Genodermatoses

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum

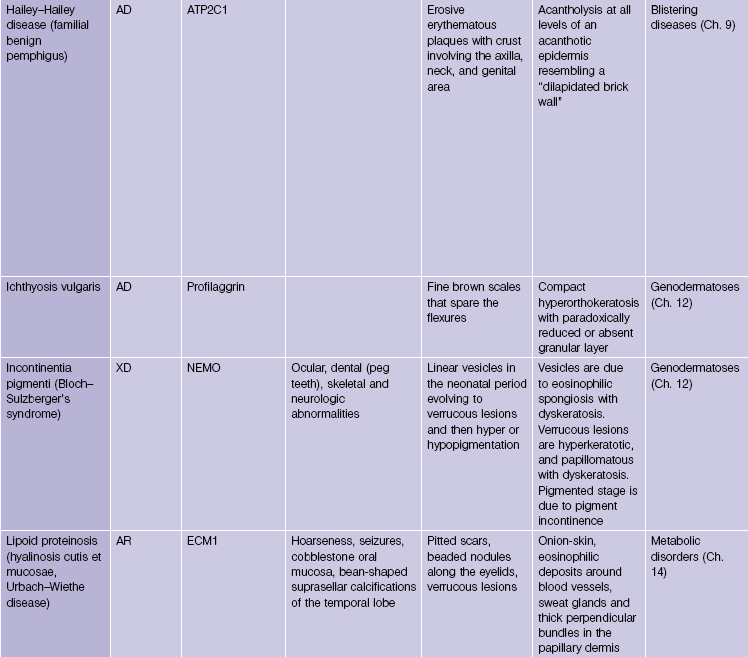

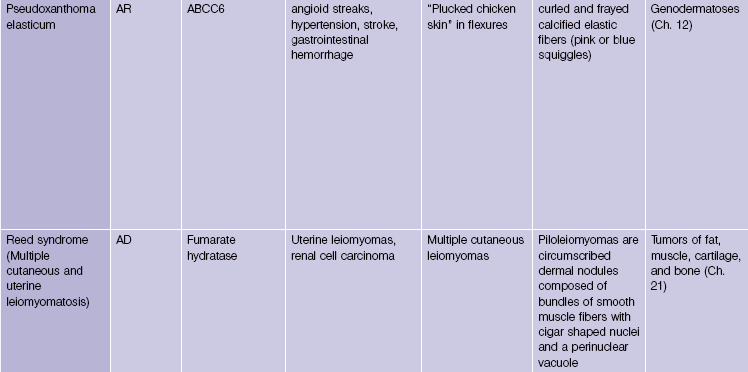

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum is an autosomal-recessive and, less commonly, autosomal-dominant disorder due to a mutation in the ABCC6 transporter gene. It results in calcification of the elastic fibers of the skin, eyes, and artery walls. The skin changes become apparent around the second decade and simulate “plucked chicken skin” in the flexural areas. Biopsy of a scar may reveal the elastic tissue abnormalities in a patient with no cutaneous lesions. Eye changes include angioid streaks and retinal hemorrhage that may cause blindness. The vascular changes may lead to hypertension, stroke, myocardial infarction, mitral valve prolapse, and gastrointestinal hemorrhage.

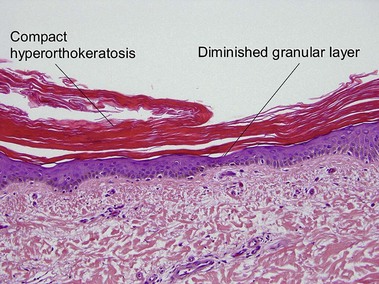

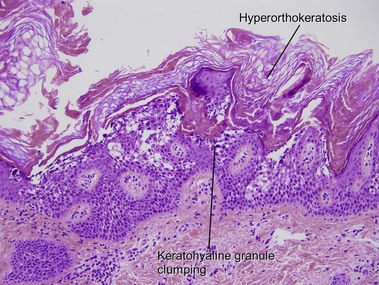

Ichthyosis vulgaris

In most other conditions, hyperorthokeratosis is associated with a prominent granular layer and parakeratosis is associated with a diminished or absent granular layer. Ichthyosis vulgaris (in which there is little to no granular layer despite hyperkeratosis) and axillary granular parakeratosis (in which there is a granular layer despite the presence of parakeratosis) are exceptions to this rule.

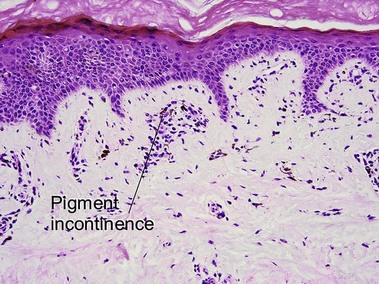

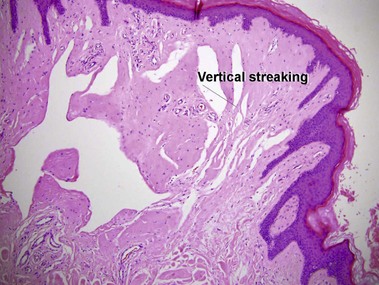

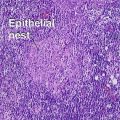

Incontinentia pigmenti (Bloch–Sulzberger syndrome)

This X-linked dominant disorder is typically lethal in males. A mutation in the NEMO gene leads to defective nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) activation. There is evolution through overlapping stages. At birth or soon after, there are linear vesicular lesions that evolve into verrucous lesions weeks to months later. At 3–6 months of age there are streaks and whorls of hyperpigmentation that do not correlate with the areas of prior vesicles. The pattern has been likened to marble cake. Hypopigmentation may replace the hyperpigmentation decades later. Other cutaneous findings include alopecia and nail dystrophy. Ocular, dental (peg teeth), skeletal, and neurologic abnormalities may be present.

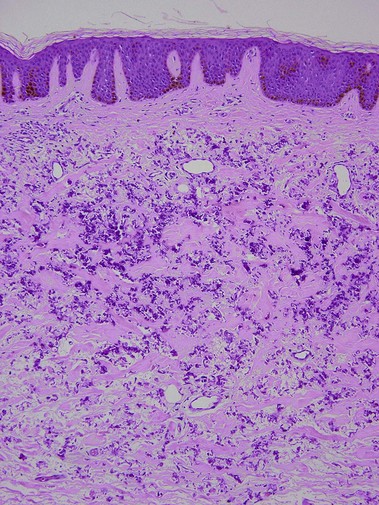

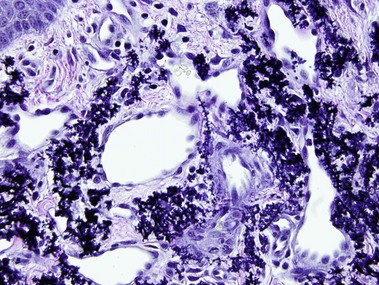

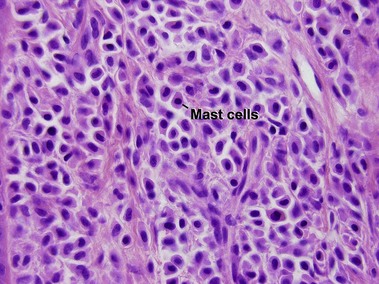

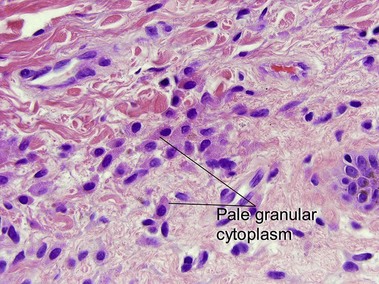

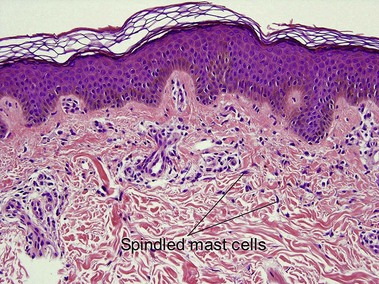

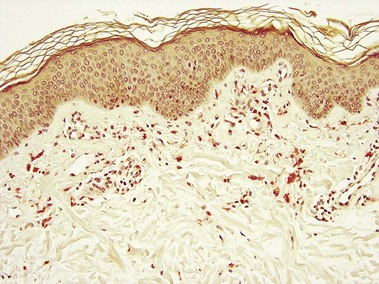

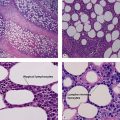

Mastocytosis

Mastocytosis comprises a spectrum of diseases. A solitary mastocytoma may occur in childhood with a tendency to spontaneous involution. Urticaria pigmentosa is a sporadic rather than inherited disorder, characterized by multiple tan macules, papules, or nodules. There is a congenital or early-onset form that is rarely associated with systemic disease and typically clears by puberty. In contrast, adult-onset urticaria pigmentosa persists and can be associated with systemic involvement, especially bone marrow. The majority of lesions urticate with stroking (Darier’s sign). Mutations in c-kit have been found in sporadic adult cases and in children with extensive or persistent disease but not in typical pediatric urticaria pigmentosa. TMEP is a rare adult form of mastocytosis with erythema, telangiectasia, and faint tan macules on the trunk and extremities, rarely with a Darier’s sign.

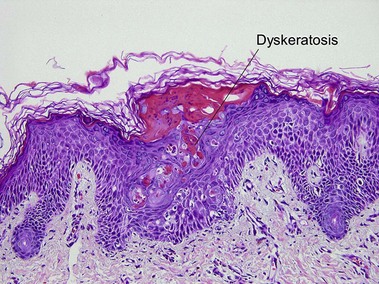

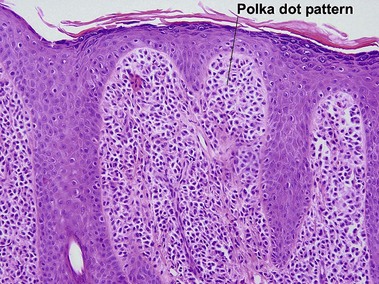

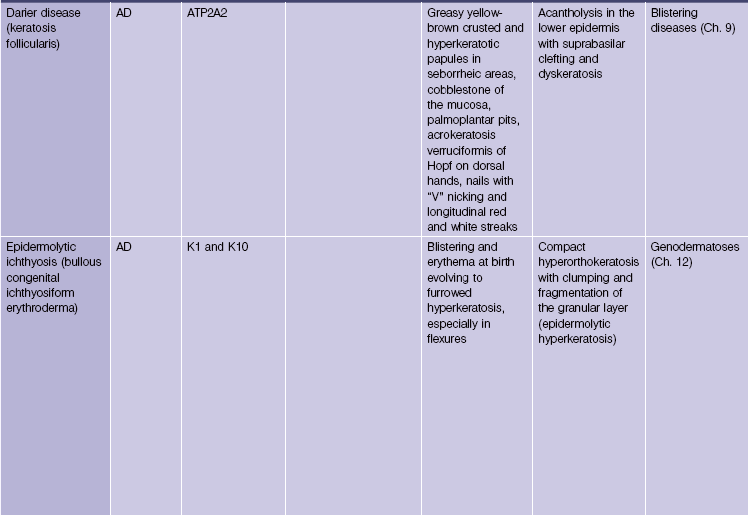

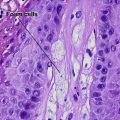

Epidermolytic ichthyosis (bullous congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma)

Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis is a histologic pattern that can be seen in several clinical settings, including palmoplantar keratoderma, solitary epidermolytic acanthoma, and epidermolytic ichthyosis. Not uncommonly, epidermolytic hyperkeratosis is an incidental finding in biopsies of another lesion such as a dysplastic nevus.

Bolognia, JL, Braverman, I. Pseudoxanthoma-elasticum-like skin changes induced by penicillamine. Dermatology. 1992; 184(1):12–18.

Davis, MD, Dinneen, AM, Landa, N, et al. Grover’s disease: clinicopathologic review of 72 cases. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999; 74(3):229–234.

Eng, AM, Bryant, J. Clinical pathologic observations in pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Int J Dermatol. 1975; 14(8):586–605.

Lebwohl, M, Phelps, RG, Yannuzzi, L, et al. Diagnosis of pseudoxanthoma elasticum by scar biopsy in patients without characteristic skin lesions. N Engl J Med. 1987; 317(6):347–350.

Meyrick Thomas, RH, Kirby, JD. Elastosis perforans serpiginosa and pseudoxanthoma elasticum-like skin change due to D-penicillamine. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1985; 10(4):386–391.

Shukla, SA, Veerappan, R, Whittimore, JS, et al. Mast cell ultrastructure and staining in tissue. Methods Mol Biol. 2006; 315:63–76.

Sybert, VP, Dale, BA, Holbrook, KA. Ichthyosis vulgaris: identification of a defect in synthesis of filaggrin correlated with an absence of keratohyaline granules. J Invest Dermatol. 1985; 84(3):191–194.