Chapter 5 Gene Therapy and Emerging Molecular Therapies

| Abbreviations | |

|---|---|

| ADA | Adenosine deaminase |

| cDNA | Complementary DNA |

| CF | Cystic fibrosis |

| CFTR | Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| HS-TK | Herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase |

| mRNA | Messenger RNA |

| RISC | RNA-induced silencing complex |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| RNAi | RNA interference |

| siRNA | Short interfering RNA |

Advances in understanding molecular mechanisms of disease and manipulating genetic material, protein receptors, and antibodies provide new approaches for treatment of human diseases. Emerging therapeutic reagents include not only novel antibody and protein therapies, but also nucleic acid-based molecules, including complete genes, deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), complementary DNA (cDNA), ribonucleic acid (RNA), and oligonucleotides. Together with cell therapies and targeted approaches for protein and nucleic acid delivery, these reagents and strategies for administration are conceptualized within the broad borders of gene therapy and the emerging field of molecular medicine. Gene therapy was originally conceived as a treatment for monogenic (Mendelian) disease by complementation of a mutant gene with a normal (wild type) gene. However, gene therapy also includes treatment of acquired human disease by delivery of DNA encoding a therapeutic protein, or introducing a fragment of nucleic acid to interrupt the messenger RNA (mRNA) of a pathogenic protein. A key component of the use of nucleic acids is the spectrum of strategies used to focus therapies on specific organs, deliver genes to specific cells, or both. Targeting is achieved through genetically engineered viruses, receptor-ligand interactions, and antibodies. Therefore these gene-based reagents and the vehicles used to deliver them represent a novel form of “gene as drug.” This chapter presents a discussion of these molecular therapies.

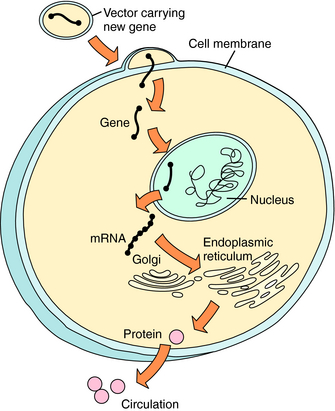

Basic concepts of gene transfer and gene expression are similar, regardless of the vehicle used to carry genetic material to the target cell (Fig. 5-1). After administration of the DNA-vector, the vehicle carrying DNA enters the cell by passing through the cell membrane or by active uptake via a specific receptor. The DNA is taken into the nucleus, where it can be processed. The host cell supplies enzymes necessary for transcription of the DNA into messenger RNA (mRNA) and translation of the mRNA into protein within the cytoplasm. The protein functions intracellularly or extracellularly to replace a hereditary deficient or defective protein, or to provide a therapeutic function. The protein may: (1) function intracellularly, such as adenosine deaminase (ADA) used to correct the mutation in lymphocytes responsible for one form of the severe combined immunodeficiency disease (SCID) syndrome; (2) replace a cell membrane protein, such as the cystic fibrosis (CF) transmembrane conductance regulator chloride channel (CFTR) mutant in CF; or (3) introduce a secreted protein, such as factor VIII, which is deficient in hemophilia. Successful gene transfer (also called transfection) and expression are evaluated by measuring RNA, protein, and, importantly, function in the target cell. In contrast to traditional pharmacological approaches, the goal of this therapy is alteration of the genotype of the cell, rather than alteration of the functional phenotype only.

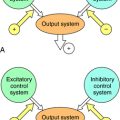

Nucleic acids can also be delivered into the cell to interrupt specific mRNA translation and subsequent protein production. The two general classes of nucleic acids, using independent mechanisms to silence genes through binding and triggering destruction of targeted mRNA, are antisense and RNA interference (RNAi) (Fig. 5-2). Antisense oligonucleotides are 12 to 28 nucleotide, single-strand sequences that are chemically modified to enhance their t1/2. Binding of these oligonucleotides to a complementary mRNA sequence results in cleavage of the targeted mRNA by endogenous RNaseH, an endoribonuclease that specifically recognizes RNA-DNA heteroduplexes. The cleaved mRNA and oligonucleotide are degraded, and protein translation is reduced. However, a high abundance of oligonucleotides is required for efficient antisense silencing. Larger oligonucleotides can also be engineered as a ribozyme to bind and directly cleave mRNA, and then repeat this process without self degradation. More than 50 different antisense oligonucleotides and ribozymes are in clinical trials, primarily directed toward oncogenic genes and infectious virus RNAs.

A recently developed mRNA silencing system is RNAi that takes advantage of endogenous RNA regulatory pathways (see Fig. 5-2). Large, double-stranded RNA sequences designed to target endogenous mRNA enter the cell and are cut into short interfering RNA (siRNA) by the dicer enzyme. Alternatively, synthetic siRNA may be delivered to the cell directly. In either case, the double-strand siRNA molecules are bound by a group of proteins called the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). The RISC proteins activate unwinding the siRNA to single-strand RNA that binds a specific mRNA molecule. The RISC cuts the mRNA in the region paired with the antisense siRNA sequence, and the cleaved mRNA is degraded to prevent protein translation. Clinical trials are in development using RNAi.

PRINCIPLES OF CLINICAL GENE THERAPY

Prerequisites for Human Gene Therapy

Application of gene transfer principles to gene therapy requires several critical considerations (Box 5-1). First, a candidate disease for gene therapy must be selected. Typically, this is a disease not successfully treated by currently available therapies. Second, the genetic basis of the disease must be determined by identifying the gene that encodes for a mutant protein or by locating the mutant gene using classical genetic studies. Third, the pathophysiology of the disease must be known so that the cellular site of normal and abnormal gene expression can be ascertained to target the therapy. A corollary is that the magnitude and duration of exogenous gene expression likely to ameliorate the disease should be estimated. Fourth, tools for detection of gene expression must be in hand, including methods for detection of RNA, protein, and protein function. Fifth, preclinical in vitro and in vivo systems for testing efficacy of gene transfer must be developed. This usually mandates that an animal model of disease be available. With few exceptions, these steps are developed in the laboratory before a strategy for clinical gene therapy is considered. Finally, pharmaceutical-grade nucleic acid or virus vector must be produced free of biological and chemical contaminants.

DNA and RNA Targeting and Delivery

Often, in vivo gene delivery is the only feasible strategy. Examples of in vivo targets for gene therapy include brain, lung, liver, muscle, blood vessels, and tumors. Intravenous injection of DNA and oligonucleotides can result in broad distribution to multiple tissues, with concentrations often highest in the liver and kidney. Thus, for efficient in vivo delivery, gene vectors are often directed to a cell population through sophisticated interventional techniques often used in clinical medicine. For example, in vivo transfer to a specific organ may be achieved through catheterization of that organ, by surgical approaches, or by fiberoptic-guided methods. Therefore specificity of cell targeting to achieve cell-specific gene expression also depends on the technical aspects of the in vivo delivery system.

DNA and vector-based methods used to introduce DNA or RNA into mammalian cells and the advantages and disadvantages of different systems are listed in Table 5-1. Therapeutic DNA transfected into cells by nonviral means is subcloned into a plasmid so that large quantities of plasmid DNA can be produced and purified. Plasmids can carry large pieces of DNA (more than 20 kb), thereby accommodating proteins with large coding sequences. Traditional methods for in vitro gene transfer are purified plasmid DNA delivered to cell lines by microinjection, coprecipitation of DNA with calcium phosphate, and transient electrical current to enhance permeability for DNA entry (electroporation). Although these techniques are often satisfactory experimentally, they generally result in DNA transfer to less than 1% of primary culture cells, are difficult to use in vivo, and have limited therapeutic use. More efficient vehicles have been developed for gene transfer, making in vivo gene delivery possible. Vehicles for DNA delivery include several plasmid- and virus-based vector systems. Plasmid-based vectors include plasmids mixed with liposomes and plasmids linked to ligand/receptor complexes, antibodies, or nanoparticles. Viral vectors are designed to use specific receptors and entry functions specific to particular cell types, using the host genome for transcription and translation. Viral vectors rarely use the wild-type virus but rather a genetically engineered virus that minimizes cytotoxicity and replication but retains the ability to enter and express a specific gene within the cell. The most widely studied vehicles for gene transfer are: (1) genetically engineered viruses that carry nucleic acid into cells; (2) liposomes mixed with DNA; and (3) DNA transferred alone by direct injection (“naked DNA”). The viral vectors commonly used in clinical trials include mouse Maloney retroviruses, adenoviruses, adeno-associated viruses, lentiviruses, herpes simplex virus, and vaccinia virus.

TABLE 5–1 Comparison of Commonly Used Vectors for Gene Transfer

| Vehicle | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Nonviral | ||

| Naked DNA | Ease of production | Low efficiency |

| No DNA size limitation | Transient expression | |

| Liposome-DNA | Ease of production | Low efficiency |

| No DNA size limitation | Transient expression | |

| Low immune reaction | ||

| Viral | ||

| Retrovirus | Ease of production | Transfer to dividing cells only |

| Efficient DNA transfer | Random DNA integration | |

| Stable expression | DNA transfer size limited | |

| Low immune reaction | ||

| Adenovirus | Ease of production | Host immune reaction |

| Efficient DNA transfer | Transient expression | |

| Transfer to nondividing cells | DNA transfer size limited | |

| Adeno-associated | Prolonged expression | Difficult production |

| Transfer to nondividing cells | Limited insert size | |

Liposomes are lipid molecular aggregates that bind to DNA, antisense oligonucleotides, or siRNA to facilitate cell entry (Fig. 5-3, A). Cell entry occurs by fusion with the cell membrane or by endocytosis. Liposome formulations have been developed containing monolayers, bilayers, or multilayers and possess charged (e.g., cationic lipids) or neutral surfaces. Transfection efficiency is variable, and the specific lipid type must be matched to that of the target cell to maximize gene transfer. Nucleic acid-lipid complexes have been combined with selected antibodies or receptor-specific ligands to further enhance cell targeting.

Recombinant retrovirus vectors are among the most widely used gene transfer vehicles. They have the advantage of integrating a therapeutic gene into the target cell genome. Production of a retrovirus vector that can carry nonviral (therapeutic) genes and is not capable of replication is a two-step process similar to that used to produce vectors from many different viruses (Fig. 5-3, B). First, a cell line containing the genes necessary for creating viral envelopes and viral replication must be created by transferring the retrovirus genes GAG, POL, and ENV to a cell. This “packaging” cell line does not contain the psi (ψ) sequence necessary for inserting the genes into the envelope and hence produces empty retrovirus “packages” that do not contain the therapeutic gene. Second, the packaging cell line is modified to contain other retrovirus sequences with a therapeutic gene (up to 9 kb in length) and a ψ encapsidation sequence, permitting the therapeutic gene (but not the GAG, POL, and ENV genes) to be inserted into the retrovirus envelope. This “producer” cell line creates and secretes viral particles containing the therapeutic gene that can enter a host cell, but, in the absence of GAG and POL, cannot replicate to make new virus. Thereby a replication-incompetent retrovirus is produced, collected from the cell media, and used in vitro or in vivo to deliver a gene to a target. After entering the target cell, integration of the therapeutic gene into the host genome is required for expression. Such integration is advantageous, if a sustained therapeutic effect is desired, but can only occur in dividing cells. Therefore this technique is particularly useful for ex vivo therapies. Retroviruses integrate DNA into the host genome randomly, potentially resulting in interruption of host DNA (insertional mutagenesis) or a silencing of transferred DNA expression.

Gene transfer vectors derived from adenoviruses have the major advantage of high-efficiency delivery to nondividing cells and high virus production, making them attractive for in vivo gene delivery. Adenovirus is a double-stranded DNA virus whose genome consists of early genes (E1 to E4), which code for regulatory proteins necessary for replication, and late genes (L1 to L5), which code for structural proteins. To produce an adenovirus vector for gene transfer (Fig. 5-3, C), the immediate early gene E1, responsible for replication but not infection, is deleted and replaced with the therapeutic gene (up to 7 kb). The E1 deficient therapeutic adenovirus grows only in cells expressing the E1 gene (serving much the same function as the retrovirus producer cells), generating adenoviruses used for gene transfer. Adenovirus infection occurs through a defined receptor and functions within the nucleus without integration into the host cell genome. Expression of the therapeutic DNA transferred by adenovirus vectors is transient (often <1 month). Although adenovirus vectors are highly efficient for transfer of genes to cells in vivo, some limitations prevent their more extensive use. Expression of viral proteins in infected cells can trigger a cellular immune response that results in adverse clinical symptoms, precluding long-term expression of the transferred gene and repeat administration. Because adenovirus results in transient expression, after initial immune sensitization, repeat dosing may result in even briefer expression as a result of immune destruction of vector-containing cells. Newer adenovirus vectors developed by removal of genes known to contribute to an immune response are currently under evaluation.

Adeno-associated and herpes simplex virus-based vectors have been approved for human use. Adeno-associated virus is a human single-stranded DNA parvovirus that integrates DNA into target cell genomes of cells not actively dividing. The adeno-associated virus vector system is similar to the retrovirus vector system, relying on a packaging cell line but also requiring wild-type adenovirus as a “helper” to complete viral production in vitro. Disadvantages of the adenovirus-associated vector system include a minimal size of the therapeutic gene that can be carried (<4.5 kb) and a low titer of virus particles produced. Lentivirus can be used to infect nonreplicating cells and can be produced in high titer. Herpes simplex-derived vectors can be used to enhance gene delivery to neurons.

Noguchi P. Risks and benefits of gene therapy. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:193-194.

Ratko TA, Cummings JP, Blebea J, Matuszewski KA. Clinical gene therapy for non-malignant disease. Am J Med. 2003;115:560-569.

Because this field is rapidly emerging, for the most up-to-date information on gene therapy clinical trials worldwide, see The Journal of Gene Medicine Clinical Trial web site at:

No Author, n.da http://www.wiley.co.uk/genetherapy/clinical.

Information on gene therapy clinical trials in the United States is at:

No Author, n.dc http://clinicaltrials.gov/search/term=gene+therapy.