21

Gestational trophoblastic disease

Trophoblast cells in health and disease

Management of molar pregnancies

Introduction

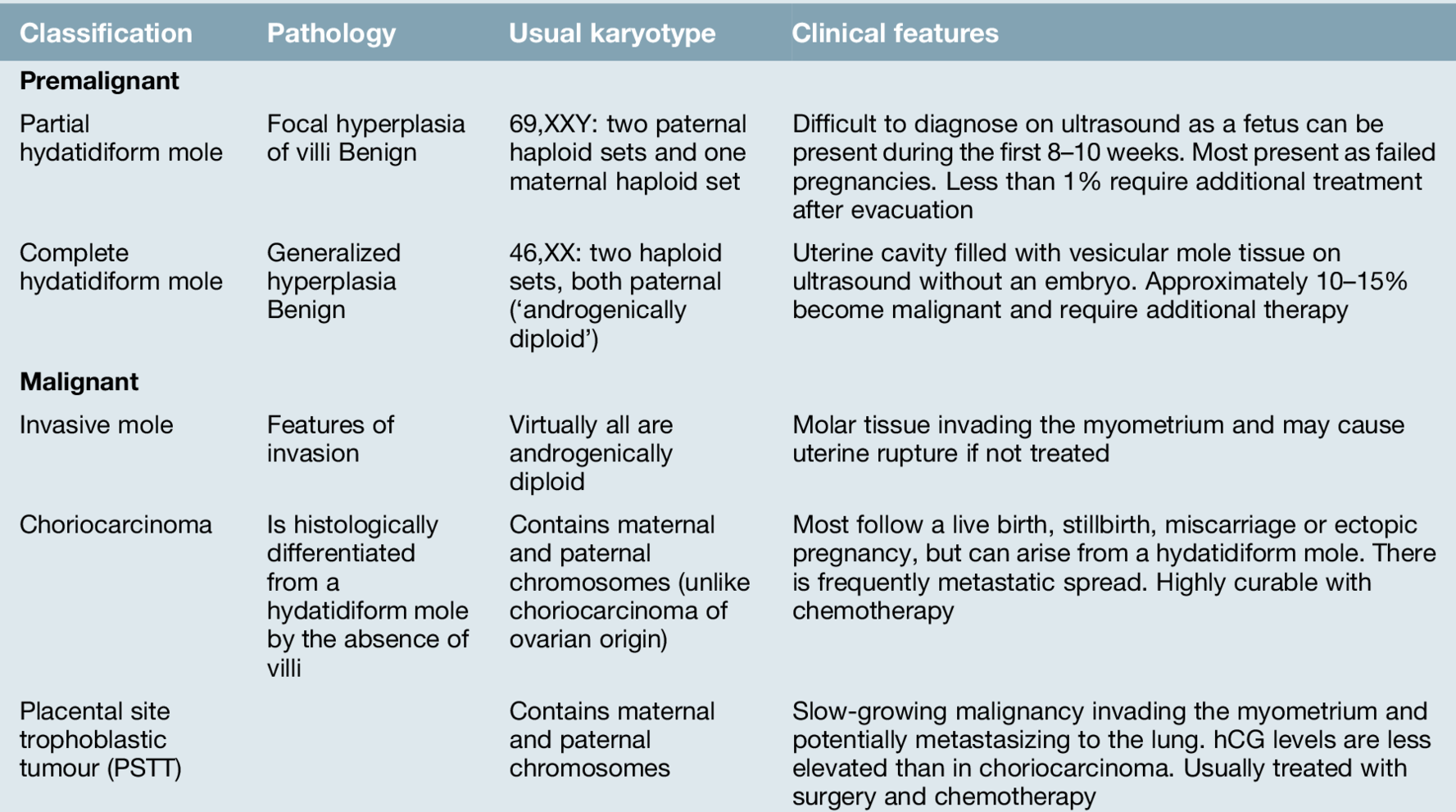

Gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD) forms a group of conditions characterized by abnormal proliferation of trophoblastic tissue with hCG production. There are premalignant and malignant forms: the premalignant form is subdivided into partial and complete hydatidiform moles, and the malignant form into invasive moles, choriocarcinoma, and placental site trophoblastic tumours (Table 21.1). The malignant forms of GTD have a number of important differences from other more common forms of malignancy in terms of aetiology, genetic make-up, pathophysiology and responsiveness to treatment. Fortunately, the malignant forms of trophoblast disease are extremely sensitive to chemotherapy, and treatment routinely results in cure, even in patients presenting with widespread disease.

Even molar pregnancy, which is the most common form of GTD, is a relatively rare condition, with an estimated worldwide incidence of around 1–3 cases for every 1000 live births. The incidence has previously been thought to vary significantly across different geographical regions and racial groups, with estimates from the 1960s showing a near 10-fold higher incidence in Korea, the Philippines and China compared with Europe and the USA. More recent data, however, shows that rates of 1–3 cases per 1000 are reported in nearly every worldwide series.

The incidence of molar pregnancies is higher at the extremes of reproductive age, at approximately 1 in 30 in those aged under 15 and as high as 1 in 5 in those for women in their late 40s or early 50s. As these extremes of the reproductive age group make up only a very small proportion of the women who become pregnant, over 90% of cases occur in women aged 18–40.

In view of the rarity of the condition, ongoing management of trophoblast after the initial uterine evacuation is best provided by a specialist centre.

Trophoblast cells in health and disease

In a healthy pregnancy, the trophoblast cells make up a key component of the placental tissue. Their role is to promote invasion of the conceptus into the lining of the uterus, invade into the uterine blood vessels, promote angiogenesis and produce human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG).

The malignant forms of GTD, both those arising from molar pregnancies and those arising from malignant transformation of cells in healthy placentae, share many of these characteristics. In addition to the abilities to invade into the lining of the uterus and stimulate new blood vessels, the malignant cells are also able to spread to other organs of the body and grow at a very fast rate, without any control on their division. Fortunately, despite these changes, the production of hCG is always retained, and this is extremely helpful in establishing a diagnosis and in monitoring the response to treatment.

Premalignant GTD

Premalignant GTD (Table 21.1) is divided into partial and complete molar pregnancies. The original derivation of the term hydatidiform mole, from the Greek hydatis meaning a watery vesicle and the Latin mola meaning a shapeless mass, is an accurate description of the appearance of a complete molar pregnancy evacuated after the first trimester. With the near-universal use of first trimester ultrasound, however, this florid appearance is now rarely seen in well-resourced countries.

Partial hydatidiform mole

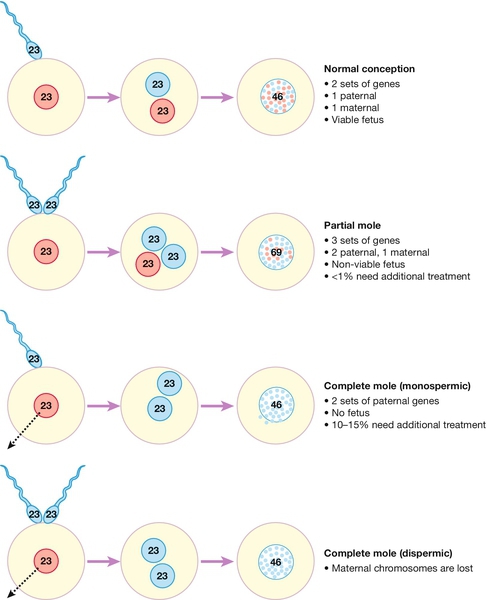

Molar pregnancies occur as the result of an error in either the production of the oocyte or at the time of fertilization. Normally, fertilization combines a 23,X set of haploid chromosomes from the ovum with either a 23,X or 23,Y haploid set from the sperm, the result being a diploid 46,XX or 46,XY zygote which has the correct balance of maternal and paternal genes. In contrast, a partial molar pregnancy has 69 chromosomes, 23 from the mother and the other 46 paternally derived, usually from the entry of two separate sperm into the ovum (Fig. 21.1).

In a partial molar pregnancy, there is usually an embryo which may be seen on an early ultrasound. The ultrasound may have been ‘routine’, or have been carried out because of vaginal bleeding, vaginal discharge, abdominal pain or excessive morning sickness. Although structurally abnormal, there may be no obvious ultrasound features of this in the early first trimester and the diagnosis may therefore not become apparent until histological tissue examination is carried out after a failed pregnancy. The features are of focal hyperplasia and swelling of the villi, though many areas do not have these obvious changes and distinguishing a partial mole from a hydropic miscarriage can be difficult. Fortunately, the risk of malignant change after a partial molar pregnancy is less than 1%, and very few partial mole patients require chemotherapy.

Complete hydatidiform mole

In contrast to partial molar pregnancies, complete molar pregnancies have the correct number of chromosomes, with the majority having a 46,XX karyotype. In complete molar pregnancies, however, all the genetic material is from the father and they are therefore termed androgenetic in origin.

There appears to be two mechanisms by which this genetic combination arises:

![]() the maternal 23,X haploid set of chromosomes in the ovum may be lost at the time of fertilization and the 23,X haploid paternal chromosomes from the fertilizing sperm may duplicate themselves, giving rise to the 46,XX cell

the maternal 23,X haploid set of chromosomes in the ovum may be lost at the time of fertilization and the 23,X haploid paternal chromosomes from the fertilizing sperm may duplicate themselves, giving rise to the 46,XX cell

![]() alternatively, an ‘empty’ ovum may be fertilized by two separate spermatozoa (dispermy), which also leads to a paternally derived karyotype.

alternatively, an ‘empty’ ovum may be fertilized by two separate spermatozoa (dispermy), which also leads to a paternally derived karyotype.

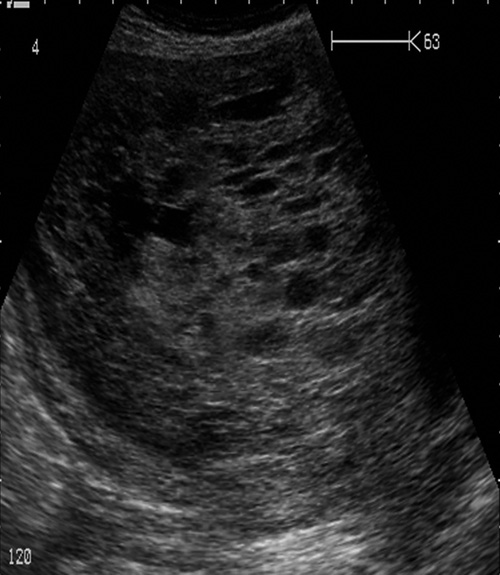

In a complete molar pregnancy, there is no fetal material, and the placental tissue has marked hyperplasia and gross vesicular swelling of the villi. The classical macroscopic ‘bunch of small grapes’ appearance of a complete molar pregnancy generally occurs later in the second trimester; thus, as most are usually molar pregnancies are now diagnosed in the first trimester, this appearance is less often seen in well-resourced countries (Fig. 21.2). In areas without routine ultrasound, the presentation may be later with abnormal clinical findings including: a large-for-dates uterus (from the bulk of the tumour), hyperemesis or, more rarely, thyrotoxicosis resulting from the supraphysiological levels of hCG, which mimic the action of TSH.

Approximately 10–15% of complete molar pregnancies become malignant and will require chemotherapy after their surgical evacuation.

Malignant GTD (Table 21.1)

Invasive mole

Invasive molar pregnancy is rare in areas with routine first trimester ultrasound but occurs when the molar tissue invades predominantly into the myometrium. The clinical presentation is with a uterine mass and an elevated hCG level. As a result of the myometrial invasion, the tumour can lead to uterine rupture and present with abdominal pain and bleeding. Histologically, invasive mole has a similar appearance to a complete molar pregnancy and usually responds well to chemotherapy.

Choriocarcinoma

Choriocarcinoma is a highly malignant tumour arising from malignant transformation of the placental trophoblast cells, and histologically is characterized by haemorrhage, necrosis and intravascular growth. Choriocarcinoma lacks the villous structure of the normal trophoblast or molar pregnancy and is very rare, with approximately 1 case per 50 000 live births. Choriocarcinoma may become apparent shortly after a pregnancy or can present after an interval of up to 20 years after the causative pregnancy.

Presentation is usually with persistent vaginal bleeding and a markedly raised hCG (the serum hCG level, which is usually < 100 000 IU/L at the time of delivery, should fall to normal within 3 weeks postpartum). Diagnosis can also follow presentation of a metastasis in:

![]() the lung, causing haemoptysis or dyspnoea

the lung, causing haemoptysis or dyspnoea

![]() the brain, leading to neurological abnormalities

the brain, leading to neurological abnormalities

![]() the gastrointestinal tract, causing chronic blood loss or melaena

the gastrointestinal tract, causing chronic blood loss or melaena

![]() the liver, leading to jaundice

the liver, leading to jaundice

![]() the kidney, causing haematuria.

the kidney, causing haematuria.

The finding of an elevated hCG level in a woman with advanced cancer is highly suggestive of choriocarcinoma.

In contrast to molar pregnancies, there do not appear to be any risk factors or higher-risk groups for the development of choriocarcinoma.

Placental site trophoblastic tumour (PSTT)

PSTT is the least frequent type of gestational tumour, with approximately 1 case for every 200 000 live births. In contrast to choriocarcinoma, PSTT is believed to arise from the intermediate trophoblastic cells, which have a lower capacity to invade and also make relatively less hCG than the syncytiotrophoblast cells that give rise to choriocarcinoma.

The presentation of PSTT is similar to that of choriocarcinoma, though interestingly, it occurs predominantly after the delivery of a female infant and is more likely to be associated with hCG-induced amenorrhoea. It usually presents rather later than choriocarcinoma, tends to grow more slowly and is less chemosensitive.

Management of molar pregnancies

Following an ultrasound scan suggestive of a molar pregnancy, the first step is to arrange a uterine evacuation. In a complete molar pregnancy, where there are no fetal parts, the evacuation should be performed by a suction procedure. The risks of bleeding and perforation during surgical evacuation are significant, however, and the procedure should be performed by a senior surgeon and with cross-matched blood available. Medical evacuation may be appropriate for a partial mole, particularly if larger fetal parts are present, but this should be followed with a surgical evacuation of any retained products of conception. It is recommended that oxytocin is avoided until after the uterine evacuation is completed to minimize the risk of distant spread by uterine contractions.

Following the evacuation, the diagnosis is confirmed on histological examination and supported, if needed, by cytogenetic studies of the trophoblast cells. The registration and follow-up of molar pregnancy is discussed below.

Follow-up after a molar pregnancy

Following the evacuation of a complete molar pregnancy, there is an approximately 10–15% chance of persistent disease and the development of malignancy, while after a partial molar pregnancy, the risk is only 1%. There is no effective prospective method of determining which patients will develop persistent disease and will therefore require further treatment, but hCG follow-up after the evacuation allows this group to be identified.

To ensure that this is meticulously carried out, in the UK, follow-up of molar pregnancies is organized through three central trophoblast centres (in London, Sheffield and Dundee). Each case of molar pregnancy is registered with the nearest laboratory, which will then organize the hCG follow-up directly. This system has been a major factor in producing the extremely high cure rates now seen for the disease, and the clinical experience in these centres has led to most of the major therapeutic developments in these rare tumours.

In the majority of patients with molar pregnancies, the hCG values fall to normal within 2 months and relapse after this point is very rare. The current advice is that follow-up is needed for only 6 months from the time of the evacuation or for 6 months from the first normal hCG level in those where the rate of fall is slower. It is also recommended that women postpone a further pregnancy during the follow-up period, as the hCG from the new pregnancy could mask the hCG from relapsed disease, and this would delay diagnosis and treatment.

There is an increased risk of a further molar pregnancy in subsequent pregnancies, with the risk estimated at approximately 1:70. For women unfortunate enough to have two molar pregnancies, the risk of a third in a later pregnancy is in the order of 1:10.

Management of malignant GTD

Following evacuation of a molar pregnancy, there are a number of indications for further treatment (Box 21.1). The most frequent of these is a rise or a plateau in the hCG levels after the evacuationThe majority of patients receive treatment with simple single agent chemotherapy, which has a high cure rate and is generally well tolerated (Fig. 21.3). A few women who have completed their families and have no evidence of spread may opt instead for a hysterectomy, but they still require careful follow-up as occult extrauterine disease may exist and chemotherapy could still be required.

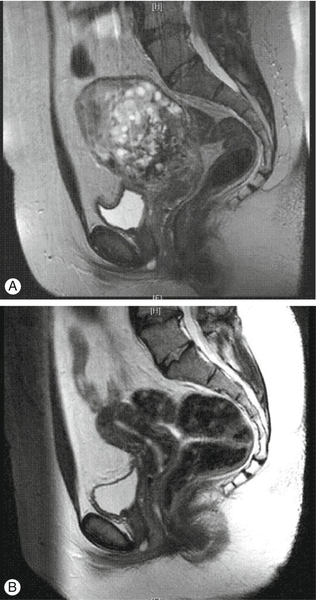

Fig. 21.3Invasive complete molar pregnancy.

(A) MRI appearance prior to chemotherapy treatment. (B) Follow-up scan performed 3 months after chemotherapy completion.

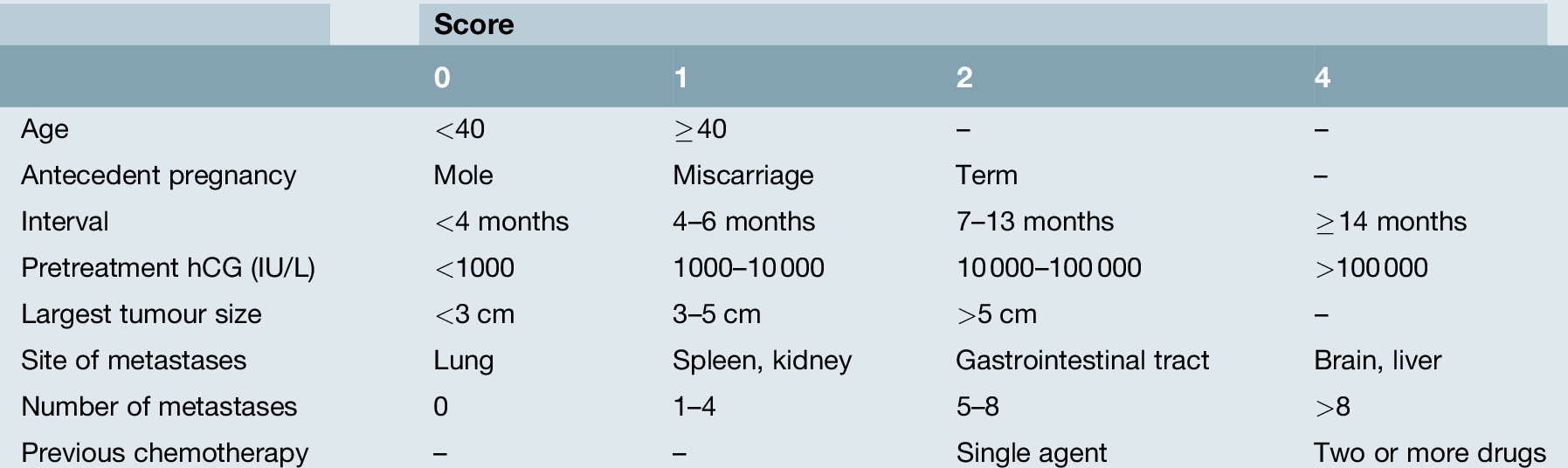

In contrast, all patients with choriocarcinoma occurring after a pregnancy require chemotherapy and surgery in this group is rarely useful. As the disease is so exquisitely sensitive to chemotherapy, the majority of patients with GTD occurring after a molar pregnancy can be treated with low toxicity single-agent chemotherapy using methotrexate. This is well tolerated, has minimal side-effects, does not cause hair loss or significant sickness, and there is minimal risk of neutropenia. In contrast, some GTD patients, particularly those with choriocarcinoma after a normal pregnancy, require treatment with a more toxic combination chemotherapy regimen, usually EMA-CO.

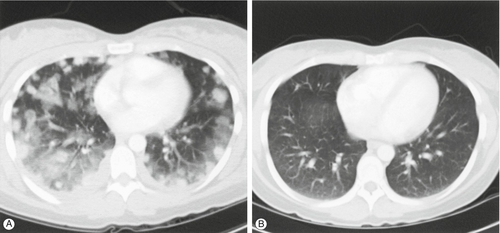

To help determine which type of treatment is required, the FIGO scoring system can be used (Table 21.2). This allows the calculation of a score based on eight variables. Patients scoring ≤ 6 points receive methotrexate chemotherapy, while those scoring ≥ 7 start with the EMA-CO combination chemotherapy. In the UK, overall cure rates of 100% for those in the low-risk treatment group and approximately 90% for those in the high-risk group, including those patients presenting with advanced disease (Fig. 21.4), can be expected. The small number of patients who are difficult to cure usually present unwell with choriocarcinoma and a long interval from their causative pregnancy and may die before treatment can be commenced, or from drug resistant disease.

(A) CT scan of the chest, demonstrating extensive pulmonary metastases and haemorrhage, in a patient with choriocarcinoma, presenting 1 month after a normal delivery. (B) A CT scan performed 6 months later shows the complete resolution of the disease in response to chemotherapy.

After the completion of chemotherapy, most patients recover fairly rapidly and in nearly all cases, fertility is retained. An interval of 12 months from the completion of chemotherapy to the next pregnancy is usually recommended, and the majority of women are able to have further children. There is thought to be little or no excess risk of fetal abnormalities in this post-chemotherapy group.