic penumbra surrounding the infarct and leading to extension of the stroke. Alternatively, infarction may lead to edema, elevated ICP, and a further reduction in CBF. The current American Stroke Association guidelines recommend lowering blood pressure in patients with stroke only when MAP is greater than 130 mm Hg or systolic blood pressure is greater than 220 mm Hg.23

Theoretically, treatment of elevated blood pressure in patients with hemorrhagic CVAs and subarachnoid hemorrhage should be more aggressive than in patients with ischemic strokes. The rationale is to decrease the risk for ongoing bleeding from ruptured small arteries and arterioles; however, the relationship between rebleeding and systemic blood pressure is unproven.24 As with ischemic CVAs, overly aggressive treatment of hypertension may worsen brain injury by decreasing CPP when ICP is increased. The American Stroke Association guidelines for blood pressure control in patients with hemorrhagic stroke are similar to those for ischemic stroke: blood pressure should be lowered only when MAP is greater than 130 mm Hg or systolic blood pressure is greater than 220 mm Hg. Nimodipine, an oral calcium channel blocker, may be administered to decrease the incidence of vasospasm and rebleeding after subarachnoid hemorrhage, but the drug is not recommended for blood pressure control.

Cardiovascular Crisis

Nitroglycerin (NTG) is favored for the treatment of severe hypertension complicating cardiac ischemia. NTG is a direct vasodilator that affects the venous more than the arterial vasculature. NTG dilates the coronary arteries and, in contrast to nitroprusside, promotes a favorable redistribution of blood flow to ischemic areas. Beta-blockers are also effective and recommended therapy for acute coronary syndromes. The goal of treatment in patients with acute coronary syndromes is reduction of blood pressure to normal if evidence of ischemia persists.25 However, careful blood pressure reduction requires intensive patient monitoring; overly vigorous lowering of blood pressure may worsen the ischemia because coronary perfusion depends on diastolic blood pressure.

Most critical cases of congestive heart failure are treated with a combination of NTG, furosemide, and an ACEI. For patients with pulmonary edema and hypertension, sublingual NTG should be initiated while preparing intravenous NTG. Captopril should be administered orally or sublingually or enalaprilat administered intravenously. If systemic fluid overload is present, intravenous furosemide should be administered. However, up to 25% of patients with heart failure and severely elevated blood pressure may have “dry failure” in which pressure natriuresis makes them fluid depleted. Further diuresis may exacerbate the process and continue to stimulate the renin-angiotensin axis. The decision should be based on clinical judgment of whole-body fluid status. Although beta-blockers have been found to improve survival in patients with chronic congestive heart failure, use in patients with acute pulmonary edema may precipitate immediate worsening because of their negative inotropic effects and bradycardia. Intravenous nesiritide improves hemodynamic function and symptoms in patients with decompensated heart failure and has a modest antihypertensive effect,26 but it has not been well studied in the setting of hypertensive crisis.

With aortic dissection, progression of the vascular injury is dependent not only on the elevated blood pressure but also on the aortic ejection velocity or tachycardia-induced sheer forces. Therefore, a rate-controlling agent such as esmolol should be initiated before starting nitroprusside to avoid the effects of reflex tachycardia.27 Alternatively, labetalol, nicardipine, or fenoldopam has been suggested as possible substitutes for nitroprusside. Labetalol achieves its maximal effect within minutes and then remains effective for several hours, thus allowing titration with small boluses and avoiding the constant monitoring and increased cost required with nitroprusside. Nicardipine and fenoldopam are vasodilators that would require the intensive monitoring needed with nitroprusside but are less toxic alternatives.28

Catecholamine Excess

Patients with severe hypertension secondary to pheochromocytoma are treated with the pure alpha-blocker phentolamine administered intravenously. It may be accompanied by a beta-blocker if needed for tachycardia. Administration of beta-blockers alone in the setting of any sympathomimetic (e.g., cocaine) may leave the alpha receptors “open,” with subsequent worsening of the hypertension.29 Thus, an attractive alternative to beta-blockers is labetalol, a beta-blocker with some alpha-antagonist properties. However, the alpha- and beta-blockade with labetalol may not be equally effective.30 Additionally, benzodiazepines are useful adjuncts in patients with cocaine-induced catecholamine excess. They decrease both the central and peripheral sympathomimetic outflow stimulated by cocaine, thereby lowering the heart rate, psychomotor hyperactivity, and blood pressure.

Next Steps in Care and Admission

Most patients with elevated blood pressure are not in crisis. Very few asymptomatic patients with markedly increased blood pressure will experience a near-term adverse event. Very high blood pressure might be seen in chronically hypertensive patients as a consequence of discontinuing previous therapy or as a result of other easily reversible causes, such as anxiety, pain, drug use, or change in diet.31,32 No evidence has shown that the absolute level of a patient’s blood pressure warrants immediate or aggressive treatment. Rather, in patients with asymptomatic, elevated blood pressure and no evidence of target organ disease, the most important intervention is to ensure proper follow-up. The goal should be lifelong control of the blood pressure.

When the elevated blood pressure may be the artifact of a systemic process such as pain or infection, the best strategy is to refer the patient for reevaluation of the blood pressure once the primary problem has resolved. If the patient has discontinued the blood pressure medications, the regimen should be restarted, barriers to compliance evaluated, and a primary care physician contacted to ensure reevaluation in a week. The hypertension guidelines recommend a thiazide-type diuretic as an initial agent, usually in combination with a drug from another class.15,33 The second agent may be from a number of categories and is best chosen in accordance with any compelling indications in the patient’s history (Box 69.4).

In principle, in individuals without a previous measurement of elevated blood pressure, the blood pressure needs to be rechecked at another visit before the diagnosis of hypertension can be made. However, in individuals with readings persistently higher than 180/110 mm Hg in the ED, the latest national guidelines recommend that combination therapy be started immediately (same day).15 In the best scenario, the EP contacts a primary physician for the patient, who then selects an initial antihypertensive agents or agents and provides follow-up within about a week.

An intermediate group of patients has severely elevated blood pressure and known target organ disease but no active decompensation. An example is a severely hypertensive patient with a previous history of myocardial infarction or stroke. Immediacy arises because a patient with known target organ disease may be considered at higher risk for a hypertension-related adverse event in the short term. However, there is no good evidence base for the best management of these patients. A treatment strategy should be initiated in the ED, although blood pressure does not necessarily need to be lowered during the visit. These patients do require an increased level of vigilance. It may be reasonable to treat them as outpatients, although some may need to be held for short-term observation if their medication compliance or blood pressure monitoring is uncertain; the decision depends on clinical judgment (see Box 69.5).

Tips and Tricks

Elevated triage blood pressure readings often spontaneously improve without treatment. Always recheck abnormal readings.

An initially elevated blood pressure might resolve with proper cuff size or treatment of pain, urinary retention, or hypoxia.

If no emergency is anticipated and immediate parental therapy is not required, patients should be given a dose of the medications that they were supposed to have taken so that some effect has occurred if and when they are ready to be discharged.

Become comfortable with a small number of parental agents; in most instances any one will work.

Elicit a history of use of cocaine or other sympathomimetic drugs.

![]() Patient Teaching

Patient Teaching

Uncontrolled hypertension causes profound and irreversible internal injuries over the long term, many of which are asymptomatic.

Transient blood pressure elevation is rarely dangerous, and management decisions must be based on evidence of extended hypertension.

There are many medications with different convenience and side effect profiles that the primary care provider can substitute to find a good match.

Adherence to a medication regimen is essential for healthy living.

Chest pain, difficulty breathing, severe and new headaches, and focal numbness or weakness are possible signs of heart or brain injury and should be evaluated by a doctor immediately.

![]() Priority Actions

Priority Actions

Severely Elevated Blood Pressure

Recheck the patient’s blood pressure with the correct method in both arms.

Evaluate and treat aggravating conditions (e.g., pain, anxiety, intoxication).

Evaluate for evidence of target organ damage.

Elicit a history of target organ disease.

Administer therapy based on the underlying pathology.

Reevaluate continuously for signs of response to therapy or deterioration.

![]() Documentation

Documentation

Be sure that any elevated blood pressure is noted and addressed.

Be sure to document any change in blood pressure with treatment.

Document possible causes of the elevated blood pressure.

List any past medical history of target organ disease.

List current antihypertensives and any recent changes in medications or noncompliance.

Document the presence or absence of end-organ dysfunction found during assessment of the patient’s elevated blood pressure.

Document patient counseling for medications, reasons to return, and primary care follow-up.

![]() Red Flags

Red Flags

Diagnosing a hypertensive emergency when one does not exist. Patients with hypertensive emergencies have evidence of acute end-organ dysfunction.

Reducing blood pressure too quickly or to too low a level in patients with chronic hypertension whose autoregulation curve has been reset can lead to cerebral or cardiac ischemia.

Lowering a patient’s blood pressure acutely without an urgent indication.

Failing to diagnose hypertension or preeclampsia in pregnant patients with blood pressures higher than 140/90 mm Hg or with an increase in blood pressure of more than 30/15 mm Hg.

Neglecting to match the antihypertensive agent to the clinical scenario.

Chobanian AV, Bakris GI, Black HR, et al. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–2572.

Decker WW, Goodwin SA, Hess EP, et al. Clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult patients with asymptomatic hypertension in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47:237–249.

Gilmore RM, Miller SJ, Stead LG. Severe hypertension in the emergency department patient. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2005;23:1141–1158.

Karras DJ, Ufberg JW, Heilpern KL, et al. Elevated blood pressure in urban emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:835–843.

Varon J. Treatment of acute severe hypertension: current and newer agents. Drugs. 2008;68:283–297.

1 Varon J. Treatment of acute severe hypertension: current and newer agents. Drugs. 2008;68:283–297.

2 Wang TJ, Vasan RS. Epidemiology of uncontrolled hypertension in the United States. Circulation. 2005;112:1651–1662.

3 Cutler JA, Sorlie PD, Wolz M. Trends in hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control rates in United States adults between 1988-1994. Hypertension. 2008;52:818–827.

4 Smith CB, Flower LW, Reinhardt CE. Control of hypertensive emergencies. Postgrad Med. 1991;89:111–116.

5 Zampaglione B, Pascale C, Marchisio M, et al. Hypertensive urgencies and emergencies: prevalence and clinical presentation. Hypertension. 1996;27:144–147.

6 Karras DJ, Ufberg JW, Heilpern KL, et al. Elevated blood pressure in urban emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:835–843.

7 Chiang WK, Jamshahi B. Asymptomatic hypertension in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 1998;16:701–704.

8 Whelton PK, He J, Appel LJ, et al. Primary prevention of hypertension clinical and public health advisory from the National High Blood Pressure Education Program. JAMA. 2002;288:1882–1888.

9 Papadopoulos D, Mourourzis I, Thomopoulos C, et al. Hypertension crisis. Blood Press. 2010;19:328–336.

10 Kaplan NM, Norman M, Lieberman E. Clinical hypertension, 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

11 Ault MH, Ellrodt AG. Pathophysiological events leading to the end-organ effects of acute hypertension. Am J Emerg Med. 1985;3:10–15.

12 Wallach R, Karp RB, Reves JG, et al. Pathogenesis of paroxysmal hypertension developing during and after coronary bypass surgery: a study of hemodynamic and humoral factors. Am J Cardiol. 1980;46:559–565.

13 Shayne PH, Pitts SR. Severely increased blood pressure in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41:513–529.

14 Gilmore RM, Miller SJ, Stead LG. Severe hypertension in the emergency department patient. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2005;23:1141–1158.

15 Chobanian AV, Bakris GI, Black HR, et al. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–2572.

16 Decker WW, Goodwin SA, Hess EP, et al. Clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult patients with asymptomatic hypertension in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47:237–249.

17 Pitts SR, Adams RP. Emergency department hypertension and regression to the mean. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;31:214–218.

18 Dieterle T, Schuurmans MM, Strobel W, et al. Moderate-to-severe blood pressure elevation at ED entry: hypertension or normotension? Am J Emerg Med. 2005;23:474–479.

19 Karras DJ, Kruus KL, Cienki JJ, et al. Evaluation and treatment of patients with severely elevated blood pressure in academic emergency departments: a multicenter study. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47:230–236.

20 Varon J, Marik PE. The diagnosis and management of hypertensive crises. Chest. 2000;118:214–227.

21 Kaplan NM. Management of hypertensive emergencies. Lancet. 1994;344:1335–1338.

22 Grossman E, Ironi AN, Messerli FH. Comparative tolerability profile of hypertensive crisis treatments. Drug Saf. 1998;19:99–122.

23 Adams HP, Adams RJ, Brott T, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with ischemic stroke: a scientific statement from the Stroke Council of the American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2003;34:1056–1083.

24 Broderick JP, Adams HP, Jr., Barsan W, et al. Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: a statement for healthcare professionals from a special writing group of the Stroke Council, American Heart Association. Stroke. 1999;30:905–915.

25 First International Study of Infarct Survival (ISIS-1) Collaborative Group. Randomised trial of intravenous atenolol among 16,027 cases of suspected acute myocardial infarction. ISIS-1. Lancet. 1986;2:57–66.

26 Publication Committee for the VMAC Investigators. Intravenous nesiritide vs nitroglycerin for treatment of decompensated heart failure. Activation of the neurohumoral axis. JAMA. 2002;287:1531–1540.

27 Pretre R, Von Segesser LK. Aortic dissection. Lancet. 1997;349:1461–1464.

28 Iguchi A, Tabayashi K. Outcome of medically treated Stanford type B aortic dissection. Jpn Circ J. 1998;62:102–105.

29 Ramoska E, Sacchetti AD. Propranolol-induced hypertension in treatment of cocaine intoxication. Ann Emerg Med. 1985;14:1112–1113.

30 Boehrer JD, Moliterno DJ, Willard JE, et al. Influence of labetalol on cocaine-induced coronary vasoconstriction in humans. Am J Med. 1993;94:608–610.

31 Viskin S, Berger M, Ish-Shalom M, et al. Intravenous chlorpromazine for the emergency treatment of uncontrolled symptomatic hypertension in the pre-hospital setting: data from 500 consecutive cases. Isr Med Assoc J. 2005;7:812–815.

32 Grossman E, Nadler M, Sharabi Y, et al. Antianxiety treatment in patients with excessive hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2005;18:1174–1177.

33 Psaty BM, Smith NL, Siscovick DS, et al. Health outcomes associated with antihypertensive therapies used as first-line agents. A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 1997;277:739–745.