89 Hand and Wrist Injuries

Epidemiology

Annually, more than 16 million people suffer some form of hand injury, and more than 4.8 million will seek treatment of these injuries at the emergency department (ED).1 Traumatic injuries may include lacerations, fractures, and tendon or ligamentous injuries. Most injuries are readily identified in the ED, provided that the assessment is effective.2 Because the morbidity associated with undiagnosed, misdiagnosed, or mistreated hand injuries is significant, a high level of expertise is required of the EP.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

During the history the patient’s hand dominance and career should also be ascertained and documented. Factors that may compromise wound healing, such as smoking, drug use, or an immunocompromised state, are important to document.2 Tetanus status should be verified.

Despite its complicated nature, the hand can be examined adequately in a short period. Developing a rapid, reproducible hand examination strategy and performing it regularly will decrease the chance of missing subtle injuries. Even when a specific injury is obvious, it is important to examine the entire hand to avoid overlooking less obvious, coincident injuries. Box 89.1 lists one approach to comprehensive assessment of the hand.

Box 89.1 Two-Minute Hand Examination

Ligamentous

Flexor digitorum profundus tendon—hold the proximal interphalangeal joint in extension; flex the distal interphalangeal joint against resistance

Flexor digitorum sublimis tendon—hold the metacarpophalangeal joint in extension; flex the proximal interphalangeal joint against resistance

Extensor tendons—place the hand palm down; extend the digit with resistance at the nail bed

Ulnar collateral ligament—adduct the thumb against resistance

Assuming that no active bleeding is occurring and requires immediate attention, examination of the hand begins with inspection. All rings, watches, and other potentially constricting devices should be removed immediately.3 Lacerations and other disruptions in skin integrity are usually recognized easily; erythema, soft tissue swelling, and ecchymoses should also be noted. It is important to compare the general position of the hand with that of the unaffected side inasmuch as many fractures or tendon disruptions will cause characteristic deformities that are recognizable on inspection.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

Fractures of the Hand

Metacarpal Bone Fractures

Metacarpal base fractures are uncommon and usually of little significance.2 The exception is at the base of the fifth metacarpal bone, where there can be associated subluxation of the metacarpal-hamate joint. The injured hand should be immobilized in an ulnar gutter splint and scheduled for referral to hand surgery.

Bennett/Reverse Bennett and Rolando Fractures

A Bennett fracture is a fracture of the proximal first metacarpal bone (Fig. 89.1). The classic mechanism is an axial load onto a flexed and adducted thumb. For example, a football quarterback strikes the helmet of an opposing player after releasing a throw. In this avulsion injury, the strong abductor pollicis longus muscle fractures the bone at the point of its insertion at the ulnar aspect of the first metacarpal bone. This causes displacement of a bony fragment, which can be seen on a plain film radiograph. It is usually an unstable fracture, and ED management should consist of referral to a hand surgeon and immobilization in a thumb spica splint. Potential long-term morbidity includes malunion, decreased function, and significant arthritis.

Boxer’s Fracture

Although many people refer to any fracture of the fifth metacarpal as a boxer’s fracture, the specific injury is a fracture through the neck of the bone (Fig. 89.2). This injury is most frequently seen when a solid object is forcefully struck with a closed fist. True boxer’s fractures may carry significant morbidity because in addition to being an unstable fracture, the injury often has a rotational component. If allowed to heal in this position, the hand will be deformed and weakened.

Distal Phalanx Fractures

The most common distal phalanx fracture is a tuft fracture, and nail bed injuries are the most common complication of this fracture.2 There is some controversy regarding the need to repair nail bed injuries; however, most authors recommend performing trephination only for nail bed hematomas involving 30% to 50% or greater of the nail bed surface. When the nail bed is involved, tuft fractures are considered open fractures. Although some physicians prescribe antibiotics empirically, evidence suggests that prophylactic antibiotics are not indicated.4 Proximal distal phalanx fractures are often unstable and require hand surgeon referral for percutaneous wire placement. An attempt to reduce any rotational deformity or angulation should be made before splinting. Splinting should isolate the DIP joint alone.

Ligamentous Injuries of the Hand

Gamekeeper’s/Skier’s Thumb

Gamekeeper’s thumb is also called skier’s thumb. The mechanism is hyperextension of an abducted thumb causing injury to the ulnar collateral ligament, and it is often associated with an avulsion fracture (Fig. 89.3). Historically, old-world gamekeepers sustained this injury while dispatching wounded birds during hunts. Today, this injury often occurs when a skier falls while grasping the ski pole.

Fig. 89.3 Gamekeeper’s thumb (arrow).

(From Perron AD, Brady WJ. Evaluation and management of the high-risk orthopedic emergency. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2003;21:159–204.)

Physical examination will be remarkable for tenderness at the ulnar collateral ligament, laxity at the MCP joint, and inability to actively oppose the thumb (Fig. 89.4). Most ulnar collateral ligament ruptures occur at the distal attachment. If the injured joint demonstrates 40 degrees of radial angulation during stressing, complete ligament rupture should be assumed. An associated avulsion fracture may be present. Treatment consists of immobilization in a thumb spica splint, NSAIDs, and referral to a hand surgeon for open reduction with internal fixation.

Jersey Finger

Jersey finger is an injury often associated with tackling sports (Fig. 89.5). The injury itself consists of disruption of the flexor digitorum profundus joint, which is responsible for flexion of the digit at the DIP joint. It occurs when a digit (often the second digit) is forced into extension while actively being flexed, as might occur when grabbing an opponent’s jersey during a tackle.

Mallet Finger

Mallet finger is in many ways the functional opposite of jersey finger. In mallet finger the distal extensor tendon is ruptured (Fig. 89.6). It often occurs when the distal phalanx of a finger (or thumb) is forced into flexion while being actively extended. In sports the middle finger is most often affected because of its length, and it occurs when the finger is jammed, as when attempting to catch a ball.

Extensor Tendon Injuries

Open wounds on the dorsum of the hand and digits should trigger suspicion for extensor tendon injury. The Verdan extensor tendon injury classification system uses eight anatomic zones to direct treatment (Table 89.1).

Table 89.1 Verdan Classification of Extensor Tendon Injuries with Appropriate Disposition

| ZONE | ANATOMIC LOCATION | DISPOSITION |

|---|---|---|

| I | Distal phalanx to distal interphalangeal joint | Splint, hand surgeon referral |

| II | Middle phalanx | Splint, hand surgeon referral |

| III | Proximal interphalangeal joint | Splint, hand surgeon referral |

| IV | Proximal phalanx | ED primary repair, splint |

| V | Metacarpophalangeal joint | Splint, hand surgeon referral |

| VI | Dorsum of the hand/metacarpals | ED primary repair, splint |

| VII | Dorsum of the wrist, carpals | Hand surgeon primary repair |

| VIII | Distal forearm, proximal wrist | Hand surgeon primary repair |

ED, Emergency department.

Data from Verdan CE. Primary and secondary repair of flexor and extensor tendon injuries. In: Flynn JE, editor. Hand surgery. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1975.

Flexor Tendon Injuries

All patients with open flexor tendon injuries should be referred to a hand surgeon for emergency evaluation (Table 89.2). However, some knowledge of the nomenclature and prognoses associated with flexor tendon injuries will aid the EP in conversations with both the consultant and the patient.

Table 89.2 Verdan Classification of Flexor Tendon Injuries with Appropriate Disposition

| ZONE | ANATOMIC LOCATION | DISPOSITION |

|---|---|---|

| I | Distal to insertion of the flexor digitorum sublimis tendon | Hand surgeon primary repair |

| II | Area of the flexor sheath with both the flexor digitorum sublimis and flexor digitorum profundus tendons | Hand surgeon primary repair |

| III | Carpal tunnel to the proximal aspect of the flexor sheath | Hand surgeon primary repair |

| IV | Carpal tunnel | Hand surgeon primary repair |

| V | Forearm proximal to the carpal tunnel | Hand surgeon primary repair |

Data from Verdan CE. Primary and secondary repair of flexor and extensor tendon injuries. In: Flynn JE, editor. Hand surgery. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1975.

Repair of complete lacerations within 24 hours is most commonly recommended. Operative repair is usually limited to injuries involving greater than 50% of a cross-sectional area. Injuries involving less than 50% are frequently treated conservatively with splinting. Newer data suggest that conservative management is adequate for injuries occupying less than 75% of a cross-sectional area; however, this decision should be deferred to the consulting hand surgeon.1 When splinting flexor tendon injuries, the wrist should be placed in 30 degrees of flexion, MCP joint injuries in 70 degrees of flexion, and DIP or PIP joint injuries in 10 degrees of flexion. Classification of flexor tendon injuries is based on anatomic location, treatment, and prognosis. All patients with flexor tendon injuries should be referred to a hand surgeon for operative exploration and repair.

Fractures of the Wrist

Scaphoid Fractures

Morbidity is high with this injury because the bone is anatomically predisposed to avascular necrosis and nonunion. The blood supply to the scaphoid originates from the radial and palmar arteries and flows from distal to proximal. The most proximal aspect of the scaphoid receives blood only from this distal to proximal flow, and if this flow is interrupted by a fracture, the risk for avascular necrosis and nonunion is high. For this reason all patients with a traumatic mechanism and scaphoid tenderness, as assessed by palpation of the anatomic snuffbox or pain with axial loading of the thumb, should be treated with a thumb spica splint and referred for follow-up. Roughly 15% of these patients will have a scaphoid fracture despite unrevealing plain films.5

Dislocations of the Wrist

Scapholunate, perilunate, and lunate dislocations are varying degrees of the same disease process. The mechanism is one of hyperextension. In cadaver work it was shown that progressive force applied to the wrist in a hyperextension mechanism will reliably re-create these injuries in a persistent pattern.6 The reason is anatomically based and the result of progressive ligament injuries.

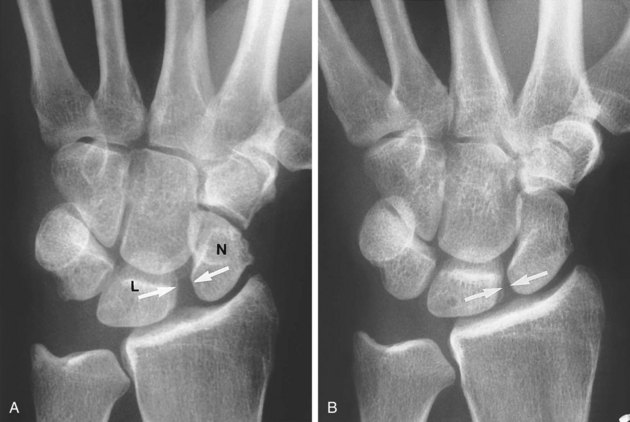

Scapholunate Dislocation

Scapholunate dislocation is the most common of these injuries and occurs with the least amount of force. It can be diagnosed on plain film radiography. Scapholunate dislocation results in a classic radiologic finding—the Terry-Thomas sign (Fig 89.7). Terry-Thomas was a 20th-century British comedian who possessed a noticeable gap between his two front teeth, reminiscent of the wide space (2 mm when measured on an anteroposterior view) seen between the scaphoid and lunate bones when they are dislocated.3 Stress views accentuate this finding. Additionally, the scaphoid may twist on its axis and cause a ringlike shadow known as the signet ring sign. This artifact is caused by the x-rays traveling longitudinally down the twisted scaphoid, unlike the normal crosswise orientation. Mayfield et al. classified this injury as a stage I injury.6

Perilunate Dislocation

Stage II injury is associated with progressively more force (e.g., an automobile accident versus a slip and fall) and results in perilunate dislocation (Fig. 89.8). Perilunate dislocations may be a difficult concept because there is no “perilunate” bone. Perilunate dislocation is a disruption of the ligamentous structures around (“peri”) the lunate bone. One of these structures is the capitate, which most often dislocates dorsally. Perilunate dislocation may perhaps better be called capitate dislocation; however, perilunate dislocation is actually a more accurate description of the stepwise disease process as outlined by Mayfield et al.6 Dislocation of the capitate can be associated with a scaphoid fracture. The EP should be diligent in assessing for one in the setting of the other. Perilunate dislocation is frequently overlooked despite the classic plain film finding of the capitate and the remainder of the distal part of the hand lying dorsal to the lunate on the lateral projection.

Lunate Dislocation

The result is a distal radius and capitate pseudoarticulation, with the lunate lying palmar to the “new” wrist articulation. This is best viewed on a lateral plain film projection and causes the “spilled teacup” sign (Fig. 89.9). When teaching this concept, the author has asked students to imagine a watermelon seed being squeezed between two fingers and then popping forward with force. This is essentially what happens to the lunate as it is “squeezed” by the radius and distal wrist structures, including the capitate, in an extreme hyperextension mechanism. Lunate dislocation often compresses the carpal tunnel and can cause median neuropathy.

Bites to the Hand

Because of the potential for injury and morbidity, all open injuries of the MCP joint should be treated as closed-fist bite wounds, or “fight bites,” until proved otherwise. These often minor-appearing injuries are by definition caused by a clenched fist versus human teeth and are well known for poor outcomes. Potential complications include violation of the joint capsule, extensor tendon injury, and contamination of the deep fascial space.7 The potential for infection is great because of the poor vascular supply of the extensor tendon and joint capsule. Treatment of these injuries is threefold: surgical decontamination, antibiotics, and dynamic splinting.8 These injuries are not limited to fist fights and also commonly occur during sporting events.5

Delayed manifestations most commonly occur 2 to 3 days after the inciting event and consist of signs and symptoms of local or significantly advanced infection. Any indication of infection or joint space or tendon sheath involvement should prompt referral to a hand surgeon for irrigation and débridement. The timing of initiation of intravenous antibiotics should be determined in consultation with the hand surgeon, who may wish to delay antibiotic treatment until after tissue for culture has been obtained intraoperatively. Antimicrobial therapy should cover common pathogens found in the human oral and skin flora, including aerobic and anaerobic pathogens. Staphylococcus aureus is the most common pathogen, followed by Streptococcus species, Corynebacterium species, and Eikenella corrodens.9

Prophylactic antibiotics for clenched-fist bite wounds should be initiated for all but the most superficial injuries. Recommended regimens include amoxicillin–clavulanic acid, a combination of penicillin and dicloxacillin, and a combination of penicillin and a first-generation cephalosporin.9

High-Pressure Injection Injuries

High-pressure injection injuries occur when substances such as paint, oil, grease, solvents, and water are sprayed under high pressure. These substances can penetrate deeply into the soft tissues of the hand and cause inflammation, infection, fibrosis, and severe disability. In one series the rate of amputation approximated 50%, and when patients are initially seen more than 6 hours after the injury, amputations are the rule rather than the exception.10,11 Even a small puncture wound with a history of high-pressure injection should be considered a high-priority emergency.

Treatment

Anesthesia and Analgesia

The hand is densely innervated to increase tactile discrimination and complex function. Accordingly, hand injuries can be very painful. The decision to manage an injury by infiltration of a local anesthetic, a regional anesthetic technique, oral or parenteral analgesics, or a combination of these approaches will vary. It is worth noting that the hand is highly amenable to regional anesthetic techniques that can be mastered quickly by EPs with a bit of practice. Local and regional anesthesia is discussed in Chapter 10. A number of instructional websites also provide detailed information on these techniques, including a site developed at our institution (see www.mmc.org/em_body.cfm?id=3235).

Treatment of Open Wounds

Unless a plan for intraoperative washout is in place, all open hand and wrist injuries should undergo meticulous irrigation. When performing irrigation, a 60-mL syringe and an 18-gauge angiocatheter or splashguard device will generate the proper irrigation pressure. No study has shown any benefit of wound soaking or the use of antiseptic solution during irrigation. Tap water irrigation has proved to be as safe as irrigation with sterile solutions.6 As a rule, patients with all but the most minor hand injuries should receive prophylactic antibiotics.

Follow-Up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

![]() Red Flags

Red Flags

Cautions for Physicians

Do not cut corners during physical examination of the hand. This will invariably lead to misdiagnosis, mistreatment, and loss of function.

All lacerations involving the extensor surface of the hand are “fight bites” until proved otherwise. Never accept the history at face value when the injury pattern is suspicious.

In patients with a history of high-pressure injection injuries, do not be fooled by a seemingly innocuous skin puncture wound.

Failure to immobilize, failure to consult, and failure to arrange timely follow-up are common avoidable pitfalls in the management of hand and wrist injuries.

![]() Documentation

Documentation

Hand dominance, the profession of the patient, and the timing and mechanism of injury are essential elements of the history in patients with hand and wrist injuries.

“Neurovascular intact” is not enough for a hand injury! Documentation should carefully reflect assessment of the pulses and capillary refill. Motor and sensory function of the median, radial, and ulnar nerves should be individually tested and documented.

Because follow-up is such a crucial element in the management of hand and wrist injuries, documentation of phone consultation and agreed-on decisions for definitive management should be explicitly documented.

Tips and Tricks

Regional anesthesia of the median, radial, and ulnar nerves can easily be mastered. These techniques improve the patient’s comfort and the physician’s ability to assess and manage injury.

Use plain radiography to assess for air or radiopaque material in patients suffering high-pressure injection injuries.

Amadio P. What’s new in hand surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:468–473.

Harrison B, Holland P. Diagnosis and management of hand injuries in the emergency department. Emerg Med Pract. 2005;7:1–28.

Hogan CJ, Ruland RT. High-pressure injection injuries of the upper extremity: a review of the literature. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20:503–511.

Perron AD, Miller MD, Brady WJ. Orthopedic pitfalls in the ED: fight bite. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20:114–117.

Southall JC, Sanders SP. Adult hand trauma. Trauma Rep. 2006;7(5):1–12.

1 Amadio P. What’s new in hand surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:468–473.

2 Chung KC, Spilson SV. The frequency and epidemiology of hand and forearm fractures in the United States. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2001;26:908–915.

3 Harrison B, Holland P. Diagnosis and management of hand injuries in the ED. Emerg. Med Pract. 2005;7:1–28.

4 Sukop A, Kufa R. [Primary surgical treatment of amputated fingers and indications for digital replantation.]. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Czech. 2005;72:129–133.

5 Wackerle JF. A prospective study identifying the sensitivity of radiographic findings and the efficacy of clinical findings in carpal navicular fractures. Ann Emerg Med. 1987;16:733–737.

6 Mayfield JK, Johnson RP, Kilcoyne RK. Carpal dislocations: pathomechanics and progressive perilunar instability. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1980;5:226–241.

7 Perron AD, Miller MD, Brady WJ. Orthopedic pitfalls in the ED: fight bite. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20:114–117.

8 Bunzli WF, Wright DH, Hoang AT, et al. Current management of human bites. Pharmacotherapy. 1998;18:227–234.

9 Medeiros L, Saconato H. Antibiotic prophylaxis for mammalian bites. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2, 2003. CD001738

10 Pinto MR, Turkula-Pinto LD, Cooney WP, et al. High-pressure injection injuries of the hand: review of 25 patients managed by open wound technique. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1993;18:125–130.

11 Luber KT, Rehm JP, Freeland AE. High-pressure injection injuries of the hand. Orthopedics. 2005;28:129–132.