Chapter 73 Hematology in Aging

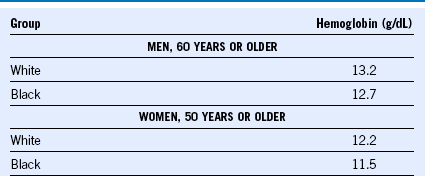

Adapted from Beutler E, Waalen J: The definition of anemia: what is the lower limit of normal of the blood hemoglobin concentration? Blood 107:1747, 2006.

Table 73-2 Hematopoietic Changes Associated With Advancing Age

G-CSF, Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor.

*Guralnik JM, Eisenstaedt RS, Ferrucci L, et al: Prevalence of anemia in persons 65 years and older in the United States: Evidence for a high rate of unexplained anemia. Blood 104:2263, 2004.

Evaluating Anemia in Older Adults

To define anemia, we follow the hemoglobin criteria defined by Beutler and Waalen in Table 73-1. However, hemoglobin trajectory over time is as important. Based on the fact that the average hemoglobin level declines in older adults about 1 g/dL over 15 years or more, we consider decline of 1 g/dL in less than 5 years or 2 g/dL over 10 years significant and supports a complete evaluation. We work diligently to retrieve remote blood counts. Older adults frequently have had blood counts obtained either routinely in the past, before a procedure, or at the time of hospital admission. Counts at the time of hospital admission may be the least reliable because they occur in the context of an illness.

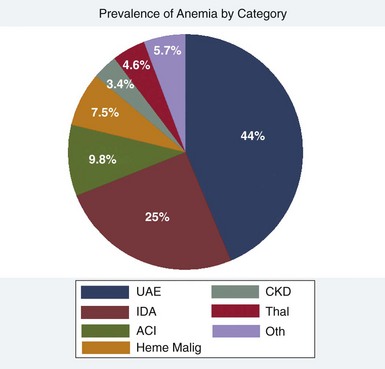

Figure 73-1 CATEGORIZATION OF PRIMARY ANEMIA ETIOLOGY OR UNEXPLAINED ANEMIA IN THE ELDERLY (UAE) IS SHOWN.

(From Artz AS, Thirman MF: Unexplained anemia predominates despite an intensive evaluation in a racially diverse cohort of older adults from a referral anemia clinic. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 66:925, 2011.)

Table 73-3 Differential Diagnosis for Common Causes of Cytopenias in Older Adults