Gynaecology and obstetrics

Gynaecological imaging

13.2 Vulval carcinoma

1. Occurs in elderly women, mainly sixth/seventh decade.

2. Diagnosed clinically and confirmed on biopsy.

3. Staging according to FIGO classification.

4. Assessment of nodal disease is important prognostic factor.

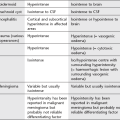

5. Tumour best seen on T2W scans and is of intermediate to high signal.

6. Early and en plaque disease may be difficult to recognize on MRI.

13.3 Uterine cervix

1. Not normally primarily imaged by US.

2. Best assessed clinically and staged by MRI.

3. FIGO staging used for clinical and surgical assessment.

4. Combined assessment with radiological findings influences prognosis and treatment decisions.

5. Specific MRI imaging – T2 scans axial to cervix, T2 sagittal to cervix and uterus.

6. MRI features – stage IA tumour may not be visible. Tumour normally hyperintense compared to myometrium and cervical stroma on T2 scans.

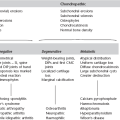

13.4 Uterine myometrium

Clinical and imaging features of benign disease

(a) Very common, usually benign, smooth-muscle tumour.

(b) > 20% of women over 35. More common in Afro-Caribbean women.

(c) Often asymptomatic and incidental finding on US.

(d) Present with menstrual disturbance, pelvic mass, pelvic heaviness, increased frequency, infertility, recurrent abortion.

(e) May be single or multiple, large or small.

(f) Defined by size and position – submucosal, myometrial or subserosal.

(g) May be extrauterine, e.g. broad ligament fibroid.

(h) Usually well-defined, heterogeneous but mainly hypoechoic pattern on US.

(i) Variable pattern seen in cystic degeneration.

(j) Check for involvement of adjacent structures, e.g. endometrium, ureters.

(k) MRI used for assessment pre-embolization and for follow-up.

(l) MRI also used for problem solving with indeterminate masses.

(m) Well-defined, isointense to myometrium on T1 scans.

(o) Become more heterogeneous on T2 as degeneration occurs.

(p) Haemorrhagic degeneration (red degeneration) shows high signal areas on T1 imaging.

(a) Defined as endometrial stroma and glands within myometrium.

(b) May be focal (adenomyoma) or diffuse.

(c) Presents later in menstrual life with pain, dyspareunia and dysfunctional bleeding.

(d) May be difficult to diagnose but can be effectively managed with a progesterone-impregnated intrauterine system.

(e) US shows increased focal reflectivity in the myometrium with asymmetric thickening of the myometrium. May show a focal adenomyoma.

(f) MRI is highly accurate, sensitive and specific.

(g) T2W scans show punctuate foci of high signal within the myometrium.

(h) Associated feature but less specific is thickening of the junctional zone > 12 mm.

Clinical and imaging features of malignant disease

(a) Thought to arise from pre-existing fibroid, usually but not exclusively postmenopausal.

(b) Lacks any specific features on US or MRI; impossible to accurately differentiate on imaging between benign fibroid and sarcoma.

(c) Large tumour size, ill-defined margins and rapid increase in size are all worrying features.

13.5 Uterine endometrium

Clinical and imaging features of benign disease

1. Normal endometrium varies across the menstrual cycle with most prominent thickening in the secretory phase.

2. Postmenopausal endometrium should be thin (< 4 mm) and homogeneous.

3. Endometrial hyperplasia can occur pre- and postmenopausally due to prolonged oestrogen exposure.

4. Endometrial polyps may be difficult to differentiate from endometrial thickening. Accuracy improved by performing sonohysterography. Power Doppler evaluation may demonstrate a stalk with a large entering vessel.

5. Endometrial thickening may be due to multiple processes:

6. Sometimes difficult to differentiate between an endometrial polyp and a submucosal fibroid. MRI useful as polyps show significant and persistent increased signal.

Clinical and imaging features of malignant disease

1. Commonest presentation is postmenopausal vaginal bleeding.

2. Endometrial carcinoma is the commonest gynaecological carcinoma.

(d) Family history of endometrial/colorectal carcinoma.

4. US useful for identifying endometrial thickening in symptomatic women but not good at staging.

5. MRI is the modality of choice to stage endometrial carcinoma diagnosed on sampling/hysteroscopy.

6. Combined staging performed according to the FIGO definition.

7. High-resolution scanning required using T2 sequences in the axial, sagittal and coronal planes, with a specific sequence axial to the plane of the uterus to assess the endometrium/myometrial junctional zone.

8. The depth of the myometrial invasion is critical to staging and subsequent surgical management.

9. Postgadolinium T1W sequences are sometimes useful to define the depth of myometrial invasion.

10. Staging more problematic in the presence of fibroids or adenomyosis.

11. Tumour appears slightly hypointense compared to endometrium but hyperintense compared to myometrium.

13.6 Ovary

Clinical and imaging features of benign ovarian disease

1. US is very sensitive at diagnosing ovarian lesions but is less specific at differentiating pathology.

2. Functional ovarian cysts are extremely common. Cysts < 3 cm are considered normal follicular cysts.

3. Most cysts are relatively asymptomatic until they become space occupying, although torsion, haemorrhage and rupture may be very painful.

4. Haemorrhage into a cyst alters the appearance and sometimes makes it difficult to exclude a more sinister lesion.

5. Simple cystic lesions in the pelvis:

(c) Theca lutein cyst (hydatidiform mole, etc.).

(e) Corpus luteal cyst (may be slightly echogenic due to blood).

(f) Dermoid cysts may rarely be purely cystic.

(g) Other cystic lesions, e.g. lymphocoele, bladder diverticulum, urinoma, loculated fluid.

6. Polycystic ovaries. Not necessarily related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Consensus is that the US diagnosis of a polycystic ovary depends on an overall increase in size of the ovary to 10 ml or greater and/or 12 or more subcapsular follicles measuring 2–9 mm in diameter.

7. Ovarian remnant syndrome. Post-bilateral oophorectomy a pelvic cyst may be due to a small amount of residual functioning ovarian tissue.

8. Endometriosis is not easily diagnosed in stage 1 or 2 disease but larger endometriomas are well recognized on US. They present as well-defined, diffusely hypoechoic cysts with ‘low-level’ echoes throughout. They may contain fluid–fluid levels owing to blood of different ages being present.

11. US is primary imaging tool with MRI reserved for differentiating the indeterminate mass lesion. Additional fat suppression sequences are useful for evaluating the size and extent of dermoid tumours.

Clinical and imaging features of malignant ovarian disease

1. Ovarian cancer is second most common gynaecological malignancy but with highest mortality rate owing to late presentation at an advanced stage.

2. Presents in middle and old age with a preclinical stage of 2 years on average.

4. No single screening programme has yet been defined, although postmenopausal serum testing with CA125 and annual US screening of ovarian size and morphology are being promoted.

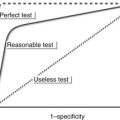

5. US is currently imaging modality of choice, although problems with indeterminate lesions (up to 20%) limit its effectiveness in early carcinoma.

6. Significant US features of malignancy are:

7. NICE guidance 2011 recommends using the above US features, menopausal status and CA125 reading to calculate a Risk of Malignancy Index (RMI) to determine management.

8. Tumours of borderline malignancy are diagnosed in up to 15% of oophorectomy cases as they lack any specific features to confirm benign or malignant disease.

9. Ovarian malignancies include:

(a) Serous cystadenocarcinoma.

(b) Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma.

(e) Dysgerminoma (lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) elevated in 90%).

(g) Ovarian metastases (Krukenberg tumours) usually of gastrointestinal tract origin (50%).

10. Yolk sac tumour is an aggressive tumour of adolescence with a good prognosis with modern treatment regimes. Associated with elevated α-fetoprotein and used to monitor treatment.

11. CT is currently the staging investigation of choice, principally to assess extent of intraperitoneal spread of disease.

13.7 Adnexa

Clinical and imaging features

Commonest adnexal problems relate principally to the fallopian tube and infection (see 13.16 for ectopic gestation). These are best imaged with US, although MRI is useful for problem solving in difficult cases.

1. US appearance may be completely normal in acute PID.

2. Vague adnexal mass and free fluid are consistent with acute PID but the clinical and biochemical features are important discriminators.

3. Doppler is useful in the acute phase to confirm increased vascularity.

4. In the acute phase of PID there may be additional features of endometritis with fluid and even air within the endometrial cavity.

5. Chronic changes of tubal dilatation are well seen on US. This can be confirmed by MRI, hysterosalpingography or laparoscopy.

6. MRI is useful to differentiate a dilated tube from a complex ovarian cyst.

Ascher, S. M., Horrow, M. M. Editor’s page: The 2012 RadioGraphics monograph issue: Gynecologic imaging across the life span. Radiographics. 2012; 32:1573–1574.

Bates, J. Practical gynaecological ultrasound. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2006.

Brown, M. A. MR imaging of the female pelvis. Magnetic resonance imaging clinics of North America. New York: Elsevier Saunders; 2006.

NICE Clinical Guideline 122. Ovarian cancer: the recognition and initial management of ovarian cancer; April 2011.

Sala, E., Wakely, S., Senior, E., et al. MRI of malignant neoplasms of the uterine corpus and cervix. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007; 188:1577–1587.

Sohaib, S. A., Mills, T. D., Webb, J. A. W., et al. The role of magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound in patients with adnexal masses. Clin Radiol. 2005; 60:340–348.

Sohaib, S. A., Reznek, R. H. MR imaging in ovarian cancer. Cancer Imaging. 2007; 7:S119–S129.

Spencer, J. A., Ghattamaneni, S. MR imaging of the sonographically indeterminate adnexal mass. Radiology. 2010; 256:677–694.

Obstetric imaging

13.8 Normal pregnancy

First trimester imaging

1. US assessment of gestational age is recommended as being more accurate than last menstrual period. This allows better management of post-term pregnancies, second trimester serum screening programmes and serial growth measurements where fetal growth restriction is present/suspected.

2. US should not be used to routinely diagnose pregnancy.

3. Where 1st trimester combined Down’s screening is offered, the scan should ideally be performed between 9 weeks 0 days and 13 weeks 6 days to facilitate the detection and measurement of nuchal translucency.

4. When scanning is performed between 11 and 14 weeks, there is an increased rate of detection of fetal abnormalities, e.g. neural tube defects, renal, cardiac and limb abnormalities. This, however, is not the current rationale for 1st trimester screening.

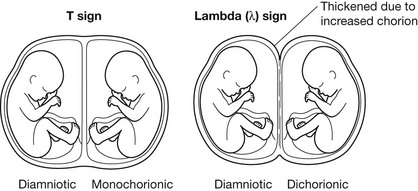

5. Where a multiple pregnancy is present, the chorionicity is best determined on this early scan by assessment of the intersac chorion. This assessment is less accurate in later gestation. See diagram.

Second trimester imaging

1. Fetal biometry assessed by measurement of head circumference (HC), biparietal diameter (BPD), abdominal circumference (AC) and femur length (FL). Other measurements can be made as required, e.g. cerebellar diameter, humeral length. The recommended principal measurements are the HC and FL (BMUS). Standardized national charts are also recommended (BMUS).

2. Fetal anatomical checklist recommended, along with exclusion of potential abnormalities (Fetal Anomaly Screening Programme).

3. Placental site assessed. Where the placenta crosses the internal os, a repeat scan is advised at 36 weeks, gestation to assess status prior to decision-making about mode of delivery (NICE).

13.10 Fetal growth restriction

13.12 Multiple pregnancy

1. Chorionicity best assessed on early pregnancy scan (see above).

2. Importance of careful assessment and management of twins is emphasized by the increased fetal loss of twins generally and monochorionic twins in particular. Intrauterine loss is seven times greater in twins than in singleton pregnancies and is highest in monochorionic, monoamniotic pregnancy.

3. Monochorionic twins have an increased rate of fetal anomalies, increased shared vascular connections leading to twin–twin transfusion and acardiac twinning, increased cord entanglement and increased complications in the event of the death of one of the twins.

4. Major issues with Down’s screening in multiple pregnancy as serum screening is not effective. Nuchal translucency assessment is likely to be the way forward, although multiple issues arise when interventional assessment is required for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes, e.g. amniocentesis and subsequent fetocide.

13.13 Abnormalities of the placenta

Other placental abnormalities

1. Placental abruption – premature separation of a normal sited placenta. Associated with maternal hypertension, vascular disease, smoking, drug abuse, trauma and presence of fibroids.

2. Placental lakes – normal variant.

3. Succenturiate lobe – accessory lobe attached to main placental vessels.

4. Placenta accreta/increta/percreta – varying degrees of direct placental invasion of the myometrium by chorionic villi. Frequency increased in placenta praevia and increases further in the presence of previous Caesarean section. Repeated Caesarean section significantly increases the risk further.

5. Chorioangioma of placenta – benign tumour of placenta. May be associated with pregnancy complications if > 5 cm or diffuse in nature. Vascular shunting in large tumours may cause hydrops, restricted fetal growth, etc.

13.14 Gestational trophoblastic disease

Hydatidiform mole (classic mole/molar pregnancy)

1. Diagnosed during early pregnancy with US features of a large echogenic vesicular mass filling the uterus.

2. Associated with hyperemesis, early pre-eclampsia and vaginal loss of cystic material.

3. In early pregnancy, appearance may be confused with hydropic degeneration of the placenta in a failed pregnancy for other reasons. Differential diagnosis also includes retained products.

4. Mole usually associated with abnormally raised hCG levels and may have abnormal ovarian stimulation with large theca lutein ovarian cysts (30–50%).

5. May rarely have a normal fetus with a coexistent molar pregnancy. This is due to molar degeneration of a dizygotic twin.

Choriocarcinoma

2. Half are associated with previous molar pregnancy.

3. Also associated with spontaneous abortion (25%), normal pregnancy (22%) and ectopic pregnancy (3%).

4. Present with persistently elevated hCG after successful or failed pregnancy.

5. Uterine mass as with molar pregnancy but likelihood of myometrial invasion and distant metastases to liver, lung, brain, bone and gastrointestinal tract.

13.15 Early pregnancy bleeding

Causes and features

2. Pregnancy failure – threatened/missed/incomplete miscarriage.

(a) Viable fetus identified in up to 50%. Remainder have a variable-size fetal pole but with no fetal heart activity or movement. An irregular sac is often present.

(b) Fetal pole > 7 mm in length with no fetal heart pulsation.

3. Pregnancy failure – anembryonic gestation (early fetal demise).

13.16 Ectopic gestation

US findings

1. No evidence of an intrauterine pregnancy (but beware early gestation), now known as ‘pregnancy of unknown location’.

2. Endometrial thickening – pseudogestational sac.

3. Fluid in pelvis (often slightly echogenic as usually blood).

4. Adnexal mass – often complex.

5. Live fetus/fetal cardiac activity outside uterus occurs in about 10%.

6. Absence of US abnormality does not exclude ectopic gestation.

7. Live intrauterine gestation normally excludes the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy but beware the coincidental ectopic twin gestation (approx. 1:30,000 in unstimulated population).

8. Empty uterus with hCG > 1800 IU/L is highly suggestive of ectopic.

Bisset, R. A. L., Khan, A. N., Thomas, N. B. Differential diagnosis in obstetric & gynaecological ultrasound. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2002.

Callen, P. W. Ultrasonography in obstetrics and gynaecology. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2000.

National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children Health. Antenatal care: routine care for the healthy pregnant woman. Commissioned by the National Institute for Clinical Excellence. London: NCCWCH; 2003.

NICE Clinical Guideline 154. Ectopic pregnancy and miscarriage; December 2012.

Twining, P., McHugo, J., Pilling, D. Textbook of fetal abnormality. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2006.