67

Human Herpesviruses

General

Herpes Simplex Viruses (HSV-1/HHV-1 and HSV-2/HHV-2)

• Ubiquitous pathogens that produce primarily orolabial (HSV-1 > HSV-2) and genital infections (HSV-2 > HSV-1) characterized by recurrent vesicular eruptions (Table 67.1).

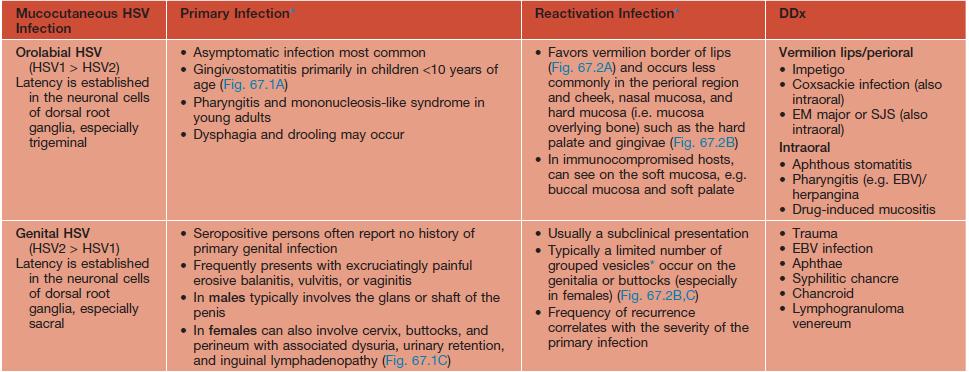

Table 67.1

Major clinical features of classic herpes simplex virus (HSV) orolabial and genital infections.

~90% of U.S. adults are seropositive for HSV-1 and ~25–30% are seropositive for HSV-2, with an increasing seroprevalence for the latter. Treatment is outlined in Table 67.3.

* For the description of typical lesions, see text; occasionally, intact vesicles are not seen but rather grouped ulcerations with hemorrhagic crusts predominate.

EM, erythema multiforme; SJS, Stevens–Johnson syndrome; DFA, direct fluorescent antibody; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.

• Transmission can occur during both symptomatic and asymptomatic periods of viral shedding.

• A wide range of clinical presentations exist, with asymptomatic infection being the most common.

– Onset is usually 3–7 days after exposure.

– Initial lesions: small round vesicles on an erythematous base; often painful or burning; the grouping of these vesicles is a clue to the diagnosis; vesicles may become umbilicated or pustular, followed by erosions or ulcerations with hemorrhagic crusts, often with a scalloped border; lesions resolve over 2–6 weeks (Fig. 67.1).

Fig. 67.1 Primary herpes simplex virus (HSV) infections. A Primary herpes gingivostomatitis due to HSV-1 in a child. Note the coalescing lesions with scalloped borders. B HSV-2 infection in a teenager (primary vs. non-primary initial infection). Note the scalloped borders. C Primary genital HSV infection. In addition to 1- to 2-mm hemorrhagic crusts, there are perifollicular vesicopustules. A, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD; B, Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD; C, Courtesy, Stephen K. Tyring, MD.

– Localized prodrome of dysesthesia (e.g. burning/tingling, pain, pruritus) and tenderness.

– Mucocutaneous lesions similar as in primary but fewer in number, less severe, and shorter duration (Fig. 67.2).

Fig. 67.2 Reactivation of herpes simplex virus (HSV) infections. A Recurrent HSV-1 infection on the cheek. Occasionally such lesions are misdiagnosed as cellulitis or bullous impetigo. B Intact grouped vesicles on the penis. Note the genital wart at the base of the penis. C Grouped vesiculopustules on the buttock, a common location in women. D Healing ulcerations with scalloped borders on the penis. A, Courtesy, Kalman Watsky, MD; B, C, Courtesy, Louis A. Fragola, Jr., MD; D, Courtesy, Joseph L. Jorizzo, MD.

• In addition to the classic orolabial and genital infections, HSV can cause other infections (Table 67.2; Figs. 67.3–67.7).

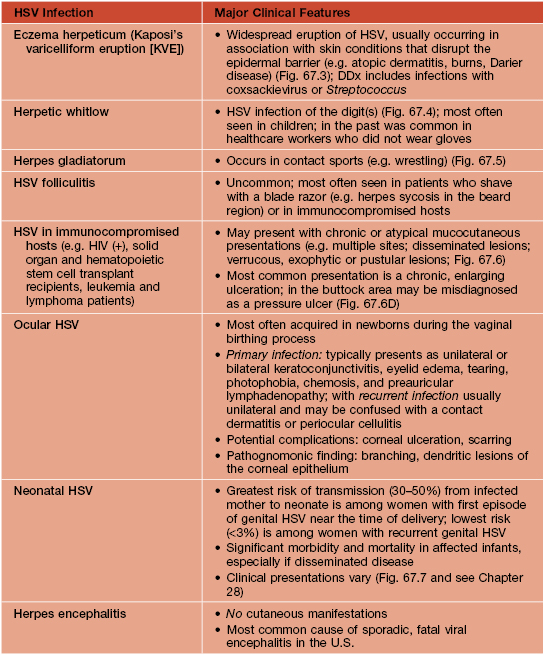

Table 67.2

Major clinical features of other herpes simplex virus (HSV) infections.

Treatment is outlined in Table 67.3.

Fig. 67.3 Eczema herpeticum. Monomorphic, punched-out erosions with a scalloped border in this infant with a history of facial atopic dermatitis. Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

Fig. 67.4 Herpetic whitlow. On the finger of a child (A) and on the finger in an adult (B). Herpetic whitlow is sometimes misdiagnosed as cellulitis or blistering dactylitis, or, depending on the distribution, paronychia. B, Courtesy, Eugene Mirrer, MD.

Fig. 67.5 Herpes gladiatorum. Grouped vesicles and erosions on the neck of a high school wrestler. Courtesy, Louis A. Fragola, Jr., MD.

Fig. 67.6 Herpes simplex viral infections in immunocompromised hosts. A Enlarging ulcerations in a child with acute lymphocytic leukemia who was presumed to have a Rhizopus infection, and (B) in a young man with AIDS. C Coalescence of eroded, yellow-white papules and plaques on the tongue. D Chronic perianal ulcerations in an HIV-infected male. D, From Callen JP, Jorizzo JL, et al. Dermatological Signs of Internal Disease, 4th edn.; Saunders/Elsevier, 2009.

Fig. 67.7 Neonatal herpes. Grouped papulovesicles with an erythematous base on the chest. Note the scalloped borders in areas of coalescence. Courtesy, Frank Samarin, MD.

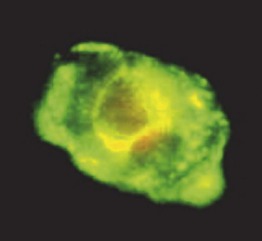

• DDx and Dx: see Table 67.1 and Fig. 67.8.

Fig. 67.8 Direct fluorescent antibody assay. A keratinocyte that is infected with herpes simplex virus fluoresces green. This assay can also detect the presence of varicella–zoster virus and it has a rapid turnaround time. Courtesy, Marie L. Landry, MD.

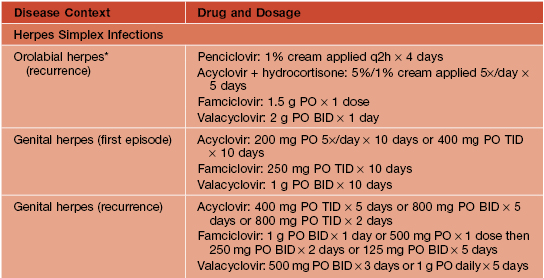

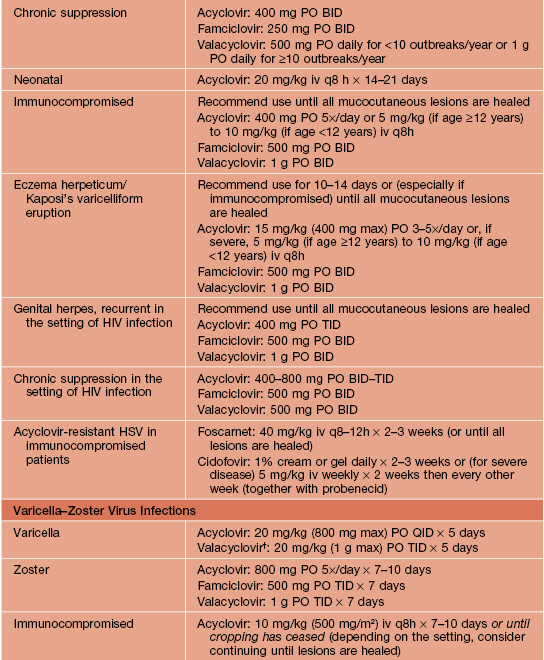

Table 67.3

Antiviral therapy for herpes simplex virus and varicella–zoster virus infections.

* Indications for and efficacy of antiviral treatment for initial episodes of orolabial herpes in immunocompetent adults have not been defined, but the regimens used for initial genital episodes can be considered in individuals with severe disease; acyclovir 15 mg/kg (200 mg max) PO 5×/day × 7 days (initiated within 3 days of disease onset) has been shown to be beneficial in young children with primary herpes gingivostomatitis.

† FDA-approved for ages 2–17 years; pharmacies can compound valacyclovir tablets into an oral suspension (25 or 50 mg/ml).

BID, twice daily; iv, intravenously; PO, orally; q2h, every 2 hours; daily, once a day; qid, four times a day; TID, three times a day.

Varicella–Zoster Virus (VZV or HHV-3)

• Primary varicella infection (chickenpox).

– Usually self-limited in otherwise healthy children but more severe with more numerous lesions and a greater risk for complications in adults (including pregnant women) and immunocompromised individuals (Table 67.4; Fig. 67.9).

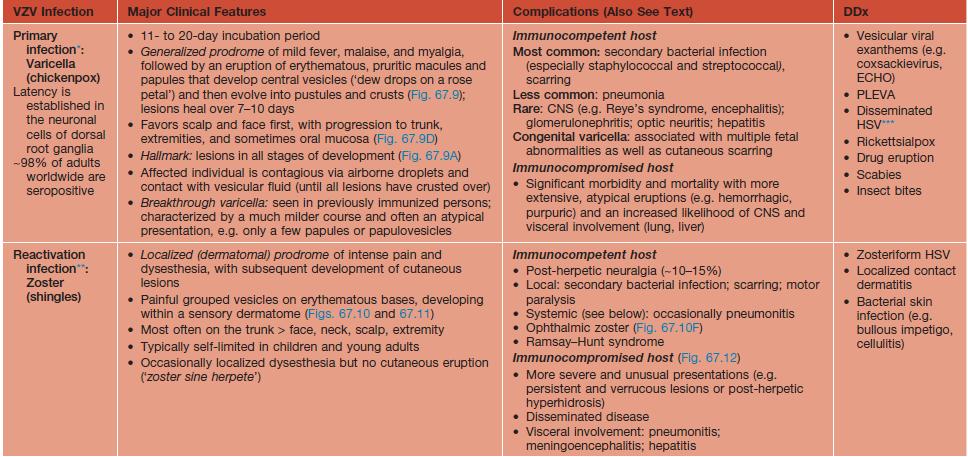

Table 67.4

Major clinical features of varicella–zoster virus (VZV) infections.

Treatment is outlined in Table 67.3.

* Prevention is now a major focus: In the United States, all eligible children are recommended to receive the two-dose, live-attenuated VZV vaccine. Varicella IgG (VIG) given to immunocompromised hosts with first-time exposure; VIG given to neonates whose mothers became infected shortly before birth.

** Prevention is now a major focus in the United States and United Kingdom; The FDA has approved a one-time live-attenuated VZV vaccine for eligible persons older than 50 years (efficacy is ~50%).

*** Especially in immunocompromised hosts.

HSV, herpes simplex virus; ECHO, enteric cytopathic human orphan; PLEVA, pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta; DFA, direct fluorescent antibody; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.

Fig. 67.9 Primary varicella–zoster virus (VZV) infection (varicella or chickenpox). Widespread lesions in different stages of evolution (A). Vesicles often develop central umbilication (B) and some lesions become pustular (C). Note the dermatographism related to scratching (C). Oral lesions can also occur (D). A, B, Courtesy, Robert Hartman, MD; C, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD; D, Courtesy, Judit Stenn, MD.

• Herpes zoster (shingles) – reactivation of VZV.

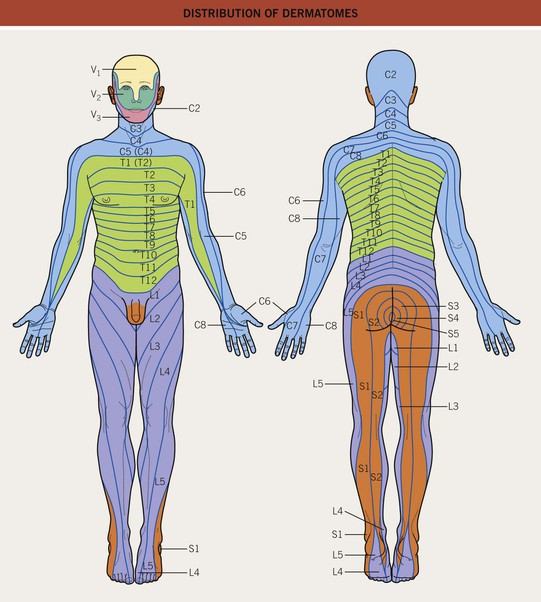

– Reactivation results in a sensory neuritis and painful neuralgia, followed by a dermatomal vesicular eruption; clinical course is outlined in Table 67.4 (Figs. 67.10–67.12).

Fig. 67.11 Distribution of dermatomes.

Fig. 67.10 Herpes zoster (shingles) infection. A–C Erythematous, edematous plaques with early vesicle formation. Note the perifollicular accentuation (B). D and E Later stages of evolution with prominent pustule formation (D) and a dusky purple color associated with older vesicles (E). F Ophthalmic zoster (V1) with sharp midline demarcation of erythema and crusts on the forehead as well as contralateral periorbital edema. G Bullous variant on the flexor arm. B, Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD; D, Courtesy, Louis A. Fragola, Jr., MD.

Fig. 67.12 Herpes zoster (shingles) in immunocompromised hosts. A Chronic verrucous zoster in an HIV-infected patient. B Disseminated cutaneous zoster with multiple violet-black papules on the feet. Patients with disseminated cutaneous skin lesions should be evaluated for possible CNS or visceral involvement, e.g. hepatic, pulmonary, especially if they are immunocompromised.

– Rx: early antiviral treatment (within 72 hours of the onset of the first vesicle) is ideal, but initiation after 72 hours but within 7 days may also be helpful (see Table 67.3).

– Selected complications of herpes zoster:

• Defined as >20 vesicles outside the area of the primary or adjacent dermatomes.

• Implies viremia and an increased risk for visceral or CNS involvement (see Table 67.4).

• Requires intravenous acyclovir.

2. Post-herpetic neuralgia (PHN) and post-herpetic itch (PHI).

• Affects 10–15% of patients; incidence and severity increase with age.

• Note that opioids are typically ineffective or even aggravating in patients with PHI.

3. Ocular involvement (see Fig. 67.10F).

• Occurs in ~10% of patients, with 20–70% developing ocular disease (occasionally blindness).

• Due to VZV reactivation in the first division of the trigeminal nerve (V1).

• Clues to its diagnosis include lesions in the V1 distribution (see Fig. 67.11), which may be accompanied by unilateral eye pain or conjunctivitis.

• Initial and longitudinal evaluation by ophthalmology is required.

4. Ramsay–Hunt syndrome (herpes zoster oticus).

• Due to VZV reactivation in the geniculate ganglion.

• Clues to its diagnosis: vesicles in the ear canal, tongue, and/or hard palate.

• If the vestibulocochlear nerve is also affected, may have tinnitus, hearing loss, or vertigo.

Epstein–Barr Virus (EBV or HHV-4)

• Table 67.5 and Figs. 67.13 and 67.14.

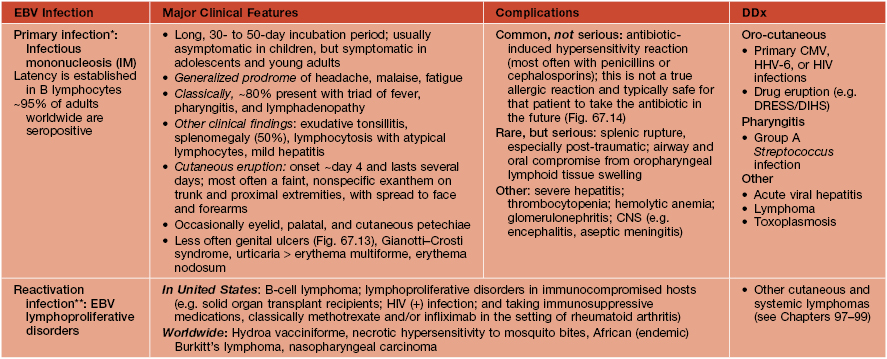

Table 67.5

Major clinical features of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infections.

Treatment of primary EBV infection is primarily supportive; treatment of EBV lymphoproliferative disorders is focused on reversing the host’s immunosuppressed state, if possible.

* Diagnosis of suspected primary EBV infection is confirmed by a positive heterophile antibody test (‘Monospot’ test); if the heterophile antibody test is negative but IM is still suspected (e.g. early in the course of disease [≤6 weeks]) or in younger children (<2-years), then consider: repeat heterophile antibody testing, EBV-specific serologies, and/or EBV DNA levels.

** Diagnosis of a suspected EBV lymphoproliferative disorder is confirmed by the presence of elevated circulating EBV DNA levels.

DRESS, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (also known as DIHS, drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome); CMV, cytomegalovirus.

Fig. 67.13 Genital ulcers associated with primary EBV infection. Extreme pain with urination required placement of a Foley catheter in this 13-year-old girl. EBV-related genital ulcers are often misdiagnosed as a genital herpes simplex virus infection. Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

Cytomegalovirus (CMV or HHV-5)

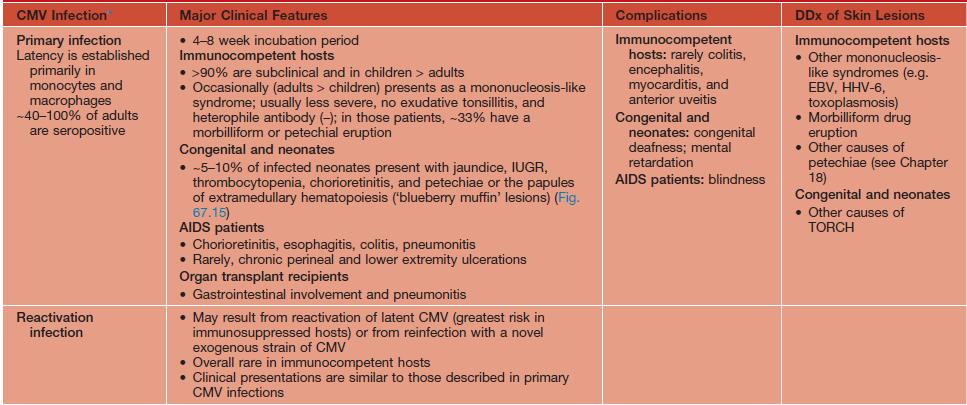

• Table 67.6 and Fig. 67.15.

Table 67.6

Major clinical features of cytomegalovirus (CMV) infections.

Treatment of uncomplicated CMV infection in immunocompetent hosts is primarily supportive; treatment in immunocompromised hosts or in those with complicated infections involves systemic therapy (e.g. intravenous ganciclovir, oral valganciclovir, cidofovir, foscarnet). Prevention is possible by matching CMV serologies between donor and transplant recipients.

* Diagnosis is made via various techniques: (1) serologies (e.g. IgM and IgG antibodies); (2) various molecular amplification techniques (e.g. PCR); (3) cultures (helpful to determine if drug resistance is present); (4) CMV antigenemia assays (helpful in immunosuppressed hosts); (5) biopsy of cutaneous lesions (e.g. ulcerations) may show characteristic findings of enlarged endothelial cells with prominent intranuclear inclusions (‘owl’s eyes’)

EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; IUGR, intrauterine growth retardation; TORCH, toxoplasmosis, other agents, rubella, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus.

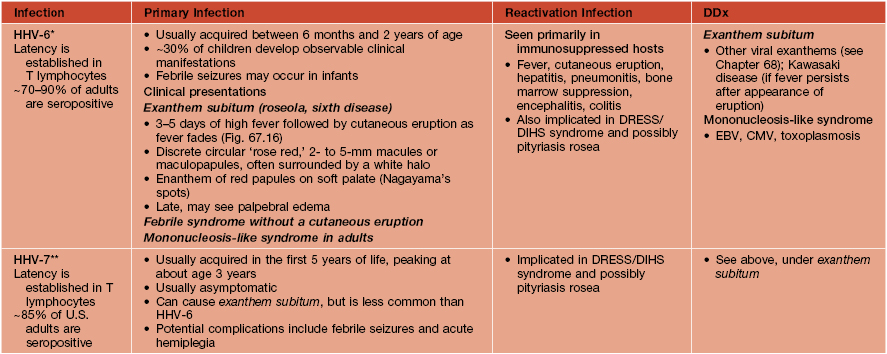

Human Herpesvirus 6 and 7 (HHV-6 and HHV-7)

• Table 67.7 and Fig. 67.16.

Table 67.7

Major clinical features of human herpesvirus 6 and 7 (HHV-6 and HHV-7) infections.

No definitive treatment is available.

* Diagnosis of HHV-6 is clinical in most cases of classic exanthema subitum in children; laboratory investigation with serologies and seroconversion data (e.g. IgM and IgG antibodies and titers) or detection of HHV-6 DNA in clinical/tissue specimens is reserved for atypical presentations and complications or in immunosuppressed hosts.

** Serologic tests and quantitative PCR may be useful for immunosuppressed hosts.

DRESS, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (also known as DIHS, drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome); EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; CMV, cytomegalovirus.

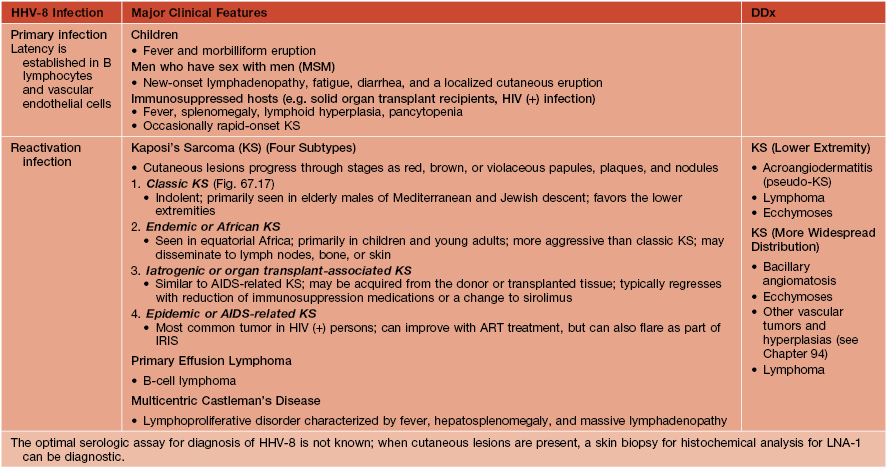

Human Herpesvirus 8 (Kaposi’s Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus [KSHV])

• Table 67.8 and Fig. 67.17.

Table 67.8

Major clinical features of human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) infections.

HHV-8 is also known as Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS)-associated herpesvirus. Treatment of KS involves reconstitution of the host’s immune system (e.g. decrease immunosuppressive therapy, ART, change to sirolimus); systemic and intralesional chemotherapy; radiation therapy; cryotherapy.

ART, antiretroviral therapy; IRIS, immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome.

For further information see Ch. 80. From Dermatology, Third Edition.