CHAPTER 26 Hirsutism and virilization

Introduction

Hair follicles are stimulated by androgens to either enlarge on the face and body or to shrink on the vertex of the scalp. These changes occur in the female after puberty and probably develop to a small extent in all women. A small number of women develop excessive changes in hair, prompting advice from beauty therapists or physicians. The heaviness of facial or body hair growth that is necessary for a woman to consider herself to be hirsute is dependent on racial, cultural, social and economic factors. Although the pattern of hair growth is similar in all races, there is a variation in the heaviness of growth between ethnic groups. Furthermore, Shah (1957) in India and Lunde and Grottum (1984) in Norway have both stressed that women are more likely to consider themselves to be hirsute if they have significant growth on the upper lip, chin, chest and upper back.

The problem with defining hirsutism is that all measurements are subjective (Barth 1997). Large studies of unselected women in the USA (DeUgarte et al 2006) and Scandinavia (Lunde and Grottum 1984) have shown that it is impossible to separate hirsute from non-hirsute women on the basis of hair scoring scales, as women with similar hair scores may or may not consider that they have excessive hair growth. The problem with physician scales is that they do not consider the effect of hair localization. Is a women with facial hair but no body and limb hair more or less hirsute than a woman with a hairless face but a hairy trunk and limbs?

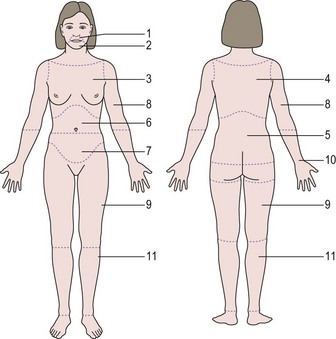

The standard scoring scale designed by Ferriman and Gallwey (1961) (Figure 26.1) defined 1.2% of females as hirsute, but this was based purely on mathematical grounds (i.e. 2 standard deviations from the mean). This contrasts with women’s perspectives. A study of 400 unselected students, 60% of whom were Welsh, showed that 9% considered themselves to be disfigured by their facial hair growth (McKnight 1964). A study of unselected women in the USA found that approximately 20% of women had modified Ferriman and Gallwey scores greater than 3, and of these women, 70% considered themselves to have excessive facial and body hair. Furthermore, women with hirsutism give their hair growth a higher score than their physicians (Kozloviene et al 2005).

Hirsuties or hypertrichosis?

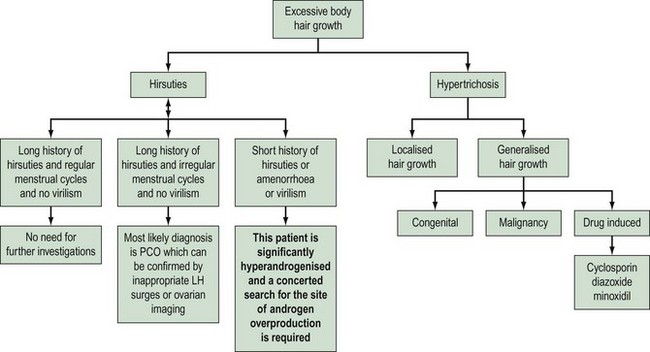

Hypertrichosis needs to be differentiated as it is not androgen mediated and therefore does not respond to antiandrogen therapy. The onset of hair growth is not related to puberty; there is no hair growth pattern but there is a uniform diffuse growth of hair over the body. The individual hair shafts tend to be finer and lie flat against the skin, rather than being coarse, curly and rising above the skin surface. Hypertrichosis may be congenital or acquired due to drug therapy and some metabolic disorders (Table 26.1).

| Causes of hirsutism | Causes of hypertrichosis |

|---|---|

PCO, polycystic ovaries.

Investigation

Diagnostic approach to the hirsute woman

What is the evidence for this approach?

Moran et al (1994) reported on 250 premenopausal (<38 years) women presenting with various symptoms who were noted to be hirsute. Ninety-six percent were diagnosed with polycystic ovaries, idiopathic hirsuties or obesity; 2% were diagnosed with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH); and 1.6% were either iatrogenic (one case) or due to an ovarian tumour (two cases) or Cushing’s syndrome (one case).

O’Driscoll et al (1994) reported a series of 350 consecutive patients who had presented with either hirsuties or androgenic alopecia. They identified eight women from this series with clear endocrine diseases; two had pituitary tumours (prolactinoma and acromegaly). The others were identified by a grossly elevated serum testosterone (>5 nmol/l). In total, 13 women had elevated testosterone; six had polycystic ovaries, two had late-onset CAH, one had virilizing CAH that had been ignored in childhood, one had an adrenal carcinoma, one had a postmenopausal Leydig cell tumour, one had corticosteroid 11-reductase deficiency, and the diagnosis in one hyperandrogenized postmenopausal woman was not elucidated. On the basis of the clinical details given in the report, only two diagnoses of late-onset CAH would have been missed by clinical evaluation alone (one had regular cycles and two children, the other had a long history of oligomenorrhoea; both had polycystic ovaries on ultrasound examination).

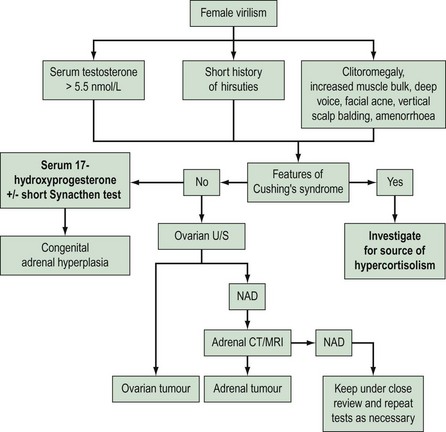

Arguably, the most important purpose for investigation is to identify those women with androgen-secreting tumours, since they require different therapy. Derksen et al (1994) reported a series of two adrenal adenomas and 12 carcinomas in which hirsutism was the presenting symptom. The women with adenomas were described as being severely virilized. Six of the women with carcinoma had clinical signs of Cushing’s syndrome; of the remaining six cases, four were severely virilized and the other two women presented with abdominal pain.

Functioning ovarian tumours which secrete androgens and therefore cause virilization are rare and represent only 1% of all ovarian tumours. In these cases, hirsuties is a nearly universal feature. Amenorrhoea develops rapidly in all premenopausal patients, and systemic virilization with alopecia, cliteromegaly, deepening of the voice and a male habitus develops in approximately half of patients. Meldrum and Abraham (1979) reviewed the literature of 43 women with virilizing ovarian tumours; seven had a serum testosterone level below 7.0 nmol/l but all were clinically virilized, and one 65-year-old woman was reported as not virilized but her serum testosterone level was more than 12 nmol/l.

In conclusion, the vast majority of hirsute women have polycystic ovaries, and those women with androgen-secreting tumours can be identified by clinical evaluation and a single serum testosterone estimation (Figure 26.3).

How Useful Are Endocrine Tests?

The laboratory findings in reports of hirsute women demonstrate considerable heterogeneity. This may be due to differences in diagnostic criteria for the studies; for example, hyperandrogenaemia, acne and/or hirsutism, or women with polycystic ovaries/menstrual disturbances. A further factor may be the degree of hair growth necessary to define whether a woman is considered to be hirsute (Barth et al 2007). A third point has been proposed by Toscano et al (1983) who suggested that the endocrine abnormalities are dependent on the length of the history of hirsutism. They posed the question ‘is hirsutism an evolving syndrome?’, and whilst their interpretation of the findings may be argued, it is clear that (i) a degree of hirsutism and/or oligomenorrhoea is necessary before hormonal abnormalities may be present, and (ii) not all hirsute women have abnormal circulating hormones.

Investigations to diagnose polycystic ovaries

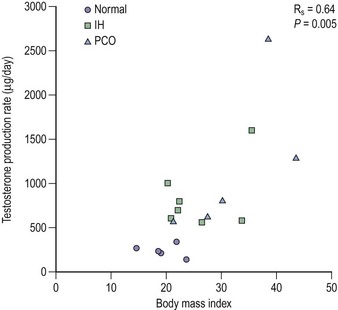

Ovarian imaging compares extremely favourably with anatomical appearance in those subjects who have had abdominal laparoscopy, whereas the use of gonadotrophins is less well established as a diagnostic tool. Approximately 50% of women with polycystic ovaries have an elevated concentration of luteinizing hormone (LH), and 40% of women with elevated LH have polycystic ovaries. The use of gonadotrophins is further complicated by assay methodology. In view of these factors, the latest guidelines to diagnose polycystic ovaries have abandoned their use (Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group 2004). The over-riding problem is that approximately 10% of women with ultrasound-diagnosed polycystic ovaries will have normal endocrine tests, however many are performed. This may be due to the relationship between body weight and the dynamics of testosterone production (Figure 26.4).

Figure 26.4 Although serum testosterone is usually reported as slightly elevated in women with polycystic ovaries (PCO) or hirsuties, it can be seen from this redrawing of the original data of Bardin and Lipsett (1967) that testosterone production rates are closely related to body mass irrespective of the patient’s phenotype. IH, idiopathic hirsuties.

Data redrawn from Thomas PK, Ferriman DG. Variation in facial and pubic hair growth in white women. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1957 Jun;15(2):171–180, Wiley.

Most recommendations suggest a battery of androgen tests, but this is probably still based on the unreliability of testosterone assays (Rosner et al 2007). This should become less of a problem as measurement by tandem mass spectrometry becomes more routine. A single testosterone measurement taken in the morning during the early follicular phase measured with a reliable assay is probably all that is required in the first instance (Martin et al 2008).

Short Synacthen test for late-onset congenital adrenal hyperplasia

The incidence of late-onset CAH in women with hirsutism is variously reported at 1–12% depending on the source of patient referral. Short Synacthen testing has been used extensively as a research tool, but its use in routine practice cannot be recommended. Firstly, there is no sharp cut-off value of 17-hydroxyprogesterone following Synacthen that can be used to define late-onset CAH. Secondly, treatment for hirsute women with late-onset CAH should not be influenced by the diagnosis since antiandrogen therapy with cyproterone acetate (CPA) is more effective than corticosteroids (Spritzer et al 1990). Moreover, corticosteroids aggravate insulin resistance and, theoretically, worsen the hyperandrogenism. Finally, there does not appear to be a need to identify women with late-onset CAH since they do not seem to need protection against stress-related corticosteroid deficiency.

Evaluation of metabolic factors

Polycystic ovary syndrome is now recognized to be a systemic disorder underpinned by insulin resistance. Insulin plays a key role as an amplifier of gonadotrophin-stimulated ovarian androgen production, and also as a growth factor for hair follicle. The effects of hyperinsulinaemia include android obesity, glucose intolerance, hyperlipidaemia and possibly impaired fibrinolysis. The lipid profiles show the pattern associated with patients who have ischaemic heart disease, namely raised triglycerides and low high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol, and hirsute women undergoing coronary angiography have more pronounced arterial disease than non-hirsute women (Wild et al 1990). Moreover, long-term studies of women with polycystic ovaries have shown an increase in diabetes and hypertension, and the central obesity phenotype in women carries an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (see Chapter 18, Polycystic ovary syndrome, for more information).

These metabolic factors are already well established during adolescence, as evidenced by the changes in bony structure. These must have been completed by the time of epiphyseal fusion at the end of the second decade. This was clearly demonstrated by Ferriman et al (1957) who noted that hirsute women had increased shoulder width and reduced bi-iliac width compared with non-hirsute women, and that these differences were greater in those women who noted that their hirsutism began during adolescence.

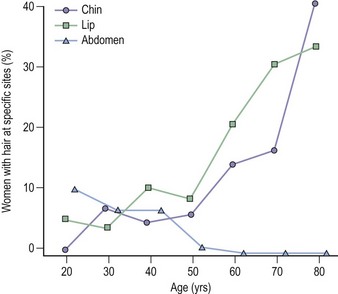

Postmenopausal women

A different strategy is required for postmenopausal women because, unlike younger women, they cannot be stratified on the basis of menstrual pattern. However, as women age, the pattern of facial and body hair changes (Figure 26.5); hair on the face increases whilst it involutes elsewhere. Hair growth on the chest, shoulders and upper back can be considered indications for further investigation. Hormonal changes in hirsute postmenopausal women are minor with small increases in testosterone compared with appropriate controls, so an elevated testosterone more than twice the upper limit of age-related normal or approximately 3.0 nmol/l should also be considered as a trigger for further investigation. Postmenopausal women with unexplained hirsuties have normal lipids, but women with ovarian hyperthecosis should be investigated further since they appear to have a very high incidence of glucose intolerance and vascular disease (Barth et al 1997).

Therapy for Hirsuties

Most women will be satisfied with the reassurance that they are not ‘turning into men’ and may not require any further medical attention. Some may need advice about local destructive methods and some may need to be advised how to use those methods. The vast majority of women have experience in at least one form of depilation (Toerien and Wilkinson 2005), so many women will be seeking medical help because they have already found these methods wanting. It is important to accept that the choice of therapies will depend on the needs and desires of the patient, and not the degree of hirsutism.

Psychological factors

There is a societal expectation in Western culture for women to be hairless, and hairiness in women is overwhelmingly constructed in a negative fashion. Is it surprising, therefore, that women regard their excess hair growth with unhappiness? They spend considerable amounts of time managing their facial hair and have high levels of emotional stress, depression and anxiety. Most concerning is their poor performance in social arenas and in relationships (Lipton et al 2006), leading to an overall poor quality of life (Barnard et al 2007). Some of the symptomatology can be explained by comorbidities such as obesity and acne (Barth et al 1993), which reinforces the need to treat holistically and to provide time and sympathy rather than considering hirsuties as a purely medical condition. In the author’s experience, only one-third of women want internal medical therapy after receiving a full explanation of their condition and informed advice about topical therapies.

Topical/cosmetic procedures

Hair bleaching with hydrogen peroxide and hair plucking are both useful and will have been used by most women prior to seeking medical help. Depilatory creams reduce the strength of the hair fibre by reducing the chemical sulphur–sulphur bonds which can then be sheared apart by rubbing the skin. Unfortunately, prolonged application, necessary for thick hairs, has the same effect on the stratum corneum and leads to redness and soreness. Shaving may be the only treatment that produces an acceptable cosmetic effect. This should be discouraged as no therapy can be as effective, and electrologists need a short stubble to direct their needles. There is no evidence that shaving has any effect on hair growth despite popular belief (Peereboom-Wynia 1972).

Weight reduction

Holistic lifestyle changes must be considered as a primary aim in all women with polycystic ovary syndrome and hirsuties for all the reasons of cardiovascular risk outlined above and also to reduce the risk of developing diabetes. Unfortunately, weight loss is difficult to achieve in many subjects despite the beneficial effects on all the risk factors viz. lipids, insulin resistance and blood pressure. Some subjects may benefit from treatment with weight-loss medication such as orlistat and sibutramine. There is only anecdotal evidence of the benefit of weight reduction on hair growth using holistic measures. Metformin, despite its ability to improve cardiometabolic status, does not improve hirsuties unless there is weight loss and cannot be recommended (Cosma et al 2008). Weight loss following bariatric surgery does, however, result in significant reduction in hair growth (Ecobar-Morreale et al 2005).

Systemic Antiandrogen Therapy

The coexistence of obesity in many hirsute women has been discussed above. Women who are overweight should be advised to reduce their weight since a reduction as small as 5% has been shown to be associated with both a regulation in menses and a reduction in hair growth. However, once a decision has been made to treat an hirsute woman, weight does not seem to play an important role in the efficacy of treatment (Crosby and Rittmaster 1991). Weight may be an important factor in the presentation of women with hirsuties, and should be considered in the treatment possibilities since weight gain or difficulty in weight loss is experienced with oral contraceptive therapy.

Oral contraceptive agents

Cyproterone acetate

Current dosage recommendations for CPA usually advise that 50 or 100 mg CPA should be administered for 10 days/cycle. However, three dose-ranging studies have suggested that there is no dose effect (Molinatti et al 1983, Belisle and Love 1986, Barth et al 1991).

Antiandrogenic compounds

Flutamide

Treatment with flutamide 250 mg twice daily, either as a sole agent or in combination with an oral contraceptive, results in reductions in hair scores after 1 year to values considered normal using the Ferriman and Gallwey scale. This therapeutic effect makes flutamide appear the most potent antiandrogen therapy, but flutamide, like all other antiandrogens, has serious hepatotoxic adverse effects (Wallace et al 1993). This adverse effect seems to develop in the first few weeks of therapy, and careful monitoring of liver function is recommended. The incidence of hepatotoxicity in males with prostate cancer is relatively low but fatal cases have occurred. At least one case of hepatic failure requiring liver transplantation has occurred as a direct result of treatment of an hirsute woman.

Other drugs

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids are first-line therapy for CAH and were the first endocrine therapy to be employed in the treatment of hirsuties with the rationale of suppressing the production of adrenal androgens. It is uncertain how effective they are at reducing androgenic hair growth in hirsute women, and despite subjective impressions of improvement, no objective improvement has been detected (Casey et al 1966). Moreover, glucocorticoids invariably increase insulin resistance and should theoretically worsen the hyperandrogenism.

Biochemical Monitoring of Androgen-Suppressive Therapy

KEY POINTS

Bardin CW, Lipsett MB. Testosterone and androstenedione blood production rates in normal women and in women with idiopathic hirsutism or polycystic ovaries. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1967;46:891-902.

Barnard L, Ferriday D, Guenther N, Strauss B, Balen AH, Dye L. Quality of life and psychological well being in polycystic ovary syndrome. Human Reproduction. 2007;22:2279-2286.

Barth JH. How hairy are hirsute women? Clinical Endocrinology. 1997;47:255-260.

Barth JH, Cherry CA, Wojnarowska F, Dawber RPR. Cyproterone acetate for severe hirsutism: results of a double-blind dose-ranging study. Clinical Endocrinology. 1991;35:5-10.

Barth JH, Catalan J, Cherry CA, Day AE. Psychological morbidity in women referred for treatment of hirsutism. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1993;37:615-619.

Barth JH, Jenkins M, Belchetz PE. Ovarian hyperthecosis, diabetes and hirsuties in post menopausal women. Clinical Endocrinology. 1997;46:123-128.

Barth JH, Yasmin E, Balen AH. The diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome: the criteria are insufficiently robust for clinical research. Clinical Endocrinology. 2007;67:811-815.

Batukan C, Muderris II, Ozcelik B, Ozturk A. Comparison of two oral contraceptives containing either drospirenone or cyproterone acetate in the treatment of hirsutism. Gynecological Endocrinology. 2007;23:38-44.

Belisle S, Love EJ. Clinical efficacy and safety of cyprotene acetate in severe hirsutism: results of a multicentred Canadian study. Fertility and Sterility. 1986;46:1015-1020.

Casey JH, Burger HG, Kent JR, et al. Treatment of hirsutism by adrenal and ovarian suppression. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1966;26:1370-1374.

Cosma M, Swiglo BA, Flynn DN, et al. Clinical review: insulin sensitizers for the treatment of hirsutism: a systematic review and metaanalyses of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2008;93:1135-1142.

Crosby PDA, Rittmaster RS. Predictors of clinical response in hirsute women treated with spironolactone. Fertility and Sterility. 1991;55:1076-1081.

Derksen J, Nagesser SK, Meinders AE, Haak HR, van de Velde CJH. Identification of virilising adrenal tumours in hirsute women. New England Journal of Medicine. 1994;331:968-973.

DeUgarte CM, Woods KS, Bartolucci AA, Azziz R. Degree of facial and body terminal hair growth in unselected black and white women: toward a population definition of hirsutism. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2006;91:1345-1350.

Escobar-Morreale HF, Botella-Carretero JI, Alvarez-Blasco F, Sancho J, San Millán JL. The polycystic ovary syndrome associated with morbid obesity may resolve after weight loss induced by bariatric surgery. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2005;90:6364-6369.

Ferriman D, Thomas PK, Purdie AW. Constitutional virilism. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 1957;ii:1410-1412.

Ferriman D, Gallwey JD. Clinical assessment of body hair growth in women. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology. 1961;21:1440-1447.

Kozloviene D, Kazanavicius G, Kruminis V. The evaluation of clinical signs and hormonal changes in women who complained of excessive body hair growth. Medicina (Kaunas). 2005;42:487-495.

Lipton M, Sherr L, Elford J, Rustin M, Clayton W. Women living with facial hair: the psychological and behavioral burden. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2006;61:161-168.

Lunde O, Grottum P. Body hair growth in women: normal or hirsute. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 1984;64:307-313.

Martin KA, Chang RJ, Ehrmann DA, et al. Evaluation and treatment of hirsutism in premenopausal women: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2008;93:1105-1120.

McKnight E. The prevalence of ‘hirsutism’ in young women. The Lancet. 1964;i:410-413.

Meldrum DR, Abraham GE. Peripheral and ovarian venous concentration of various steroid hormones in virilising ovarian tumours. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1979;53:36-43.

Molinatti GM, Messina M, Manieri C, Massuchetti C, Biffignandi P. Current approaches to the treatment of virilizing syndromes. In: Molinatti GM, Martini L, James VHT, editors. Androgenization in Women. New York: Raven Press; 1983:179-193.

Moran C, Tapia MC, Hernandez E, Vazquez G, Garcia-Hernandez E, Bermudez JA. Etiological review of hirsutism in 250 patients. Archives of Medical Research. 1994;25:311-314.

O’Driscoll JB, Mamtora H, Higginson J, Pollock A, Kane J, Anderson DC. A prospective study of the prevalence of clear-cut endocrine disorders and polycystic ovaries in 350 patients presenting with hirsutism or androgenic alopecia. Clinical Endocrinology. 1994;41:231-236.

Peereboom-Wynia JDR. The effect of various methods of epilation on density of hair growth in women with idiopathic hirsutism. Archiv fuer Dermatologische Forschung. 1972;243:164-176.

Rosner W, Auchus RJ, Azziz R, Sluss PM, Raff H. Utility, limitations, and pitfalls in measuring testosterone: an Endocrine Society position statement. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2007;92:405-413.

Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Human Reproduction. 2004;19:41-47.

Shah PN. Human body hair — a quantitative study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1957;73:1255-1265.

Spritzer P, Billaud L, Thalabard J-C, et al. Cyproterone acetate versus hydrocortisone treatment in late-onset adrenal hyperplasia. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1990;70:642-646.

Thomas PK, Ferriman DG. Variation in facial and pubic hair growth in white women. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 1957;15:171-180.

Toerien M, Wilkinson S, Choi PYL. Body hair removal: the ‘mundane’ production of normative femininity. Sex Roles. 2005;52:399-406.

Toscano V, Adamo MV, Caiola S, et al. Is hirsutism an evolving syndrome? Journal of Endocrinology. 1983;97:379-387.

Wallace C, Lalor EA, Chik CL. Hepatotoxicity complicating flutamide treatment of hirsutism. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1993;118:1150.

Wild RA, Grubb B, Hartz A, van Nort JJ, Bachman W, Bartholomew M. Clinical signs of androgen excess as risk factors for coronary disease. Fertility and Sterility. 1990;54:255-259.