chapter 57 Geriatric medicine

AGEING

Essentially, most ageing is healthy and most of us age in a mostly healthy way. (Healthy ageing is covered in Ch 58.) However, with time the number of organ systems within an individual that begin to age in an unhealthy way increases, so that by age 90 years it is uncommon to exhibit only healthy ageing. Frailty can be seen as a transition stage between healthy and unhealthy ageing. Factors that increase the chance of healthy ageing include genes, physical activity, cognitive stimulation, social engagement, diet and aggressive detection and management of disease risk factors.

EVALUATION OF THE OLDER PERSON

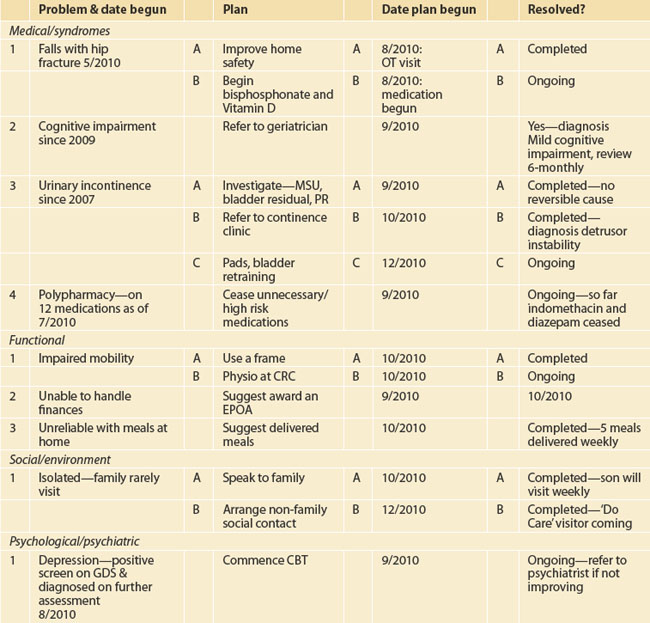

Particular attention needs to be paid to the features of geriatric medical syndromes, including dementia, impaired mobility and falls, incontinence and medication-related issues. There have been several checklists/proformas developed by GP divisions and individual practices to assist this assessment process. These are particularly useful when carrying out routine comprehensive assessments. A suggested checklist is shown in the appendix. Ideally, this information will then be transformed into a problem list with a management plan—an example is shown in Table 57.1. It will be seen that this is best developed as a dynamic process with additional management of the identified problems added as they occur—so a word processed document on computer would be more appropriate than a single hard copy.

PHARMACOLOGICAL ISSUES, INCLUDING POLYPHARMACY

BACKGROUND AND PREVALENCE

Medication issues in older people include polypharmacy (taking a large number of medications), reduced compliance (‘concordance’), drug–drug interactions and adverse drug reactions. Older people consume a disproportionately large number of prescribed drugs, partly because they are more likely to be ill and partly because it can be more difficult to reach a precise diagnosis. On average, an older person in the community takes three prescribed drugs, and this rises to 7–10 in care settings. CAMs and other over-the-counter (OTC) medications are also used extensively by older people. Unfortunately, it is rare for a GP to have a completely accurate list of all the medications their patient consumes—this is partly because the patients themselves cannot always accurately recall them (and may not feel it necessary to mention OTC/CAM medications) and partly because of poor communication from acute-care facilities and specialists. The best way to obtain an accurate list is to visit the patient’s home and ask to see everything they use, or to ask them to put all the medications in a bag and bring them to your office.

Reduced compliance is common at all ages, but is particularly an issue in older people, who take more medications, may not hear or recall or be able to read instructions, may have difficulty opening packages and can be on complicated drug regimens. Fortunately, under-compliance may somewhat protect them from adverse drug reactions, but it does contribute to poorer disease control.

MANAGEMENT

Along with regular medication reviews, there should be a sustained intention to minimise the number of medications an older person takes, but also to ensure that all conditions are being treated effectively. ‘De-prescribing’ is both possible and beneficial, and the basic steps are shown in Box 57.1.1 Unnecessary medications may include analgesics and laxatives no longer needed, or an antipsychotic for behavioural symptoms that are no longer complicating dementia. Additionally, many prophylactic medications (e.g. statins, bisphosphonates) may no longer be necessary as death approaches (palliative care, end-stage dementia). High-risk medications include anticholinergics (benztropine and benzhexol) and long-acting benzodiazepines.

IMPORTANT PITFALLS

Also, when a medication is ceased the patient may reintroduce it if not supported and reviewed (e.g. temazepam—cessation in hospital is almost always followed by recommencement after discharge).

CONFUSIONAL STATES: DELIRIUM AND DEMENTIA

DELIRIUM

Aetiology

Delirium always has a medical cause.2 The most common causes include infections, metabolic disturbances (e.g. electrolyte deficiencies, hyperglycaemia, hypercalcaemia) and drugs (adverse effects or drug withdrawal). Other causes include pain, intracerebral lesions, myocardial infarction, organ ischaemia, faecal impaction and epilepsy.

Management

Prevention of delirium can be achieved—in a seminal study, Inouye and colleagues3 reduced the incidence by 40% through the multifactorial approach outlined in Box 57.2.

Pitfalls

Under-investigating delirium can worsen the outcome—delirium is a sign that something serious is underlying.

DEMENTIA

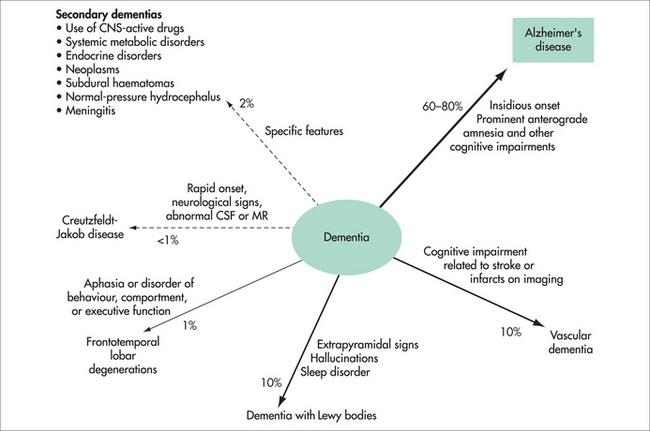

Aetiology

It is not known why one individual develops dementia and another does not. There are genetic mutations that nearly always cause dementia, but this early-onset dementia (in the forties or fifties) is very rare. Risk factors for the much more common late-onset dementia include older age, family history of dementia, apolipoprotein E4 (a carrier of cholesterol), previous head injury, less formal education, lower socioeconomic status and cardiovascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, smoking, atrial fibrillation, past cardiac surgery). There are also protective factors, including active leisure activities, physical activity, social contact and marriage, moderate alcohol use, exposure to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents, omega-3 fatty acids and use of vitamins E and C. It is also becoming apparent that attentional training, such as mindfulness-based practices, is associated with cell maintenance and neurogenesis in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus.4

There are over 200 other causes of dementia but these are uncommon. A few are occasionally at least partially reversible (e.g. hypothyroidism, vitamin B12 deficiency, syphilis) and explain why investigations for these are performed. Normal pressure hydrocephalus (characterised by dementia, urinary incontinence and gait disturbance) is also potentially reversible, although many neurosurgeons are reluctant to perform the required shunt, as results are often disappointing.

Investigations

Routine blood tests and neuroimaging should be performed as shown in Box 57.3—mainly to rule out potentially reversible causes of dementia and comorbidities. Increasingly, specialists are ordering tests to ‘rule in’ a diagnosis of dementia and to characterise the type.

The MRI of the brain is moving towards this identification of dementia—for instance, hippocampal atrophy is seen in AD, and frontal atrophy in FTD. The PET scan is only available in a few centres but can be most useful. The FDG PET shows a characteristic pattern in AD (bilateral temporoparietal hypometabolism with sparing of occipital metabolism), whereas sparing of the posterior cingulate metabolism is very much against a diagnosis of AD. In DLB, occipital metabolism is reduced and in FTD frontal and temporal metabolism is down, with characteristic patterns in the language variants. Another PET technique available in even fewer centres is amyloid imaging using PIB or other agents. Absence of amyloid excludes AD, and its presence excludes FTD. Amyloid is frequently found in DLB and vascular dementia. Combining both PET techniques achieves very high diagnostic accuracy.

Management

Pharmacological

The great advance in dementia therapy has been the development of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEIs).5 In AD, and also in DLB and vascular dementia, there is a deficiency of acetylcholine (ACh). This is due to damage either to the central nucleus (nucleus basilis of Meynert) that produces the enzyme that makes ACh (in AD and DLB) or to the axons within which this enzyme is transported (vascular dementia). The AChEIs boost ACh levels by inhibiting another enzyme, at the synapse, which degrades ACh. These agents include donepezil (Aricept®), galantamine (Reminyl® or Razadyne®) and rivastigmine (Exelon®). They differ somewhat in action, with galantamine also stimulating nicotinic receptors and rivastigmine also inhibiting another enzyme that breaks down ACh (butyrylcholinesterase), but no study has convincingly demonstrated that one agent is superior to others. At this time, only rivastigmine is given more than once daily, but a once-daily patch preparation is marketed in many countries. These agents have predictable cholinergic side effects, including nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, anorexia and weight loss. Such symptoms can be significant in about 20% of patients but usually attenuate over 1–2 weeks. More serious and rarer adverse effects include bradycardia, peptic ulceration and precipitation of asthma, so they should not be used in patients with such conditions until the illness is well controlled (e.g. Helicobacter eradication or insertion of a pacemaker).

The other pharmacological area of management is the use of atypical antipsychotic agents for the behavioural disturbances (‘challenging neuropsychiatric symptoms’) that can complicate dementia.6 Several trials have demonstrated modest efficacy of low doses of risperidone for agitation, aggressive and psychosis complicating more severe dementia, and there is also some (but less) data to support olanzapine and haloperidol. As these agents are usually used for weeks and months rather than days, side-effect profiles must be considered, and the extrapyramidal effects of haloperidol make it usually an inappropriate choice. While quetiapine has some support due to it almost completely lacking extrapyramidal adverse effects, there are almost no data to support its efficacy for this syndrome.

Other agents for behavioural disturbance have much less supportive efficacy data and include benzodiazepines (some role for anxiety), antidepressants (appropriate for depression, which not infrequently complicates dementia) and mood stabilisers (e.g. valproate). A psychogeriatrician or geriatrician can be a useful resource if behavioural disturbances are proving difficult to manage.

Complementary therapies

High doses (above 400 IU/day) of vitamin E have been shown in a meta-analysis10 to be associated with increased mortality and other adverse events, so daily doses should not exceed this.

Important pitfalls

INSOMNIA

AETIOLOGY

There are changes in circadian rhythm with ageing that tend to move older people to earlier retirement to bed, then many hours spent awake in the morning before rising. Thus, sleep time may be normal but the longer time in bed can be perceived as insomnia. Most insomnia in older people is accompanied by pain and/or physical illness and other comorbidities, although it is arguable as to whether these are the cause of the insomnia. Common conditions associated with insomnia are shown in Box 57.4. The main aetiological factor behind insomnia, however, is probably the sleep changes that occur with ageing. It should also be remembered that sleep quality and mental health are intimately related. Although depression is a common cause of insomnia, insomnia is a common cause of depression. Therefore, the assessment of sleep problems should never ignore mental health issues, and the management of mental health issues should always involve behavioural approaches to improve sleep.

MANAGEMENT11

Prevention, self-help and lifestyle

Insomnia can be both prevented and managed by a range of sleep hygiene techniques as outlined in Box 57.5. The individual should be persuaded to go to bed at a comfortable time (e.g. 11 pm) and rise at a regular time that allows sufficient but not excessive sleep (e.g. 7 am). Long hours spent reading or watching TV in bed should be discouraged. If there is regular daytime napping, this could be reduced by engaging in other activities—e.g. a walk after lunch rather than a nap. Preparation for bed can include a hot (non-caffeinated) beverage and listening to relaxing music (before, not in, bed). At least 30 minutes daily of moderate activity (e.g. a walk), preferably in sunlight, should be encouraged. Often people are relieved to know that if they feel refreshed by 6½ hours sleep nightly, that is all they need—not 8–10 hours, as some of their friends may be requiring. Patients need to be reassured that sleep requirement may change with age.

DIABETES AND THYROID DISORDERS

DIABETES

Pharmacological management is indicated when diet and other lifestyle changes fail to control sugar levels, and initial therapy is usually with a sulforylurea and/or metformin.12 Only shorter-acting sulforylureas should be used (e.g. gliclazide)—even glibenclamide (gliburide) has too long a half-life, and therefore too high a risk of inducing hypoglycaemia, in older people. If maximal doses of these fail to achieve control, consideration should be given to adding a ‘glitazone’ such as rosiglitazone, but recent concerns about increased mortality and cardiac adverse events from these agents should be considered. These agents should be avoided if there is heart failure, and the patient should be monitored for fluid accumulation. If oral therapy is failing, insulin should be added. Initially, once-daily longer-acting insulin should be trialled. There is synergism with metformin, which can therefore be continued, but not with the sulfonylureas, which should be ceased. If hypoglycaemia occurs despite insulin dosage adjustments, one of the newer semi-synthetic insulins (e.g. insulin glargine) should be substituted, as these have less risk of causing severe hypoglycaemia.

Other complementary therapies are discussed in the diabetes chapter (Ch 26).

WOUNDS

IMPORTANT CONDITIONS

Pressure ulcer incidence is reported to be up to 38% in acute care.14 In 2006 the Pressure Ulcer Point Prevalence Study (PUPPS) found a prevalence of 26% in public hospitals.

Approximately 15% of individuals with diabetes will develop an ulcer at some point.

PATHOLOGY

DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH

History

History should aim to identify the aetiology of the wound and current barriers to healing. Factors suggestive of chronic venous insufficiency include varicose veins, previous deep vein thrombosis, surgery or trauma to the limb, obesity, long periods of standing (enquire about employment history) and increased intraabdominal pressure. These wounds frequently commence spontaneously. Risk factors for peripheral vascular disease are as for cardiovascular disease: hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, smoking, family history and diabetes. Enquire about previous amputations. Patients with foot lesions should be questioned regarding causes of neuropathy. Patients with diabetic foot wounds generally have peripheral neuropathy, a history of initiating trauma and often poor arterial supply or infection.

Examination

The wound itself should be described, including: location, dimensions (including depth), edge, the presence of slough or necrotic tissue, signs of infection or inflammation and the volume and type of exudates.15

Skin tears may be graded according to the amount of skin lost; the STAR tool by the Silverchain group is useful.16

INTEGRATIVE MANAGEMENT

Prevention

Peripheral vascular disease may be minimised through control of cardiovascular risk factors.

Pressure area prevention is the cornerstone of management. Braden, Norton and Waterlow scales will stratify the risk of pressure areas. Air mattresses and cushions, gel cushions, bed cradles and orthotic devices have become part of pressure care of the immobile patient. Nursing care such as turning patients and adequate nutrition is still vital.14

Self-help/lifestyle

Lifestyle factors such as smoking cessation and ensuring adequate diet and hydration17 help wound healing. Exercise is beneficial for venous leg wounds in particular.

Complementary therapies

Wound dressings are a fast-growing industry.15 Complementary therapies are also becoming more ‘mainstream’. For example, manuka honey is being developed in new and more user-friendly preparations. Although research is somewhat lacking regarding the true mechanism of action, it is thought to have antimicrobial activity due to the slow release of hydrogen peroxide.15

Dietary supplements are also now considered virtually mainstream in the management of pressure areas. Commercial products containing arginine (an amino acid), vitamin C and zinc have been proved to aid the healing of pressure areas.18 Caution is required with the supplementation of zinc, as its benefit is probably only in those with deficiency and the appropriate dosage is not established. High-dose zinc may be associated with nausea and may result in copper deficiency (which can cause anaemia).19 However, topical zinc oxide preparations may be helpful.20

Horse chestnut is thought to be useful in chronic venous insufficiency. Liver function tests and coagulation profile should be monitored.21

IMPORTANT PITFALLS

Failure to identify the aetiology of the wound, or barrier to healing, is the most important pitfall. For example, if osteomyelitis is present, the overlying ulcer will not heal. Mixed venous and arterial disease is common in the elderly and limits the use of compression. The arterial component is often under-recognised. The principles of moist wound healing do not apply to the dry eschar of digits or heels in ischaemic limbs. These wounds are best kept dry, to limit the risk of infection. Cheaper wound dressings may need to be applied more frequently and slow wound healing, thus increasing the overall cost.

CONTINENCE

IMPORTANT CONDITIONS

PATHOLOGY

Sensory urgency is due to a small-capacity bladder or recurrent urinary tract infections.

Stress incontinence is due to weakened pelvic floor musculature or intrinsic sphincter failure.

It is generally thought that there is no reduction in bowel movement frequency with normal ageing. The elderly community probably overestimates constipation. However, severe constipation is the most common cause of faecal incontinence, with watery stool flowing around the hard faeces. Constipation has many potential causes; those common in the elderly include inadequate fluid or dietary fibre, immobility, medication, bowel pathology, neurological conditions such as stroke and Parkinson’s disease causing slow-transit bowel and poor toileting habits. Inadequate sphincter function due to poor pelvic floor or neurological condition may also result in faecal incontinence.

DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH

History

Consider reversible causes: delirium, urinary tract infection, atrophic vaginitis in women, psychological (severe depression, neurosis), pharmacological, excess fluid intake or output, restricted mobility or environment, stool impaction.22

Regarding constipation and faecal incontinence, the history should include the relevant past surgical history. Diet, fluid intake, mobility, duration of constipation, frequency of bowel actions, character of the stool, pain, straining and laxative use are also vital.23

Consider impact on quality of life—for example, limitation of social activities, sleep disturbance.

INTEGRATIVE MANAGEMENT

Pharmacology

Cholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine) are reported to increase urinary frequency and perhaps urinary incontinence. There is now evidence that anticholinergic treatment for urinary incontinence in this situation may be helpful—although it does seem illogical.22

Benign prostatic hypertrophy may be managed with alpha-1 blockers; androgen blockade is used in cases with clinically enlarged prostate.22

Paramedical

IMPORTANT PITFALLS

PATIENT EDUCATION

CARDIOVASCULAR

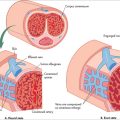

PATHOLOGY

INVESTIGATIONS

INTEGRATIVE MANAGEMENT

Pharmacology

There is currently no effective pharmacological management for chronic valvular disease.

The best management of AF includes management of the cause. A rate control strategy (beta-blocker or non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker ± digoxin) is generally sufficient as it is safer than rhythm control and has similar outcomes. Patients over the age of 75 years with an additional risk factor, such as left ventricular systolic dysfunction, hypertension, diabetes mellitus or previous stroke, benefit from the addition of warfarin therapy. The CHADS2 score helps to assess risk.24 The benefits of anticoagulation must be considered in the context of the patient’s comorbidities. Some studies have suggested that the rate of severe bleeding complication is not as significant as perhaps perceived.25

PAIN IN THE ELDERLY POPULATION

Pain is an ‘unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage. The inability to communicate verbally does not negate the possibility that a patient is experiencing pain and is in need of appropriate pain relieving treatment’ (International Association for the Study of Pain). Up to 50% of older community dwellers and 80% of those in residential care suffer from persistent pain.26

PATHOLOGY

Cell-mediated immunity is impaired with ageing, placing the elderly at risk of reactivation of Herpes zoster and development of PHN.27

DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH

History

Identify the onset, cause and time frame, factors that increase and decrease the pain, severity and impact on lifestyle.28 Gain an understanding of which treatment modalities have already been tried, and their effectiveness. Watch for ‘red flags’ indicating serious underlying pathology, such as thoracic pain, pain associated with incontinence or gait disturbance or back pain in someone with known malignancy.

INTEGRATIVE MANAGEMENT

Prevention

Appropriate treatment of acute pain syndromes and acute illness may help reduce the risk of a pain syndrome becoming chronic. Prevention of Varicella zoster virus infection and immunisation against Herpes zoster may decrease the incidence of this condition in the future.27

General measures

General supportive measures, such as meditation, may be an option in the chronic pain setting, if this suits the patient (see Ch 38, Pain management).

Lifestyle

In many cases, pain cannot be completely eliminated, although self-help and lifestyle strategies can help a person to cope better with it.28 Lifestyle may have to be adjusted to allow best function for the majority of the time.

Pharmacology

For mild to moderate pain, simple analgesics such as paracetamol are preferred.28 Glucosamine and paracetamol may provide enough relief for many patients suffering from osteoarthritis pain. Long-term use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents is best avoided in the elderly due to the side-effect profile (gastrointestinal upset, renal failure, fluid retention, hypertension). COX-2 inhibitors have similar issues.

Newer transdermal patches of fentanyl or buprenorphine have the advantages of steady-state medication delivery and less frequent dosing28; however, side effects including delirium may limit their use. Initiation at low dose, and slow titration, are appropriate in the elderly.

Opioids such as oxycodone and morphine may be required in the elderly patient with severe pain. Constipation, nausea and confusion are common unwanted effects. A long-acting oxycodone for background relief and a short-acting oxycodone for breakthrough pain are usually prescribed. A low dose should be used initially in the elderly, due to pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes related to ageing, caused by altered organ function and volumes of distribution. Initially the dose should be reviewed frequently.29 Aperients are generally prescribed at the same time as opioids, to avoid constipation.

In neuropathic pain syndromes, such as PHN, the combination of opioid and gabapentin or pregabalin is often helpful; tricyclic antidepressants (TCA) and tramadol have also been shown to be of use.30 However, these agents may cause confusion in the elderly and the TCAs have undesirable potential cardiac side effects. Topical capsaicin and lignocaine also show promise.27,30

FALLS

In the elderly the consequences of falls are significant—they include fractures, bruising and developing a fear of falling. Approximately one-third of people aged over 65 years and living in the community will experience one or more falls per year; the number is higher in institutions. Less than 10% of falls result in fracture, but 20% require medical attention.31

Hip fracture is the most serious fall-related injury in older people. Fifteen per cent die in hospital and a third do not survive beyond one year.32 However, other fractures, intracranial hemorrhage and the development of fear of falling are also important.

DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH

History

Discuss the history of the falls in detail—for example, where and when they occurred, during what activity and any perceived warning signs. Quantify the number of falls in recent months. Identify the significance of trauma caused by the fall. Ideally, confirm the history of falls with an eye witness.

INVESTIGATIONS

Consulting room

INTEGRATIVE MANAGEMENT

Lifestyle

Evidence suggests that some psychosocial factors have an independent protective effect on hip fracture risk. These include: currently married, living in present residence for 5 years or more, proactive coping strategies, having a higher level of life satisfaction and engagement in social activities in older age.33

Pharmacology

PROGNOSIS

Prevention of falls can be difficult in the elderly. Success is determined by the ability to reverse extrinsic and intrinsic factors. In many cases the falls can only be minimised. Potential trauma may be reduced by osteoporosis and vitamin D deficiency treatment, and items such as hip protectors.32 Falls are one of the most common reasons for institutionalisation of the elderly.

PATIENT EDUCATION

Patients should be educated on:

1 Woodward M. De-prescribing: achieving better health outcomes for older people through reducing medications. J Pharm Pract Res. 2003;33:323-328.

2 Moran JA, Dorevitch MI. Delirium in the hospitalised elderly. J Pharm Pract Res. 2001;31:35-40.

3 Inouye SK, Bogardus ST, Charpentier PA, et al. A multicompartment intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized patients. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:669-676.

4 Holzel BK, Ott U, Gard T, et al. Investigation of mindfulness meditation practitioners with voxel-based morphometry. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2008;3(1):55-61.

5 Hecker JR, Snellgrove AA. Pharmacological management of Alzheimer’s disease. J Pharm Pract Res. 2003;33:24-29.

6 Woodward M. Pharmacological treatment of challenging neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. J Pharm Pract Res. 2005;35:228-234.

7 Sano M, Ernesto C, Thomas RG, et al. A controlled trial of selegiline, alpha-tocopherol, or both as treatment for Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1216-1222.

8 Petersen RC, Thoma RG, Grundman M, et al. Vitamin E and donepezil for treatment of mild cognitive impairment. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2379-2388.

9 MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of antioxidant vitamin supplementation in 20 536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9326):23-33.

10 Miller ERIII, Pastor-Barriuso R, Dalal D, et al. Meta-analysis: high-dosage vitamin E supplementation may increase all-cause mortality. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(1):37-46.

11 Woodward MC. The management of insomnia in older people. Aust J Hosp Pharm. 1996;26:462-465.

12 Crandall J, Barzilai N. Treatment of diabetes mellitus in older people: oral therapy options. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:272-274.

13 De Luise MA. Thyroid diseases in the elderly. J Pharm Pract Res. 2003;33:228-230.

14 Reddy MM, Gill SS, Rochon PA. Preventing pressure ulcers: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296:974-984.

15 Weller C, Sussman G. Wound dressings update. J Pharm Pract Res. 2006;36:318-324.

16 Carville K, Lewin G, Newall N, et al. STAR: a consensus for skin tear classification. Primary Intention. 2007;15(1):18-28.

17 Posthauer ME. Hydration: does it play a role in wound healing? Adv Skin Wound Care. 2006;19:74-76.

18 Desneves KJ, Todorovic BE, Cassar A, et al. Treatment with supplementary arginine, vitamin C and zinc in patients with pressure ulcers: a randomised controlled trial. Clin Nutr. 2005;24(6):979-987.

19 McClain CJ, McClain M, Barve S, et al. Trace metals and the elderly. Clin Geriatr Med. 2002;18:801-818.

20 Agren MS. Studies on zinc in wound healing. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh). 1990;154:1-36.

21 Moses G. Complementary and alternative medicine use in the elderly. J Pharm Prac Res. 2005;35:63-68.

22 Bird MR. Urinary incontinence in the elderly. J Pharm Prac Res. 2004;34:319-321.

23 Woodward MC. Constipation in older people: pharmacological management issues. J Pharm Prac Res. 2002;32:37-43.

24 Gage BF, Waterman AD, Shannon W, et al. Validation of clinical classification schemes for predicting stroke. Results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA. 2001;285:2864-2870.

25 Johnson CE, Lim WK, Workman BS. People aged over 75 in atrial fibrillation on warfarin: the rate of major haemorrhage and stroke in more than 500 patient-years of follow-up. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:655-659.

26 Gibson SJ, Weiner DK. Older people’s pain. Pain: Clinical Updates. 2006;14:1-4.

27 Christo PJ, Hobelmann G, Maine DN. Post-herpetic neuralgia in older adults: evidence-based approaches to clinical management. Drugs Aging. 2007;24:1-19.

28 Katz B. Pharmacological management of pain in older people. J Pharm Pract Res. 2007;37:63-68.

29 Wilder-Smith OHG. Opioid use in the elderly. Europ J Pain. 2005;9:137-140.

30 Hempenstall K, Nurmikko TJ, Johnson RW, et al. Analgesic therapy in postherpetic neuralgia: a quantitative systematic review. PLoS Medicine. 2005;2:628-644.

31 Gillespie LD, Gillespie WJ, Robertson MC, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in elderly people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;4:CD000340.

32 McClure R, Turner C, Peel N, et al. Population-based interventions for the prevention of fall-related injuries in older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;1:CD004441.

33 Peel NM, McClure RJ, Hendrikz JK. Psychosocial factors associated with fall-related hip fractures. Age Ageing. 2007;36:145-151.

34 Minns RJ, Marsh A-M, Chuck A, et al. Are hip protectors correctly positioned in use? Age Ageing. 2007;36:140-144.

35 Howe TE, Rochester L, Jackson A, et al. Exercise for improving balance in older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;4:CD004963.