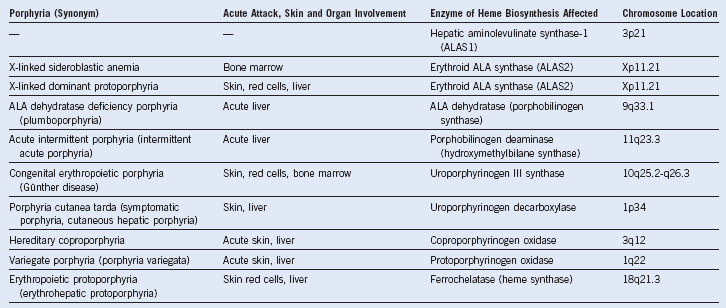

Chapter 10 Heme Biosynthesis and Its Disorders

Porphyrias

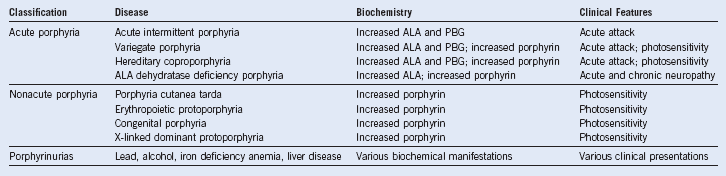

Table 10-1 Porphyrias: Clinical Involvement, Enzymatic Etiology, and Chromosomal Location

ALA, 5-Aminolevulinate.

Measurement of Porphyrins and Precursors

Fluorescence of urine under ultraviolet (UV) light is recommended as the initial screening test for the acute porphyrias,1 whereas plasma fluorescent spectroscopy is the best initial test for diagnosis of cutaneous porphyrias.2 Diverse techniques such as high-pressure liquid chromatography,3 quantitative extraction, and various forms of fluorometry are used to measure porphyrins and precursors.4 The International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine presents diagnostic information on the Internet (www.ifcc.org).

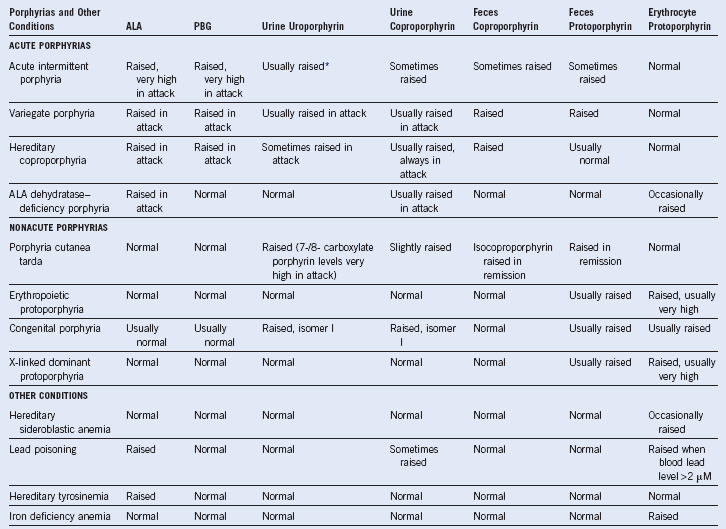

Table 10-3 Changes in Porphyrins and Their Precursors in the Porphyrias, Porphyrinurias, and Hereditary Sideroblastic Anemia

ALA, 5-Aminolevulinic acid; PBG, porphobilinogen.

Precipitating Factors in Acute Porphyria

Hormonal status is also important. Attacks are more common in females, and they rarely occur before puberty or after menopause. Pregnancy and oral contraceptives may also precipitate attacks. Some women experience regular attacks, commencing in the week before the onset of menstruation. These may require luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone (LH-RH) antagonists for control (Table 10-4).

Drugs for Porphyria

Before prescribing any medication to a porphyric patient, advice must be sought from an appropriate specialist. Full drug lists are available on the Internet (www.drugs-porphyria.org). It should be borne in mind that such lists are far from encyclopedic, that new drugs are constantly being introduced to the pharmacopoeia, and that any form of combined preparation must be viewed with suspicion, because little is known about metabolic interactions in these diseases.5 More details of such use and side effects of drugs can be sought from the literature.6

Differential Diagnosis of Acute Intermittent Porphyria

Attacks of acute porphyria must be distinguished from other causes of acute abdominal pain or peripheral neuropathy sometimes associated with psychosis.7 Heavy metal poisoning (i.e., lead or arsenic) and Guillain-Barré syndrome must be considered, as well as paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria with its characteristic early morning hemoglobinuria and abdominal pain.7

A rapid screening test during an acute attack is to mix equal volumes of urine and Ehrlich aldehyde reagent and observe for the pink color of porphobilinogen; alternatively the urine can be left standing in sunlight to observe darkening in color. The differential diagnosis of porphyrias uses qualitative and quantitative measurement of porphyrins and precursors, with subsequent use of enzymatic assay and identification of familial genetic alterations.8

| Drugs | Other Stimuli |

|---|---|

| Alcohol | Fasting or dieting |

| Barbiturates | Hormones, stress |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors | Smoking |

| Anticonvulsants | |

| Antidepressants | |

| Calcium channel blockers | |

| Cephalosporins | |

| Ergot derivatives | |

| Erythromycin | |

| Steroids or anabolic steroids | |

| Contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy | |

| Sulfonamides | |

| Sulfonylureas |

Management of Acute Porphyria

Treatment of Acute Attack

A carbohydrate intake of 1500 to 2000 kcal/24 hr should be maintained throughout the attack to reduce porphyrin synthesis; give this orally or, for more severe attacks, through a fine-bore Teflon nasogastric tube. If this cannot be tolerated, intravenous dextrose (e.g., 20% solution, 2 L/day) should be given. If early in the attack (2 to 4 days from onset), give intravenous hematin as heme arginate (Normosang, Orphan Europe) at 2 to 4 mg/kg over 30 minutes once or twice each day to further reduce the overproduction of porphyrin and precursors.9,10 Hematin (Panhematin, Lundbeck) in similar doses may also be used, although it should be reconstituted in human albumin solution to avoid phlebitis and mild transient prolongation of coagulation times. No renal complications have occurred with the standard recommended dosages, and even patients with renal insufficiency tolerate hematin well, although the dosage should be reduced slightly. The action of heme therapy may be extended by heme oxygenase blockers such as tin protoporphyrin.9 Liver transplantation may be an effective treatment for life-threatening acute intermittent porphyria that fails to respond to medical therapy.11

Prophylaxis

Luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LH-RH) antagonists that suppress ovulation are a valuable form of prophylaxis in menstrually related attacks.12 Estrogens and progestogens such as those in the contraceptive pill must be avoided in acute porphyria. The same applies to most steroids and receptor antagonists such as mifepristone.13

Management of Nonacute Porphyria

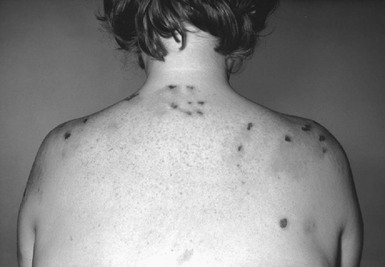

Porphyria Cutanea Tarda

The clinical features are reversed by removing any precipitating agent such as alcohol, halogenated hydrocarbons, and drugs. The patient should be screened for hepatic neoplasm and hepatitis C infection. The mainstay of treatment is to remove liver iron by venesection of 500 mL of blood weekly until clinical remission occurs or until the hemoglobin level falls below 12 g/dL. Chloroquine, at low doses of 125 mg twice per week for several months, has also been helpful because it enhances urinary clearance of porphyrin. When this is not possible, oral cimetidine has been used.14 When venesection is difficult, parenteral and orally active iron chelators can be used to reduce liver iron stores. It is of value to screen the patient and first-degree relatives for hereditary hemochromatosis.

Erythropoietic Protoporphyria

Oral β-carotene offers effective protection in erythropoietic porphyria (EPP) against solar sensitivity. It does so by quenching the radical formation that is a feature of the skin damage. Yellowing of the skin (i.e., carotenemia) is one side effect. Interruption of the enterohepatic protoporphyrin circulation by bile salt–sequestering agents such as cholestyramine reduces plasma protoporphyrin levels and may retard the development of the liver disease. Liver transplantation has been reported to be an effective measure in preventing the progression of this disease.15

Congenital Porphyria

Erythropoiesis should be reduced by means of erythrocyte hypertransfusion and by hematin or heme arginate infusion.16 Bone marrow transplantation has given encouraging biochemical and clinical results, but insufficient numbers of patients have been treated to be certain of the future prospects of this therapy.17 Splenectomy and chloroquine therapy (125 mg twice weekly) have an ameliorating effect, as does hypertransfusion, but life expectancy is usually severely shortened.

Pseudoporphyria and Renal Dialysis

The term pseudoporphyria has been used to describe a bullous dermatosis associated with a number of dermatologic conditions that bear some resemblance to porphyria.18 This photosensitivity is often induced by drugs such as the tetracyclines, naproxen, furosemide, voriconazole, oxaprozin, and many others. In these conditions, there is no alteration in porphyrin metabolism or excretion. It is therefore incorrect to name any of them porphyria; the term pseudoporphyria should not be applied to them, but only to conditions in which alterations of porphyrin metabolism can be found, such as the bullous dermatosis of hemodialysis.19

Patients with renal failure can present with many biochemical features of porphyria before hemodialysis. These abnormalities normalize after dialysis, especially when electrolyte abnormalities such as zinc deficiency are also corrected.20 In a considerable proportion of patients with chronic renal failure, skin changes resembling porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT) develop some months to years after the onset of maintenance hemodialysis. In a minor proportion, genuine PCT can be diagnosed.21 In such cases, there are elevated total porphyrin levels in plasma and in urine if the patient is not anuric. These patients present a therapeutic dilemma because they are normally anemic and unsuitable for phlebotomy therapy.

1 Anderson KE, Bloomer JR, Bonkovsky HL, et al. Recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of the acute porphyrias. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:439.

2 Hindmarsh JT, Oliveras L, Greenway DC. Plasma porphyrins in the porphyrias. Clin Chem. 1999;45:1070.

3 Macours P, Cotton F. Improvement in HPLC separation of porphyrin isomers and application to biochemical diagnosis of porphyrias. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2006;44:1438.

4 Blake D, Poulos V, Rossi R. Diagnosis of porphyria-recommended methods for peripheral laboratories. Clin Biochem Rev. 1992;3:S1.

5 Hift RJ, Meissner PN, Moore MR. Porphyria: A toxicogenetic disease, Vol 14: Medical aspects of porphyrins. Kadish KM, Smith KM, Guilard R, eds. The Porphyrin Handbook. San Diego: Academic Press, 2003.

6 Thunell S, Pomp E, Brun A. Guide to drug porphyrogenicity prediction and drug prescription in the acute porphyrias. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;64:668.

7 Bonkovsky HL, Siao P, Roig Z, et al. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 20-2008. A 57-year-old woman with abdominal pain and weakness after gastric bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2813.

8 Hindmarsh JT, Oliveras L, Greenway DC. Biochemical differentiation of the porphyrias. Clin Biochem. 1999;32:609.

9 Dover SB, Moore MR, Fitzsimmons EJ, et al. Tin protoporphyrin prolongs the biochemical remission produced by heme arginate in acute hepatic porphyria. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:500.

10 Anderson KE, Collins S. Open-label study of hemin for acute porphyria. Clinical practice implications. Am J Med. 2006;119:U19.

11 Dowman JK, Gunson BK, Mirza DF, et al. LT-11-056 liver transplantation for acute intermittent porphyria is complicated by a high rate of hepatic artery thrombosis. Liver Transpl [Epub ahead of print]. 2011. May 26

12 Herrick AL, McColl KE, Wallace AM, et al. LHRH analogue treatment for the prevention of premenstrual attacks of acute porphyria. Q J Med. 1990;75:355.

13 Cable EE, Pepe JA, Donohue SE, et al. Effects of mifepristone (RU-486) on heme metabolism and cytochromes P-450 in cultured chick embryo liver cells, possible implications for acute porphyria. Eur J Biochem. 1994;225:651.

14 Fujita Y, Sato-Matsumura KC. Effective treatment for porphyria cutanea tarda with oral cimetidine. J Dermatol. 2010;37:677.

15 Dowman JK, Gunson BK, Mirza DF, et al. UK experience of liver transplantation for erythropoietic protoporphyria. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2011;34:539.

16 Rank JM, Straka JG, Weiner MK, et al. Hematin therapy in late onset congenital erythropoiekic porphyria. Br J Haematol. 1990;75:617.

17 Tezcan I, Xu W, Gurgey A, et al. Congenital erythropoietic porphyria successfully treated by allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 1998;92:4053.

18 Koszo F, Morvay M, Dobozy A, et al. Erythrocyte uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase activity in 80 unrelated patients with porphyria cutanea tarda. Br J Dermatol. 1992;126:446.

19 Poh-Fitzpatrick MB. Porphyria, pseudoporphyria, pseudopseudoporphyria. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:403.

20 Seubert S, Seubert A, Rumpf K, et al. A porphyria cutanea tarda-like distribution pattern of porphyrins in plasma hemodialysate hemofiltrate in urine of patients on chronic hemodialysis. J Invest Dermatol. 1985;85:107.

21 Guolo M, Stella AM, Melito V, et al. Altered 5-aminolevulinic acid metabolism leading to pseudoporphyria in hemodialysed patients. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1996;28:311.