CHAPTER 17 Genetic Counseling

Any couple that has had a child with a serious abnormality must inevitably reflect on why this happened and whether any child(ren) they choose to have in future might be similarly affected. Similarly, individuals with a family history of a serious disorder are likely to be concerned that they could either develop the disorder or transmit it to future generations. They are also very concerned about the risk that their normal children might transmit the condition to their offspring. For all those affected by a genetic condition that is serious to them, great sensitivity is needed in communication. Just a few words spoken with genuine caring concern can put patients at ease and allow a meaningful session to proceed; just a few careless words that make light of a serious situation can damage communication irrevocably. The importance of confidence and trust in the relationship between patient and health professional must never be underestimated. In the commercial world the same applies—confidence is a prerequisite for business contracts (between both parties).

Definition

It is also agreed that genetic counseling should include a strong communicative and supportive element, so that those who seek information are able to reach their own fully informed decisions without undue pressure or stress (Box 17.1).

Establishing the Diagnosis

Even when a firm diagnosis has been made, problems can arise if the disorder in question shows etiological heterogeneity. Common examples include hearing loss and non-specific mental retardation, both of which can be caused by either environmental or genetic factors. In these situations empirical risks can be used (p. 346), although these are not as satisfactory as risks based on a precise and specific diagnosis.

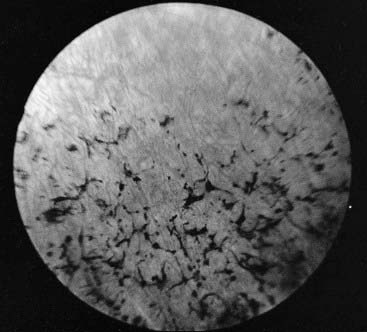

A disorder is said to show genetic heterogeneity if it can be caused by more than one genetic mechanism (p. 346). Many such disorders are recognized, and counseling can be extremely difficult if the heterogeneity extends to different modes of inheritance. Commonly encountered examples include the various forms of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (Figure 17.1), Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (p. 296), and retinitis pigmentosa, all of which can show autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, and X-linked recessive inheritance (Table 17.1). Fortunately, progress in molecular genetics is providing solutions to many of these problems. For example, mutations in the gene that codes for rhodopsin, a retinal pigment protein, are found in approximately 30% of families showing autosomal dominant inheritance of retinitis pigmentosa (Figure 17.2) and the molecular basis of the most common forms of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (type 1), also known as hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy, is now understood (p. 296).

Table 17.1 Hereditary Disorders that can Show Different Patterns of Inheritance

| Disorder | Inheritance Patterns |

|---|---|

| Cerebellar ataxia | AD, AR |

| Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease | AD, AR, XR |

| Congenital cataract | AD, AR, XR |

| Ehlers-Danlos syndrome | AD, AR, XR |

| Ichthyosis | AD, AR, XR |

| Microcephaly | AD, AR |

| Polycystic kidney disease | AD, AR |

| Retinitis pigmentosa | AD, AR, XR, M |

| Sensorineural hearing loss | AD, AR, XR, M |

AD, Autosomal dominant; AR, autosomal recessive; XR, X-linked recessive; M, mitochondrial.

Calculating and Presenting the Risk

In some counseling situations, calculation of the recurrence risk is relatively straightforward and requires little more than a reasonable knowledge of mendelian inheritance. However, many factors, such as delayed age of onset, reduced penetrance, and the use of linked DNA markers, can result in the calculation becoming much more complex. The theoretical aspects of risk calculation are considered in more detail in Chapter 22.

Quantification—The Numerical Value of a Risk

Most prospective parents will be familiar to some degree with the concept of risk, but not everyone is comfortable with probability theory and the alternative ways of expressing risk, such as in the form of odds or as a percentage. Thus, for example, a risk of 1 in 4 can be presented as an odds ratio of 3 to 1 against, or numerically as 25%. Consistency and clarity are important if confusion is to be avoided. It is also essential to emphasize that a risk applies to each pregnancy and that chance does not have a memory. For example, that parents have just had a child with an autosomal recessive disorder (recurrence risk of 1 in 4) does not mean that their next three children will be unaffected. A useful analogy is that of the tossed coin that cannot be expected to remember whether it landed heads or tails at the last throw and cannot therefore be expected to know what it should do at the next throw.

Discussing the Options

Having established the diagnosis and discussed the risk of occurrence/recurrence, the counselor is then obliged to ensure that the consultands are provided with all of the information necessary for them to make their own informed decisions. This should include details of all the choices open to them. For example, if relevant, the availability of prenatal diagnosis should be discussed, together with details of the techniques, limitations and risks associated with the various methods employed (see Chapter 21). Mention will sometimes be made of other reproductive options. These can include alternative approaches to conception, such as artificial insemination using donor sperm, the use of donor ova and preimplantation genetic diagnosis (p. 335). These techniques can be used when one partner is infertile, as in the case of Klinefelter syndrome and Turner syndrome (see Chapter 18), or simply to bypass the possibility that one or other partner will transmit his or her disadvantageous gene(s) to the baby.

Communication and Support

Despite all of these measures, a counseling session can be so intense and intimidating that the amount and accuracy of information retained can be very limited. For this reason, a letter summarizing the topics discussed at a counseling session is usually sent to the family afterwards. In addition, they are sometimes contacted later by a member of the counseling team, thereby providing an opportunity for clarification of any confusing issues and for further questions to be answered.

It is poor practice to simply convey information of a distressing nature without offering an opportunity for further discussion and long-term support. Most genetic counseling centers maintain informal contact with relevant families through a network of genetic nurse counselors who are familiar with the family and their particular circumstances. This is especially valuable for prospective parents who subsequently request specific prenatal diagnostic investigations, and for presymptomatic adults who are shown to be at high risk of developing late-onset autosomal dominant disorders such as Alzheimer disease (p. 342) and Huntington disease (p. 293). Genetic registers (p. 332) provide a useful means of ensuring that effective contact can be maintained with all such relevant family members.

Outcomes in Genetic Counseling

In practice the three main outcome measures that have been assessed are recall, impact on subsequent reproductive behavior, and patient satisfaction. Most studies have shown that the majority of individuals who have attended a genetic counseling clinic have a reasonable recall of the information given, particularly if this was reinforced by a personal letter or follow-up visit. Nevertheless, confusion can arise, and as many as 30% of counselees have difficulty in remembering a precise risk figure. Studies that have focused on the subsequent reproductive behavior of couples that have attended a genetic counseling clinic have shown that approximately 50% have been influenced to some extent. The factors that have been shown to be influential are the severity of the disorder, the desire of the parents to have children, and whether prenatal diagnosis and/or treatment are available. Finally, studies that have attempted to assess patient satisfaction have struggled to address the problem of how this should best be defined. For example, an individual could be very satisfied with the way in which they were counseled but remain very dissatisfied by lack of a precise diagnosis or the availability of subsequent prenatal diagnostic tests.

Special Problems in Genetic Counseling

There are a number of special problems that can arise in genetic counseling.

Consanguinity

A consanguineous relationship is one between blood relatives who have at least one common ancestor no more remote than a great-great-grandparent. Consanguineous marriage is widespread in many parts of the world (Table 17.2). In Arab populations, the most common type of consanguineous marriage occurs between first cousins who are the children of two brothers, whereas in the Indian subcontinent uncle–niece marriages are the most commonly encountered form of consanguineous relationship. Although there is in these communities some recognition of the potential disadvantageous genetic effects of consanguinity, there is also a strongly held view that these are greatly outweighed by social advantages such as greater family support and marital stability.

| Country | Incidence (%) |

|---|---|

| Kuwait | 54 |

| Saudi Arabia | 54 |

| Jordan | 50 |

| Pakistan | 40–50 |

| India | 5–60 |

| Syria | 33 |

| Egypt | 28 |

| Lebanon | 25 |

| Algeria | 23 |

| Japan | 2–4 |

| France, UK, USA | 2 |

Data adapted from various sources including Jaber L, Halpern GJ, Shohat M 1998 The impact of consanguinity worldwide. Commun Genet 1:12–17.

Many studies have shown that among the offspring of consanguineous marriages, there is an increased incidence of both congenital malformations and other conditions that will present later, such as hearing loss and mental retardation. For the offspring of first cousins, the incidence of congenital malformations is increased to approximately twice that seen in the offspring of unrelated parents. Almost all of this increase in morbidity and mortality is attributed to homozygosity for autosomal recessive disorders, a finding consistent with Garrod’s original observation that ‘the mating of first cousins gives exactly the conditions most likely to enable a rare, and usually recessive, character to show itself’ (p. 113).

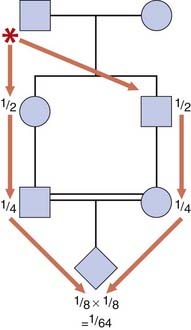

Therefore, for first cousins, the probability that their first child will be homozygous for their common grandfather’s deleterious gene will be 1 in 64 (Figure 17.3). Similarly, the risk that this child will be homozygous for the common grandmother’s recessive gene will also be 1 in 64. This gives a total probability that the child will be homozygous for one of the grandparent’s deleterious genes of 1 in 32. This risk should be added to the general population risk of 1 in 40 that any baby will have a major congenital abnormality (p. 249), to give an overall risk of approximately 1 in 20 that a child born to first-cousin parents will be either malformed or handicapped in some way. Risks arising from consanguinity for more distant relatives are much lower.

For consanguineous marriages, there is also a slightly increased risk that a child will have a multifactorial disorder. In practice this risk is usually very small. In contrast, a close family history of an autosomal recessive disorder can convey a relatively high risk that a consanguineous couple will have an affected child. For example, if the sibling of someone with an autosomal recessive disorder marries a first cousin, the risk that their first baby will be affected equals 1 in 24 (p. 342).

Incest

Incestuous relationships are those that occur between first-degree relatives—in other words, brother-sister or parent-child (Table 17.3). Marriage between first-degree relatives is forbidden, both on religious grounds and by legislation, in almost every culture. Incestuous relationships are associated with a very high risk of abnormality in offspring, with less than half the children of such unions being entirely healthy (Table 17.4).

Table 17.3 Genetic Relationship between Relatives and Risk of Abnormality in their Offspring

| Genetic Relationship | Proportion of Shared Genes | Risk of Abnormality in Offspring (%) |

|---|---|---|

| First degree | 1/2 | 50 |

| Parent–child Brother–sister |

||

| Second degree | 1/4 | 5–10 |

| Uncle–niece Aunt–nephew Double first cousins |

||

| Third degree | 1/8 | 3–5 |

| First cousins |

Table 17.4 Frequency of the Three Main Types of Abnormality in the Children of Incestuous Relationships

| Abnormality | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Intellectual impairment | |

| Severe | 25 |

| Mild | 35 |

| Autosomal recessive disorder | 10–15 |

| Congenital malformation | 10 |

Adoption and Genetic Disorders

The physician with a knowledge of genetics can also be called on to try to determine whether a child who is being placed for adoption will develop a genetic disorder. For the offspring of consanguineous or incestuous matings, risks can be given as outlined previously (see Tables 17.3 and 17.4). Adoption societies sometimes also wish to place a child with a known family history of a particular hereditary disorder. This raises the difficult ethical dilemma of predictive testing in childhood for conditions showing onset in adult life (p. 365). Increasingly it is felt that such testing should not be undertaken unless this will be of direct medical benefit to the child. In practice, even when a child is actually affected by a genetic disorder, suitable adoptive parents can usually be found.

Disputed Paternity

This presents a difficult problem for which the help of a clinical geneticist is sometimes sought. Until recently paternity could never be proved with absolute certainty, although it could be disproved or excluded in two ways. If a child was found to possess a blood group or other polymorphism not present in either the mother or the putative father, then paternity could be confidently excluded. For example, if the mother and putative father both lacked blood group B, but this was present in the child, the putative father could be excluded. Similarly, if a child lacked a marker that the putative father would have had to transmit to all of his children, then once again paternity could be excluded. As an example, a putative father with blood group AB could not have a child with blood group O.

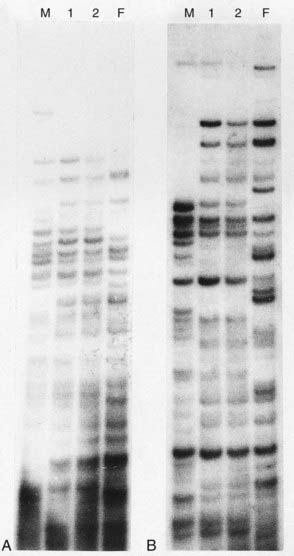

The limitations of these approaches have been overcome by the development of genetic fingerprinting using minisatellite repeat sequence probes (pp. 17, 69) and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) (p. 67). The pattern of DNA fragments generated by these probes, and SNP variants, is so highly polymorphic that the restriction map obtained is unique to each individual, with the exception of identical twins (Figure 17.4). If DNA from the child and the mother is analyzed, then the bands inherited from the biological father can be analyzed and compared with those present in DNA from the putative father(s). If these match, this gives an extremely high mathematical probability that the putative and biological fathers are the same individual.

ASHG/ACMG: Statement. Genetic testing in adoption. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66:761-767.

Clarke A, editor. Genetic counselling. Practice and principles. London: Routledge, 1994.

Clarke A, Parsons E, Williams A. Outcomes and process in genetic counseling. Clin Genet. 1996;50:462-469.

A critical review of previous studies of the outcomes of genetic counseling.

Frets PG, Niermeijer MF. Reproductive planning after genetic counselling: a perspective from the last decade. Clin Genet. 1990;38:295-306.

Harper PS. Practical genetic counseling, 5th ed. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1998.

An extremely useful practical guide to all aspects of genetic counseling.

Jaber L, Halpern GJ, Shohat M. The impact of consanguinity worldwide. Community Genet. 1998;1:12-17.

A review of the incidence and consequences of consanguinity in various parts of the world.

Jeffreys AJ, Brookfield JFY, Semeonoff R. Positive identification of an immigration test-case using human DNA fingerprints. Nature. 1985;317:818-819.

Turnpenny P, editor. Secrets in the genes: adoption, inheritance and genetic disease. London: British Agencies for Adoption and Fostering, 1995.

A multi-author basic text covering aspects of genetics relevant to the adoption process.

Elements