20 Herbal and Nutritional Supplements for Painful Conditions

Herbs and supplements are widely used by patients in pain.1 Throughout this chapter, mechanisms of action and efficacy, dosing, and safety information will be provided for each herb, supplement, and natural product for the pain syndromes for which research literature supports their use. For herbs, the medicinal portion of the plant will also be given because different parts of a plant may have different constituents and clinical effects. This chapter is meant to provide an overview, and practitioners not already trained in natural medicine should seek additional education to become proficient in the use of natural products.

Natural substances offer many potential benefits for helping treat patients with pain. First, they often have long histories of use (thousands of years in some cases; the Ebers Papyrus, arguably the oldest book in the world, consists of a materia medica of traditional Egyptian medicine2), and one could argue these substances are among the best tested and most “evidence-based” medicines available.3 Second, they are largely nontoxic, although there are exceptions.4 One study found that over a 10-year period, only two deaths in the United States could be linked to herbal medicines.5 Third, they are often cost effective, again, with exceptions. Finally, they act on multiple pathways, some of which are not addressed by any other existing therapies.6 Study of the mechanism of action of some natural treatments has led to breakthroughs in the understanding of pain pathophysiology and to the development of entirely new categories of medications. For example, investigation of capsaicin brought about enhanced understanding of vanilloid receptors, TRPV1, unmyelinated C fibers, substance P, and novel topical treatments for pain syndromes.7

Western Herbal Medicine: Complexity and Synergy

Herbs have been an important part of Western medicine for thousands of years.8,9 Herbs contain hundreds of different compounds, and traditional medicine theorizes that the constituents of medicinal plants act synergistically.10 Many studies support that complex herbal extracts often have effects that are distinct and/or greater than those of their single isolated constituents.11

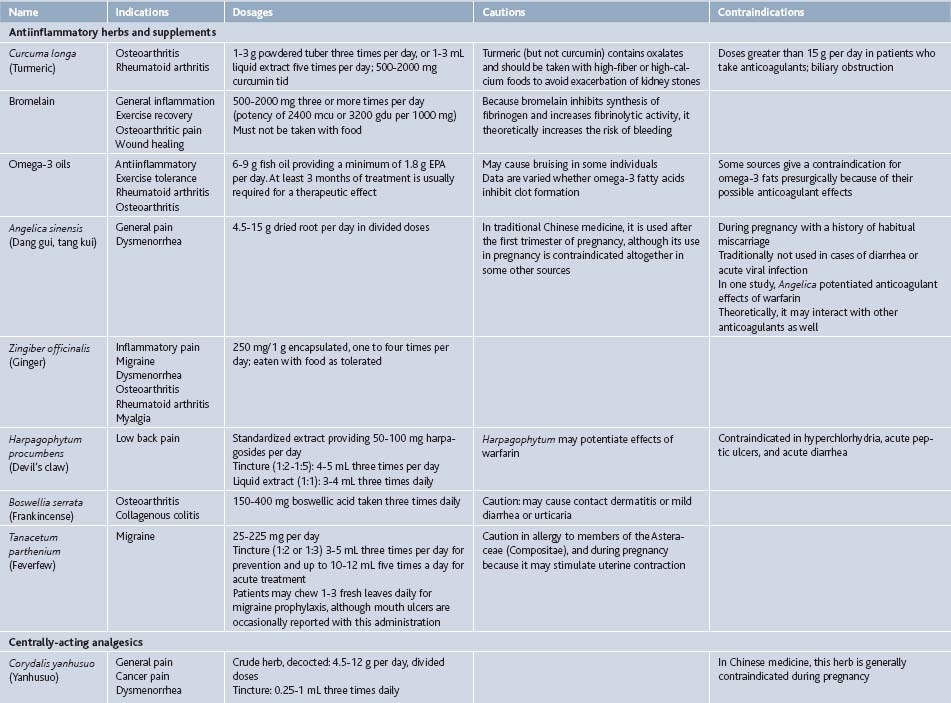

In some cases, isolated compounds or highly refined extracts with just a few constituents such as silymarin, a complex of three flavonoligans from Silybum marianum (milk thistle) seed, or curcumin, a mixture of three resinous polyphenols from Curcuma longa (turmeric) rhizome, are used clinically. It is not clear if these offer advantages over more complex, less concentrated extracts, given a near total lack of comparative studies, but such extracts do satisfy the demand for uniformity, simplicity, and patentability prevalent in a market-driven health care system and society.12 Throughout this chapter, both refined and crude herbal extracts will be listed for completeness, although often it is unknown which form is superior (Table 20-1).

Chinese Herbal Medicine: Ancient and Modern

Chinese medicine is one of the most ancient healing systems on the planet.13,14 Based on a distinctive physiology quite unlike Western medicine, it is still in use today. Herbs play a central role in Chinese medicine, although acupuncture is more widely accepted in Western society. Unlike in Western cultures, herbs in traditional Chinese medicine are almost always given in complex formulas,15 as it was observed that combining herbs produces a stronger, more specific therapeutic effect, and that herbs used together mitigate some of the adverse effects they may engender as single entities. Formulation is still the most common way to prescribe Chinese herbs.16 Nevertheless, biochemical and pharmaceutical research techniques have been extensively applied to Chinese herbs, and now single-herb medicines or isolated constituents extracted from single herbs are used more widely. Caution is warranted with these much more recent innovations, and the traditional formulas are preferred in most cases. Many of these same arguments could be made about traditional medicine systems from around the world, such as Ayurveda and Unani-Tibb in South Asia, or Native American medicine.

Antiinflammatory Herbal Medicines

Curcuma Longa (Turmeric)

The rhizome of Curcuma longa is ground or tinctured (1:2 ratio, >45% ethanol content)6 to make medicine. Most supplements use curcumin, a mixture of lipophilic polyphenolic compounds including diferuloylmethane, demethoxycurcumin and bisdemethoxycurcumin found in the rhizome. It is traditionally used for pain and has been shown to modulate inflammatory cytokines including IL-1β, IL-12, IL-6, TNF-α, and IFN-γ.17

Bromelain

Bromelain is a mixture of enzymes derived from pineapple. Its effects are mainly a product of its proteolytic activity, which stimulates fibrinolysis by increasing plasmin, but bromelain also has been shown to prevent kinin production and to inhibit platelet aggregation.22 Because its mechanism of action is generally antiinflammatory, rather than specific to a particular disease process, bromelain is used to treat a variety of pain and inflammatory conditions. When given to treat pain, it must be administered away from food because it will act as a digestive enzyme if consumed with food.

Omega-3 Oils

Omega-3 essential fatty acids are used by the body to form cell membranes and antiinflammatory prostaglandins, among other important molecules. Murine studies indicate that these fats produce resolvins and protectins, novel lipids with antiinflammatory properties. Although these fatty acids do not act specifically on nociceptive pathways, their administration has the well-documented effect of reducing inflammation in the body.30

A study comparing two marine oils (seal and cod liver oils) found no difference in their efficacy,31 suggesting that the origin of the fatty acids is less important than their EPA/DHA content. Fatty acid source is a concern with regard to heavy metal and PCB content of the supplements, and only products that employ third-party verification of purity should be given.

Angelica sinensis (Dang Gui, Tang Kui, Dong Kuai)

The root is used as medicine and the herb is tinctured, decocted, or powdered and encapsulated. In China, it is also injected locally into areas of low back and postsurgical pain with significant improvement of symptoms.36 Angelica is commonly used in Chinese medicine for gynecologic complaints, including dysmenorrhea. Active constituents include ligustilide, which has been demonstrated in murine studies to be antinociceptive and antiinflammatory.37

Zingiber officinalis (Ginger)

The rhizome of Zingiber has been used in traditional Asian medicines, including Chinese and Ayurvedic herbalism, for millennia. Today, it is administered as encapsulated powder, in decoction, food, or tincture. Ginger is more commonly used for treatment of digestive complaints than it is for pain, but has been shown to inhibit prostaglandin and thromboxane formation in platelets39 and serotonin receptors in vivo. In vitro studies of human synoviocytes have demonstrated that Zingiber extract inhibits TNF-α activation and cyclooxygenase-2 expression.40

Harpagophytum procumbens (Devil’s Claw)

This herb is native to southern Africa, and it grows in a fairly limited distribution, making it somewhat threatened in the wild. Because of this, only cultivated material should be purchased. The tuber is used therapeutically, and active constituents appear to be iridoid glycosides including harpagosides. This herb is usually administered as an aqueous or alcohol extract. Mechanism of action is unknown, but appears to be mediated via the central nervous system with possible peripheral antinociceptive effects. A rodent study found that its effects were attenuated by naloxone administration, suggesting that it acts at least in part via opioidergic pathways.47

Boswellia serrata (Frankincense)

Tanacetum parthenium (Feverfew)

The leaf is typically used as medicine and is eaten fresh or taken as tea, encapsulated crude herb or tincture. It appears to act by inhibiting formation of prostaglandins in the arachidonic acid pathway, inhibiting serotonin and histamine secretion, preventing platelet aggregation, or by reducing vascular response to vasoactive amines. Parthenolide is supposedly one of the major active constituents and appears to inhibit arachidonic acid release, but studies using parthenolide alone do not yield the clinical results obtained by administration of the whole herb.52

Centrally-Acting Herbs and Supplements

Corydalis yanhusuo

A member of the poppy family, Corydalis yanhusuo is one of traditional Chinese medicine’s chief herbs for relieving pain. The rhizome is used. Like many Chinese herbs, it is traditionally taken as an aqueous extract (i.e., decocted as tea, although it is also given as tincture [1:3 to 1:5]) or in pill or capsule form. Substitution of other species of Corydalis for C. yanhusuo is not recommended because their actions appear to differ. Its primary active constituents are alkaloids, including berberine, corydaline, and tetrahydropalmatine. Various studies have compared Corydalis extracts to morphine and findings vary, indicating that they have from 1% to 40% the analgesic effect of morphine.16,22,54

Cannabis sativa

Research into the mechanism of cannabinoid receptors in the body is ongoing, but suggests that they play a role in the pain-mediating effects of cannabinoids. Two major types of receptors, CB1 (found primarily in the nervous system, both centrally and peripherally) and CB2 (found in nonnervous tissues, including immune cells), have been identified.57

Hypericum perforatum (St. John’s Wort)

The aerial parts of the plant are used as medicine. Hypericum may be given internally as a tincture, decoction, or encapsulation, or used topically as a lotion. Hypericin, hyperforin, and flavonoids are thought to be the major active constituents. This herb is most commonly associated with treatment of depression but eclectic physicians used it topically as a vulnerary and internally to treat neurogenic pain, including sciatica and rheumatic pain.71

Two murine studies demonstrated antinociceptive properties of H. perforatum. These properties are dose-dependent in a bell-shaped trend, i.e., therapeutic effect may only be derived from doses that are neither too low nor too high. Hypericum’s mechanism of nociceptive action seems to be due to hypericin’s inhibition of protein kinase C and to interaction with opioid receptors, although other receptor classes may be involved.72 Opioid receptor involvement is supported by the finding that the herb significantly enhances the effects of concurrently administered morphine without altering serum morphine levels.47

Topical Herbs and Supplements

Capsicum frutescens (Cayenne)

Capsaicin is the major active constituent of the cayenne pepper, Capsicum frutescens and Capsicum annuum. It is chiefly applied topically, either in patches or in ointment form. Commercial creams or ointments are available in 0.025% and 0.075% capsaicin concentrations. Capsaicin works as a counterirritant. It stimulates small-diameter pain fibers, thereby depleting them of substance P and preventing transmission of pain signals from the peripheral to the central nervous system.22 In studies of treatment for peripheral neuropathy, for instance, patients experienced benefit after 4 to 6 weeks of use, although a high-dose topical patch resulted in immediate improvement in one study.80 Some studies concluded that capsaicin was a poor therapy but application of capsaicin was observed only for 3 or 4 weeks. Patients may experience adverse effects on initial use.

Successful treatment with capsaicin has been most commonly reported in conditions affecting topical nerves, including postherpetic neuralgia,53 diabetic neuropathy, arthritis, mouth pain following chemotherapy and radiation, postmastectomy pain, and trigeminal neuralgia. However, capsicum has also been used to successfully treat cluster headaches after intranasal application.81

Urtica dioica (Stinging Nettle)

All parts of the Urtica plant are used as medicine, although only the leaves are used to treat pain. Fresh leaves are used topically for pain as a counterirritant. Urtica leaves are covered with fine hairs with a high silicon content that break when touched and release a toxin into the skin. Like apitherapy, therapeutic effect is achieved by stinging the affected area (urtication). The toxin contains several chemicals including histamine, acetylcholine, and serotonin, and provokes urticaria and C fiber discharge.82

Symphytum officinale (Comfrey)

Herbalists have long used Symphytum root and leaf topically and internally for treatment of pain and osseous fractures. Symphytum is available in cream, ointment, and gel forms for topical use. Active constituents include rosmarinic acid, mucopolysaccharides, allantoin, and mucilage. The discovery of unsaturated pyrrolizidine alkaloids (uPA), which are potentially hepatotoxic and carcinogenic, in Symphytum has led to the recommendation that this herb be used only topically and on intact skin. uPA are absorbed only very minimally during dermal application. The herb is still used internally for short periods because studies indicate that the alkaloids cause genetic damage only in long-term use (several months or more).71,84 uPA-free extracts may be used indefinitely.

Arnica montana

Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO)

DMSO is an organic solvent with a variety of pharmaceutical actions, including analgesic, diuretic, bacteriostatic, membrane-penetrant, antiinflammatory, vasodilatory, and cholinesterase inhibitory effects.89 Data about DMSO’s analgesic effects on its own are mixed. However, when DMSO is used as a carrier for other analgesics, it increases these agents’ efficacy (in one study, lidocaine,90 in another, diclofenac)91 and reduces their morbidity.

Echinacea spp. (Purple Coneflower)

The aerial parts of Echinacea may be tinctured and used as a gargle. Besides its use as an antimicrobial, extracts of Echinacea can have a numbing effect and may be used to treat pharyngeal pain. An Echinacea/sage throat spray was found to be as effective and as well-tolerated as chlorhexidine/lidocaine in treatment of acute sore throats.93

Salicylate-Containing Herbal Medicines

Salix alba (White Willow)

Hypnotic Analgesic Herbs and Supplements

Valeriana officianalis (Valerian)

Although Valeriana is more commonly associated with treatment of insomnia, it has also traditionally been used for treatment of general pain and headache.6,99

Piscidia piscipula, P. erythrina (Jamaican Dogwood)

Used traditionally to treat pain, these Piscidia species are antispasmodic, hypnotic, and anodyne. The medicinal part, the root bark, is taken as a crude herb, tinctured or administered as an aqueous extract. Aqueous extract appears to be the most potent of the extractions.100 Active constituents primarily appear to be rotenoids and isoflavones, the latter category including piscidone, piscerythrone, and tetrahydroxy-methoxy-diisoprenyl-isoflavone (DPI).

These herbs are commonly used in medical herbalist practice, for example for migraine, dysmenorrhea, rheumatic pain, neuralgia, sciatica, and spastic pain, but few human studies have been performed to evaluate their use. Animal studies demonstrate that the fluid extract decreases the amplitude of intestinal contractions.101 DPI, piscidone and piscerythrone had spasmolytic effects against oxytocin-induced contractions in rat uteri.102

Symptoms of toxicity include sweating, numbness, tremors, and excessive salivation.

Eschscholtzia californica (California Poppy)

The aerial parts of the plant have been used as a hypnotic anodyne traditionally. Its hypnotic effects have been confirmed in the research literature, but few comprehensive clinical studies have been performed on Eschscholtzia to examine its role in pain management. It is taken internally, most commonly as a tincture or decoction.6 Although a member of the Papaveraceae family, it is traditionally regarded as one of the safest and most gentle of the anodynes and may be given to children.103

Nutritional Cofactors

Methylsulfonylmethane (MSM)

Riboflavin

Lipoic Acid/Alpha Lipoic Acid/Thioctic Acid

Lipoic acid is a disulfide produced in the body. It is a small, easily absorbed molecule and is a potent antioxidant that increases the activity of catalase and superoxide dismutase in peripheral nerves, is neurogenerative and normalizes endoneural blood flow. Because it is both lipophilic and hydrophilic, it addresses both fat- and water-soluble free radical species. It is administered orally and intravenously. Coadministration of a B-complex supplement is recommended because lipoic acid may deplete these vitamins.107

S-adenosyl methionine (SAM-e)

SAM-e is the stable salt form of S-adenosyl methionine, a methyl donor produced from methionine and adenosine triphosphate in the liver. It is commonly used to treat depression, a condition in which CSF SAM-e levels tend to be low, compared to nondepressed individuals.109 SAM-e increases turnover of serotonin and may increase levels of dopamine and norepinephrine.

Glucosamine Sulfate and Chondroitin Sulfate

Chondroitin plays a number of roles in connective tissue synthesis. It is itself a glycosaminoglycan and, when hydrated, it creates osmotic pressure that increases the compressive resistance of synovial cartilage. It also stimulates the production of collagen and proteoglycan and inhibits enzymatic destruction of the synovium.22,111

Magnesium

Hormonal Analgesics

Melatonin

Research on melatonin has examined the hormone’s influence on nonendocrine tissues and has elucidated the mechanism by which it might influence pain. It is present throughout the central nervous system, and has been shown to treat acute, inflammatory, and neuropathic pain symptoms.121

Vitamin D

Although vitamin D is a nonessential vitamin, recent research has demonstrated epidemic deficiency of this vitamin in the general population, especially in the elderly, institutionalized populations, those who live in northern latitudes, with limited sun exposure or who have dark skin. It is available in pill, capsule, powder, and liquid forms. Vitamin D deficiency has been linked with a variety of painful disease states, including bone loss and attendant fractures,125 pelvic floor disorders,126 systemic lupus erythematosus,127 tuberculosis, certain cancers, and inflammatory bowel diseases.128 A 2008 review article, however, found that studies demonstrating a link between hypovitaminosis D and chronic pain were largely of poor quality and that too few randomized controlled trials had been performed.129 Although vitamin D2 (ergocalciferol) and D3 (cholecalciferol) are both available commercially, the D3 form of the vitamin is more potent and has longer-lasting effects.130

Vitamin D intoxication is reported rarely, and published cases all involve persons who consumed at least 40,000 IU per day long-term. Evidence suggests that the currently accepted No Adverse Effect Limit of 2000 IU per day is probably too low “by at least five fold.” No adverse effects are seen in individuals who are not hypersensitive when serum levels of 25(OH)D are less than 140 nmol/L (56 ng/mL), which is attained in healthy people by consuming 10,000 IU per day long term.131 Another study whose subjects’ serum concentrations reached 400 nmol/L reported no observable hypercalcemia, hypercalciuria or adverse effects.132 Although dosages of 10,000 IU per day may be taken long-term without major problems, very large single doses of vitamin D are not recommended. A study in which a massive single dose of vitamin D (500,000 IU) was given to women older than age 70 with normal baseline serum levels demonstrated that such high doses increased the risk of fracture and falling.133

Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10)

Coenzyme Q10 acts as a mitochondrial electron-transport chain cofactor in the reactions that produce ATP. It scavenges free radicals and is a component of the Krebs cycle enzyme succinate dehydrogenase-coQ10. Its alternate name, ubiquinone, reflects its omnipresence throughout the body. Despite the fact that coQ10 is synthesized innately, it is commonly deficient in the general population.22 Its production decreases with age and it is depleted by many pharmaceuticals, including beta blockers, antipsychotics, some statins, metformin, sulfonylureas, and some tricyclic antidepressants.118 Animal studies demonstrate that its antinociceptive effects may be a consequence of its downregulation of nitric oxide.144 Two forms are available commercially—ubiquinone and ubiquinol (ubiquinone’s reduced form). Ubiquinol is more commonly given clinically.

Miscellaneous Agents

Ginkgo biloba (Ginkgo)

Centella asiatica (Gotu Kola)

Centella has been used in traditional herbal medicines across Asia. The whole plant is used, and dosage forms include encapsulation of the crude herb, decoction, and tinctures. Active constituents include triterpenoid saponins and notable amounts of asiaticoside, madecassoside and madecassic acid. A murine study demonstrated that the crude herb possesses antiinflammatory and antinociceptive properties. Its effects were likely mediated by the central and peripheral nervous systems and its mechanism of action may involve opioid receptors.154

Viburnum opulus (Cramp Bark), Viburnum prunifolium (Black Haw)

Scutellaria laterifolia (Skullcap)

Scutellaria baicalensis (Huang qin)

Rosa canina

Solidago chilensis (Brazilian Arnica)

The leaves and flowers of Solidago have long been used as medicine by indigenous Brazilians. Active constituents include flavonoids, carotenes, and diterpenoids. Mouse studies demonstrate that the rhizome also possesses potent antiinflammatory activity.160

1. Bücker B., Groenewold M., Schoefer Y., Schäfer T. The use of complementary alternative medicine (CAM) in 1 001 German adults: Results of a population-based telephone survey. Gesundheitswesen. 2008;70(8-9):e29-e36.

2. Ebbell B. The Papyrus Ebers: The Greatest Egyptian Medical Document. Copenhagen: Levin & Munskgaard; 1937.

3. Court W.E. A history of herbal medicine. Pharm Hist (Lond). 1985;15(2):6-8.

4. Yang S., Dennehy C.E., Tsourounis C. Characterizing adverse events reported to the California Poison Control System on herbal remedies and dietary supplements: A pilot study. J Herb Pharmacother. 2002;2(3):1-11.

5. Woolf A.D., Watson W.A., Smolinske S., Litovitz T. The severity of toxic reactions to ephedra: Comparisons to other botanical products and national trends from 1993-2002. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2005;43(5):347-355.

6. Yarnell E. Phytotherapy for the treatment of pain. Modern Phytotherapist. 2002;7(1):3-12.

7. Kam P.C.A., Hayman M. Capsaicin: A review of its pharmacology and clinical applications. Curr Anaesthes Crit Care. 2008;19:338-343.

8. Becky L.Y. De Materia Medica by Pedianus Dioscorides. Hildesheim, Germany: Olms-Weidmann. 2005.

9. Scarborough J. Theophrastus on herbals and herbal remedies. J Hist Biol. 1978;11(2):353-385.

10. Spelman K. Philosophy in Phytopharmacology: Ockham’s Razor versus Synergy. J Herb Pharmacother. 2005;5:31-47.

11. Ma X.H., Zheng C.J., Han L.Y., et al. Synergistic therapeutic actions of herbal ingredients and their mechanisms from molecular interaction and network perspectives. Drug Discov Today. 2009;14(11-12):579-588.

12. Brinker F.J. Complex Herbs, Complete Medicines. Sandy, Ore: Eclectic Medical; 2004.

13. Zheng B.C. Shennong’s herbal—one of the world’s earliest pharmacopoeia. J Tradit Chin Med. 1985;5(3):236.

14. Liu Z.Z. Shen Nong’s Herbal, the earliest extant treatise on Chinese materia medica. Zhong Yao Tong Bao. 1982;7(5):43-45.

15. Hou J.P. The development of Chinese herbal medicine and the Pen-ts’ao. Comp Med East West. 1977;5(2):117-122.

16. Bensky D., Clavey S., Stöger E. Chinese herbal medicine materia medica, 3rd ed. Seattle: Eastland Press; 2004.

17. Bright J.J. Curcumin and autoimmune disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;595:425-451.

18. Kuptniratsaikul V., Thanakhumtorn S., Chinswangwatanakul P., et al. Efficacy and safety of Curcuma domestica extracts in patients with knee osteoarthritis. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15(8):891-897.

19. Park C., Moon D.O., Choi I.W., et al. Curcumin induces apoptosis and inhibits prostaglandin E(2) production in synovial fibroblasts of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Mol Med. 2007;20(3):365-372.

20. Tang M., Larson-Meyer D.E., Liebman M. Effect of cinnamon and turmeric on urinary oxalate excretion, plasma lipids, and plasma glucose in healthy subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:1262-1267.

21. Mills S., Bone K. The essential guide to herbal safety. St Louis: Elsevier; 2005.

22. Pizzorno J.E., Murray M.T. Textbook of Natural Medicine, 3rd ed. St Louis: Churchill Livingstone; 2006.

23. Miller P.C., Bailey S.P., Barnes M.E., et al. The effects of protease supplementation on skeletal muscle function and DOMS following downhill running. J Sport Sci. 2004;22:365-372.

24. Stone M.B., Merrick M.A., Ingersoll C.D., Edwards J.E. Preliminary comparison of bromelain and ibuprofen for delayed onset muscle soreness management. Clin J Sport Med. 2002;12:373-378.

25. Walker A.F., Bundy R., Hicks S.M., Middleton R.W. Bromelain reduces mild acute knee pain and improves well-being in a dose-dependent fashion in an open study of otherwise healthy adults. Phytomedicine. 2002;9:681-686.

26. Akhtar N.M., Naseer R., Farooqi A.Z., et al. Oral enzyme combination versus diclofenac in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee—a double-blind prospective randomized study. Clin Rheumatol. 2004;23:410-415.

27. Brien S., Lewith G., Walker A., et al. Bromelain as a treatment for osteoarthritis: A review of clinical studies. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2004;1:251-257.

28. MacKay D., Miller A.L. Nutritional support for wound healing. Altern Med Rev. 2003;8:359-377.

29. Lotz-Winter H. On the pharmacology of bromelain: An update with special regard to animal studies on dose-dependent effects. Planta Med. 1990;56:249-253.

30. Goldberg R.J., Katz J. A meta-analysis of the analgesic effects of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation for inflammatory joint pain. Pain. 2007;129:210-223.

31. Brunborg L.A., Madland T.M., Lind R.A., et al. Effects of short-term oral administration of dietary marine oils in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and joint pain: A pilot study comparing seal oil and cod liver oil. Clin Nutr. 2008;27:614-622.

32. Tartibian B., Maleki B.H., Abbasi A. The effects of ingestion of omega-3 fatty acids on perceived pain and external symptoms of delayed onset muscle soreness in untrained men. Clin J Sport Med. 2009;19:115-119.

33. Peoples G.E., McLennan P.L., Howe P.R., Groeller H. Fish oil reduces heart rate and oxygen consumption during exercise. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2008;52:540-547.

34. Gajos G., Rostoff P., Undas A., Piwowarska W. Effects of polyunsaturated omega-3 fatty acids on responsiveness to dual antiplatelet therapy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: The OMEGA-PCI (Omega-3 fatty acids after PCI to modify responsiveness to dual antiplatelet therapy) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1671-1678.

35. Bender N.K., Kraynak M.A., Chiquette E., et al. Effects of marine fish oils on the anticoagulant status of patients receiving chronic warfarin therapy. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 1998;5:257-261.

36. Chen JK, Chen TT. Chinese medical herbology and pharmacology. City of Industry, Calif; Art of Medicine; 2004.

37. Du J., Yu Y., Ke Y., et al. Ligustilide attenuates pain behavior induced by acetic acid or formalin. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;112:211-214.

38. Yuan C.S., Mehendale S.R., Wang C.Z., et al. Effects of Corydalis yanhusuo and Angelicae dahuricae on cold pressor-induced pain in humans: A controlled trial. J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;44(11):1323-1327.

39. Mustafa T., Srivastava K.C. Ginger (Zingiber officinale) in migraine headaches. J Ethnopharmacol. 1990;29:267-273.

40. White B. Ginger: An overview. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75:1689-1691.

41. Cady R.K., Schreiber C.P., Beach M.E., Hart C.C. Gelstat migraine (sublingually administered feverfew and ginger compound) for acute treatment of migraine when administered during the mild pain phase. Med Sci Monit. 2005;11:PI65-PI69.

42. Ozgoli G., Goli M., Moattar F. Comparison of effects of ginger, mefenamic acid and ibuprofen on pain in women with primary dysmenorrhea. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15:129-132.

43. Jiang X., Williams K.M., Liauw W.S., et al. Effect of ginkgo and ginger on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of warfarin in healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;59:425-432.

44. Bordia A., Verma S.K., Srivastava K.C. Effect of ginger (Zingiber officinale Rosc.) and fenugreek (Trigonella foenumgraceum L.) on blood lipids, blood sugar, and platelet aggregation in patients with coronary artery disease. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 1997;56:379-384.

45. Verma S.K., Bordia A. Ginger, fat and fibrinolysis. Indian J Med Sci. 2001;55:83-86.

46. Janssen P.L., Meyboom S., van Staveren W.A., et al. Consumption of ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) does not affect ex vivo platelet thromboxane production in humans. Eur J Clin Nutr. 50, 1996. 772-724

47. Uchida S., Hirai K., Hatanaka J., et al. Antinociceptive effects of St. John’s Wort, Harpagophytum procumbens and grape seed proanthocyanidins extract in mice. Biol Pharm Bull. 2008;31:240-245.

48. Van Tulder M.W., Furlan A.D., Gagnier J.J. Complementary and alternative therapies for low back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2005;19:639-654.

49. Sontakke S., Thawani V., Pimpalkhute S., et al. Open, randomized, controlled clinical trial of Boswellia serrata extract as compared to valdecoxib in osteoarthritis of the knee. Indian J Pharmacol. 2007;39:27-29.

50. Sengupta K., Alluri K.V., Satish A.R., et al. A double blind randomized placebo controlled study of the efficacy and safety of 5-Loxin for treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10(4):R85.

51. Madisch A., Miehlke S., Eichele O., et al. Boswellia serrata extract for the treatment of collagenous colitis. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:1445-1451.

52. Supernaw RB. Cayenne and feverfew: Popular herbals for pain care. Pain Practitioner. 2000;10:8-9.

53. Rakel D. Integrative Medicine, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2007.

54. Chang H.M., But P.P.H., editors. Pharmacology and Applications of Chinese Materia Medica, vol. 1. Philadelphia: World Scientific, 1986.

55. Gao J.L., Shi J.M., Lee S.M., et al. Angiogenic pathway inhibition of Corydalis yanhusuo and berberine in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Oncol Res. 2009;17:519-526.

56. Gao J.L., He T.C., Li Y.B., Wang Y.T. A traditional Chinese medicine formulation consisting of Rhizoma Corydalis and Rhyzoma Curcumae exerts synergistic anti-tumor activity. Oncol Rep. 2009;22:1077-1083.

57. Walsh D., Nelson K.A., Mahmoud F.A. Established and potential therapeutic applications of cannabinoids in oncology. Support Care Cancer. 2003;11:137-143.

58. Holdcroft A., Maze M., Doré C., et al. A multicenter dose-escalation study of the analgesic and adverse effects of an oral cannabis extract (Cannador) for postoperative pain management. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:1040-1046.

59. Rahn E.J., Hohmann A.G. Cannabinoids as pharmacotherapies for neuropathic pain: From the bench to the bedside. Neurotherapeutics. 2009;6:713-737.

60. Comelli F., Bettoni I., Colleoni M., et al. Beneficial effects of a Cannabis sativa extract treatment on diabetes-induced neuropathy and oxidative stress. Phytother Res. 2009;12:1678-1684.

61. Berman J.S., Symonds C., Birch R. Efficacy of two cannabis based medicinal extracts for relief of central neuropathic pain for brachial plexus avulsion: Results of a randomised controlled trial. Pain. 2004;112:299-306.

62. Kenner M., Menon U., Elliot D.G. Multiple sclerosis as a painful disease. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2007;79:303-321.

63. Lakhan S.E., Rowland M. Whole plant cannabis extracts in the treatment of spasticity in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. BMC Neurol. 2009;9:59.

64. Blake D.R., Robson P., Ho M., et al. Preliminary assessment of the efficacy, tolerability, and safety of a cannabis-based medicine (Sativex) in the treatment of pain caused by rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 2006;45:50-52.

65. Elikkottil J., Gupta P., Gupta K. The analgesic potential of cannabinoids. J Opiod Manag. 2009;5(6):341-357.

66. Karst M., Wippermann S. Cannabinoids against pain. Efficacy and strategies to reduce psychoactivity: A clinical perspective. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;18(2):125-133.

67. Dragt S., Nieman D.H., Becker H.E., et al. Age of onset of cannabis use is associated with age of onset of high-risk symptoms for psychosis. Can J Psychiatry. 2010;55(3):165-171.

68. Welch K.A., McIntosh A.M., Job D.E., et al. The impact of substance use on brain structure in people at high risk of developing schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2010 Mar 11. [Epub ahead of print]

69. Wallace M., Schulteis G., Hampton Atkinson J., et al. Dose-dependent effects of smoked cannabis on capsaicin-induced pain and hyperalgesia in healthy volunteers. Anesthesiology. 2007;107:785-796.

70. Hezode C., Roudot-Thoraval F., Nguyen S., et al. Daily cannabis smoking as a risk factor for progression of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2005;42:63-71.

71. Hoffman D. Medical Herbalism. Rochester, Vermont: Healing Arts Press; 2003.

72. Galeotti N., Vivoli E., Bilia A.R., et al. A prolonged protein kinase C-mediated, opioid-related antinociceptive effect of Saint John’s wort in mice. J Pain. 2010;11:149-159.

73. Sarrell E.M., Mandelberg A., Cohen H.A. Efficacy of naturopathic extracts in the management of ear pain associated with acute otitis media. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155(7):796-799.

74. Sarrell E.M., Cohen H.A., Kahan E. Naturopathic treatment for ear pain in children. Pediatrics. 2003;111(5 Pt 1):E574-E579.

75. Sardella A., Lodi G., Demarosi F., et al. Hypericum perforatum extract in burning mouth syndrome, a randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Oral Pathol Med. 2008;37:395-401.

76. Galeotti N., Vivoli E., Bilia A.R., et al. St. John’s wort reduces neuropathic pain through a hypericin-mediated inhibition of the protein kinase C gamma and epsilon and activity. BiochemPharmacol. 2010;79:1327-1336.

77. Sindrup S.H., Madsen C., Bach F.W., et al. St. John’s wort has no effect on polyneuropathy. Pain. 2000;91:361-365.

78. Jiang X., Williams K.M., Liauw W.S., et al. Effect of St John’s wort and ginseng on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of warfarin in healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;57:592-599.

79. Izzo A.A., Ernst E. Interactions between herbal medicines and prescribed drugs: An updated systematic review. Drugs. 2009;69(13):1777-1798.

80. Backonja M., Wallace M.S., Blonsky E.R., et al. NGX-4010, a high-concentration capsaicin patch, for the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia: A randomised, double-blind study. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:1106-1112.

81. Fusco B.M., Barzoi G., Agrò F. Repeated intranasal capsaicin applications to treat chronic migraine. Br J Anaesth. 2003;90:812.

82. Alford L. The use of nettle stings for pain. Altern Ther Health Med. 2007;13:58.

83. Randall C., Randall H., Dobbs F., et al. Randomized controlled trial of nettle sting for base-of-thumb pain. J R Soc Med. 2000;93:305-309.

84. Betz J.M., Eppley R.M., Taylor W.C., Andrzejewski D. Determination of pyrrolizidine alkaloids in commercial comfrey products (Symphytum sp.). J Pharm Sci. 1994;83:649-653.

85. Kucera M., Barna M., Horàcek O., et al. Topical symphytum herb concentrate cream against myalgia: A randomized controlled double-blind clinical study. Adv Ther. 2005;22:681-692.

86. Grube B., Grünwald J., Krug L., Staiger C. Efficacy of a comfrey root (Symphyti offic. radix) extract ointment in the treatment of patients with painful osteoarthritis of the knee: Results of a double-blind, randomised, bicenter, placebo-controlled trial. Phytomedicine. 2007;14:2-10.

87. Leu S., Havey J., White L.E., et al. Accelerated resolution of laser-induced bruising with topical 20% arnica: A rater-blinded randomized controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:557-563.

88. Widrig R., Suter A., Saller R., Melzer J. Choosing between NSAID and arnica for topical treatment of hand osteoarthritis in a randomised, double-blind study. Rheumatol Int. 2007;27:585-591.

89. Wein A.J., editor. Campbell-Walsh Urology, 9th ed., Philadelphia: Saunders, 2007.

90. Mohammadi-Samani S., Jamshidzadeh A., Montaseri H., et al. The effects of some permeability enhancers on the percutaneous absorption of lidocaine. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2010;23:83-88.

91. Simon L.S., Grierson L.M., Naseer Z., et al. Efficacy and safety of topical diclofenac containing dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) compared with those of topical placebo, DMSO vehicle and oral diclofenac for knee osteoarthritis. Pain. 2009;143:238-245.

92. Hegmann K.T., editor. Occupational Medicine Practice Guidelines, 2nd ed. Beverly Farms, Mass: OEM. 2004.

93. Schapowal A., Berger D., Klein P., Suter A. Echinacea/sage or chlorhexidine/lidocaine for treating acute sore throats: A randomized double-blind trial. Eur J Med Res. 2009;14:406-412.

94. Gagnier J.J., van Tulder M.W., Berman B., Bombardier C. Herbal medicine for low back pain: A Cochrane review. Spine. 2007;32:82-92.

95. Beer A.M., Wegener T. Willow bark extract (Salicis cortex) for gonarthrosis and coxarthrosis—results of a cohort study with a control group. Phytomedicine. 2008;15:907-913.

96. Orlowski J.P., Hanhan U.A., Fiallos M.R. Is aspirin a cause of Reye’s syndrome? A case against. Drug Saf. 2002;25(4):225-231.

97. Albrecht M., Nahrsted A., Luepke N.P., et al. Anti-inflammatory activity of flavonol glycosides and salicin derivatives from the leaves of Populus tremuloides. Planta Med. 1990;56:660.

98. von Kruedener S., Schneider W., Elstner E.F. A combination of Populus tremula, Solidago virgaurea and Fraxinus excelsior as an anti-inflammatory and antirheumatic drug. A short review. Arzneimittelforschung. 1995;45:169-171.

99. Vohora S.B., Dandiya P.C. Herbal analgesic drugs. Fitoterapia. 1992;63:195-207.

100. Costello C.H., Butler C.L. An investigation of Piscidia erythrina (Jamaica Dogwood). J Am Pharm Assoc. 1948;37:89-97.

101. Pilcher J.D. The action of certain drugs on the excised uterus of the guinea pig. Arch Intern Med. 1916;18:557.

102. Della Loggia R., et al. Plant flavonoids in biology and medicine II. New York: AR Liss; 1987.

103. Tilgner S. Herbal Medicine from the Heart of the Earth. Creswell, Ore, Wise Acres. 1999.

104. Gregory P.J., Sperry M., Wilson A.F. Dietary supplements for osteoarthritis. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77:177-184.

105. Schoenen J., Jacquy J., Lenaerts M. Effectiveness of high-dose riboflavin in migraine prophylaxis. A randomized controlled trial. Neurology. 1998;50:466-470.

106. Boehnke C., Reuter U., Flach U., et al. High-dose riboflavin treatment is efficacious in migraine prophylaxis: An open study in a tertiary care center. Eur J Neurol. 2004;11:475-477.

107. Ziegler D. Thioctic acid for patients with symptomatic diabetic polyneuropathy: A critical review. Treat Endocrinol. 2004;3:173-189.

108. Magis D., Ambrosini A., Sándor P., et al. A randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial of thioctic acid in migraine prophylaxis. Headache. 2007;47:52-57.

109. Silveri M.M., Parow A.M., Villafuerte R.A., et al. S-adenosyl-L-methionine: Effects on brain energetic status and transverse relaxation time in healthy subjects. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:833-839.

110. Jacobsen S., Danneskiold-Samsøe B., Andersen R. Oral S-adenosyl-methionine in primary fibromyalgia. Double-blind clinical evaluation. Scand J Rheumatol. 1992;20:294-302.

111. Frech T.M., Clegg D.O. The utility of neutraceuticals in the treatment of osteoarthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2007;9:25-30.

112. Vlad S.C., LaValley M.P., McAlindon T.E., Felson D.T. Glucosamine for pain in osteoarthritis: Why do trial results differ? Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:2267-2277.

113. Poolsup N., Suthisisang C., Channark P., Kittikulsuth W. Glucosamine long-term treatment and the progression of knee osteoarthritis: Systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:1080-1087.

114. Clegg D.O., Reda D.J., Harris C.L., et al. Glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, and the two in combination for painful knee osteoarthritis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:795-808.

115. Rozendaal R.M., Koes B.W., van Osch G.J., et al. Effect of glucosamine sulfate on hip osteoarthritis. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:268-277.

116. Black C., Clar C., Henderson R., et al. The clinical effectiveness of glucosamine and chrondroitin supplements in slowing or arresting progression of osteoarthritis in the knee: A systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13(52):1-148.

117. Knudsen J.F., Sokol G.H. Potential glucosamine-warfarin interaction resulting in increased international normalized ratio: Case report and review of the literature and MedWatch database. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28:540-548.

118. Lovett E., Ganta N. Advising patients about herbs and neutraceuticals: Tips for primary care providers. Care. 2010;37:13-30.

119. Wang F., Van Den Eeden S.K., Ackerson L.M., et al. Oral magnesium oxide prophylaxis of frequent migrainous headache in children: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Headache. 2003;43:601-610.

120. Proctor M.L., Murphy P.A. Herbal and dietary therapies for primary and secondary dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (3):2001. CD002124

121. Ambriz-Tututi M., Rocha-González H.I., Cruz S.L., Granados-Soto V. Melatonin: A hormone that modulates pain. Life Sci. 2009;84:489-498.

122. Peres M.F., Masruha M.R., Zukerman E., et al. Potential therapeutic use of melatonin in migraine and other headache disorders. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2006;15:367-375.

123. Vogler B., Rapoport A.M., Tepper S.J., et al. Role of melatonin in the pathophysiology of migraine: Implications for treatment. CNS Drugs. 2006;20:343-350.

124. Borazan H, Tuncer S, Yalcin N, et al. Effects of preoperative oral melatonin medication on postoperative analgesqia, sleep quality and sedation in patients undergoing elective prostatectomy: A randomized clinical trial. J Anesth. 2010;24:155-160.

125. Holick M.F. The vitamin D epidemic and its health consequences. J Nutr. 2005;135:2739S-2748S.

126. Badalian S.S., Rosenbaum P.F. Vitamin D and pelvic floor disorders in women: Results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(4):795-803.

127. Ruiz-Irastorza G., Egurbide M.V., Olivares N., et al. Vitamin D deficiency in systemic lupus erythematosus: prevalence, predictors and clinical consequences. Rheumatology. 2008;47:920-923.

128. Zittermann A. Vitamin D in preventive medicine: are we ignoring the evidence? Br J Nutrition. 2003;89:552-572.

129. Straube S, Andrew Moore R, Derry S, et al. Vitamin D and chronic pain. 2009;141:10-13.

130. Armas LA, Hollis BW, Heaney RP. Vitamin D2 is much less effective than vitamin D3 in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:5387-5391.

131. Vieth R. Vitamin D supplementation, 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations and safety. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:842-856.

132. Kimball S.M., Ursell M.R., O’Connor P., Vieth R. Safety of vitamin D3 in adults with multiple sclerosis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:645-651.

133. Sanders K.M., Stuart A.L., Williamson E.J., et al. Annual high dose oral vitamin D and falls and fractures in older women: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;303:1815-1822.

134. Goldman L., Ausiello D., editors. Goldman Cecil Medicine, 23rd ed., Philadelphia: Saunders, 2008.

135. Lee P., Chen R. Vitamin D as an analgesic for patients with type 2 diabetes and neuropathic pain. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:771-772.

136. Al Faraj S. Al Mutairi K: Vitamin D deficiency and chronic low back pain in Saudi Arabia. Spine. 2003;28:177-179.

137. Lofti A., Abdel-Nasser A.M., Hamdy A., et al. Hypovitaminosis D in female patients with chronic low back pain. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:1895-1901.

138. Cutolo M., Otsa K., Uprus M., et al. Vitamin D in rheumatoid arthritis. Autoimmun Rev. 2007;7:59-64.

139. Mouyis M., Ostor A.J., Crisp A.J., et al. Hypovitaminosis D among rheumatology outpatients in clinical practice. Rheumatology. 2008;47(9):1348-1351.

140. Ahmed W., Khan N., Glueck C.J., et al. Low serum 25 (OH) vitamin D levels (<32 ng/mL) associated with reversible myositis-myalgia in statin-treated patients. Trans Res. 2009;153:11-16.

141. Thys-Jacobs S. Vitamin D and calcium in menstrual migraine. Headache. 1994;34:544-546.

142. Thys-Jacobs S. Alleviation of migraines with therapeutic vitamin D and calcium. Headache. 1994;34:590-592.

143. Pizzorno J.E. The path ahead: What have we learned about vitamin D dosing? Integrative Med. 2010;9:8-12.

144. Jung H.J., Park E.H., Lim C.J. Evaluation of anti-angiogenic, anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive activity of coenzyme Q(10) in experimental animals. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2009;61(10):1391-1395.

145. Hershey A.D., Powers S.W., Vockell A.L., et al. Coenzyme Q10 deficiency and response to supplementation in pediatric and adolescent migraine. Headache. 2007;47(1):73-80.

146. Rozen T.D., Oshinsky M.L., Gebeline C.A., et al. Open label trial of coenzyme Q10 as a migraine preventative. Cephalagia. 2002;22:137-141.

147. Lewis D.W. Pediatric migraine. Neurol Clin. 2009;27(2):481-502.

148. Cordero M.D., De Miguel M., Moreno Fernàndez A.M., et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction and mitophagy activation in blood mononuclear cells of fibromyalgia patients: Implications in the pathogenesis of the disease. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12(1):R17. [Epub ahead of print]

149. D’Andrea G., Bussone G., Allais G., et al. Efficacy of ginkgolide B in the prophylaxis of migraine with aura. Neurol Sci. 2009;Suppl 1:S121-S124.

150. Usai S., Grazzi L., Andrasik F., Bussone G. An innovative approach for migraine prevention in young age: A preliminary study. Neurol Sci. 2010;31(Suppl 1):181-183.

151. Muir A.H., Robb R., McLaren M., et al. The use of Ginkgo biloba in Raynaud’s disease: A double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Vasc Med. 2002;7:265-267.

152. Moher D., Pham B., Ausejo M., et al. Pharmacological management of intermittent claudication: A meta-analysis of randomised trials. Drugs. 2000;59(5):1057-1070.

153. Nicolaï S.P., Kruidenier L.M., Bendermacher B.L., et al. Ginkgo biloba for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;15:CD006888.

154. Somchit M.N., Sulaiman M.R., Zuraini A., et al. Antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of Centella asiatica. Indian J Pharmacol. 2004;36:377-380.

155. De Sanctis M.T., Belcaro G., Incandela L., et al. Treatment of edema and increased capillary filtration in venous hypertension with total triterpenic fraction of Centella asiatica: A clinical, prospective, placebo-controlled, randomized, dose-ranging trial. Angiology. 2001;52(Suppl 2):S55-S59.

156. Hudson T. Women’s encyclopedia of natural medicine, 3rd ed. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2005.

157. Levy R.M., Saikovsky R., Shmidt E., et al. Flavocoxid is as effective as naproxen for managing the signs and symptoms of osteoarthritis in the knee in humans: A short-term randomized, double-blind pilot study. Nutr Res. 2009;29:298-304.

158. Rein E., Kharazmi A., Winther K. A herbal remedy, Herben Vital (stand. powder of a subspecies of Rosa canina fruits), reduces pain and improves general wellbeing in patients with osteoarthritis–a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised trial. Phytomedicine. 2004;11:383-391.

159. Christensen R., Bartels E.M., Altman R.D., et al. Does the hip powder of Rosa canina (rosehip) reduce pain in osteoarthritis patients?—a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Osteoarthr Cartilage. 2008;16:965-972.

160. Liz R., Vigil S.V., Goulart S., et al. The anti-inflammatory modulatory role of Solidago chilensis Meyen in the murine model of the air pouch. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2008;60:515-521.

161. da Silva A.G., de Sousa C.P., Koehler J., et al. Evaluation of an extract of Brazilian arnica (Solidago chilensis Meyen, Asteraceae) in treating lumbago. Phytother Res. 2010;24:283-287.