Chapter 7 Global Developmental Delay and Regression

Developmental delay occurs in approximately 1% to 3% of children. Since developmental delay is common, monitoring a child’s development is an essential component of well-child care. Ongoing assessment of the child’s development at each well-child visit creates a pattern of development that is more useful than measuring the discrete milestone achievements at a single visit; therefore, developmental screening should be completed at each well-child visit (Council on Children with Disabilities, 2006). Identification of a child with developmental delays should be accomplished as early as possible, because the earlier a child is identified, the sooner the child can receive a thorough evaluation and begin therapeutic interventions that can improve the child’s outcome. Developmental delay is common and one of the most frequent presenting complaints to a pediatric neurology clinic; neurologists should have a systematic approach to the child with developmental delay.

Typical and Atypical Development

Child Development Concepts

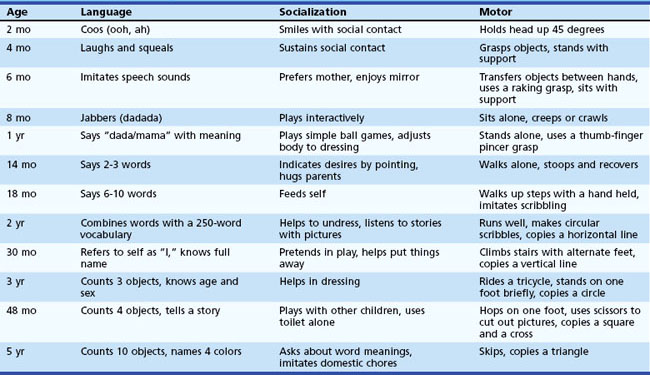

On average, most children achieve each developmental milestone within a defined and narrow age range (Table 7.1). Usually physicians learn the average age for acquiring specific skills. However, since each developmental skill can be acquired within an age range, it is much more useful clinically to know when a child’s development falls outside this range. These so-called red flags are important because they can be used to identify when a child has developmental delay for specific skills. For example, although the average age of walking is approximately 13 months, a child may walk as late as 17 months and still be within the typical developmental range. In this example, the red flag for independent walking is 18 months, and a child who is not walking by 18 months of age is delayed.

Global Developmental Delay

Neurological and Other Medical History

For children with global developmental delay, the clinician should obtain a thorough medical history, including a detailed neurological history. Pertinent aspects of the history include the presence of any other neurological condition such as epilepsy, vision or hearing impairments, ataxia or a movement disorder, sleep impairment, and behavioral problems. The clinician should also inquire about prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal factors that can impact a child’s development (Tables 7.2 and 7.3). The social history should probe for environmental factors that can affect development, including physical or other forms of abuse, neglect, psychosocial deprivation, family illness, impaired personalities in family members, sociocultural stressors, and the economic status of the family.

| Prenatal/Perinatal | Examples |

|---|---|

| Congenital malformations of the CNS | Lissencephaly, holoprosencephaly |

| Chromosomal abnormalities | Down syndrome, Turner syndrome |

| Endogenous toxins | Maternal hepatic or renal failure |

| Exogenous toxins from maternal use | Anticonvulsants, anticoagulants, alcohol, drugs of abuse |

| Fetal infection | Congenital infections |

| Prematurity and/or fetal malnutrition | Periventricular leukomalacia |

| Perinatal trauma | Intracranial hemorrhage, spinal cord injury |

| Perinatal asphyxia | Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy |

| Postnatal | Examples |

| Inborn errors of metabolism | Aminoacidopathies, mitochondrial diseases |

| Abnormal storage of metabolites | Lysosomal storage diseases, glycogen storage diseases |

| Abnormal postnatal nutrition | Vitamin or calorie deficiency |

| Endogenous toxins | Hepatic failure, kernicterus |

| Exogenous toxins | Prescription drugs, illicit substances, heavy metals |

| Endocrine organ failure | Hypothyroidism, Addison disease |

| CNS infection | Meningitis, encephalitis |

| CNS trauma | Diffuse axonal injury, intracranial hemorrhage |

| Neoplasia | Tumor infiltration, radiation necrosis |

| Neurocutaneous syndromes | Neurofibromatosis, tuberous sclerosis complex |

| Neuromuscular disorders | Muscular dystrophy, myotonic dystrophy |

| Vascular conditions | Vasculitis, ischemic stroke, sinovenous thrombosis |

| Other | Epilepsy, mood disorders, schizophrenia |

CNS, Central nervous system.

From Sherr, E.H., Shevell, M.I., 2006. Mental retardation and global developmental delay, in: Swaiman, K.F., Ashwal, S., Ferriero, D.I. (Eds.), Pediatric Neurology, Principles and Practice, fifth ed. Mosby, Philadelphia.

Table 7.3 Perinatal Risk Factors for Neurologic Injury

| Maternal/Prenatal | Natal | Postnatal |

|---|---|---|

| Age <16 years or >40 years | Intrauterine hypoxia: prolapsed umbilical cord, abruptio placenta, circumvallate placenta | Abnormal feeding: poor sucking, weight gain, malnutrition, vomiting |

| Cervical or pelvic abnormalities | Midforceps delivery or breech presentation | Abnormal crying |

| Maternal illnesses: infection, shock, diabetes, nephritis, phlebitis, proteinuria, renal hypertension, thyroid disease, drug addiction, malnutrition | Poor Apgar scores: cyanosis, poor respiratory effort, bradycardia, poor reflexes, hypotonia | Abnormal exam: asymmetrical face, asymmetrical extremities, dysmorphic features, hypotonia, birth injuries, seizures |

| Maternal features: unmarried, uneducated, nonwhite, low-income, thin, short | Need for resuscitation: respiratory distress, bradycardia, hypotension | Abnormal findings: hyperbilirubinemia, fever, hypothermia, hypoxia |

| Consanguinity | Gestational age <30 weeks | |

| Prior abnormal pregnancy, miscarriages, stillbirths, abortions, neonatal deaths, infants less than 1500 g, abnormal placenta | Vaginal bleeding in the second or third trimester | |

| Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy | ||

| Polyhydramnios or oligohydramnios |

From Sherr, E.H., Shevell, M.I., 2006. Mental retardation and global developmental delay, in: Swaiman, K.F., Ashwal, S., Ferriero, D.I. (Eds.), Pediatric Neurology, Principles and Practice, fifth ed. Mosby, Philadelphia.

Physical Examination

A complete general physical and neurological examination should be performed to the extent the child will allow. The general examination should include but not be limited to an evaluation for dysmorphic features; abnormalities of the eyes (Table 7.4), skin, and hair; and organomegaly (Table 7.5). The neurological examination should include signs of impairment in extraocular movements; hypertonia or hypotonia; focal or generalized weakness; abnormal posture or movements; abnormal or asymmetrical tendon reflexes; ataxia, incoordination or other signs of cerebellar dysfunction; and gait abnormalities (see Table 7.5).

Table 7.4 Ocular Findings Associated with Selected Syndromic Developmental Disorders

| Finding | Examples |

|---|---|

| Cataracts | Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis, galactosemia, Lowe syndrome, LSD, Wilson disease |

| Chorioretinitis | Congenital infections |

| Corneal opacity | Cockayne syndrome, Lowe syndrome, LSD, xeroderma pigmentosa, Zellweger syndrome |

| Glaucoma | Lowe syndrome, mucopolysaccharidoses, Sturge-Weber syndrome, Zellweger syndrome |

| Lens dislocation | Homocystinuria, sulfite oxidase deficiency |

| Macular cherry-red spot | LSD, multiple sulfatase deficiency |

| Nystagmus | Aminoacidopathies, AT, CDG, Chédiak-Higashi syndrome, Friedreich ataxia, Leigh syndrome, Marinesco-Sjögren syndrome, metachromatic leukodystrophy, neuroaxonal dystrophy, Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease, SCD |

| Ophthalmoplegia | AT, Bassen-Kornzweig syndrome, LSDs, mitochondrial diseases |

| Optic atrophy | Alpers disease, Leber optic atrophy, leukodystrophies, LSDs, neuroaxonal dystrophy, SCD |

| Photophobia | Cockayne syndrome, Hartnup disease, homocystinuria |

| Retinitis pigmentosa or macular degeneration | AT, Bassen-Kornzweig syndrome, Cockayne syndrome, CDG, Hallervorden-Spatz syndrome, Laurence-Moon-Biedl syndrome, LSD, mitochondrial diseases, Refsum disease, Sjögren-Larsson syndrome, SCD |

AT, Ataxia-telangiectasia; CDG, congenital disorders of glycosylation; LSD, lysosomal storage diseases; SCD, spinocerebellar degeneration.

From Sherr, E.H., Shevell, M.I., 2006. Mental retardation and global developmental delay, in: Swaiman, K.F., Ashwal, S., Ferriero, D.I. (Eds.), Pediatric Neurology, Principles and Practice, fifth ed. Mosby, Philadelphia.

Table 7.5 Other Findings Associated with Selected Syndromic Developmental Disorders

| Finding | Examples |

|---|---|

| Cerebellar dysfunction | Aminoacidopathies, AT, Bassen-Kornzweig syndrome, CDG, cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis, Chédiak-Higashi syndrome, Cockayne syndrome, Friedreich ataxia, Lafora disease, LSD, Marinesco-Sjögren syndrome, mitochondrial disease, neuroaxonal dystrophy, Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease, Ramsay Hunt syndrome, SCD, Wilson disease |

| Hair abnormalities: | |

| Synophrys | Cornelia de Lange syndrome |

| Fine hair | Homocystinuria, hypothyroidism |

| Kinky hair | Argininosuccinic aciduria, Menkes disease |

| Hirsutism | LSD |

| Balding | Leigh syndrome, progeria |

| Gray hair | AT, Chédiak-Higashi syndrome, Cockayne syndrome, progeria |

| Hearing abnormalities: | |

| Hyperacusis | LSD, SSPE, sulfite oxidase deficiency |

| Conductive loss | Mucopolysaccharidoses |

| Sensorineural loss | Adrenoleukodystrophy, CHARGE, Cockayne syndrome, mitochondrial diseases, SCD, Refsum disease |

| Infantile hypotonia | Canavan disease, myopathies, LSD, Leigh syndrome, Menkes disease, neuroaxonal dystrophy, spinal muscular atrophy, Zellweger disease |

| Limb abnormalities: | |

| Micromelia | Cornelia de Lange syndrome |

| Broad thumbs | Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome |

| Macrocephaly | Alexander disease, Canavan histiocytosis X, LSD |

| Microcephaly | Alpers disease, CDG, Cockayne syndrome, incontinentia, pigmenti, neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses, Crabbe disease, neuroaxonal dystrophy, Rett syndrome |

| Movement disorders | AT, LSD, dystonia musculorum deformans, Hallervorden-Spatz, juvenile Huntington disease, juvenile Parkinson disease, Lesch-Nyhan disease, phenylketonuria, Wilson disease, xeroderma pigmentosa |

| Odors: | |

| Cat urine | β-Methyl-crotonyl-CoA carboxylase deficiency |

| Maple | Maple syrup urine disease |

| Musty | Phenylketonuria |

| Rancid butter | Methionine malabsorption syndrome |

| Sweaty feet | Isovaleric acidemia |

| Organomegaly | Aminoacidopathies, CDG, galactosemia, glycogen storage diseases, LSD, Zellweger syndrome |

| Peripheral neuropathy | AT, Bassen-Kornzweig syndrome, cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis, Cockayne syndrome, LSD, Refsum disease |

| Short stature | Cockayne syndrome, Cornelia de Lange syndrome, hypothyroidism, leprechaunism, LSD, Prader-Willi syndrome, Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome, Seckel bird-headed dwarfism |

| Seizures | Aminoacidopathies, CDG, glycogen synthetase deficiency, HIE, LSD, Menkes disease, mitochondrial diseases, neuroaxonal dystrophy |

| Skin abnormalities: | |

| Hyperpigmentation Hypopigmentation |

Adrenoleukodystrophy, AT, Farber disease, neurofibromatosis, Niemann-Pick disease, tuberous sclerosis complex, xeroderma pigmentosa |

| Nodules | Chédiak-Higashi syndrome, incontinentia pigmenti, Menkes disease, tuberous sclerosis complex |

| Thick skin | Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis, Farber disease, neurofibromatosis, LSD, Refsum disease, |

| Thin skin | Sjögren-Larsson syndrome, AT, Cockayne syndrome, progeria, xeroderma pigmentosa |

AT, Ataxia-telangiectasia; CDG, congenital disorders of glycosylation; CHARGE, coloboma, heart disease, choanal atresia, retardation, genital anomalies, ear anomalies; HIE, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy; LSD, lysosomal storage diseases; SCD, spinocerebellar degeneration; SSPE, subacute sclerosing panencephalitis.

From Sherr, E.H., Shevell, M.I., 2006. Mental retardation and global developmental delay, in: Swaiman, K.F., Ashwal, S., Ferriero, D.I. (Eds.), Pediatric Neurology, Principles and Practice, fifth ed. Mosby, Philadelphia.

Diagnostic Testing

Genetic Testing

Frequently, however, the underlying cause is unknown despite the acquisition of a comprehensive history and physical examination. In these situations, a chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) should be offered to the family, since it has the highest diagnostic yield of any single assay for children with global developmental delay: approximately 8% to 12%. A clinical CMA tests for submicroscopic deletions or duplications that can be associated with a variety of neurodevelopmental delays, including global developmental delay. This is also the first-line test for individuals with nonspecific intellectual disability, an autism spectrum disorder, and multiple congenital anomalies (Miller et al., 2010). Though this test has a relatively high diagnostic yield, it will typically not detect inversions and other balanced rearrangements. Consequently, if the microarray is within normal limits, a follow-up high-resolution karyotype should be considered.

In children with global developmental delay, it is important to confirm that the universal newborn screening test was normal at birth. Nonetheless, the diagnostic yield of biochemical testing in a child with nonspecific global developmental delay is quite low (<1%) (Moeschler and Shevell, 2006). The yield may be slightly higher if there is a history of: (1) metabolic decompensation, hyperammonemia, hypoglycemia, protein aversion, acidosis or other evidence of an inborn metabolic disease; (2) neonatal seizures, stroke, movement disorder, or other neurological diagnosis; (3) a family history of unexplained death or neurological disease in a first-degree relative; (4) parental consanguinity; or (5) prenatal history of acute fatty liver of pregnancy (AFLP) or toxemia with hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets (HELLP). Physical examination findings that should increase the suspicion of a metabolic disease include microcephaly, macrocephaly, growth failure, unusual odor, coarse facial features, unusual birthmarks, abnormal hair, hypotonia, dystonia, and focal weakness.

Neuroimaging

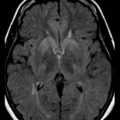

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain has a yield of 65% in children with developmental delay (Shevell et al., 2003). The abnormalities most frequently identified include cerebral malformations, cerebral atrophy, delayed myelination, other white matter changes, postischemic changes, widened Virchow-Robin spaces, and phakomatoses. However, many of these changes are nonspecific and do not lead to the diagnosis of a specific etiology for the developmental delay. The yield of a brain MRI is higher if the child has neurological abnormalities on physical examination such as microcephaly, macrocephaly, focal neurological deficits, epilepsy, strokes, or a movement disorder. Given the nonnegligible risk of sedation in a child with global developmental delay, neuroimaging with an MRI should be recommended as a first-line study in children with focal neurological findings and may be offered as a second-line study if genetic testing is nondiagnostic.

Regression

In a child with neurological regression, a thorough neurological history and examination is warranted. The history should focus on any modifiable factors that could contribute to neurological decline, including worsening of another medical problem, recent modification to an existing medication regimen or initiation of a new medication, recovery from a prolonged acute illness or surgery, or a psychosocial stressor. All children with neurological decline should receive an extensive physical examination, with attention to those aspects of the examination that could provide clues to an underlying neurodegenerative disease (see Table 7.5). A pediatric ophthalmologist should also examine the patient for ocular stigmata of a neurodegenerative disease (see Table 7.4). A brain MRI should be performed to assess for changes that can be seen in many regressive diseases—atrophy, ventriculomegaly, white matter changes, and infarcts. Additional studies should be considered based on the patient’s clinical presentation: comprehensive metabolic panel, lipid panel, creatine kinase, EEG, EMG and nerve conduction studies, echocardiogram, and hearing test.

Council on Children with Disabilities, American Academy of Pediatrics. Identifying infants and young children with developmental disorders in the medical home: an algorithm for developmental surveillance and screening. Pediatrics. 2006;118:405-420.

Miller D.T., Adam M.P., Aradhya S., et al. Consensus statement: chromosomal microarray is a first-tier clinical diagnostic test for individuals with developmental disabilities or congenital anomalies. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86:749-764.

Moeschler J.B., Shevell M., the Committee on Genetics. Clinical genetic evaluation of the child with mental retardation or developmental delays. Pediatrics. 2006;117:2304-2316.

Shevell M., Ashwall S., Donley D., et al. Practice parameter: evaluation of the child with global developmental delay. Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and The Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society. Neurology. 2003;60:367-380.