30. Grief and Perinatal Loss *

Sandra L. Gardner and Lorraine A. Dickey

As a life passage, pregnancy and birth are associated with hopes and expectations and joy and happiness for the future. Even though pregnancy and birth constitute a developmental crisis and major life change, expectant parents believe the gains of a healthy, happy child and family life offset any losses. Unfortunately, not all perinatal events have a happy ending. When pregnancy fails to produce a normal, healthy infant, it is a tragedy for the parents whose expectations of childbearing have not been fulfilled. Perinatal loss also affects their friends, family, and professional care providers.

Perinatal loss may be the first time a young adult has had the experience of coping with the illness or death of a loved one. Perinatal loss is especially significant because it (1) is sudden and unexpected, (2) is the most difficult loss to resolve18; (3) interrupts the significant developmental stage of pregnancy and the situational crisis of pregnancy18; (4) is the loss of a child who did not have the opportunity to live a full life36,101; (5) prevents progression into the next developmental stage of parenting that has been anticipated and rehearsed (at least in fantasy) during the pregnancy64; and (6) represents a narcissistic loss, a loss of self, for the parents. 96,119,120 Perinatal loss also often means interpersonal exclusion from the activities of childbearing friends and siblings.

Unfortunately, loss and grief often are thought of only in relation to death. However, as final and irreversible as death is, it is just one form of separation and loss. Although less obvious, other loss situations may have an equally crucial effect. Loss comes in many forms, and during the perinatal period, may occur without necessarily resulting in death. Circumstances of perinatal loss are parallel and, at the same time, different, because they all entail grief and mourning and yet each has unique dimensions and characteristics. The process of grief, its stages, and its symptoms are reviewed as a framework for understanding one’s own feelings and those of others experiencing a loss. A desire to help and an idea of what is helpful and what is not helpful are essential for effective intervention by professionals.

THE GRIEF PROCESS

Grief, the characteristic response to the loss of a valued object, is not an intellectual and rational response. 38 Rather, it is personally experienced as the deep emotion of sadness and sorrow. To the individual, grief feels overwhelming, irrational, out of control, “crazy,” and all-consuming. Mourning occurs in phases over time. After acknowledgment that the loved object no longer exists, gradual withdrawal of emotion and feeling occurs, so that eventual psychologic investment in a new relationship is possible.

A recent literature review of the theoretical perspectives of parental grief from the United States and United Kingdom reveals a change from a traditional to a “newer” model of grief in the Anglo-American culture. 29 Traditional models of grief emphasize the severing of bonds with the deceased, whereas “newer” understandings of parental grief emphasize parents retaining a relationship with their dead child. After reviewing nursing, medical, and social science publications and choosing relevant ones, Davies states: “…the concept of continuous bonds challenges the dominant assumption that resolution of grief is achieved through severing bonds with the deceased.”29 Parents wish to know that their child’s birth and death have meaning and purpose and that their child “mattered” and will be remembered by them and by others who have been “touched” and “changed” by him or her. 19

For grief to occur, the object must have been valued by the individual so that its loss is perceived as significant and meaningful. Because, prenatally, there is an investment of love in the fetus or newborn, the neonate is a valued object. To the extent that prenatal attachment has occurred, grief should be expected and felt at the loss of the fetus or newborn. Therefore loss at birth is a significant loss of a valued (although as yet only fantasized) person.

Loss, whether real or imagined, actual or possible, is traumatic. The individual is no longer self-confident or confident about the surroundings, because both have been altered. Mourning and grief are forms of separation reactions. Fears of separation and abandonment are the universal fears of childhood regardless of age or developmental stage. Perhaps loss of a significant other awakens these childhood fears and reminds us of the basic “insecurity of all our attachments.”68

Life changes are stressful to the individual because they threaten to disrupt continuity and a state of equilibrium. 88 Significant changes in the family configuration, such as accession of a new member, are normally a stressful occasion for family members. Perinatal complication or loss is even more of a stressful event for which the family has little or no preparation. The result of a crisis may be personal growth, maintaining the status quo, regression, or mental illness. 18,89 Often outcome depends on the type of help received during the crisis.

Decreasing the element of surprise through preparation for the situation to be encountered may modulate the effect of the event. Anticipatory grief 61,79,100 functions both to prepare and to protect the individual from the pain of impending loss. Prenatal diagnostic procedures, such as ultrasonography, 75 amniocentesis, and fetoscopy, can now detect a variety of severe or lethal birth defects. When there is forewarning that the pregnancy or newborn is not healthy, the parents may begin a process of anticipatory grief and psychologically prepare for the loss of their baby while hoping for his or her survival. 7

Parental withdrawal from the relationship established during pregnancy accompanies the intense emotions of anticipatory grief. Detachment protects and defends the parent from further painful feelings associated with the investment of self in a doomed relationship. If anticipatory grief proceeds, the parent may detach to the point of being unable to reattach to the infant if he or she survives. In this situation, the infant survives but the relationship with the parents may be significantly impaired. Maintaining even a remote hope that the fetus or newborn will survive protects the parents from the full experience of grief and total detachment from the baby.

The degree of parental anticipatory grief is correlated with positive feelings about the pregnancy and the mode of delivery but not with the severity of the infant’s illness. The greater the parental investment and the higher the expectations for the pregnancy, the more anticipatory grief is associated with the development of a perinatal complication. The relative severity of the medical problem is not associated with the degree of anticipatory grief.

PERINATAL SITUATIONS IN WHICH GRIEF IS EXPECTED

Loss is a fact of life, not just of death. Every stage of development requires a loss of the privileges of the preceding stage and movement into the unknown of the next stage. Any life event involving change or loss is accompanied by grief work, including moving, divorce, separation, death of a spouse or family member, injury or illness, retirement, job change, menopause, and even success. 88 The concept of loss is even applicable to the physiologic and psychologic events of normal pregnancy and birth. Certainly, when pregnancy fails to produce a live, healthy infant, a perinatal loss situation exists (Box 30-1). These perinatal losses, including stillbirth, loss of the perfect child, and neonatal death, are discussed in detail in this chapter.

BOX 30-1

1. Pregnancy

2. Birth

A. Normal

B. Cesarean section

C. Forceps

D. Episiotomy

E. Medicated

F. Prolonged or short labor

G. Place of birth

3. Postpartum (see Chapter 29)

A. “Postpartum blues”

B. Depression

C. Psychosis

4. Abortion

5. Stillbirth

6. Loss of the perfect child

7. Neonatal death

8. Relinquishment

Stillbirth

Stillbirth is the demise of a viable fetus that occurs after fetal movement when the fetus is invested by the parents with a personality and individuality. Because stillbirth occurs later in pregnancy than most abortions, there are increased parental expectations about the baby and the birth process. Selective abortions for genetic indications often are performed in the second trimester of pregnancy and involve the death of a wanted child. Even though parents understand the validity of the reason for terminating the pregnancy, sadness, guilt, and self-doubt often accompany the decision to abort. The anxieties related to termination procedures, which may include labor and birth, and the feelings of helplessness, isolation, and depression should be acknowledged and handled as in a stillbirth.

Fetal demise in utero happens either prenatally or in the intrapartum period. For 50% of stillbirths, death was sudden, without warning, and occurred from unexplainable causes. The majority of women whose fetus has died in utero spontaneously begin labor within 2 weeks of fetal demise. Carrying the dead fetus while waiting for spontaneous labor or induction is sad and difficult for the woman and her entire family. Feelings such as helplessness, disbelief, and powerlessness characterize this period. There is often an almost uncontrollable urge to flee and escape the unpleasant situation.

For the family who experiences an intrapartum demise, the joyous expectations of labor and birth suddenly change to fear, anxiety, and dread that the “worst” could have possibly happened to them. The suddenness of fetal demise in labor and birth affects both parents and professionals with feelings of shock, denial, and anxiety. Whether the loss is an early or late fetal loss, the woman and her family maintain hope by believing that the professional has made a mistake and that the fetus is still alive. 99 The onset (or continuation) of labor is approached with both hope and dread: hope that the infant may be born alive and dread that the infant’s death will soon be a stark reality.

The discomfort of labor and birth is particularly difficult for the woman whose fetus has died, because her work will not be rewarded with a healthy infant. However, oversolicitous use of drugs at birth is not recommended, because they relegate the experience to unreality and give it a dreamlike quality. 128 Keeping parents together through this crisis is important for mutual support and sharing of the birth. 97 The deadening (and deafening) silence of a stillbirth forces the reality of the infant’s death on both the parents and the professionals present at birth. 97

In the past, at the birth of a stillborn, the mother was heavily sedated or anesthetized and the neonate was hidden and whisked away immediately. These women were often left with fears and fantasies: “Was the baby normal?” “What was the sex?” “What did the baby look like?” Seeing, touching, and holding the infant promote completion of the attachment cycle, confirm the reality of the stillbirth for both parents, and enable grief to begin. 10,99,128

Because it is easier to grieve the reality of a situation than a mystical and dreamlike fantasy, contact with the stillborn enables parents to grieve the infant’s reality rather than endure their most frightening fantasies about him or her.

After confirming the reality of the infant’s death, a search for the cause, characterized by the universal question “Why did the baby die?” begins. Either or both parents may blame themselves or feel guilty about real or imagined acts of omission or commission. An autopsy may determine the cause of death, but most often the cause is unknown, even after an autopsy. However, an autopsy may be useful in reducing parental guilt and uncertainty about future pregnancies, as well as in aiding the recovery from the loss. 72,128 The “empty tragedy” of stillbirth forces the mother to deal with both the inner loss of the fetus and the outer loss of the expected newborn. Fathers experience stillbirth as a “waste of life,” are especially appreciative of the tokens of remembrance from the baby, and need help in expressing their grief. 97

Loss of the Perfect Child

Even though pregnancy ends in the birth of a live newborn, the pregnancy outcome may not be what the parents had anticipated. Birth of an infant who does not meet parental expectations represents the realization of the parents’ worst fears: a damaged child. Newborns who are preterm, have an anomaly, are sick, or are the “wrong” gender or who ultimately die represent the loss of the fantasized perfect child.

After the birth of such a infant, parental reactions include grief and mourning for the loss of the loved object (the perfect child) while adapting to the reality and investing love in the defective baby. 42,106 This reaction is analogous to parental mourning at the death of a child. 106 However, unlike the finality of death, birth of a living, defective baby entails a persistent, constant reminder of the feelings of loss and grief because of parental investment of time, attention, and care for either a short time (preterm or sick newborn) or a lifetime (physically or mentally afflicted child). 91,106

The psychic work involved in coping with the reality of the imperfect child and the inner feelings of loss is slow and emotionally painful. 40,91 The process is gradual and proceeds at an individual pace that cannot be hurried but can be facilitated and supported. Detachment from and mourning the loss of their fantasized child is necessary before parents are able to attach to the actual child.

Birth of an imperfect infant represents multiple losses for parents. A primary narcissistic injury, a threat to the female’s self-concept as a woman and mother and the male’s self-concept as a man and a father, occurs when a less-than-perfect infant is born. 27,28,40,58 Because the child is an extension of both parents, a less-than-perfect (i.e., deformed) child is equated with the perceived less-than-perfect part of the parental self. In the mind of the parent, the imagined inadequate self has failed and caused the birth of the damaged baby. 58

Prematurity

Every woman expects to deliver a normal, healthy infant at term. Therefore the onset of premature labor is both physiologically and psychologically unexpected. Premature birth is a crisis and an emergency situation characterized by an increased concern for the survival of the newborn and often the mother. Premature labor and birth are accompanied by feelings of helplessness, isolation, failure, emptiness, and no control. 58,106 The negative and dangerous atmosphere surrounding the premature birth experience may influence the relationship with the premature infant, who also may be perceived as dangerous and negative.

Normal adaptations to pregnancy are abruptly terminated by the birth of a premature infant. 58 Prenatal fantasies about the infant and the new roles of mother and father are interrupted by a premature birth. This forces parents who are “not ready to not be pregnant” to grieve the loss of a term infant and imposes premature parenting on individuals not yet ready for the experience.

As discussed in Chapter 29, anticipatory grief is one of the normal psychologic tasks accompanying premature birth. Anticipatory grief may be decreased by early contact between parents and neonate and, conversely, increased by separation of parents from preterm newborn. 58 Prolonging anticipatory grief with failure to progress through the other tasks results in altered relationships with the parents if the preterm infant survives.

Deformed Infants or Infants with an Anomaly

In approximately 2 of every 100 births, 58 an infant is born with a birth defect. Because society values physical beauty, intelligence, and success, the birth of a physically or mentally defective baby is seen as a catastrophe in our culture. 127

Recent medical advances now make it possible to identify potential fetal problems in utero. As parents receive the information antenatally, they begin the process of anticipatory grief. They experience feelings of shock, anger, guilt, and hope. At the birth of their baby, there usually is the confirmation of the anomaly, and parents must deal with the reality of the situation. Whether anticipated or not, however, the birth of a baby with a congenital defect is accompanied by ambivalent feelings for all concerned (parents, relatives, friends, and professionals). The first reactions to the reality of the situation are feelings of disbelief and shock. Feelings of shame, revulsion, and embarrassment at creating a damaged and devalued child are common. 104 Guilt, self-blame, and a search for a cause or reason for the tragedy are intermixed with feelings of anger.

The severity of loss and feelings of disappointment heavily burden the parents, a burden they may believe that no one else has experienced. 58 Their loneliness and isolation may be intensified by their self-imposed withdrawal from others. Unlike the birth of a healthy infant, the birth of a sick baby or one with an anomaly is not celebrated by society with announcements, visits, and gifts from friends and family. The negative responses of society’s representatives (family, friends, acquaintances, and professionals) may increase the parents’ negative feelings for a defective child. 127

The extent of the infant’s anomaly cannot be used as a criterion for the degree of parental grief reaction, although a gross, visible anomaly may elicit more emotional reaction than a hidden or minor one. 58 A seemingly “minor” anomaly as defined by the professional may represent a severe impairment to individual parents. The professional, who has had more contact with infants with a wide range of anomalies, views the individual infant’s anomaly in a different context than that typical for the parents, who may have limited or no experience with a deformed child or adult. The professional also views the infant’s defect from a less personal, more objective, and less narcissistic position than the new parents.

When the newborn is sick, the degree of mourning and parental feelings of grief and loss are not equated with the severity of the neonate’s illness. 7,105 Even seemingly minor illnesses such as jaundice or respiratory difficulty requiring phototherapy or minimal oxygen supplementation are associated with parental concern for survival and feelings of grief and loss. 78 These feelings are often not acknowledged by the parents or professional care providers because of the non-serious medical nature of the condition. In the mind of the care provider, self-limiting and treatable conditions are compared with more serious and often fatal neonatal illnesses. The care provider feels relieved about the “minor” nature of the neonate’s condition and conveys this to the parents—“This is an easy condition to remedy. You don’t have anything to worry about. The baby will go home in a few days.”

Thus only the medical aspects of the newborn’s illness are dealt with, whereas parental feelings remain unspoken and unresolved. 16 In an altruistic attempt to reassure and comfort the family about the newborn’s complete recovery, the professional unwittingly may discount the parents’ real feelings. If the care provider is not concerned, parents may feel that they, too, should not be concerned and thus distrust and discount their own feelings.

Neonatal Deaths

The reactions accompanying neonatal illnesses are similar to the grief reactions experienced by parents whose infant dies. 7,123 Failure to acknowledge (even minor) neonatal illness as a loss situation and to work through the associated grief prevents parents from detaching from the image of the perfect child and taking on the sick newborn as a person to love. This may result in an aberrant parent-infant attachment. The liveborn infant who is critically ill or has a severe anomaly will be the focus of a “painful time of waiting”10 for the family. They must deal with the uncertainty of whether their child will live and be healthy, live and continue to need extensive medical or special care, or die.

More deaths occur in the first 24 hours of life than in any other period of life. Yet death of a newborn is not the expected outcome of pregnancy. The majority of neonatal losses are caused by prematurity (80% to 90%) and congenital anomalies that are incompatible with life (15% to 20%). Regardless of the cause of death, even infants who live only a short time are mourned by their parents. 56 Prenatal attachment and investment of love in the newborn result in a classic grief reaction at the newborn’s death.

Even a short period of life between birth and death gives parents an opportunity to know and take care of their infant. 108 Completion of the attachment process enables parents to psychically begin the next process of detachment. Attachment to the baby’s reality encourages detachment from that reality rather than from the parents’ most dreaded fears and fantasies about their infant. Parental contact with the child before death enables them to share life for a brief time.

In the case of multiple births, when one infant or more dies and the others live, parents simultaneously grieve the loss of the dead infant while attaching to the survivor. 60,82,83,110 In many situations of multiple birth, the surviving infant or infants are in an intensive care nursery. The diametrically opposite feelings of love and attachment and grief and detachment, as well as the anxiety associated with the care and well-being of the surviving infant, are emotionally draining for new parents. The process of grief may slow the parents’ ability to become intimately involved with their surviving infant(s). 83,84,124 They may have ambivalent feelings toward the infant(s) who survives or toward the infant(s) who dies. With the loss of one infant of a multiple birth, there is less support for the grieving parents because the frequent response is that they should be thankful for the survival of one (or more) of their infants. Research shows that the death of a twin (or higher-order multiple) is as great a loss for a mother as the death of a singleton. 82,83,110 Helpful interventions include (1) acknowledging the uniqueness of every baby; (2) viewing, holding, and photographing the babies together—living and dead; (3) private time with each deceased infant; and (4) similar mementos and keepsakes from each infant, deceased and living, given to the parents. 82.83. and 84.

Generally, death of a newborn occurs despite everything done to prevent it. This provides parents with some measure of comfort in knowing that they did everything possible. Yet when the neonate is so severely ill or deformed that a decision about initiating or continuing life support is necessary, the parents have an extra burden. The situation may involve conflicts between physicians, nurses, and family wishes, causing significant personal anguish. As part of the federal Baby Doe regulations, most hospitals now have ethics committees that address the medical, legal, and ethical controversies (see Chapter 32). The decision-making process may be collaborative, parent initiated, directive, or nondirective. 82 Regardless of who makes this decision, it is primarily the parents who will live with the ramifications of that decision. When parents are involved in the decision-making process, they wonder if theirs was the right decision regardless of the decision. Whether the baby lives or dies, they wonder how a different decision would have changed their lives.

STAGES OF GRIEF

The experience of grief is a staged process that occurs over time. To detach both externally and internally from the lost loved object, emotional investment is withdrawn so that it may be invested in new love relationships. 61 Each stage of grief represents a psychologic defense mechanism used to help the individual adapt slowly to the crisis. This slow adaptation is purposeful, because it prevents the individual psyche from being overwhelmed by the pain and anguish of loss. 81

Although the stage of grief is recognizable, the process of grief is dynamic and fluid rather than static and rigid. Parents, families, and professionals progress cyclically through the stages of grief rather than in an orderly progression from beginning to end. However, each person experiences the process of grief uniquely and at an individual rate. Knowledge of each stage is necessary to assess where an individual family member, the family as a unit, and the staff are in their grief process. This information is then used to support individuals when they are in their particular stage of grief. Rather than attempting to maneuver grieving individuals from stage to stage, contributing to their defense, or stripping individuals of their defenses, knowledgeable professionals are prepared to understand and honor the individual’s grieving process. Regardless of the type of perinatal loss, the experience of that loss through staged grief work closely parallels the grief stages described by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross. 59

The feelings of disbelief and rejection of the news are reflected in the responses “No! This couldn’t happen to me!” “It isn’t true! They’ve made a mistake!” This immediate response protects the individual from the shocking reality of loss by postponing the full effect of reality until the psyche can handle it. 99 By holding on to the fantasy of a positive outcome (e.g., the loss of the heartbeat is only temporary or the dead infant belongs to someone else), facing the awful truth and the grief associated with it is delayed at least temporarily. 99

The initial stage of grief is characterized by overwhelming feelings of being stunned and surprised. This is often seen as emotional numbness, flat affect, or immobility. 128 Emotional detachment is often expressed as an inability to cope or respond with activities of daily living, an inability to remember what others have said, and a tendency to repeat the same question. 31,36 For the tragedy to be handled in manageable pieces without overwhelming the individual, the mind may acknowledge the event only intellectually and there is a corresponding lack of emotional reaction, 128 or the event may be compartmentalized so that only a part of the situation rather than the whole becomes the focal point of attention.

Anger is the result of a gradually developing awareness of the situation’s reality. As the significance of their perinatal loss begins to dawn on them, parents (and significant others) experience the diffuse emotions of anxiety and anger. 58 With the full effect of their loss comes more focused feelings of bitterness, resentment, blame, rage, and envy of those with normal pregnancy outcomes. 59

Social prohibitions against the expression of anger, especially for women, encourage this powerful emotion to be turned inward toward the self. Anger directed inward results in depression and a deepening sense of guilt. “Why?” and “What did I do wrong or not do right to have caused this to happen?” are the hallmarks of the self-examination and self-blame that accompany perinatal loss. 58,128 Answers are often irrational and have no cause-and-effect relationship with the reality of the circumstances. Irrational, feared causes include sexual intercourse (common worry of both men and women), career (of the mother) outside the home, superstitions, dietary habits, or lifting heavy objects. 128 Ideas of punishment (for past wrongs, for negative or ambivalent feelings, or for an unwanted pregnancy) 8 are often thought to be the reason for the failed outcome. The search for a reason to answer the question “Why me?” requires correct information to dispel unrealistic fantasies of causation. However, the question does not require a literal answer (often no concrete answer exists) but is merely a wish for a change in the situation. 8

Anger directed outward is usually expressed as overt hostility to those in the immediate environment (family, children, care providers, and infant) 128 or toward God. 81 Fathers exhibit more anger than mothers do. 44 Blame and anger may be destructive forces in the relationships among family members and prevent these relationships from being a source of comfort and support. Venting of angry feelings toward professional care providers protects these family relationships for more positive interactions. Anger moves the grieving process along, but persistence of anger may prevent grief work from progressing to subsequent stages.

Bargaining may occur concomitantly with denial and shock as an attempt to prevent or at least delay the loss. Bargaining usually occurs with whoever the parents (family or staff) believe the Supreme Being is. The “Yes, but” of this stage is a form of “conditional acceptance” while still attempting to make the reality other than what it is. 8,59 With the defective infant, bargaining may take the form of shopping for a physician or searching for the magic cure. 127

The onset of depression and withdrawal marks the stage of a greater level of acceptance of the tragedy. With the true realization of the effect of the loss, the individual acknowledges that indeed there is a reason to be sad. The predominant feelings of this stage are overwhelming sorrow and sadness72 evidenced by tearfulness, crying, and weeping. 99 Feelings of helplessness, worthlessness, and powerlessness contribute to the sense that life is empty and futile. Withdrawal may be evidenced by requests to be left alone, by decreased or complete cessation of visits to the infant, and by silence. 59 The degree of withdrawal may be indicative of the depth of depression and the extent to which there is guilt and self-blame. 99

Acceptance is the resolution stage of the grief process that is heralded by resumption of usual daily activities and a noticeable decrease in preoccupation with the image of the lost infant. 61 This stage usually is not witnessed by the perinatal professionals. The acceptance stage is characterized by emotional detachment of life’s meaning from the lost relationship and reestablishing it independent of the lost object. 59,68 The lost relationship is seen in a new light—as giving meaning to the present. 68 The aggrieved person relinquishes that part of himself or herself that was defined in the lost relationship and establishes a new identity that is emotionally free to attach in another relationship.

For the family of a deformed child, acceptance is not an all-or-nothing proposition but, rather, a daily adaptation and coping with the child and the defect. 103 For the family, periods of frustration and sorrow alternate with periods of delight and enjoyment of the child. Because of the chronic sorrow experienced throughout the life of a defective child, the final stage of resolution of the family’s grief is possible only after the child’s death. 79,127

The acceptance stage represents the ability to remember both the joys and sorrows of the lost relationship without undue discomfort. 38 With gradual integration of the loss, there are progressively fewer attacks of acute, all-consuming pain. 68 When recalling the lost infant, there are fewer feelings of devastation and more a feeling of sadness. The ability to “celebrate the loss” also identifies grief resolution. Celebration of the loss does not mean recall without sadness and sorrow but with an ability to find some meaning, some good, and some positive aspects in the situation (e.g., “At least we had our child for a time, even though it was a short time”).

SYMPTOMS OF GRIEF

Although each person copes with grief in individual ways, there are expected reactions to loss situations. Knowledge of the differences and commonalities of the grief experience enables care providers to understand their own reactions, as well as to share their thoughts and feelings with the grieving family. The professional care provider must learn to “hear” what the family says about how and where each member is in the process of grief resolution. Often the “message” is not a direct reference to the loss or one’s feelings but, rather, nonverbal communication. The professional must learn to recognize that individuals often communicate more by what they do and what they omit than by what they say.

The signs and symptoms of acute grief have been well described and include both somatic and behavioral manifestations of the emotional experience of the loss (see the Critical Findings box below). The behavior of the bereaved is characterized as ambivalent. 68 In certain perinatal situations, parents simultaneously hope that the infant will live and wish for the infant to die; they want to love and care for the infant and at the same time wish to reject him or her. 58 These feelings are frightening and socially unacceptable and therefore often remain unspoken.

Signs and Symptoms of Grief

1. Somatic (physiologic)

a. Gastrointestinal system

Anorexia and weight loss

Overeating

Nausea or vomiting

Abdominal pains or feelings of emptiness

Diarrhea or constipation

b. Respiratory system

Sighing respirations

Choking or coughing

Shortness of breath

Hyperventilation

c. Cardiovascular system

Cardiac palpitations or “fluttering” in chest

“Heavy” feeling in chest

d. Neuromuscular system

Headaches

Vertigo

Syncope

Brissaud’s disease (tics)

Muscular weakness or loss of strength

2. Behavioral (psychologic)

a. Feelings of:

Guilt

Sadness

Anger and hostility

Emptiness and apathy

Helplessness

Pain, desperation, and pessimism

Shame

Loneliness

b. Preoccupation with image of the lost infant

Daydreams and fantasies

Nightmares

Longing

c. Disturbed interpersonal relationships

Increased irritability and restlessness

Decreased sexual interest and drive

Withdrawal

d. Crying

e. Inability to return to normal activities

Fatigue and exhaustion or aimless overactivity

Insomnia or oversleeping

Short attention span

Slow speech, movement, and thought process

Loss of concentration and motivation

Often the intensity of grief is greater when the relationship with and feelings about the lost person are ambivalent. 68 Even with the most positive of pregnancy outcomes, taking a newborn into the family results in ambivalent feelings for all family members. The degree of disruption that a perinatal loss brings to the family is equated with the severity of grief, especially because reproduction and a healthy perinatal outcome are highly valued in our society. 68

MALE-FEMALE DIFFERENCES

Although members of both genders have the same grief reactions, women express more symptoms (crying, sadness, anger, guilt, and use of medications) 34,50,51,70,93 than men. This difference in symptomatology does not represent a different experience of grief but merely a different expression of it. Understanding these differences and the reasons for them is crucial for care providers working with parents at the time of perinatal loss. Explaining these differences to parents is also crucial so that diverse grief responses do not become divisive in the relationship. 34,93

The father’s degree of investment in the pregnancy, impending parenthood, and the circumstances of birth all affect his feelings of loss. Because the father’s body does not directly experience the changes of pregnancy, the pregnancy initially may be less of a reality to him than to the pregnant woman. This lag in the physiologic reality contributes to a lag in the psychologic investment of the father in the baby. The father’s lag in psychologic investment often contributes to incongruent grieving, a difference in mother’s and father’s grief reactions. Fathers often comment that the infant became real when he felt the fetus move in the mother or at first sight of the new infant. Fathers who form an early attachment to the child feel sadness, disappointment, and often anger at being denied the expected son or daughter. 44,55,70,71,97 Conversely, fathers who have been normally ambivalent or overtly negative about the pregnancy may feel guilt and responsibility for the failed outcome.

Participation of the father in the events of labor and birth also influences his attachment and ultimately his feelings of loss. Exclusion decreases his involvement in these life-crisis events, whereas inclusion has many advantages for the mother, infant, and self (see Chapter 29). If the infant is ill, the father may initially have more and closer contact than the mother. 7 In the birth place, the father may see, touch, or hold the infant before the mother does. The father observes the initial resuscitation and stabilization and may accompany the infant to the nursery and on transport to a regional center. Often the father receives the first information and support about the infant’s condition and returns to the hospitalized mother with the news. This early, prolonged contact coupled with the father’s increased responsibility often contributes to the development of a closer and earlier bond between father and infant than between mother and infant. The initial lag in prenatal investment may be offset after birth by concentrated contact between the father and the baby, so that a loss is highly significant to the father.

Societal expectations about masculinity and femininity markedly influence the expression of grief. Society’s message to men starts early in life: “Big boys don’t cry” and “Don’t cry, you’ll be a sissy” (i.e., girl). The preferred male image in our society is the autonomous, independent achiever who is always strong and in control, even in the face of disaster. 44,45 In keeping with this image, the father may feel that he must make all the decisions and have all information filtered through him to protect the mother. However, this altruistic gesture prevents full disclosure to and involvement of the mother. Assuming the role of strong protector also involves a heavy price for the father in suppression of his own feelings and delay of his own grief work. 34,71,93 The role of “tower of strength” often engenders feelings of resentment from the mother. Although he attempts to live up to his (and society’s) expectations of himself, the woman views his apparent lack of feelings and emotions, especially crying, as “He doesn’t care.” A recent study showed that distress experienced by the mother but not by her partner resulted in longer-term marital dissatisfaction for the mother.

Many men have difficulty dealing with irrational behaviors, as well as with the normal ambiguity and conflict of life. This difficulty makes the emotional response of grief and its accompanying ambivalent feelings and conflicts produce discomfort and anxiety in many men. The expression of appropriate human emotions becomes threatening and makes them feel vulnerable. To decrease the anxiety associated with grief and its expression, men often deal with feelings by denying them, increasing their workload, grieving internally, or withdrawing from the situation and refusing to discuss it. 70,93

The father’s attitude and ability to communicate about the loss may help or impede the mother’s grief work. 100 Lack of communication between a couple may contribute to intense mourning, psychiatric disturbances, and severe family disruption. 56,93,118 Synchrony of grieving between the mother and the father is important in an ultimate healthy resolution for the family. 22,93 If the father denies and suppresses his own feelings of loss and grief, he may react to the normal signs and symptoms of grief in his partner as if they were abnormal. Often the father can resolve his grief faster than the mother, and he may become impatient with her continual “dwelling” on the loss. Sometimes fearing the woman’s prolonged grief, the man decides to “spare her” from his feelings and does not discuss them with her. Instead of being comforting as intended, failure to share grief leads to isolation and alienation within the relationship. 58,93

In some situations, the man may experience intense emotions several months after the death, not unlike those his partner experienced at the time of the crisis. Because these intense emotions occur so long after the crisis, he may not even associate them with the death. 31,58 A recent study found that at 30 months after the death of a baby, fathers were more distressed than the mothers, who were the more distressed initially after the death. 118

TIMING OF GRIEF RESOLUTION

Parents

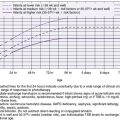

Emotional recovery from the pain of perinatal loss occurs with time. There is no complete agreement on the length of time necessary for the individual to resolve grief. Indeed, a specific timetable for mourning may be impossible to establish. 8 However, some general time frames are available for the duration of a normal grief reaction.

Acute grief reactions are the most intense during the first 4 to 6 weeks after the loss, 61,68,81 with some improvement noted 6 to 10 weeks later. Normal grief reactions may be expected to last from 6 months to 1 year 6,38,58,81 or 2 years. 68 Indeed, significant losses of a spouse or child may never be completely resolved29,96,119: “I’ll never get over it.”

One parameter for differentiating normal from pathologic grief has been the length of time for grief to be resolved. Grief work may still be categorized as normal even if it lasts longer than 1 year, especially if the person is working through unresolved grief from the past. Grief work is normally energy draining. Dealing with more than one grief or loss situation compounds the intensity of mourning and may prolong the grief reaction. Because perinatal loss represents more than the loss of the newborn (loss of the perfect child, loss of plans for the future, and loss of self-esteem), feelings of sadness and depression may still be evident for a year or longer. 58,70,118,128

Sorrow and grief may even last a lifetime. For families of defective children, “chronic sorrow”31,49,79,91,106 is experienced as long as the child lives. These parents live with the constant reminder of what is not and what the child will never be and can never do. The grief of death is final—parents do the work and go on; chronic sorrow is grieving on a daily basis. Expecting the parents to adjust to or accept their child’s defect without any elements of lingering sadness is unrealistic. Although hampered by small sample sizes, research on the gender differences in chronic sorrow show more chronic sorrow in mothers than in fathers. 49,67 Chronic sorrow is a justifiable reaction to the daily stresses and coping necessary when a child is defective. The final stage of grief resolution is possible only with the finality of the death of the child.

Even when grief has been resolved, anniversary grief reactions are normal. Feelings of sadness, crying, and normal grieving behaviors may be reactivated at certain times. These anniversary reactions may not be limited to the infant’s date of death but also may be felt on the expected date of delivery, on the actual birthday, or on seeing an infant of the same age and gender as the lost infant. Holidays may also reactivate grieving behaviors, especially those that bring together family and friends and recall memories of joy and happiness.

Staff

Those sharing a crisis (complication, illness, or death) often become closely attached, so that the loss is felt not only by the family but also by the professional care providers. * Repeatedly dealing with death and deformity increases the professional’s exposure to personal feelings of grief and loss. This may be perceived either as a threat or a personal opportunity for growth. 37

The critical variable in the ability to face or assist others in handling loss is the manner in which the care providers have been able to resolve their own personal losses. Unless the care providers can cope with personal feelings of loss and grief, they may not be able to give of the “self” to others. Care given without genuine involvement and responsiveness to the family’s feelings does not facilitate and may actually impede the mourning process. Professionals who can deal honestly with their own feelings will be able to help others cope with theirs. 21,83

Helping parents deal with their grief may be difficult for professionals because of their attitudes and feelings about perinatal loss. For professionals trained to preserve life, loss of the best pregnancy outcome or death itself represents both a personal and professional failure. 58 When success is equated with life, the failure of death (or loss) is associated with feelings of guilt, anger, depression, and hostility. 128 Just when professionals are expected to be supportive and therapeutic, they may be overwhelmed with their own feelings. Professionally, the care providers may feel helpless when all efforts inevitably result in no change in the outcome.

The feelings and stages of grief experienced by the family are the same ones felt by the staff who are attached to the parents and their newborn. Many professionals working in perinatal care are of childbearing age, so identifying with the parents and their plight is relatively easy. Because the sick, deformed, or dead infant could easily be that of the staff, they share with the parents the special stress of the loss of a child. The care provider often experiences the same fantasies of blame as the parents: “What did I do (or not do) to cause this?”

Repetitive contact with loss situations and death exposes the staff to recurring feelings of frustration, guilt, self-doubt, depression, anger, classic grief reactions, helplessness, sadness, hopelessness, loneliness, and covert relief. 32 Such uncomfortable feelings often lead to behaviors of avoidance and withdrawal as a means of self-protection; this has been called “compassion fatigue.”21,83,96 Adequate medical care may be given, but psychologic care of the family may be neglected. 64 The involved primary care providers may decrease their attachment to both parents and infant when an unfavorable outcome is inevitable. Withdrawing emotional support and involvement may spare the professional but only adds to parental feelings of isolation, inadequacy, and worthlessness. Professionals who have risked family attachment and shared grief work may be more cautious in future involvements to protect themselves from the pain of loss.

Asynchrony and individual differences in handling grief reactions also may cause problems among the professional staff. Constant exposure to perinatal loss may desensitize some individuals until they are blasé or even callous about the crisis, whereas the grief reactions of others parallel the family’s reaction. Some staff members may have reached the stage of acceptance, whereas others who cannot let the infant go persist in the idea of a magical cure, a characteristic of denial. The rationale of prolonging the child’s life may in reality be prolonging death, and inevitably one needs to accept death’s finality.

Staff members cannot offer support to families experiencing loss unless they receive support in dealing with their own grief reactions. 21,37,39 Those who receive support learn about their feelings and how to handle them and so have no need to displace their pain to others. The three most effective ways that neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) nurses have identified to manage their stress after a neonate’s death are (1) discussing with co-workers, (2) supporting and comforting the grieving family, and (3) talking with their own families. 32 Various formats are available for meeting staff needs, such as mutual support of colleagues or group sessions involving peer counseling on a long-term or short-term basis. 21,32,39,58,92 Group meetings provide a vehicle for support and for sharing information and feelings among staff members. 21,32,39,58,92 Facilitated by an objective person with expertise in group process and the concepts of grief, such meetings have the goal of helping the staff deal with their reactions so they will be better equipped to help the parents. Group sessions also serve to decrease stress, increase job satisfaction, and ultimately help prevent burnout. Staff members are encouraged to retain their humanity when an environment is created in which emotions are valued and their healthy expression facilitated, both at the time of loss and in its resolution. 53,92

Sharing grief work with a family gives the care provider a chance for personal growth, to review past personal losses, and to evaluate the adequacy of their resolution. Helping others with loss or grief provides the professional with the opportunity to contemplate present and future losses, including one’s own mortality. By working with those who have suffered a significant loss or death, a health care provider may gain a deeper perspective about life.

INTERVENTIONS

Those in a crisis feel an openness to help and assistance from others, so that those in the crisis emerge either stronger or weaker, depending on the help they receive. 17,89 This increased openness also makes those in a crisis more vulnerable to the reactions of others—to their facial expression, tone of voice, and choice of words. Helpful professional interventions provide psychologic assistance during a highly vulnerable period of personal development. The goals of intervention are to maintain the pre-crisis level of functioning and to improve coping and problem-solving skills beyond the pre-crisis level (i.e., to facilitate personal growth). Effective intervention is characterized by helping grief work get started, by supporting those who are grieving adaptively, and by intervening with individuals who display maladaptive reactions. 22,35

For professionals, understanding parental perspectives of the experience of death of a newborn should enable provision of more sensitive and evidence-based care for grieving families. The results of two recent research studies give some insight into what is helpful and what is not helpful for grieving families. The first study was a systematic review of 61 studies and more than 6000 parents who suffered neonatal death. 43 This study found that parents valued emotional support, grief education, and attention to mother/baby. Non-helpful and distressing behaviors from health care providers included avoidance, thoughtlessness, insensitivity, and poor staff communication. 43 Another study conducted semi-structured interviews with mothers/fathers (n = 19) a mean of 1.9 years after death of their infant. This exploratory study found a low level of grief, effective coping, and factors important to parents in end-of-life care for their infant. 14 Review of the data from this study in Table 30-1 instructs health care professionals in helpful and non-helpful interventions during the stressful experience of a dying infant. 19 Because 76% of the dying infants were in the NICU or pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) and 42% of the families had hospice/palliative care team involvement, 14 perhaps the low level of grief and the positive adaptation by this small group of parents were because of the sensitive, helpful interventions of their health care providers.

| Study Findings | Comments |

|---|---|

| 1. Parents scored significantly lower than other parents who had lost a child and other adults with grief experience. | 1. Lower levels of grief were measured by the Revised Grief Experience Inventory (RGEI), a 22-item Likert scale. |

| 2. Study investigators viewed parents as positively adapting after loss of their infant. | 2. Mean scores were 33.16 (out of a highest possible score of 36) on the Post-Death Adaptation Score, a 10-item scale rated by professionals. |

| 3. Seven important aspects of care:

A. Honesty

B. Empowered decision making

C. Parental care

D. Environment

E. Faith/trust in nursing care

F. Physicians bearing witness

G. Support from other hospital care providers

|

3. Identified by parents:

A. Parents expect professionals to be honest in giving information about the infant/condition to them.

Parental anger results when (parental) perception is that honest information was not given.

B. Parents want to be involved in medical decision making, especially about withdrawing life support. Parents who had been involved were glad they had been part of the decision process and felt supported by the medical team.

Parents felt anger and abandonment when the decision to withdraw support was not believed to be respected by professionals.

C. Parents needed care as much as their baby; when staff were insensitive to their needs, parents felt upset.

D. Parents appreciated comforts of sleep/family rooms as well as private, quiet areas where the infant died with family/parents. People present at the death were more important than the place of death.

Parents expressed fear when left at home with their dying infant; parents wished they had held the infant longer.

E. Parents had greater trust in nurses than other providers; most had positive experiences with their infant’s nurses. Parents appreciated nurses personalizing and respecting the infant (using baby’s name) as well as providing for the infant’s comfort and opportunities for parental care of their baby.

Negative experiences included mistakes in care and unprofessional behavior.

F. Parents thought it important that the physician be with them throughout the process, including being present at the time of the infant’s death. Parents perceived the absence of the physician at the time of the child’s death as negative, especially if they had been told that the physician would be there for them.

Parents found it meaningful when the physician and other medical staff had contact with them after they had gone home.

G. Parents appreciated support that they received from chaplains, social workers, and palliative care and child life workers. Parents also appreciated support and help from these providers in dealing with siblings.

|

| 4. Seven coping strategies:

A. Family support

B. Keeping the memory alive

C. Spirituality/faith

D. Altruism

E. Refocusing on life

F. Validation of decision

G. Bereavement support groups

|

4. Identified by parents:

A. Parents relied on family support to cope with the death, appreciated family presence at the hospital/home when the infant died, and found it helpful to talk to extended family about their infant. When extended family members were not supportive and avoided talking about the infant, parents were distressed.

B. All parents showed researchers mementoes of their dead infant and emphasized the importance of bringing things home (i.e., photos; plaster castings of hands/feet; blanket/clothes) from the hospital that had been used/belonged to the infant who died. Parents especially appreciated tangible reminders (i.e., garden/tree) and rituals to remember their infant.

C. All families were comforted by their religious beliefs and found meaning and purpose in their infant’s life and death. No families reported negative spiritual experience or abandonment of their religious beliefs.

D. Many parents wanted and did “give back” to the hospitals that had cared for them and their dying infants. These altruistic acts took the form of monetary and equipment donations, volunteering, and becoming resource families to other parents with sick children.

E. Presence of other children in the family assisted parents continuing to focus on life and the daily requirements of their surviving children. All parents acknowledged that having another child would never replace the infant who died.

F. Parents were comforted by autopsy results that validated that they had made the correct decision for their infant. Parents also appreciated when physicians communicated to them their support of the parents’ decision.

G. Bereavement support groups resulted in positive experiences for most families, especially in being able to talk freely about their dead infant with others who understood and were not uncomfortable. However, some parents did not feel validated in their grief/loss of an infant by other parents in the group whose children were “older” when they died.

|

Non-helpful Interventions

Caring for pregnant women and their infants is supposed to be a “happy” job. Birthing and caring for infants are supposed to be times of joy and celebration. Because no one expects death or loss to occur in maternity or nursery areas, when it does, both staff and families are shocked. To protect themselves from the reality of the situation or to “spare” the family, professionals may engage in interventions that do not help themselves or their patients. Such interventions may be meant altruistically but do not have the characteristics of effective intervention.

Maintaining the state of denial arrests grief work by preventing or delaying the acceptance of the reality of the loss situation. Progress toward resolution is not begun until the stage of disbelief is relinquished. Using drugs, not talking or crying about the loss, and using distraction all contribute to maladaptive reactions by maintaining the state of denial. The use of tranquilizers, sedatives, and other drugs does not help the recipient but, rather, benefits the giver. Excessive use of these medications prolongs the denial stage by making the feelings and emotions foggy and dreamlike. 56 The energy needed to begin the grief work is dissipated by the effect of the medications. Avoiding the reality of the situation becomes easier when mind-altering drugs make the tragedy even more unbelievable.

Not talking about the loss is a powerful way of denying that it ever existed. 83,93 The inability of professionals to acknowledge that the loss has occurred and that the family is in pain maintains denial and repression. 16 Not discussing the loss prevents parents from learning the facts and facing their reality. Because a fantasy will be created to substitute for the unknown, the fantasy of what happened and why will be worse than the reality. By receiving truthful, honest communication, parents are not left to spend energy dealing with frightening fantasies.

Professional avoidance and unwillingness to talk with parents after a loss communicate other powerful messages that impede grief work. If the loss is not important enough to discuss, then perhaps it is not important at all. Not talking about the loss serves to reduce it and communicates to the parents, “I don’t care; therefore neither should you.” Avoidance of the topic or a hurried, businesslike or social communication that skirts the issue tells the parent that grief work is dangerous, that grief emotions are dangerous, and that others are afraid of grief and those experiencing it. In essence, not discussing the loss gives a clear nonverbal message to not grieve.

An inability to cry in response to a significant loss is not helpful and impedes grief work. The prohibition against crying may have been learned early in life or may be the result of unresolved grief work. Parents may feel the need to be strong for each other, their family, or the staff and thus do not cry. Sometimes role reversal occurs, so that the grieving person feels the need to support others rather than be the recipient of support. Often the significance of parental loss is neither recognized nor acknowledged by the professional for fear that he or she will cry. Rather than talking about the loss as a technique to facilitate tears, no one says anything so no one will cry, and no one’s grief progresses through the grief stages.

Distraction is another way of denying the loss or its significance. Professionals, a spouse, or other family members try to distract parents from the feelings and emotions of acute grief by engaging in light, social conversation or by keeping them busy with work or recreation. Dealing only with the physical care and not the need for psychologic care after birth is a form of distraction used by care providers. 47 Parents are preoccupied with their shattered expectations of the past and the stark reality of the present, and they are not interested in distractions.

After an unfavorable perinatal outcome, the couple are often confused about their status: “Am I a mother or father…or not?” This experience has been called the “ambivalent transition into motherhood.”65 Failure to acknowledge the newly acquired role of mother or father (even if the fetus or newborn dies) discounts the parent’s psychologic investment in the pregnancy, fetus, and newborn. Quickly removing the infant from the maternity or nursery areas or removing all the baby items from the home negates the infant’s existence. 58 This is not helpful for grief resolution and prevents parents from making choices and decisions and thus maintaining control over the reality of the situation.

Isolation of the grieving family prevents the development of dependent relationships with others who might potentially provide support and comfort. Without others, parents cannot share their grief and may thus increase their feelings of guilt, anger, blame, and lack of self-worth at their failed pregnancy. Those directly experiencing a perinatal loss may be isolated from the rest of society, including their families, who do not view loss of a pregnancy or neonate as significant. 10,58,93 Empathy with the parents’ definition of the loss as important is necessary for society to be supportive. The goal of recent research, professional literature, and education has been to sensitize the care provider to the effect of perinatal loss. Only recently have books specifically about perinatal loss become available to inform and assist parents.

To decrease contact with the grieving mother, the staff may neglect her or perform cursory physical care, or there may be overconcern for providing physical care. 71 Assigning a room at the end of the hall, not going into the room, delaying answering requests, and placing the mother on another floor are ways of avoiding families. Use of private rooms and room assignments off the maternity floor may be helpful but may allow staff to remove the unpleasant and uncomfortable situation. Early discharge to a supportive environment may be helpful but, without plans for follow-up, may merely be a way to remove the constant, painful reminder.

Keeping the childbearing couple together throughout the perinatal events facilitates a shared experience of the reality of the situation. Separation of the mother and father or of the couple from friends, family, and other children is not helpful. Exclusion of family members from the experience also excludes them from providing support for the mother and the couple. Relaxed visiting policies and as much contact as possible between the hospitalized mother and the father (and other family members) are important. 20,83

Prohibiting contact between the parents and the infant allows fearful fantasies of the truth that are always more frightening than the reality of the situation. Delayed contact prolongs the state of disbelief and denial. 22 Restrictive visiting policies in the nursery, institutionalizing an infant without looking at all alternatives, or any other policy that separates parents from their infant does not facilitate grief. Especially in the case of a deformed, stillborn, or dead infant, the message of delayed or no contact is that the infant is too horrible and too unacceptable to be seen or touched. Because parental egos are so symbiotically attached to their offspring, an unacceptable child is equated with an unacceptable and unworthy self. The fantasy that the damaged or dead child is representative of the damaged and defective self is borne out in the behavior and separation policies of the care providers.

In an attempt to offer the grieving family comfort, friends, relatives, and even professionals often make comments that are non-supportive and non-helpful58,83:

• “Well, you’re young. You can have more babies.”

• “Just have another baby right away.”

• “Well, at least you have others at home.”

• “It’s better to lose her now when she’s a baby than when she’s 4 years old.”

• “He never would have been totally normal anyway.”

• “He was born dead. You didn’t get a chance to know or get attached to him anyway.”

• “It’s God’s will.”

Clichés and platitudes such as these do not help because of the message they give about the parents and the infant. 99 These comments at best reduce and at worst negate the effect of prenatal attachment to the fetus. The importance of psychologic investment and attachment by the parents to this fetus or newborn is said to be basically unimportant and essentially nonexistent. 58 Because infants are viewed as an extension of the parent’s self, “by a not very subtle process of identification, the parents see a part of themselves in the baby, and nobody likes to be told that part of them is better off dead.”99 Also, comforting parents whose infant has died with the information that the child was not perfect and never would have been normal and healthy reinforces their belief that they are as defective and unsatisfactory as their dead child. 58

Such comments also convey a message about the importance of an individual life. Essentially, they say that one fetus or newborn is fairly interchangeable with another. They negate the importance of and indeed the existence of the infant for the parents, siblings, family, and society. The life of the individual is devalued, because he or she is easily replaced by “another baby.” Comparing one infant’s illness or deformity with another’s is not helpful for parents whose own infant’s deformity is certainly more important than any other infant’s problem.

The power of words to help during grief is outweighed only by their power to not help. Because parents are increasingly open during a perinatal crisis, they are sensitive not only to what is said and how it is said but also to the nonverbal message. Giving premature or false reassurance may be more for relief of the professionals than for the parents. 17 Comments such as “It’s okay” and “Everything will be all right” must be genuine and timed appropriately for the parent. Telling parents that they have a child with Down syndrome and then saying “But everything will be all right” is hardly helpful. Giving reassurance that subsequent pregnancies and infants will be all right or unaffected is not helpful before the parents are ready to think about and project into the future.

The basic terminology accompanying perinatal grief situations may be upsetting to parents. Instead of dead, professionals often substitute less frightening and less final words. The use of loss when death is appropriate may be misinterpreted (especially by children). The terms lose, loss, and lost connote misplacing, so that comments such as “I’m sorry you lost your baby” may be responded to by “I didn’t lose (misplace) my baby. My child died.” Medical professionals skirt the use of the words dead, died, and die. Care providers are taught as students to use the word expired when referring to a patient who has died. Meant to soften the effect of dead, the word expired may have its own effect, as a mother whose infant son died wrote in a poem: “The baby expired they said, as if you were a credit card.”113

Other situations that do not facilitate grief work include dealing with multiple losses or stresses and ambivalence or mental illness. 128 The reaction to the loss of a significant relationship is intensified in the context of multiple losses, stresses, and problems. 83,128 Because perinatal losses represent not only a loss of the wished-for perfect child but also a threat to the parental self, self-concept, and self-worth, they represent situations of multiple loss. 119,120

Helpful Interventions

Professionals have an opportunity to make a significant difference in the outcome after the crisis of perinatal loss for the individual, the couple, and the family. A care provider who is knowledgeable about the grief process and comfortable in sharing another’s grief is equipped to assist the family and its members toward a long-term healthy adjustment rather than a dysfunctional and pathologic adjustment. Interventions that are helpful for family members also assist staff members in their own grief work.

Factors that influence an individual’s personal experience of grief (and ultimately appropriate interventions) are outlined in Box 30-2. Care for the grieving is individualized through assessing these factors, planning, and continually evaluating the individual. 34,35,83,96 Eliciting such personal information may not be as difficult as it first seems. Those in crisis often spontaneously share crucial data with little prompting. The importance of active listening to questions and comments or a more formalized therapeutic interview process may provide the needed encouragement and permission to begin communication.

BOX 30-2

1. Previous losses

a. Type

Separation

Divorce

Death

Spontaneous abortion (miscarriage)

Elective or selective abortion

Period of infertility

Relinquishment of child

Perinatal loss

b. Timing in the life cycle

Distant

Recent

c. Coping styles (of each individual and the family as a unit)

d. Grief work

Resolved

Unresolved

2. Prenatal attachment

a. Degree of psychologic investment in relationship with fetus or newborn

b. Decision making about pregnancy and infant

Planned or unplanned

Wanted or unwanted

c. Meaning of pregnancy and infant to individual and family

d. Parental expectation about childbearing

3. Nature of the current loss

a. Timing

Sudden and expected

Anticipatory grief

b. Definition and meaning of the event (death, deformity) to individual members of the family

c. Multiple losses

Self

Perfect child

d. Nature and severity

Of loss

Of defect

4. Cultural influences (also see Chapter 29)

a. On experience and the expression of grief

b. Societal expectations dictate acceptable and unacceptable behaviors of mourning

5. Strengths (individual and family)

a. Support system (family, friends, religious, community, or social agencies) mobilized when necessary

b. Stable relationships: couple supportive of each other

c. Financial stability

d. Coping abilities: can evaluate, plan for, and adjust to novel situations

e. Good health

f. Receptive and intelligent

g. Realistic expectations about childbearing and childrearing

A history of previous losses and their type and timing in the life cycle are important data for the care provider dealing with the current loss. Past experiences with a crisis or loss influence an individual’s behavioral and coping style with current problems. 121 Experiencing a previous perinatal loss affects a subsequent pregnancy. 24,95 These pregnancies are characterized by guarded emotions, marking the progress of the pregnancy and seeking out or avoiding various behaviors. 23.24.25. and 26.121 A previous perinatal loss may compound the individual’s reaction to a current loss. Dealing with problems alone, receiving help and support from others, and withdrawing altogether are possible ways of coping with the loss.

The degree of attachment and the meaning of the pregnancy and impending parenthood to the family define expectations and influence reactions if an optimal outcome does not occur. The experience of grief depends on whether the loss situation was sudden and unexpected or if there was forewarning about a problem or complication. The definition and meaning of the crisis (e.g., the nature and severity of a deformity, the finality of death, or the chronic sorrow of a defective infant) reflect the individual’s and family’s value system and previous crisis experience. The process of grief is affected by the event itself, the previous and current coping mechanisms, and the family’s definition of the event. Consideration of all of these factors is crucial in instituting appropriate intervention.

Cultural practices among families and professionals often differ (see Chapter 29). 94 For example, in some cultures, it may not be acceptable to see or hold your baby (as in some Native American cultures). In the Muslim culture, the family is the primary system of support and it is rare to see a Muslim family emote publicly. It is critical for health care practitioners to recognize cultural and religious differences to minimize misinterpretations and conflicts with families. With increasing immigration, practitioners must be able to respond with a more ethnic-sensitive approach. 20,35,63,77,104 It is essential to be creative and flexible, thus respecting families’ cultural and religious belief systems. 2,117,125 Studies show that cultural differences influence (1) parental emotional response to and perception of their infant’s illness and disability, (2) parental utilization of services, (3) parental interactions with health care providers, and (4) the ceremonies and rituals surrounding death. 11,35,63

The national association Share: Pregnancy & Infant Loss Support, Inc. has revised the “Rights of Parents When a Baby Dies” and “Rights of the Infant” (Box 30-3). These documents serve as guidelines for creation of protocols, checklists, and bereavement programs; affirmation and empowering tools for bereaved parents; and communication points for parents and care providers initiating the grief process. 85

BOX 30-3

Rights of Parents

1. To be given the opportunity to see, hold, and touch their baby at any time before or after death, within reason

2. To have photographs of their baby taken and made available to the parents or held in security until the parents want to see them

3. To be given as many mementos as possible (i.e., crib card, baby beads or bracelet, ultrasound or other photographs, lock of hair, feet and hand prints, and record of weight and length)

4. To name their child and bond with him or her

5. To observe cultural and religious practices

6. To be cared for by an empathetic staff who will respect their feelings, thoughts, beliefs, and individual requests

7. To be with each other throughout hospitalization as much as possible

8. To be given time alone with their baby, allowing for individual needs

9. To be informed about the grieving process

10. To request an autopsy; in the case of a miscarriage, to request to have or not have an autopsy or pathology examination as determined by applicable law

11. To plan a farewell ritual, burial, or cremation in compliance with local and state regulations and according to their personal beliefs, religion, or cultural tradition

12. To be provided information on support resources that assist in the healing process (i.e., support groups, counseling, reading material, and perinatal loss newsletter)

Rights of the Infant

1. To be recognized as someone who was born and died

2. To be named

3. To be seen, touched, and held by the family

4. To have life-ending acknowledged

5. To be put to rest with dignity

Modified from SHARE pregnancy and infant loss support, Available at www.nationalshareoffice.org.

ENVIRONMENT

The first step in facilitating grief work is to create an environment that is supportive, permissive, and conducive to the expression of feelings. 16,21,83,93 This type of environment does not depend on physical surroundings but, rather, is created and maintained by a warm, receptive, accepting, and caring staff. Such an environment centers its concern more on the people giving and receiving care than on the tasks of care. 58 This type of environment is nonjudgmental and is characterized by an attitude of openness and freedom. 19,99 People feel safe enough to ventilate a full range of feelings—sadness, anger, despair, and even humor—without the fear of condemnation or rejection. The staff become role models of open communication, facing grief, and feeling comfortable in an uncomfortable situation. The safety of such an environment generates feelings of acceptance and understanding so that grieving and healing may proceed.

Professional presence and support are essential to families in crisis because of the increased dependency needs that accompany grief and loss. Yet certain aspects of a conducive environment such as privacy, quiet, and comfort may be difficult to obtain in a noisy and busy perinatal setting. The recommendation to never leave the family alone must be balanced with their need for privacy and personal time alone with their infant (stillborn, ill, or dying). Simply saying “I will stay with you unless you ask me to leave so that you can have some private time alone with your child” or “Would you like me to leave for a while so that you can be alone with your baby?” offers both support and privacy. Many parents later regret not having time alone and not thinking to ask to be alone with their infant.

A quiet place away from the hustle and bustle of the routine may facilitate both attachment and detachment. The mother of a stillborn child who is quickly shown her infant in the delivery room as her episiotomy is being repaired is not in an optimal physical (or psychologic) environment. Attaching to and saying good-bye to her infant are better accomplished in a quieter and more private setting with significant others present. 64,82,110 Active participation of parents at the death of their newborn may not optimally occur in a busy intensive care unit. Rather, adaptation of hospice concepts to neonatal care provides a private, homelike room, with focus on palliative (comfort) care, rather than cure, to the dying newborn and the family (see Chapter 32). 21,96,107,108 When the family is too emotionally drained, they may elect to “say good-bye” and leave the hospital before life support is removed; the nurse then disconnects, holds, and rocks the baby so the infant does not die alone. 15,83 In some situations (e.g., chromosomal anomalies), parents and professionals may opt to provide end-of-life care ideally with hospice care at home. 74

Supportive, Trusting Relationships