CHAPTER 64 Human immunodeficiency syndrome

Introduction

Over 50% of all individuals infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are women (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS 2008). Whilst HIV itself has no major specific gynaecological manifestations, it does impinge heavily on gynaecological practice. Some problems, such as recurrent vaginal candidiasis, florid human papilloma virus (HPV) infection and an increased prevalence of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), are the result of increasing immunosuppression. However, many of the current gynaecological issues encountered in the HIV-infected woman, such as contraception, pregnancy and infertility management, are a result of dramatic improvements in available therapy and consequent improvement in overall prognosis.

Background

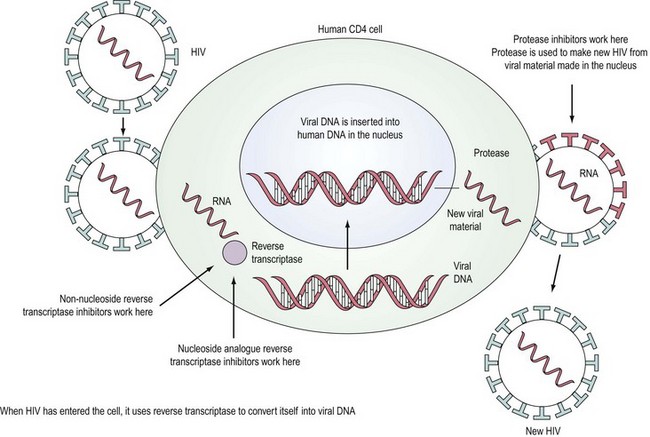

HIV is a retrovirus, a double-stranded RNA virus that uses the enzyme reverse transcriptase to form DNA and integrate itself into the host cell which then becomes a ‘factory’ for producing more virus (Figure 64.1). T-cell helper lymphocytes bearing the CD4 receptor, pivotal in the cell-mediated immune response, are targeted by the virus and destroyed.

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) diagnoses represent a range of disorders including infection and neoplasia (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 1992). The risk of severe immunodeficiency and AIDS increases with the duration of infection. The median time to development of AIDS in untreated HIV-positive patients is approximately 7–10 years. Prior to the development of AIDS, patients may either be asymptomatic or experience persistent generalized lymphadenopathy (enlarged lymph nodes in at least two extrainguinal sites, lasting for at least 3 months and not attributable to any other cause) or symptoms due to immune deterioration that has many manifestations.

Treatment

In the last decade, widespread use of combination antiretroviral therapy in Europe and the USA has substantially reduced the rate of progression to AIDS and improved survival. Deaths that included AIDS-related causes decreased from 3.79/100 person-years in 1996 to 0.32/100 person-years in 2004 (Palella et al 2006). Six classes of antiretroviral agents are now available — nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs), protease inhibitors, integrase inhibitors, entry inhibitors (or fusion inhibitors) and maturation inhibitors — all of which interrupt the virus’ lifecycle (Figure 64.1). The aim of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), a combination of three or more drugs usually including a protease inhibitor or an NNRTI, is to slow progression of the disease by reducing viral load and thus increasing CD4 count. The British HIV Association has published guidelines on when to start HAART (British HIV Association Treatment Guidelines Writing Group 2008). Efavirenz should be considered as the first-line therapy in all patients, unless the patient is trying to conceive and has primary NRTI or NNRTI resistance. After treatment is commenced, viral load should reach ‘undetectable’ levels, usually less than 50 copies/ml. The CD4 count should rise, with levels below 200 × 106/l representing a significant risk of development of an opportunistic infection. Compliance with HAART regimes needs to be in excess of 95% (Paterson et al 2000) for treatment to be effective and to reduce the chance of emergence of resistant virus.

Transmission

HIV has been isolated in blood, seminal fluid, vaginal secretions, cerebrospinal fluid, saliva, lacrimal secretions and breast milk. The concentration in different body fluids varies. The virus may be transmitted by sexual intercourse, intravenous drug use, transfusion, occupational exposure and vertically from mother to child. The predominant route of infection worldwide is heterosexual sex and, with the great majority of the affected population being in their reproductive years, vertical transmission is an increasing problem. Proper use of condoms is known to greatly reduce the risk of transmission (Heikinheimo and Lähteenmäki 2009). Male-to-female transmission is more efficient than female-to-male transmission, with the mucous membrane of the vagina being more permeable and the surface area being greater, although a partner receptive to anal intercourse is at greatest risk. It is difficult to quantify the risk of sexual transmission ‘per act’ as a constellation of factors are involved, although higher levels of viral load and intercurrent sexually transmitted infection (Wasserheit 1992), particularly ulcerative conditions, in either partner make transmission more likely. Use of barrier methods should also be encouraged in concordant HIV-positive couples to reduce the risk of transmission of resistant virus.

Although transmission of HIV between women who have sex with women (Monzon and Capellan 1987) is very rare, cases have occurred. Use of dental dams (latex barriers) should be encouraged to reduce oral contact with vaginal secretions, and shared sex toys should be cleaned appropriately. Salivary hypotonicity is thought to inactivate HIV-infected lymphocytes, and hence salivary transmission is almost certainly very rare. Oral sex, although less risky than vaginal or anal sex, may result in transmission and this may, in part, be the result of the isotonic nature of seminal fluid overcoming the inactivation of infected cells by hypotonic saliva.

HIV testing

There are two methods in routine practice for testing for HIV: screening assay, where blood is sent to the laboratory for testing, or a rapid point of care test (UK National Guidelines for HIV Testing 2008). The recommended first-line assay is one which tests for HIV antibody and p24 antigen simultaneously. These are termed ‘fourth-generation assays’ and have the advantage of reducing the time between the infection and testing HIV positive to 1 month; this is 1–2 weeks earlier than with sensitive third-generation (antibody-only detection) assays. HIV RNA quantitative assays (viral load tests) are not recommended as screening assays because of the possibility of false-positive results, and because they only have a marginal advantage over the fourth-generation assays for the detection of primary infection. Laboratories undertaking screening tests should be able to confirm antibody and antigen/RNA. There is a requirement for three independent assays able to distinguish HIV-1 from HIV-2. These tests could be provided within the primary testing laboratory or by a referral laboratory. All new HIV diagnoses should be made following appropriate confirmatory assays and testing a second sample. Testing including confirmation should follow the standards laid out by the Health Protection Agency (2007).

The HIV epidemic

More than 25 million people have died of AIDS since 1981. Globally, there were an estimated 33 million people living with HIV in 2007. The annual number of new HIV infections declined from 3 million in 2001 to 2.7 million in 2007. Overall, 2 million people died due to AIDS in 2007, compared with an estimate of 1.7 million in 2001. While the percentage of people living with AIDS has stabilized since 2000, the overall number of people living with HIV has increased steadily as new infections occur each year, HIV treatments extend life and new infections still outnumber AIDS deaths. Southern Africa continues to bear a disproportionate share of the global burden of HIV; 35% of HIV infections and 38% of AIDS deaths occurred in that subregion in 2007. Sub-Saharan Africa is home to 67% of people living with HIV (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS 2008).

In 2007, there were an estimated 77,400 persons living with HIV (both diagnosed and undiagnosed), equivalent to 127 persons living with HIV per 100,000 population in the UK (170 per 100,000 men and 84 per 100,000 women). Among 73,300 persons aged 15–59 years living with HIV, 28% are unaware of their infection. A total of 7734 persons (4887 men and 2846 women) were diagnosed with HIV in 2007; a rate of 16 new diagnoses per 100,000 men and nine per 100,000 women. Seventy per cent of the 56,556 persons seen for HIV care were receiving antiretroviral therapy. However, almost one in five HIV-infected persons with severe immunosuppression were not on treatment (Health Protection Agency 2008).

Gynaecological Symptomatology

Menstrual cycle

While, anecdotally, women with HIV are often said to suffer menstrual disturbance, evidence to support an effect of HIV itself on menstrual pattern is sparse and often conflicting. The consensus is that there is no direct effect of HIV on menstrual pattern, although increasingly disturbed cycles may occur in women with advanced HIV infection who are severely immunocompromised (CD4 count <200) (Harlow et al 2000).

HIV shedding into cervical fluid is lowest in the follicular phase and peaks during menstruation (Reicheldorfer et al 2000), with obvious implications for sexual transmission.

Vaginitis

Recurrent vaginal candidiasis is the most common initial clinical manifestation of HIV infection in women (Carpenter et al 1991), and is a problem even at relatively well-maintained CD4 counts. Imam et al (1990) suggested a hierarchy of risk of candidal infection, with recurrent vaginal candidiasis becoming more common with early systemic immunosuppression, oral candidiasis becoming more common with moderate immunosuppression, and oesophageal candidiasis (an AIDS-defining diagnosis) typically occurring with severe immunosuppression. Not only are HIV-infected women more prone to recurrence, but yeasts other than Candida albicans (e.g. Torulopsis glabrata) are isolated more frequently and there is a shorter time before recurrence (Spinollo et al 1994). Response to treatment is usually good, but relapses frequently require retreatment or maintenance therapy.

Pelvic sepsis

Studies of HIV-infected women show no significant difference in the prevalence rates of gonorrhoea and Chlamydia among HIV-positive and HIV-negative women (Minkoff et al 1999). Women with a concurrent sexually transmitted infection are more likely to have a higher viral load in vaginal secretions. Patients should be treated using standard therapy and referred to genitourinary medicine clinics for initiation of contact tracing and follow-up. Pelvic sepsis is probably more common in patients with HIV, but presentation can be varied with less severe symptoms and lesser rises in lymphocyte count, sometimes occurring at the lowest levels of immunocompetence (Korn et al 1993). In general terms, early treatment with standard antibiotics is appropriate and effective.

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

CIN is common in women with HIV (Adachi et al 1993, Massad et al 1999), and prevalence increases with advancing immunosuppression (Schäfer et al 1991, Johnson et al 1992). HIV-positive women are more likely to be infected with HPV (Palefsky et al 1999), and more of this infection is the result of ‘high-risk’ HPV than in the HIV-negative population. Notably, HPV has been found in women who have sex exclusively with women; therefore, even this population must undergo cervical screening.

Data from the pre-HAART era suggested that CIN was more often of higher grade and more often aggressive in women with HIV compared with seronegative women, and that dysplasia was more likely to persist and progress than in seronegative women (Ahdieh et al 1999). Treatment with HAART may influence cervical dysplasia, although results are not consistent across studies, with some suggesting that women treated with HAART experience early regression of lesions (Heard et al 1998) and others showing no convincing evidence of an effect (Moore et al 2002).

Cancer of the cervix

This diagnosis is a gender-specific AIDS diagnosis added to the AIDS definition in 1993. In the UK, there has not been a great rise in the number of cases of cervical carcinoma in HIV-positive women, and this may represent either effective screening or long latency of the disease, with more effective antiretroviral therapy likely to play a role. One study has shown that 2.5% of HIV-positive women aged 15–49 years in European countries have presented with this malignancy as a first AIDS-defining event (Serraino et al 2002).

Pregnancy

In order to prevent vertical transmission, the diagnosis of HIV must be made. The UK’s record on antenatal diagnosis was extremely poor, and the majority of mothers of children vertically infected with HIV only discovered their own diagnosis when the child developed AIDS (Public Health Laboratory Service 1999). The Department of Health subsequently issued guidelines that all pregnant women should be offered an HIV test, with the aim that uptake of the test be 90% by the end of 2002 and the number of vertically HIV-infected babies reduced by 80% (Department of Health 1999). Great progress has already been made towards this goal, with more than 90% of HIV-infected women diagnosed before giving birth in 2007. This high rate of detection in pregnancy means that the estimated proportion of exposed infants who become infected also remained low, at less than 5% (Health Protection Agency 2008).

Antiretroviral therapy

In developed countries, most studies have shown a transmission rate of 15–25% in the absence of treatment, but the use of antiretroviral therapy in pregnancy has reduced transmission rates significantly. Use of AZT (a nucleoside) monotherapy was a breakthrough in reducing vertical transmission (Connor et al 1994). AZT commenced prior to the third trimester, given to the mother intravenously during delivery and given to the neonate orally led to a decrease in transmission by 67% in a placebo-controlled trial. AZT monotherapy does not reduce viral load to undetectable levels, and so does not prevent vertical transmission solely by an effect on viral load. Its precise mechanism of action remains uncertain. For this reason, although AZT monotherapy is still a regime recommended by the British HIV Association, there is a trend towards use of short-term antiretroviral therapy (START) regimes (combination therapy taken from approximately 28 weeks of gestation for the duration of the pregnancy), even in mothers who do not require antiretroviral therapy for themselves (i.e. who have a CD4 count >350). Unlike AZT monotherapy, START regimes aim to reduce viral load to undetectable levels to reduce levels of transmission as much as possible.

The potential for simplified regimes has been assessed, and neviripine (an NNRTI) monotherapy given in two doses, one to the mother during labour and the other to the neonate at 48–72 h, has been shown to be more effective than a single dose of AZT in Africa (Guay et al 1999). However, evidence of subsequent neviripine resistance (which will compromise effective treatment regimes available to the mother) continues to emerge and use of neviripine monotherapy is generally not advised.

Delivery route

In the majority of cases, transmission occurs at the time of delivery; however, this will occur in utero in a small percentage of cases. There is now conclusive evidence to recommend prelabour lower segment caesarean section. A meta-analysis of 15 prospective cohort studies showed a 50% reduction in transmission (International Perinatal HIV Group 1999), and a 70% reduction was found in the European controlled trial (European Mode of Delivery Collaboration 1999). There is uncertainty regarding whether there is a persistent benefit in caesarean section when the mother has an undetectable viral load (<50 copies/ml).

Breast feeding further increases the risk of transmission of HIV by between 7% and 22% (Dunn et al 1992). In the developed world, the majority of postpartum transmission is the result of breast feeding, and its avoidance significantly reduces rates of infection (Kreiss 1997). If a woman decides to breast feed despite this evidence, she should be advised to breast feed exclusively as transmission rates are highest when mixed feeding is employed. There may well be considerable cultural difficulties around not breast feeding, and women need support and advice regarding how to deal with this.

Pregnancy Control

Contraception

Previous advice was for women with HIV to avoid use of intrauterine devices because of potential risks of infection and a possible increase in risk of transmission to male partners resulting from increased duration and heaviness of menses. This has not been substantiated (European Study Group on Heterosexual Transmission of HIV 1992), and this may well be a method of choice in carefully selected candidates (Sinei et al 1998). The progestogen intrauterine system is increasingly used for women with HIV, with the benefits of excellent contraception and a reduction in blood flow.

Planning pregnancy

An HIV-negative woman may have an HIV-positive male partner. HIV does not appear to infect sperm directly. Therefore, if sperm can be isolated from the white blood cells and the seminal plasma in a ‘sperm-washing’ procedure, it should be possible to inseminate a woman safely. Semprini et al (1992), Gilling-Smith (2000) and Marina et al (1998) have experience of more than 3000 cycles of sperm washing and intrauterine insemination or in-vitro fertilization (resulting in 300 live births) with no reported seroconversions. The sperm-washing procedure is expensive and not currently freely available, and some couples may decide to pursue ‘unsafe’ insemination with unprocessed semen or to practice ‘unsafe’ sex. Mandelbrot et al (1997), however, have published results of a study of 92 HIV-negative women whose partners were HIV positive and who had 104 pregnancies. All couples had unprotected intercourse during the fertile period as determined with commercial ovulation predictor kits. There were only four seroconversions, all in couples who did not use condoms consistently during the rest of the cycles.

Infertility

This has been a contentious but important area. Women and their partners should not automatically be denied access to treatment because of HIV infection. As with HIV-negative women with potentially life-shortening conditions such as complicated diabetes, post transplant or a history of cancer, HIV-infected women must be equipped with information and allowed to make their own reproductive decisions (Gilling-Smith et al 2001).

Nosocomial Transmission

Postexposure prophylaxis

Immediately after a percutaneous or mucous membrane exposure to potentially HIV-infected blood, thorough washing with warm running water and soap and clinical evaluation of the injury should be performed. Any bleeding should be encouraged. Consultation with local HIV experts should be as rapid as possible in order that appropriate prophylactic antiretroviral therapy can be commenced, preferably within 1 h, to reduce the risk of seroconversion (Department of Health 2000).

Conclusion

The national strategy for sexual health and HIV (Department of Health 2001) aims to reduce the transmission of HIV, increase the diagnosis of prevalent cases, improve the health and social care of people with HIV, and reduce the stigma attached to the diagnosis. Rates of HIV infection continue to increase, and the number of woman affected is rising. Use of HAART has dramatically improved the prognosis for patients with HIV. Obstetricians and gynaecologists should be aware of the possibility of HIV infection in their patients, and should facilitate HIV testing in order that women are able to experience the benefits of therapy.

KEY POINTS

Adachi A, Fleming I, Burk RD, Ho CYF, Klein RS. Women with human immunodeficiency virus infection and abnormal papanicolaou smears: a prospective study of colposcopy and clinical outcome. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1993;81:372-377.

Ahdieh L, Munoz A, Vlahov D, et al. Cervical neoplasia and repeated positivity of human papillomavirus infection in human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive and -seronegative women. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2000;151(12):1148-1157.

British HIV Association Treatment Guidelines Writing Group. British HIV Association guidelines for treatment of HIV-1-infected adults with anti-retroviral therapy 2008. HIV Medicine. 2008;9:563-608.

Carpenter CC, Mayer KH, Stein MD, Leibman BD, Fisher A, Fiore TC. Human immunodeficiency virus infection in North American women: experience with 200 cases and a review of the literature. Medicine. 1991;70:307-325.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 1992;41:1-19.

Connor EM, Sperling RS, Gelber R, et al. Reduction of maternal–infant transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 with zidovudine treatment. New England Journal of Medicine. 1994;331:1173-1180.

Department of Health. Targets Aimed at Reducing the Numbers of Children Born with HIV. London: DOH; 1999.

Department of Health. HIV Post-exposure Prophylaxis: Guidance from the UK Chief Medical Officer’s Expert Advisory Groups on AIDS. London: DOH; 2000.

Department of Health. The National Strategy for Sexual Health and HIV. London: DOH; 2001.

Dunn DT, Newell ML, Ades AE, Peckham C. Estimates of the risk of HIV-1 transmission through breast feeding. The Lancet. 1992;320:585-588.

European Mode of Delivery Collaboration. Elective caesarean section versus vaginal delivery in prevention of vertical HIV-1 transmission: a randomised clinical trial. The Lancet. 1999;353:1035-1039.

European Study Group on Heterosexual Transmission of HIV. Comparison of female to male and male to female transmission of HIV in 563 stable couples. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 1992;304:809-813.

Gilling-Smith C. Assisted reproduction in HIV discordant couples. AIDS Reader. 2000;10:581-587.

Gilling-Smith C, Smith JR, Semprini AE. HIV and infertility: time to treat. There’s no justification for denying treatment to parents who are HIV positive. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 2001;322:566-567.

Guay LA, Musoke P, Fleming T, et al. Intrapartum and neonatal single-dose neviripine compared with zidovudine for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 in Kampala, Uganda: HIVNET 012 randomised trial. The Lancet. 1999;354:795-802.

Harlow SD, Schuman P, Cohen M, et al. Effect of HIV infection on menstrual cycle length. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2000;24:68-75.

Health Protection Agency. Anti-HIV Screening — Minimum Testing Algorithm. National Standard Method VSOP. 11(1), 2007. HPA, London. Available at: http://www.hpa-standardmethods.org.uk/documents/vsop/pdf/vsop11.pdf

Health Protection Agency. HIV in the United Kingdom 2008 Report. HPA, London. Available at http://www.hpa.org.uk/webc/HPAwebFile/HPAweb_C/1227515298354, 2008.

Heard I, Schmitz V, Costagliola D, Orth G, Kazatchkine MD. Early regression of cervical lesions in HIV-seropositive women receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 1998;12:1459-1464.

Heikinheimo O, Lähteenmäki P. Contraception and HIV infection in women. Human Reproduction Update. 2009;15:165-176.

Imam N, Carpenter CC, Mayer KH, Fisher A, Stein M, Danforth SB. Hierarchical pattern of mucosal Candida infections in HIV-seropositive women. American Journal of Medicine. 1990;89:142-146.

International Perinatal HIV Group. Mode of delivery and vertical transmission of HIV-1: a meta-analysis from 15 prospective cohort studies. New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;340:977-987.

Johnson JC, Burnett AF, Willet GD, Young MA, Doniger J. High frequency of latent and clinical human papillomavirus cervical infections in immunocompromised human immunodeficiency virus infected women. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1992;79:321.

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Report on the Global HIV/AIDS Epidemic. UNAIDS, Geneva. Available at http://www.unaids.org/en/KnowledgeCentre/HIVData/GlobalReport/2008/2008_Global_report.asp, 2008.

Korn AP, Landers DV, Green JR, Sweet RL. Pelvic inflammatory disease in human immunodeficiency virus-infected women. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1993;82:765-768.

Kreiss J. Breast feeding and vertical transmission of HIV-1. Acta Paediatrica. 1997;421(Suppl):113-117.

Mandelbrot L, Heard I, Henrion-Geant E, Henrion R. Natural conception in HIV-negative women with HIV-infected partners. The Lancet. 1997;349:850-851.

Marina S, Marina F, Alcolea R, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type-1 serodiscordant couples can bear healthy children after undergoing intrauterine insemination. Fertility and Sterility. 1998;70:35-39.

Massad LS, Riester KA, Anastos KM, et al. Prevalence and predictors of squamous cell abnormalities in Papanicolaou smears from women with HIV-1. Women’s Interagency HIV Study Group. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 1999;21(1):33-41.

Minkoff HL, Eisenberger-Matityahu D, Feldman J, Burk R, Clarke L. Prevalence and incidence of gynaecologic disorders among women infected with human immunodeficiency virus. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1999;180:824-836.

Monzon OT, Capellan JMB. Female-to-female transmission of HIV. The Lancet. 1987;2:40-41.

Moore AL, Sabin CA, Madge S, Mocroft A, Reid W, Johnson MA. Highly active antiretroviral therapy and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. AIDS. 2002;16:927-929.

Palefsky JM, Minkoff H, Kalish LA, et al. Cervicovaginal human papillomavirus infection in human immunodeficiency virus-1 positive and high risk HIV-negative women. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1999;91:226-236.

Palella FJJr, Baker RK, Moorman AC, et al. Mortality in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era: changing causes of death and disease in the HIV outpatient study. HIV Outpatient Study Investigators. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2006;43:27-34.

Paterson DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, et al. Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2000;133:21-30.

Public Health Laboratory Service. Available at http://www.phls.co.uk/facts/HIV/hiv.htm, 1999.

Reicheldorfer BA, Coombs R, Wright KD, et al. Effect of menstrual cycle on HIV-1 levels in the peripheral blood and genital tract. WHS 001 Study team. AIDS. 2000;14:2101-2107.

Schäfer A, Friedmann W, Mielke M, Schwartländer B, Koch MA. The increased frequency of cervical dysplasia-neoplasia in women infected with human immunodeficiency virus is related to the degree of immunosuppression. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1991;164:593-599.

Semprini AE, Levi-Setti P, Bozzo M, et al. Insemination of HIV-negative women with processed semen of HIV-positive partners. The Lancet. 1992;340:1317-1319.

Serraino D, Dal Maso L, La Vecchia C, Franceschi S. Invasive cervical cancer as an AIDS-defining illness in Europe. AIDS. 2002;16:781-786.

Sinei SK, Morrison CS, Sekadde-Kigondu C, Allen M, Kokonya D. Complications of use of intrauterine devices among HIV-1 infected women. The Lancet. 1998;351:1238-1241.

Spinollo A, Michelone G, Cavanna C, et al. Clinical and microbiological characterisation of symptomatic vulvovaginal candidiasis in HIV-seropositive women. Genitourinary Medicine. 1994;70:268-272.

UK National Guidelines for HIV testing. Joint BHIVA, BASHH and BIS Guidelines [Writing Committee (Palfreeman A, Fisher M, Ong E et al)], BHIVA, London, UK]. Available at http://www.bhiva.org/files/file1031097.pdf, 2008.

Wasserheit JN. Epidemiological synergy. Interrelationships between human immunodeficiency virus infection and other sexually transmitted diseases. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 1992;19:61-77.

Williams AB, Darragh TM, Vranizan K, Ochia C, Moss AR, Palefsky JM. Anal and cervical human papillomavirus infection and risk of anal and cervical epithelial abnormalities in human immunodeficiency virus-infected women. Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1994;83:205-211.