Genitalia

Inguinoscrotal disorders

Embryology

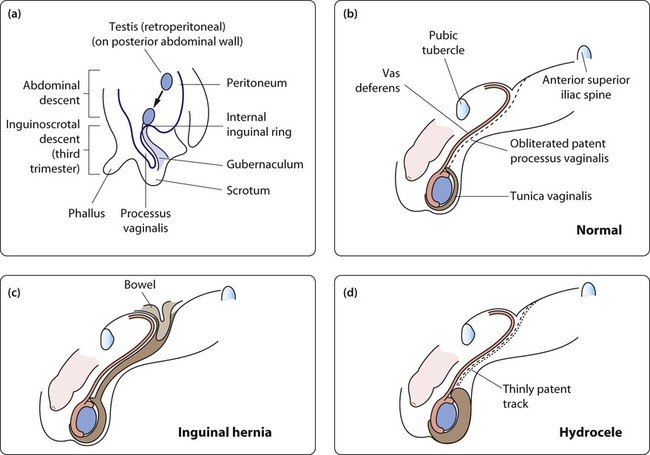

The testis is formed from the urogenital ridge on the posterior abdominal wall close to the developing kidney. Gonadal induction to form a testis is regulated by genes on the Y chromosome. During gestation, the testis migrates down towards the inguinal canal, guided by mesenchymal tissue known as the gubernaculum, probably under the influence of anti-Müllerian hormone (Fig. 19.1a).

Inguinoscrotal descent of the testis requires the release of testosterone from the fetal testis. A tongue of peritoneum, the processus vaginalis, precedes the migrating testis through the inguinal canal. This peritoneal extension normally becomes obliterated after birth, but failure of this process may lead to the development of an inguinal hernia or hydrocele (Fig. 19.1b–d).

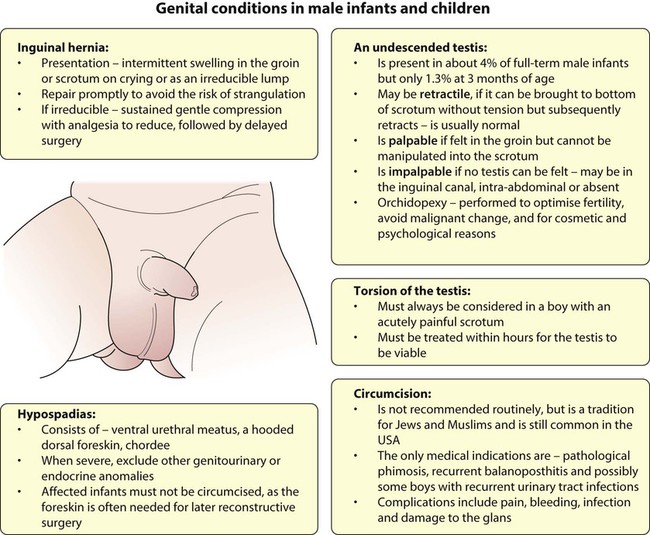

Inguinal hernia

Inguinal hernias usually present as an intermittent swelling in the groin or scrotum on crying or straining. Unless the hernia is observed as an inguinal swelling (Figs 19.2, 19.3), diagnosis relies on the history and the identification of thickening of the spermatic cord (or round ligament in girls). The groin swelling may become visible on raising the intra-abdominal pressure by gently pressing on the abdomen or asking the child to cough.

Hydrocele

A patent processus vaginalis, which is sufficiently narrow to prevent the formation of an inguinal hernia, may still allow peritoneal fluid to track down around the testis to form a hydrocele (Fig. 19.4). Hydroceles are asymptomatic scrotal swellings, often bilateral, and sometimes with a bluish discoloration. They may be tense or lax but are non-tender and transilluminate. Some hydroceles are not evident at birth but present in early childhood after a viral or gastrointestinal illness. The majority resolve spontaneously as the processus continues to obliterate, but surgery is considered if it persists beyond 18–24 months of age. A hydrocele of the cord forms a non-tender mobile swelling in the spermatic cord.

Undescended testis

An undescended testis has been arrested along its normal pathway of descent (Fig. 19.5). At birth, about 4% of full-term male infants will have a unilateral or bilateral undescended testis (cryptorchidism). It is more common in preterm infants because testicular descent through the inguinal canal occurs in the third trimester. Testicular descent may continue during early infancy and by 3 months of age the overall rate of cryptorchidism in boys is 1.5%, with little change thereafter. Contrary to previous teaching, it is now recognised that occasionally a testis which is fully descended at birth can ascend to an inguinal position during childhood, accounting for some late-presenting ‘undescended’ or ‘ascended’ testes. This phenomenon may be due to a relative shortening of cord structures during growth of the child.

Investigations

Useful investigations include:

• Ultrasound – this has a limited role in identifying testes in the inguinal canal in obese boys but cannot reliably distinguish between an intra-abdominal or absent testis. It is performed in children with bilateral impalpable testes to verify internal pelvic organs.

• Hormonal – for bilateral impalpable testes, the presence of testicular tissue can be confirmed by recording a rise in serum testosterone in response to intramuscular injections of human chorionic gonadotrophin (HCG); these boys may require specialist endocrine review.

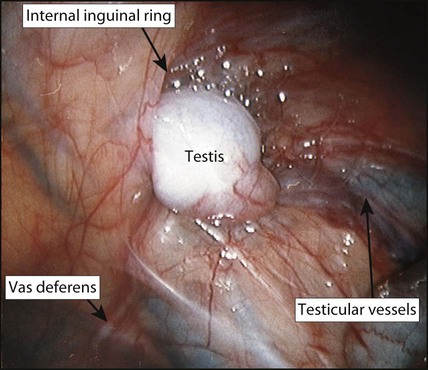

• Laparoscopy (Fig. 19.6) – the investigation of choice for the impalpable testis. Under anaesthesia, inguinal examination is first carried out to check that the testis is not in the inguinal canal.

Management

Surgical placement of the testis in the scrotum (orchidopexy) is undertaken for several reasons:

• Fertility – to optimise spermatogenesis, the testis needs to be in the scrotum below body temperature. The timing of orchidopexy is controversial, but orchidopexy during the second year of life may optimise reproductive potential. After 6 months of age descent of testis is unlikely and referral for paediatric surgical review at that age is recommended. Fertility after orchidopexy for a unilateral undescended testis is close to normal. In contrast, fertility is reduced to around 50% after bilateral orchidopexy for palpable undescended testes, and men with a history of bilaterally impalpable testes are usually sterile.

• Malignancy – undescended testes have histological abnormalities and an increased risk of malignancy. The risk is greater for bilateral undescended testes and the greatest risk is for testes which are intra-abdominal. Although the evidence is somewhat contradictory, some studies have suggested that early orchidopexy for a unilateral undescended testis reduces the risk to nearly the same as a normal testis. A scrotal testis can also be more easily self-examined than an inguinal or ectopic one.

• Cosmetic and psychological – if a testis is absent, a prosthesis can be used but this is best delayed until a larger adult-sized prosthesis can be inserted.

The acute scrotum

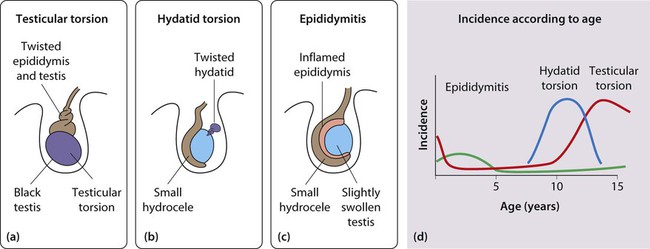

Torsion of the testis

Testicular torsion is most common in adolescents but may occur at any age, including the perinatal period (Fig. 19.7). The pain is not always centred on the scrotum but may be in the groin or lower abdomen. Atypical presentation is not unusual and the testes must always be examined whenever a boy or young man presents with inguinal or lower abdominal pain of sudden onset (see Case History 19.1). There may be a history of previous self-limiting episodes. Torsion of the testis must be relieved within 6–12 h of the onset of symptoms for there to be a good chance of testicular viability. Surgical exploration is mandatory unless torsion can be excluded. If torsion is confirmed, fixation of the contralateral testis is essential because there may be an anatomical predisposition to torsion, for example the ‘bell clapper’ testis, where the testis is not anchored properly. An undescended testis is at increased risk of torsion and at increased risk of delayed diagnosis. It may also be confused with an incarcerated hernia. Expert Doppler ultrasound looking at flow in the testicular blood vessels may allow torsion of the testis to be differentiated from epididymitis, but should not be used to diagnose torsion as only early surgical correction may salvage the testis. If there is any doubt about the cause of a painful scrotum, surgery should be performed.

Abnormalities of the penis

Hypospadias

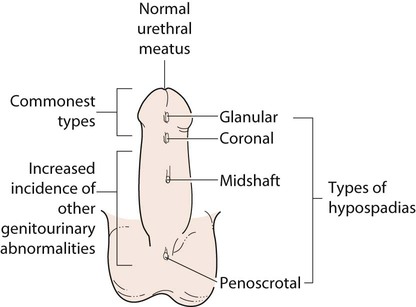

In the male fetus, urethral tubularisation occurs in a proximal to distal direction under the influence of fetal testosterone. Failure to complete this process leaves the urethral opening proximal to the normal meatus on the glans and this is termed hypospadias (Fig. 19.10). This is a common congenital anomaly, affecting about 1 in every 200 boys. Recent studies suggest that the incidence is increasing.

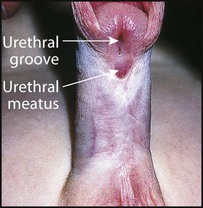

• A ventral urethral meatus – in most cases the urethra opens on or adjacent to the glans penis, but in severe cases the opening may be on the penile shaft or in the perineum (Fig. 19.11)

• A hooded dorsal foreskin – the foreskin has failed to fuse ventrally

• Chordee – a ventral curvature of the shaft of the penis, most apparent on erection. This is only marked in the more severe forms of hypospadias (Fig. 19.12).

Circumcision

There are only a few medical indications for circumcision:

• Phimosis (Fig. 19.13). This term is often used to describe the inability to retract the foreskin. As described above, at birth the foreskin is non-retractile and phimosis is physiological. Pathological phimosis is seen as a whitish scarring of the foreskin and is rare before the age of 5 years. The condition is due to a localised skin disease known as balanitis xerotica obliterans (BXO), which also involves the glans penis and can cause urethral meatal stenosis

• Recurrent balanoposthitis (Fig. 19.14). Single attack of redness and inflammation of the foreskin, sometimes with a purulent discharge, is common and usually responds rapidly to warm baths and a broad-spectrum antibiotic. Recurrent attacks of balanoposthitis (inflammation of the glans and foreskin) are uncommon and circumcision is occasionally indicated.

• Recurrent urinary tract infections. Although urinary infection is more common in uncircumcised boys the overall incidence is low and routine circumcision is not justified as a preventative measure. However, circumcision may be helpful in reducing the risk of urinary tract bacterial colonisation in boys with upper urinary tract anomalies complicated by recurrent urinary infection. It may also be appropriate in boys with spina bifida who need to perform clean intermittent urethral catheterisation.

Genital disorders in girls

Vulvovaginitis/vaginal discharge

Vulvovaginitis and vaginal discharge are common in young girls. They may result from infection (bacterial or fungal), specific irritants, poor hygiene or sexual abuse, although none of these factors is present in most cases. Vulvovaginitis may rarely be associated with threadworm infestation. Parents should be advised about hygiene, the avoidance of bubble bath and scented soaps and the use of loose-fitting cotton underwear. Swabs should be taken to identify any pathogens, which can then be specifically treated. Salt baths may be helpful. Oestrogen cream applied sparingly to the vulva may relieve the problem in resistant cases by increasing vaginal resistance to infection as prepubertal tissues tend to be atrophic. If there are any concerns about sexual abuse, the child must be seen by a paediatrician (see Ch. 7). Rarely, if the vaginal discharge is persistent or purulent, examination under anaesthesia may be needed to exclude a vaginal foreign body or unusual infections.

Disorders of sexual differentiation are considered in Chapter 11.