Granulomatous and histiocytic diseases

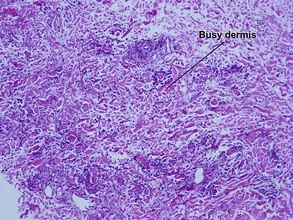

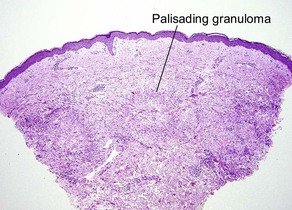

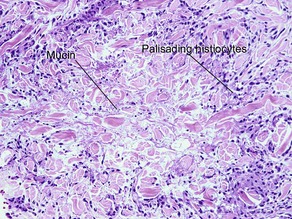

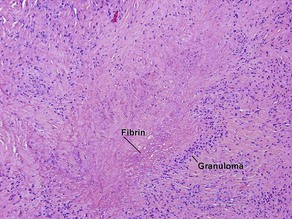

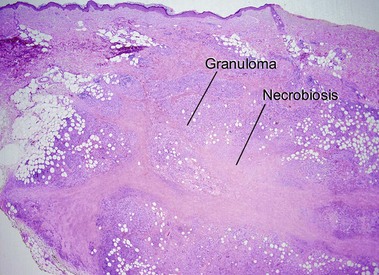

Granuloma annulare

Table 10.1 shows distinctions between granuloma annulare and necrobiosis lipoidica.

Table 10-1

Features of granuloma annulare and necrobiosis lipoidica

| Feature | Granuloma annulare | Necrobiosis lipoidica |

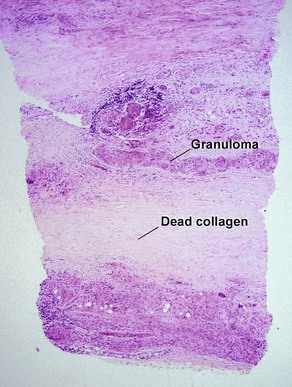

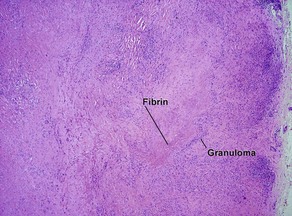

| Distribution | Focal and patchy | Diffuse and full-thickness |

| Granuloma | Palisaded or interstitial | Horizontal tiers (layers) |

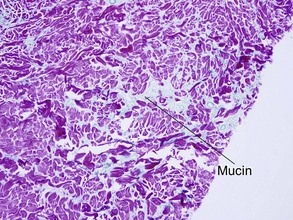

| Mucin | Yes | No |

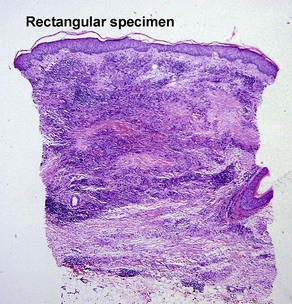

| Shape of punch biopsy | Tapered | Rectangular |

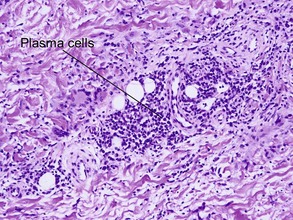

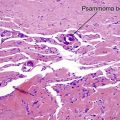

| Plasma cells | Rare | Common |

| Cholesterol clefts | No | Occasional |

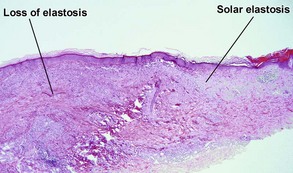

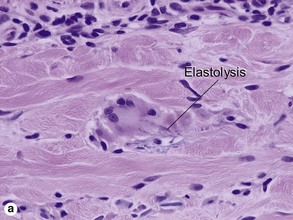

Actinic granuloma

These lesions occur on areas of chronic sun damage such as the face, neck, hands, and arms. They have a raised border and atrophic finely wrinkled center. The granulomas consume actinically damaged elastic tissue. Other names have included Miescher’s facial granuloma, atypical necrobiosis lipoidica of the face and scalp, and annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Some consider it to be a variant of granuloma annulare on sun-damaged skin. The central loss of elastic tissue, absence of mucin, and conspicuous multinucleated histiocytes are the primary basis for distinguishing these lesions.

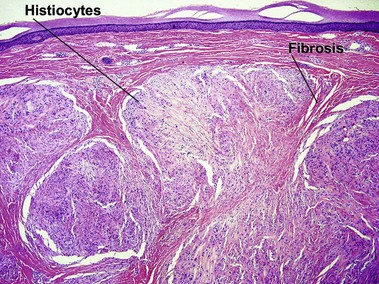

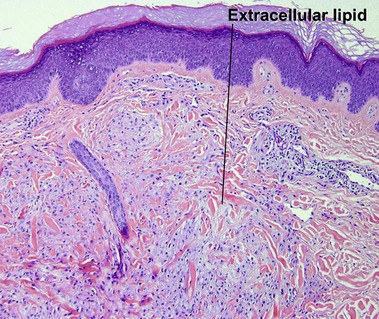

Necrobiosis lipoidica

A large proportion of patients with necrobiosis lipoidica have diabetes, thus the original name necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum. However, fewer than 1% of patients with diabetes have necrobiosis lipoidica. The pretibial area is the most common site but other areas of the lower extremities, arms, hands, and trunk can rarely be involved.

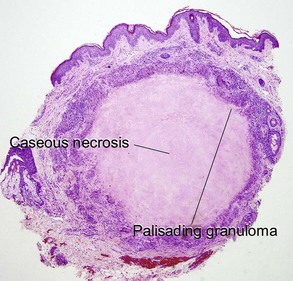

Rheumatoid nodule

The histology mimics subcutaneous granuloma annulare and rheumatic fever nodules. Rarely similar nodules occur in systemic lupus erythematosus.

Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei (LMDF: acne agminata)

Despite its histologic resemblance to miliary tuberculosis, LMDF is a variant of rosacea. LMDF can be distinguished from miliary tuberculosis by the absence of acid-fast bacilli.

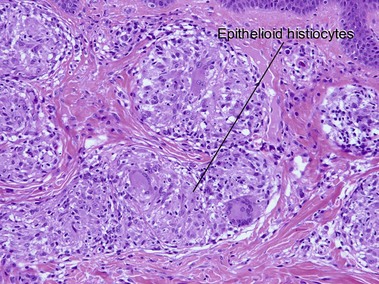

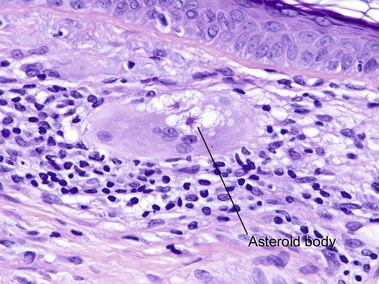

Sarcoidosis

Cutaneous lesions are present in up to one-quarter of patients with systemic sarcoidosis, but cutaneous lesions can occur in the absence of systemic disease in one-quarter of patients.

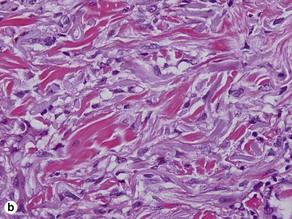

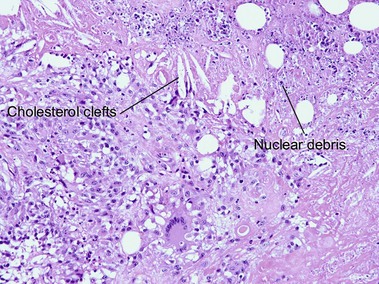

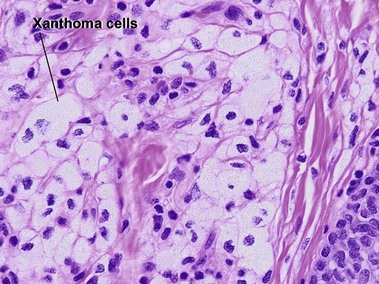

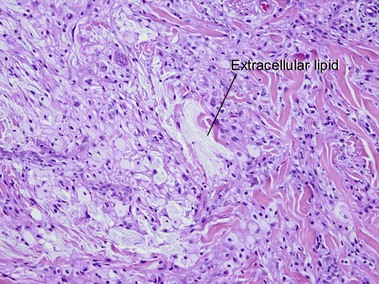

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma

If the layered appearance of necrobiosis lipoidica is likened to strips of bacon, then the appearance of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma resembles “pepper bacon” or “dirty cholesterol-laden bacon,” with karyorrhectic debris making up the “pepper” or “dirt.” The differentiation from necrobiosis lipoidica can be made clinically by the periorbital predominance and associated immunoglobulin (Ig) G (usually kappa) paraproteinemia in necrobiotic xanthogranuloma. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is more cellular, has a greater proportion of foamy histiocytes, and contains more giant cells than necrobiosis lipoidica.

Xanthogranuloma

Xanthogranulomas can be seen at any age but are most common in children, giving rise to the name juvenile xanthogranulomas.

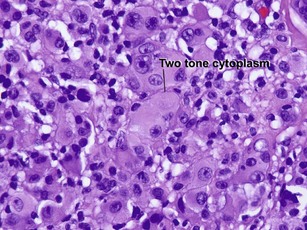

Reticulohistiocytic granuloma (solitary reticulohistiocytoma)

Multinucleate cells typically have irregularly arranged vesicular nuclei containing prominent nucleoli. There are admixed lymphocytes and lesser numbers of eosinophils and neutrophils. Older lesions are less inflammatory and reveal cells with artifactual halos around them due to retraction.

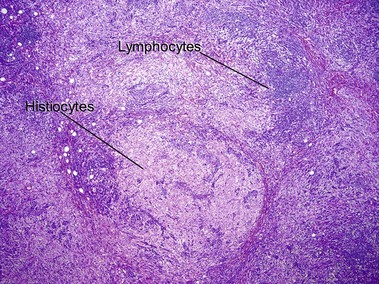

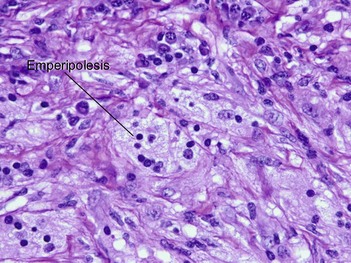

Rosai–Dorfman disease (sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy)

Rosai–Dorfman disease typically occurs in the first two decades of life as painless cervical adenopathy and fever. There is extranodal involvement in one-third of cases. Skin lesions are found in approximately 10% with a predilection for the eyelids and the malar area. Occasionally, the skin is the only site of involvement. Emperipolesis is a phenomenon where lymphocytes and plasma cells pass through histiocytes, but are not found within phagolysosomes.

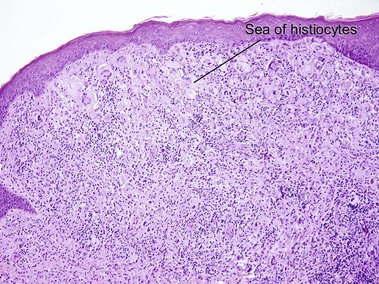

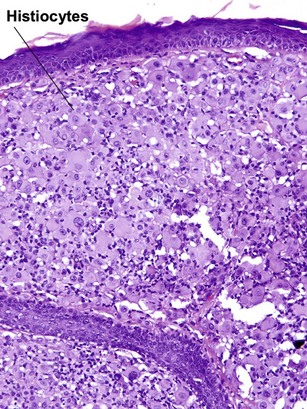

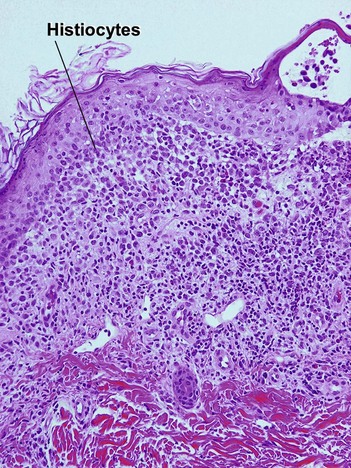

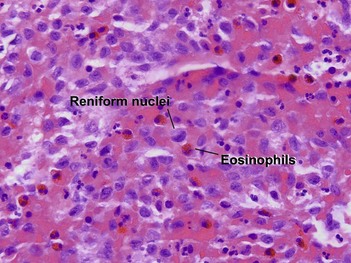

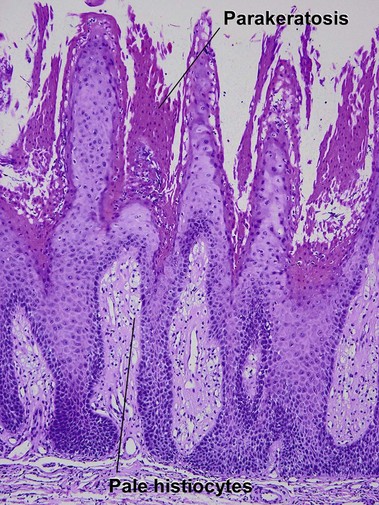

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (histiocytosis X)

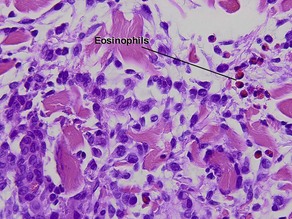

The infiltrate can be a perivascular, band-like, or periappendageal pattern. Variable eosinophils, lymphocytes, and sparse neutrophils accompany the characteristic large cells with lobulated, notched, or grooved nuclei that resemble kidney beans. Due to the edema, these cells appear to be “floating in the sea.” Acute Langerhans cell histiocytosis is described in further detail in Chapter 15.

Xanthomas

Xanthelasma

Xanthelasma are the most common form of xanthoma and are characterized by periorbital yellowish plaques. Lipid levels are normal in around half of patients.

Tuberous xanthoma

Tuberous xanthomas are typically seen on the elbows, knees, and buttock, in cases with an increase in chylomicron and very-low-density lipoprotein remnants. These lesions are most characteristic of familial dysbetalipoproteinemia (type II), but can also be seen in homozygous and heterozygous hypercholesterolemia, hepatic cholestasis, cerebrotendinous xanthoma, and ß-sitosterolemia.

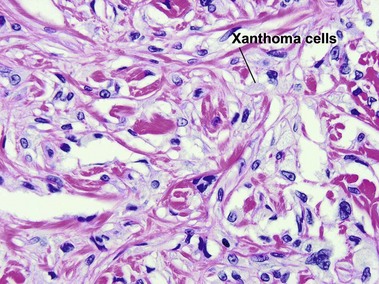

Eruptive xanthoma

The lipid deposition in the dermis is so rapid in eruptive lesions that the phagocytic capacity of the histiocytes is overwhelmed, resulting in free or extracellular lipid.

Beatty, EC, Jr. Rheumatic-like nodules occurring in nonrheumatic children. AMA Arch Pathol. 1959; 68(2):154–159.

de Oliveira, FL, de Barros Silveira, LK, Machado Ade, M, et al. Hybrid clinical and histopathological pattern in annular lesions: an overlap between annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma and granuloma annulare? Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2012; 102915.

Eisen, RN, Buckley, PJ, Rosai, J. Immunophenotypic characterization of sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai–Dorfman disease). Semin Diagn Pathol. 1990; 7(1):74–82.

el Darouti, M, Zaher, H. Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei – pathologic study of early, fully developed, and late lesions. Int J Dermatol. 1993; 32(7):508–511.

Finan, MC, Winkelmann, RK. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma with paraproteinemia. A review of 22 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 1986; 65(6):376–388.

Hanke, CW, Bailin, PL, Roenigk, HH, Jr. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. A clinicopathologic study of five cases and a review of similar entities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1979; 1(5):413–421.

Hanno, R, Needelman, A, Eiferman, RA, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidal granulomas and the development of systemic sarcoidosis. Arch Dermatol. 1981; 117(4):203–207.

Helm, KF, Lookingbill, DP, Marks, JG, Jr. A clinical and pathologic study of histiocytosis X in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993; 29(2 Pt 1):166–170.

Mehregan, AH, Altman, J. Miescher’s granuloma of the face. A variant of the necrobiosis lipoidica–granuloma annulare spectrum. Arch Dermatol. 1973; 107(1):62–64.

Mohsin, SK, Lee, MW, Amin, MB, et al. Cutaneous verruciform xanthoma: a report of five cases investigating the etiology and nature of xanthomatous cells. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998; 22(4):479–487.

O’Brien, JP. Actinic granuloma. An annular connective tissue disorder affecting sun- and heat-damaged (elastotic) skin. Arch Dermatol. 1975; 111(4):460–466.

Silverman, RA, Rabinowitz, AD. Eosinophils in the cellular infiltrate of granuloma annulare. J Cutan Pathol. 1985; 12(1):13–17.

Walsh, NM, Hanly, JG, Tremaine, R, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis and foreign bodies. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993; 15(3):203–207.