124 Gynecologic Pain and Vaginal Bleeding

• The possibility of pregnancy should be considered in every patient with a chief complaint of vaginal bleeding or pelvic pain.

• Ectopic pregnancy, acute appendicitis, and ovarian torsion must be considered in female patients with acute pelvic pain.

• Up to 50% of patients with ovarian torsion have normal findings on ultrasound.

• Malignancy should be considered in postmenopausal women with new-onset vaginal bleeding.

• With the exception of physiologic withdrawal bleeding in the neonate, vaginal bleeding in a prepubescent girl is always abnormal.

Vaginal Bleeding

Epidemiology

Dysfunctional Uterine Bleeding

DUB affects an estimated 30% of women in the United States, is most common at the extremes of the reproductive years, and has no predilection for race. DUB rarely causes mortality but is accountable for two thirds of all hysterectomies and the majority of endoscopic endometrial destructive surgery.1

Uterine Leiomyomas (Fibroids)

Uterine leiomyomas (fibroids) are the most common pelvic tumor in women and have been noted on pathologic examination in approximately 80% of surgically excised uteri.2 Risk factors include African American race, early menarche (<10 years of age), nulliparity, and family history. Several studies have shown more subtle correlations with obesity and diet.3,4

Endometrial Cancer

Endometrial cancer is the fourth most common cancer in women and occurs in approximately 25 per 100,000 women.5,6 This malignant disease develops during the reproductive and menopausal years, with most patients being 50 to 59 years of age. About 5% of women younger than 40 have adenocarcinoma, and it is diagnosed in a quarter of patients before menopause. Many cases of endometrial cancer go undetected given that Papanicolaou smears detect only 50% of cases and the diagnosis is rarely considered in perimenopausal women despite the aforementioned statistics.

Cervical Cancer

Cervical cancer is the second most common malignancy in women worldwide. Approximately 11,000 new cases are diagnosed annually in the United States, and it accounts for around 4000 deaths per year. Minority populations are more commonly affected. The peak incidence of cervical cancer occurs in women 45 to 54 years of age; however, there is a surge in prevalence in women in their 20s and 30s as human papillomavirus (HPV) rates have increased.5,6

Pathophysiology

Common terminology and definitions for vaginal bleeding are listed in Box 124.1. An understanding of the normal female reproductive cycle is useful when caring for patients with vaginal bleeding and pelvic pain. The normal reproductive cycle is 28 days, with a range of 21 to 35 days, and the average age at menarche is approximately 12.5 years. The complex hormonal feedback mechanism that governs the female reproductive cycle is controlled by the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis. Days 1 to 14 are known as the follicular or proliferative phase and are dominated by the release of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus; GnRH in turn stimulates pituitary release of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). During this phase a dominant ovarian follicle matures and produces estrogen, which causes the endometrium to thicken and prepare for possible embryo implantation. Positive feedback of estrogen to the pituitary gland induces a surge in luteinizing hormone (LH) on day 14 of the cycle, which results in ovulation. Days 14 to 28 are known as the luteal or secretory phase; this phase is predominated by progesterone production from the corpus luteum, which induces maturation of the endometrium. If conception and implantation do not occur, the corpus luteum involutes, estrogen and progesterone levels fall, and menstruation occurs.

Disruption at any point in this feedback loop may cause pelvic pain or abnormal vaginal bleeding.

Dysfunctional Uterine Bleeding

DUB is the most common cause of menorrhagia in menstruating females and is defined as abnormal uterine bleeding in the absence of organic disease. DUB can be ovulatory or anovulatory. Ovulatory DUB is hallmarked by regular intervals of increased menstrual flow. The root cause is an abnormality in uterine hemostasis secondary to cytokine and prostaglandin production. More commonly (accounting for 90% of cases of DUB), anovulatory DUB is hallmarked by irregular intervals of alternating heavy and light flow. This can be caused by primary ovarian disorders or a disruption in the HPO axis.7

Uterine Leiomyomas (Fibroids)

The disease process just described generally occurs in the fourth decade of life and usually abates after menopause. Approximately 10% to 40% of fibroids will regress over a period of 6 months to 3 years, and almost all symptomatology will abate at the time of menopause because these uterine tumors are estrogen sensitive. With the use of postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy, however, symptoms may continue past the cessation of menses.8,9

Cervical Cancer

Risk factors for cervical cancer are strongly correlated with sexual activity and include multiple sexual partners, early age at first coitus, early pregnancy, and previous history of sexually transmitted diseases. All these risk factors increase exposure to HPVs, which have been implicated as a major risk factor for the development of cervical cancer and high-risk lesions.10

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

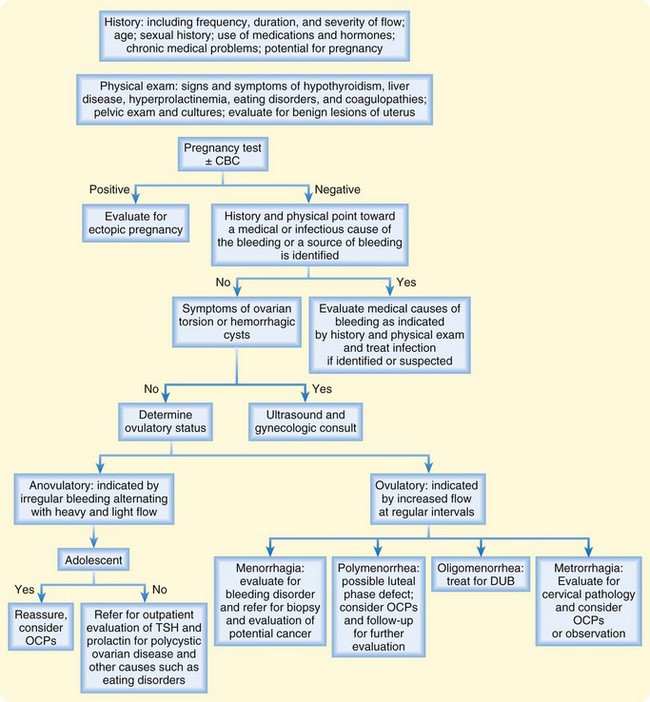

The most common causes of abnormal vaginal bleeding in nonpregnant patients are DUB and uterine leiomyomas. Tables 124.1 and 124.2 list the differential diagnosis of vaginal bleeding in nonpregnant females. Figure 124.1 details an approach to patients seen in the emergency department (ED) with the complaint of vaginal bleeding.

| TERMINOLOGY | DEFINITION |

|---|---|

| Amenorrhea | Cessation of menses for >6 mo |

| Dysmenorrhea | Pain associated with menses |

| Hypomenorrhea | Menstrual volumes < 20 mL/cycle |

| Menorrhagia | Menses > 80 mL/cycle or occurring for >7 days |

| Metrorrhagia | Vaginal bleeding between menstrual cycles or irregular cycles |

| Menometrorrhagia | Prolonged or heavy bleeding at irregular intervals |

| Oligomenorrhea | Decreased frequency of cycles (>35 days per cycle) |

| Polymenorrhea | Increased frequency of cycles (<21 days per cycle) |

| Postmenopausal bleeding | Bleeding 6-12 mo after menopause |

Table 124.2 Systemic Causes of Abnormal Vaginal Bleeding

| CAUSE | MECHANISM |

|---|---|

| Weight loss Stress Excessive exercise |

Hypothalamic suppression of GnRH |

| Polycystic ovarian disease | Excessive estrogen effects on the endometrium Anovulatory cycles |

| Hypothyroidism | Anovulatory cycles |

| Hyperthyroidism | Changes in androgen and estrogen production |

| Hyperprolactinemia (prolactinoma) | Mass effect on the pituitary stalk reduces GnRH secretion |

| Liver failure | Decreased production of vitamin K–dependent clotting factors Increased estrogen levels secondary to decreased metabolism |

| Renal failure | Inherent platelet dysfunction |

Decreased LH, FSH function

FSH, Follicle-stimulating hormone; GnRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone; LH, luteinizing hormone.

Fig. 124.1 Algorithm outlining an approach to patients with abnormal vaginal bleeding.

CBC, Complete blood count; OCPs, oral contraceptive pills; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone.

Uterine Leiomyomas (Fibroids)

Transvaginal ultrasound remains the primary imaging modality in this patient population. This study has high sensitivity (95% to 100%) for detecting myomas in mild to moderate cases of uterine enlargement. Other imaging modalities include diagnostic hysteroscopy, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and hysterosalpingography.11

Treatment

Uterine Leiomyomas (Fibroids)

Treatment of leiomyomas is generally initiated when the tumors become symptomatic and is dependent on size, location, severity, age, and reproductive plans. OCPs again are the first-line treatment for medical management; however, although they may work well in regulating abnormal uterine bleeding, they are not very effective in reducing the bulk symptoms. More effective at medical management of fibroids are GnRH agonists. They work by causing an increase in the release of gonadotropins, which in turn desensitizes and downregulates the reproductive tissue and thus causes a hypogonadal state.12,13 Most women will experience amenorrhea and a significant reduction (35% to 60%) in uterine size within 3 months of initiation of therapy. Even though these medications are quite effective, initiation of therapy should be guided by a gynecologist, and they are rarely started in the ED setting. The addition of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is useful in this population to regulate painful menses, but they do not have much action on uterine bleeding.

Pelvic Pain

Epidemiology

Ovarian Torsion

Ovarian torsion is the fifth most common gynecologic surgical emergency, and because of vague, nonspecific findings, the diagnosis is usually delayed, which can result in necrosis of the ovary and poor salvage rates.14 Several studies have reported salvage rates as low as 10% to 25%. Adnexal torsion can occur at any age, but the highest incidence is in the early reproductive years, with approximately 80% of cases occurring in those younger than 50 years.

Ovarian Tumors

Ovarian cancer is the most common cause of death from gynecologic tumors in the United States. Worldwide, the reported lifetime risk for the development of ovarian malignancy is 1 in 70, and it accounts for 100,000 deaths annually.15 Ovarian cancer affects white women more than black women, and the incidence increases with age. The mean age of females with ovarian carcinoma is 56. The overall prognosis for ovarian cancer is poor, with reported 5-year mortality rates reaching 46%, but it is closely related to staging. In girls younger than 9 years, 80% of ovarian masses are malignant, with the majority being germ cell tumors. These tumors are generally localized to the ovary and have cure rates of 90% after chemotherapy.

Endometriosis

Endometriosis is commonly a disease of reproductive-age women, with the highest incidence of disease in those 25 to 35 years of age. It is uncommon in prepuberal girls and postmenopausal women who are not receiving estrogen replacement therapy. The disease is reported to occur in approximately 7% to 10% of the general population of women and is found in 20% to 50% of infertile women and 80% of women with chronic pelvic pain. There is a strong familial relationship, with the incidence in women who have an affected first-degree relative being significantly increased.16,17

Pathophysiology

Ovarian Tumors

Epithelial tumors represent the most common histologic type (90%), with other causes including sex cord stromal tumors, germ cell tumors, and metastatic disease. These tumors appear as partially cystic lesions with solid components.18 Metastatic disease is often found on the peritoneal surfaces but can be found in the liver, small bowel, uterus, lymphatic system, and lungs. In the prepubescent population, germ cell tumors are the most common histologic type, and the risk for teratomas increases into adolescence.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

The differential diagnosis of pelvic pain in women is quite extensive and includes disease processes in the gastrointestinal, urinary, and reproductive systems (Box 124.2). Careful consideration should always be given to the possibility of acute appendicitis and ovarian torsion in a nonpregnant female with pelvic pain.

Box 124.2 Differential Diagnosis of Pelvic Pain in Nonpregnant Females

Ovarian Torsion

The clinical diagnosis of ovarian torsion is based on findings on physical examination and clinical suspicion, in coordination with pelvic imaging; however, definitive diagnosis is based on surgical findings.19,20 Pelvic ultrasound is the first-line diagnostic imaging modality used to aid in identification of ovarian torsion. Doppler ultrasound can be used to identify the physical anatomy of the pelvic organs, as well as to detect ovarian vessel flow. Data on the sensitivity of Doppler ultrasound in detecting ovarian torsion are controversial, especially with regard to vessel flow. Sensitivities as low as 43% and as high as 100% have been reported. In contrast, Doppler ultrasound is quite specific for diagnosing torsion, with sensitivities found to be anywhere from 92% to 97%.21 It has been reported that up to 50% of patients with torsion may have normal findings on pelvic ultrasound. Therefore, despite negative findings on imaging, if the EP has high enough suspicion for ovarian torsion, prompt gynecologic consultation is warranted. CT and MRI have also been shown to aid in the diagnosis, but their cost and the time required for imaging are prohibitive to regular use of these imaging modalities as long as ultrasound is readily available.

Laboratory testing is generally performed in the setting of acute abdominal pain. Changes in the white blood cell count, hematocrit, and electrolytes have been seen with torsion but are quite nonspecific. Research to identify serum markers is promising, with several studies reporting that increased levels of interleukin-6 are associated with ovarian torsion; however, further investigation is warranted.22,23

Ovarian Tumors

Many laboratory tests and serum markers can be used to evaluate an ovarian mass; however, much of the work-up is done on an outpatient basis and is guided by a gynecologist. The laboratory testing done by an EP is usually limited to evaluation of pelvic pain in conjunction with vomiting. Further laboratory testing will probably include serum markers such as CA 125, which can be elevated in 80% of women with ovarian malignancy and is 90% sensitive in women with advanced disease. However, given that it has low sensitivity in women with early disease and can be associated with several other gynecologic and nongynecologic illnesses, routine testing in the regular population is discouraged.24,25 Promising studies of human epididymal secretory protein E4 have been shown to be more specific for ovarian carcinoma, but further investigation is warranted.

Treatment

Ovarian Torsion

Management of ovarian torsion is emergency operative intervention in an attempt at detorsion of the affected adnexal structures and restoration of blood flow and venous drainage. In the past the adnexal structures were surgically resected; however, recent studies and practice have shown that mechanical detorsion is effective and safe. The most important factor in preservation of ovarian function is early recognition and treatment. Several studies have reported high salvage rates when treatment is initiated within the first 24 hours of the onset of symptoms.20,26

Follow-Up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

Tips and Tricks

Assume that all women of childbearing age are pregnant until proved otherwise.

In patients with strong suspicion for ovarian torsion despite negative ultrasound findings, prompt gynecologic evaluation is warranted.

About 20% to 25% of cases of endometrial cancer occur before menopause; any patient without a definitive cause of the vaginal bleeding should be referred to a gynecologist for endometrial evaluation.

![]() Documentation

Documentation

Bedside pregnancy test results

Onset and duration of symptoms

Duration and frequency of past menstrual cycles

Complete sexual history, including contraception methods, number of partners, history of sexually transmitted diseases

History of previous abnormal Papanicolaou smears

Associated symptoms, including fever, breast changes, anorexia, weight changes, hirsutism, bowel or bladder changes

Berger K. Ovarian cyst/torsion. In: Rosen & Barkin’s 5-minute emergency medicine consult. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007.

Schorge J, et al. Williams gynecology. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008.

Valentine C. Vaginal bleeding. In: Rosen & Barkin’s 5-minute emergency medicine consult. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007.

1 Pitkin J. Dysfunctional uterine bleeding. BMJ. 2007;334:1110–1111.

2 Buttram VC, Jr., Reiter RC. Uterine leiomyomata: etiology, symptomatology, and management. Fertil Steril. 1981;36:433–445.

3 Cramer SF, Patel A. The frequency of uterine leiomyomas. Am J Clin Pathol. 1990;94:435–438.

4 Marshall LM, Spiegelman D, Barbieri RL, et al. Variation in the incidence of uterine leiomyoma among pre-menopausal women by age and race. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:967–973.

5 Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. SEER Database: incidence—SEER 9 Regs Public-Use. National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program. Available at http://seer.cancer.gov/

6 Henley SJ, King JB, German RR, et al. Surveillance of screening-detected cancers (colon and rectum, breast, and cervix)—United States, 2004–2006. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2010;59(9):1–25.

7 Tibbles CD. Selected gynecologic disorders. 7th ed. Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, et al, eds. Rosen’s emergency medicine: concepts and clinical practice. St Louis: Mosby; 2009;vol. 1.

8 Peddada SD, Laughlin SK, Miner K, et al. Growth of uterine leiomyomata among premenopausal black and white women. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19887–19892.

9 DeWaay DJ, Syrop CH, Nygaard IE, et al. Natural history of uterine polyps and leiomyomata. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:3–7.

10 Schiffman MH, Bauer HM, Hoover RN. Epidemiologic evidence showing that human papillomavirus infection causes most cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:958–964.

11 Dueholm M, Lundorf E, Hansen ES, et al. Accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging and transvaginal ultrasonography in the diagnosis, mapping, and measurement of uterine myomas. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:409–415.

12 Friedman AJ, Barbieri RL, Doubilet PM, et al. A randomized, double-blind trial of a gonadotropin releasing–hormone agonist (leuprolide) with or without medroxyprogesterone acetate in the treatment of leiomyomata uteri. Fertil Steril. 1988;49:404–409.

13 Carr BR, Marshburn PB, Weatherall PT, et al. An evaluation of the effect of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs and medroxyprogesterone acetate on uterine leiomyomata volume by magnetic resonance imaging: a prospective, randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;76:1217–1223.

14 Hibbard LT. Adnexal torsion. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;152:456–461.

15 American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2009. Atlanta: American Cancer Society. 2009.

16 Wheeler JM. Epidemiology of endometriosis-associated infertility. J Reprod Med. 1989;34:41–46.

17 Rawson JM. Prevalence of endometriosis in asymptomatic women. J Reprod Med. 1991;36:513–515.

18 Chan JK, Teoh D, Hu JM, et al. Do clear cell ovarian carcinomas have poorer prognosis compared to other epithelial cell types? A study of 1411 clear cell ovarian cancers. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;109:370–376.

19 Oltmann SC, Fischer A, Barber R, et al. Cannot exclude torsion—a 15-year review. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44:1212–1216. discussion 1217

20 Houry D, Abbott JT. Ovarian torsion: a fifteen-year review. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;38:156–159.

21 Nizar K, Deutsch M, Filmer S, et al. Doppler studies of the ovarian venous blood flow in the diagnosis of adnexal torsion. J Clin Ultrasound. 2009;37:436–439.

22 Cohen SB, Wattiez A, Stockheim D, et al. The accuracy of serum interleukin-6 and tumour necrosis factor as markers for ovarian torsion. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:2195–2197.

23 Daponte A, Pournaras S, Hadjichristodoulou C, et al. Novel serum inflammatory markers in patients with adnexal mass who had surgery for ovarian torsion. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:1469–1472.

24 Carlson KJ, Skates SJ, Singer DE. Screening for ovarian cancer. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121:124–132.

25 Shah CA, Lowe KA, Paley P, et al. Influence of ovarian cancer risk status on the diagnostic performance of the serum biomarkers mesothelin, HE4, and CA125. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:1365–1372.

26 Bar-On S, Mashiach R, Stockheim D, et al. Emergency laparoscopy for suspected ovarian torsion: are we too hasty to operate? Fertil Steril. 2010;93:2012–2015.