CHAPTER 8 General and Regional Anesthesia and Postoperative Pain Control

INTRODUCTION

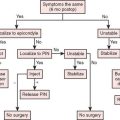

Orthopaedic procedures for the elbow are well suited to regional anesthetic techniques. Continuous catheter techniques provide postoperative analgesia and allow early limb mobilization. In addition to intraoperative anesthesia, brachial plexus and peripheral nerve blocks may also be used in the treatment and prevention of reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Conversely, although the benefits of regional anesthesia in this patient population are well established, the operative site may be adjacent to neural structures, as with total elbow arthroplasty or supracondylar fractures. For example, ulnar nerve dysfunction may occur in up to 10% of patients undergoing elbow arthroplasty.17 Early diagnosis and intervention are paramount in reducing the severity of nerve injury; assessment of neurologic function would not be possible in the presence of a regional block. Thus, the anesthetic and analgesic management are based on the patient’s evolving neurologic status (including the need for serial neurologic examinations, the anticipated rehabilitative goals, and history of side effects or interactions to systemic analgesics). Meticulous regional anesthetic technique, careful patient positioning, and serial postoperative neurologic examinations are required to reduce the incidence of neurologic dysfunction while optimizing surgical outcome.

INTRAOPERATIVE ANESTHETIC MANAGEMENT

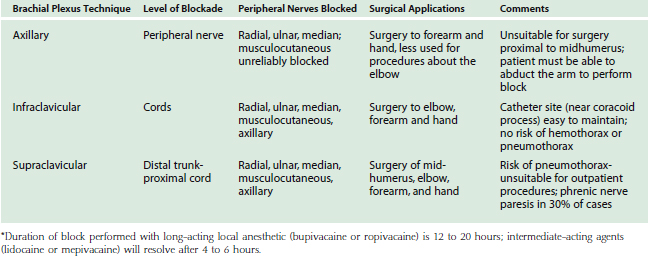

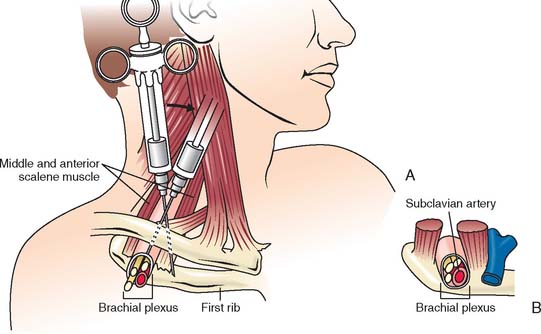

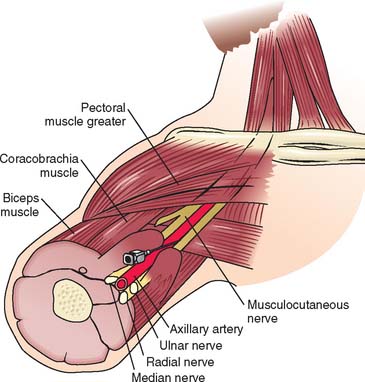

Surgical procedures for the distal humerus, elbow, and proximal radius, and ulna are commonly performed with regional anesthetic techniques.4 The brachial plexus may be blocked using four distinct approaches. Advances in needles, catheters, and nerve stimulator technology have facilitated the localization of neural structures and improved success rates. Selection of regional technique is dependent on the surgical site (Table 8-1). For surgery on the elbow, the supraclavicular (Fig. 8-1), infraclavicular, or axillary (Fig. 8-2) approaches are ideal because these approaches provide adequate blockade of the lower trunk, which remains unblocked with the more proximal interscalene technique. Supraclavicular, infraclavicular, and axillary approaches to the brachial plexus are reliable and provide consistent anesthesia to the four major nerves of the brachial plexus: median, ulnar, radial, and musculocutaneous.19 However, the small but definite risk of pneumothorax associated with supraclavicular blocks makes this approach unsuitable for outpatient procedures. Typically, pneumothorax occurs 6 to 12 hours after hospital discharge; therefore, a postoperative chest radiograph is not helpful. Although chest tube placement is advised for pneumothorax greater than 20% of lung volume, the lung may also be re-expanded with a small Teflon catheter under fluoroscopic guidance, eliminating the need for hospital admission. The infraclavicular and axillary approaches to the brachial plexus eliminate the risk of pneumothorax and reliably provide adequate anesthesia for surgery near the elbow.14,19 The infraclavicular approach has the added advantage of not requiring abduction during regional block, which would be painful in the presence of arm/forearm fracture.6 The various approaches to the brachial plexus blockade may be performed before surgical incision or after postoperative upper extremity neurologic function has been determined.

Although preoperative brachial plexus block reduces the intraoperative requirement of volatile anesthetic and opioids, and in theory provides pre-emptive analgesia, postoperative evaluation of neurologic function is not possible until block resolution. In addition, few outcome studies exist comparing regional and general anesthesia specifically for surgery about the elbow. However extrapolating the results of forearm and hand procedures under single-injection brachial plexus block versus general anesthesia, a regional technique is associated with improved analgesia, reduced opioid consumption and postoperative nausea and vomiting, and early hospital dismissal.15 Overall, there are early but no long-term benefits with a single-injection regional anesthetic technique compared with a general anesthetic. However, placement of an indwelling perineural catheter results in more substantial and lasting benefits, including avoidance of hospital admission/readmission, decreased opioid-related side effects and sleep disturbance, and improved rehabilitation.11,13,20 Thus, anesthetic management of patients undergoing elbow surgery is focused on postoperative analgesia, rather than intraoperative anesthesia to improve perioperative outcomes.

POSTOPERATIVE ANALGESIA

Patients undergoing major upper extremity surgery experience substantial postoperative pain. Indeed, 30% of patients undergoing ambulatory hand and elbow surgery reported moderate to severe pain at 24 hours postoperatively.16 Failure to provide adequate analgesia impedes early physical therapy and rapid rehabilitation, which are important for maintaining joint range of motion, facilitating hospital dismissal and preventing readmission. Traditionally, postoperative analgesia following major upper extremity surgery was provided by intravenous patient-controlled analgesia (PCA). However, opioids do not consistently provide adequate pain relief and often cause sedation, constipation, nausea/vomiting, and pruritus. Recently, clinical series have consistently reported that continuous brachial plexus block provided a superior quality of analgesia and surgical outcomes compared with systemic opioids but with fewer side effects.4,11 These reports suggest that continuous peripheral techniques may be the optimal analgesic method following elbow surgery. Appreciation of the indications, benefits, and side effects associated with both conventional and novel analgesic approaches is paramount to maximizing rehabilitative efforts and improving patient satisfaction.

MULTIMODAL ANALGESIA AND PERIPHERAL BLOCKADE

Multimodal analgesia is a multidisciplinary approach to pain management, with the aim of maximizing the positive aspects of the treatment while limiting the associated side effects. Because many of the negative side effects of analgesic therapy are opioid related (and dose dependent), limiting perioperative opioid use is a major principle of multimodal analgesia. Not surprisingly, the efficacy and side effects of analgesic therapy are major determinants of patient satisfaction. In a prospective survey of 10,811 patients, after adjusting for patient and surgical factors, moderate or severe post-operative pain and severe nausea and vomiting were associated with patient dissatisfaction.18 The use of single-injection and continuous brachial plexus techniques and a combination of opioid and nonopioid analgesic agents for breakthrough pain results in superior pain control, attenuation of the stress response, and decreases opioid requirements.

CONVENTIONAL ANALGESIC METHODS

Parenteral Opioid Analgesics

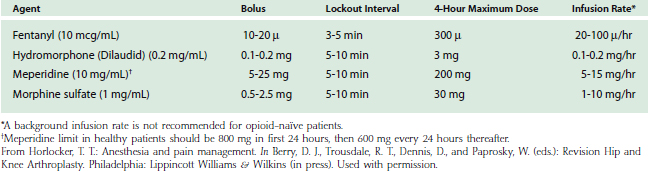

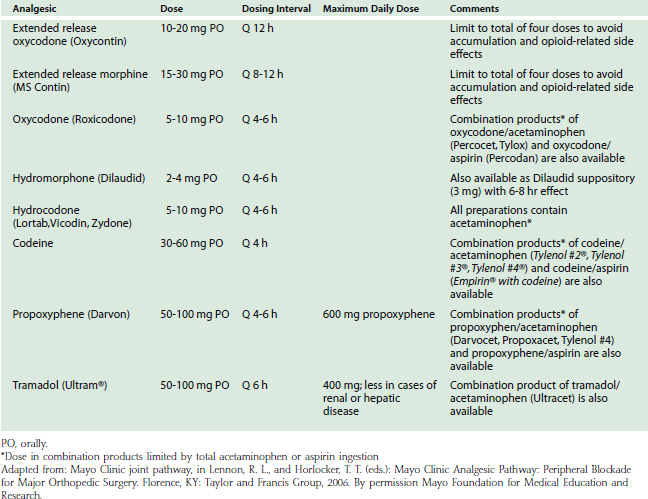

When adequate analgesia is achieved with systemic opioids, side effects, including sedation, nausea, and pruritus, are common. However, despite these well-defined side effects, opioid analgesics remain widely used for postoperative pain relief. Systemic opioids may be administered by intravenous, intramuscular, and oral routes. Current analgesic regimens typically employ intravenous PCA for 24 to 48 hours postoperatively, with subsequent conversion to oral agents. The PCA device may be programmed for several variables including bolus dose, lockout interval, and background infusion. The optimal bolus dose is determined by the relative potency of the opioid; insufficient dosing results in inadequate analgesia, whereas excessive dosing increases the potential for side effects, including respiratory depression. Likewise, the lockout interval is based on the onset of analgesic effects; too short of a lockout interval allows the patient to self-administer additional medication before achieving the full analgesic effect (and may result in accumulation/overdose of the opioid). A prolonged lockout interval will not allow adequate analgesia. The optimal bolus dose and lockout interval are not known, but ranges have been determined (Table 8-2). Varying the settings within these ranges appears to have little effect on analgesia or side effects. Although most PCA devices allow the addition of a background infusion, routine use in adult opioid-naïve patients is not recommended. There may be a role for a background opioid infusion in opioid-tolerant patients, however. Owing to the variation in patient pain tolerance, PCA dosing regimens may need to be adjusted in order to maximize the benefits and minimize the incidence of side effects. Despite the ease of administration and titratability, parenteral opioids may not provide adequate analgesia for major upper extremity surgery, particularly with movement, as evidenced by pain scores in the moderate to severe range in the first 2 days postoperatively.16

The adverse effects of opioid administration can cause serious complications in patients undergoing major orthopedic procedures. In a systematic review, Wheeler et al25 reported gastrointestinal side effects (nausea, vomiting, ileus) in 37%, cognitive effects (somnolence and dizziness) in 34%, pruritus in 15%, urinary retention in 16%, and respiratory depression in 2% of patients receiving PCA opioid analgesia.

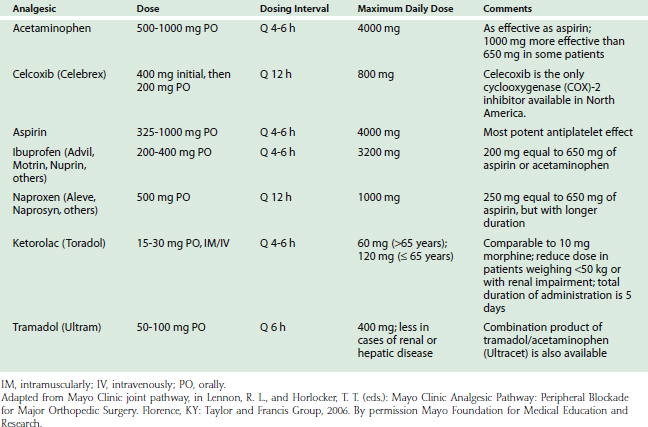

Nonopioid Analgesics

The addition of nonopioid analgesics reduces opioid use, improves analgesia, and decreases opioid-related side effects (Table 8-3). The multimodal effect is maximized through selection of analgesics that have complementary sites of action. For example, acetaminophen acts predominantly centrally, whereas other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) exert their effects peripherally.

Acetaminophen

The mechanism of analgesic action of acetaminophen has not been fully determined. Acetaminophen may act predominantly by inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis in the central nervous system. Acetaminophen has very few adverse side effects and is an important addition to the multimodal postoperative pain regimen, although the total daily dose must be limited to less than 4000 mg. The administration should be scheduled (not just on an as-needed basis) to maximize the pharmacologic effects. It is also important to note that many oral analgesics are an opioid-acetaminophen combination (Table 8-4). In these preparations, the total dose of opioid will be restricted to the acetaminophen ingested.

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs

The introduction of selective COX-2 inhibitors represented a breakthrough in perioperative pain management. Because they do not interfere with the coagulation system COX-2 inhibitors may be continued until the time of surgery and also may be administered in the immediate postoperative period. The perioperative administration of rofecoxib has been shown to have a significant opioid-sparing effect after major orthopedic surgery with no significant increase in perioperative bleeding.22,23 However, despite their efficacy, two (rofecoxib [Vioxx, Merck & Co., Whitehouse Station, NJ], valdecoxib [Bextra, Searle, Skokie, IL]) of three COX-2 inhibitors were voluntarily removed from general use because of an increased relative risk for confirmed cardiovascular events, such as heart attack and stroke, after 18 months of treatment.

The major side effects limiting NSAID use for postoperative pain control (renal failure, platelet dysfunction, and gastric ulcers or bleeding) are related to the nonspecific inhibition of the COX-1 enzyme.24 Advantages of the COX-2 inhibitors are the lack of platelet inhibition and a decreased incidence of gastrointestinal effects. All NSAIDs have the potential to cause serious renal impairment. Inhibition of the COX enzyme may have only minor effects in the healthy kidney, but unfortunately can lead to serious side effects in elderly patients or those with a low-volume condition (blood loss, dehydration, cirrhosis, or heart failure). Therefore, NSAIDs should be used cautiously in patients with underlying renal dysfunction, specifically in the setting of volume depletion due to blood loss.24 The effect of NSAIDs on bone formation and healing is of concern in the orthopedic patient population. Although the data are conflicting, there is evidence from animal studies that COX-2 inhibitors may inhibit bone healing.7 Thus, the adverse effects of COX-2 inhibitors must be weighed against the benefits. Until definitive human trials are performed, it is reasonable to be cautious with the use of NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors, especially when bone healing is critical. To date, however, there is no evidence that COX-2 inhibitors have a clinically important effect on bone ingrowth.

Oral Opioids

Oral opioids (see Table 8-4) are available in immediate-release and controlled-release formulations. Although immediate-release oral opioids are effective in relieving moderate to severe pain, they must be administered as often as every 4 hours. When these medications are prescribed “as needed” (prn), there may be a delay in the administration and a subsequent increase in pain. Furthermore, interruption of the dosing schedule, particularly during the night, may lead to an increase in the patient’s pain. The Acute Pain Management Guidelines developed by the Agency for Healthcare Policy and Research1 recommend a fixed dosing schedule for all patients requiring opioid medications for more than 48 hours postoperatively. The adverse effects of oral opioid administration are considerably less compared with that of intravenous administration, and are mainly gastrointestinal in nature.25

A controlled-release formulation of oxycodone (OxyContin, Purdue Pharma, Norwalk, CT) is also available and has been shown to provide therapeutic opioid concentrations and sustained pain relief over an extended time period. Administration of controlled-release oxycodone for 72 hours postoperatively improves analgesia and is associated with less sedation, vomiting, and sleep disturbances when compared with oxycodone given on either a fixed-dose or an as-needed basis.21 Therefore, a multimodal analgesic approach may include scheduled administration of controlled-release oxycodone combined with prn oxycodone for breakthrough pain to maximize the analgesic effect and decrease the associated side effects.

CONTINUOUS BRACHIAL PLEXUS ANALGESIA

As previously discussed, although single-injection brachial plexus techniques have been used, the duration of effect is often not sufficient to result in substantial improvements in analgesia or outcome.15 Recent applications of peripheral nerve block techniques have allowed prolonged postoperative analgesia (with an indwelling catheter) to assist rehabilitation and facilitate hospital dismissal.3,20 In addition, moderately severe upper extremity procedures, including total elbow arthroplasty, may be performed on an outpatient basis when analgesia is provided with an indwelling brachial plexus catheter.11,13 In all applications, the addition of a continuous brachial plexus catheter results in superior analgesia with fewer side effects than conventional systemic analgesic therapy.4,11

Brachial plexus catheters may be inserted using supraclavicular, infraclavicular, and axillary approaches. Although analgesia is produced in all nerve distributions, the block may not provide satisfactory surgical anesthesia, even with administration of more potent local anesthetic solutions. Therefore, continuous brachial plexus block is more often used to provide postoperative analgesia rather than intraoperative anesthesia. Catheters may be left indwelling for 4 to 7 days without adverse effects.10 A continuous infusion of local anesthetic solution, such as bupivacaine 0.125%, prevents vasospasm and increases circulation after limb/digit replantation or vascular repair. More concentrated solutions (0.2% ropivacaine or bupivacaine) result in complete sensory block and allow early joint mobilization after painful surgical procedures to the elbow.20 Local anesthetic selection is based on the duration and degree of sensory or motor block desired.3,12,20 Because analgesic requirements vary with activity, a basal infusion with intermittent on-demand boluses allows greater flexibility.12 The presence of dense sensory or motor block is not a contraindication to hospital dismissal. However, the patient should be informed of the anticipated duration of analgesia during the preoperative visit and instructed to protect the blocked extremity until block resolution (Box 8-1).

BOX 8-1 Instructions for At-Home Brachial Plexus Catheter Patients

Neurologic dysfunction and intravascular injection are the primary concerns associated with peripheral blockade. However, in a large series involving more than 50,000 peripheral blocks, there were six seizures and 12 patients who reported postoperative nerve injury. Most neurologic complications were transient.2 A series of nearly 4000 peripheral blocks, including 1650 axillary blocks, 69 patients (1.7%) developed transient neurologic dysfunction.5 Complete recovery occurred in 4 to 12 weeks in all patients but one, who required 25 weeks. Despite the placement of a continuous catheter and extended exposure to local anesthetics, neurologic complications following indwelling brachial plexus catheters are uncommon, with the frequency similar to that of single-injection techniques.3 Finally, the performance of a regional technique in a patient with a pre-existing neurologic condition remains controversial. Although the data are sparse, several retrospective series suggestthat these patients are not at a significantly increased risk of neurologic complications.8,9

INTRA-ARTICULAR CATHETERS

Intra-articular injection of local anesthetics is a well-established method of providing short-term analgesia in patients undergoing ambulatory procedures. Often near-complete pain relief is achieved for 4 to 6 hours, at which time the local anesthetic effect resolves and systemic analgesics are required. Recently, the introduction of disposable elastomeric and programmable pumps (Fig. 8-3) has allowed extended infusion (2 to 4 days) of local anesthetic.10 Because an intra-articular infusion does not provide complete blockade of the brachial plexus (compared with a neural sheath catheter), analgesia is often incomplete and oral opioids are required, although consumption is reduced. Note that all patients with infusions of local anesthetic solutions must be educated as to the signs and symptoms of local anesthetic toxicity and given instruction on how and when to call their physician for assistance (see Box 8-1).

1 Acute Pain Management Guideline Panel. Acute pain management: operative or medical procedures and trauma-clinical practice guideline. AHCPR Pub No 92-0032. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Public Health Service, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1992, p. 15.

2 Auroy Y., Benhamou D., Bargues L., Ecoffey C., Falissard B., Mercier F.J., Bouaziz H., Samii K. Major complications of regional anesthesia in France: the SOS regional anesthesia hotline service. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:1274.

3 Bergman B.D., Hebl J.R., Kent J., Horlocker T.T. Neurologic complications of 405 continuous axillary catheters. Anesth. Analg.. 2003;96:247.

4 Brown A.R. Anaesthesia for procedures of the hand and elbow. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol.. 2002;16:227.

5 Fanelli G., Casati A., Garancini P., Torri G. Nerve stimulator and multiple injection technique for upper and lower limb blockade: Failure rate, patient acceptance, and neurologic complications. Study Group on Regional Anesthesia. Anesth. Analg.. 1999;88:847.

6 Fuzier R., Fuzier V., Albert N., Decramer I., Samii K., Olivier M. The infraclavicular block is a useful technique for emergency upper extremity analgesia. Can. J. Anaesth.. 2004;51:191.

7 Gajraj N.M. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors. Anesth. Analg.. 2003;96:1720.

8 Hebl J.R., Horlocker T.T., Sorenson E.J., Schroeder D.R. Regional anesthesia does not increase the risk of postoperative neuropathy in patients undergoing ulnar nerve transposition. Anesth. Analg.. 2001;93:1606.

9 Hebl J.R., Kopp S.L., Schroeder D.R., Horlocker T.T. Neurologic complications after neuraxial anesthesia or analgesia in patients with preexisting peripheral sensorimotor neuropathy or diabetic polyneuropathy. Anesth. Analg.. 2006;103:1294.

10 Ilfeld B.M., Enneking F.K. A portable mechanical pump providing over four days of patient-controlled analgesia by perineural infusion at home. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med.. 2002;27:100.

11 Ilfeld B.M., Morey T.E., Enneking F.K. Continuous infraclavicular brachial plexus block for postoperative pain control at home: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:1297.

12 Ilfeld B.M., Morey T.E., Enneking F.K. Infraclavicular perineural local anesthetic infusion: a comparison of three dosing regimens for postoperative analgesia. Anesthesiology. 2004;100:395.

13 Ilfeld B.M., Wright T.W., Enneking F.K., Vandenborne K. Total elbow arthroplasty as an outpatient procedure using a continuous infraclavicular nerve block at home: A prospective case report. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med.. 2006;31:172.

14 Koscielniak-Nielsen Z.J., Rotboll N.P., Risby M.C. A comparison of coracoid and axillary approaches to the brachial plexus. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand.. 2000;44:274.

15 McCartney C.J., Brull R., Chan V.W., Katz J., Abbas S., Graham B., Nova H., Rawson R., Anastakis D.J., von Schroeder H. Early but no long-term benefit of regional compared with general anesthesia for ambulatory hand surgery. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:461.

16 McGrath B., Elgendy H., Chung F., Kamming D., Curti B., King S. Thirty percent of patients have moderate to severe pain 24 hr after ambulatory surgery: a survey of 5,703 patients. Can. J. Anaesth.. 2004;51:886.

17 Morrey B.F., Bryan R.S. Complications of total elbow arthroplasty. Clin. Orthop.. 1982;170:204.

18 Myles P.S., Williams D.L., Hendrata M., Anderson H., Weeks A.M. Patient satisfaction after anaesthesia and surgery: results of a prospective survey of 10,811 patients. Br. J. Anaesth.. 2000;84:6.

19 Neal J.M., Hebl J.R., Gerancher J.C., Hogan Q.H. Brachial plexus anesthesia: essentials of our current understanding. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med.. 2002;27:402.

20 ODriscoll S.W., Giori N.J. Continuous passive motion (CPM): theory and principles of clinical application. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev.. 2000;37:179.

21 Reuben S.S., Connelly N.R., Maciolek H. Postoperative analgesia with controlled-release oxycodone for outpatient anterior cruciate ligament surgery. Anesth. Analg.. 1999;88:1286.

22 Reuben S.S., Connelly N.R. Postoperative analgesic effects of celecoxib or rofecoxib after spinal fusion surgery. Anesth. Analg.. 2000;91:1221.

23 Reuben S.S., Fingeroth R., Krushell R., Maciolek H. Evaluation of the safety and efficacy of the perioperative administration of rofecoxib for total knee arthroplasty. J. Arthroplasty. 2002;17:26.

24 Stephens J.M., Pashos C.L., Haider S., Wong J.M. Making progress in the management of postoperative pain: a review of the cyclooxygenase 2-specific inhibitors. Pharmacotherapy. 2004;24:1714.

25 Wheeler M., Oderda G.M., Ashburn M.A., Lipman A.G. Adverse events associated with postoperative opioid analgesia: a systematic review. J. Pain. 2002;3:159.